Citation

Somerset v. Stewart, June 22, 1772, FULL TEXT via CommonLII

Excerpt

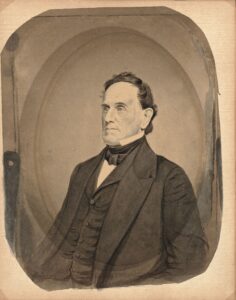

Lord Mansfield ruled in freedom seeker James Somerset’s favor (National Portrait Gallery, UK)

…The power of a master over his slave has been extremely different, in different countries. The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political; but only positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory : it’s so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.