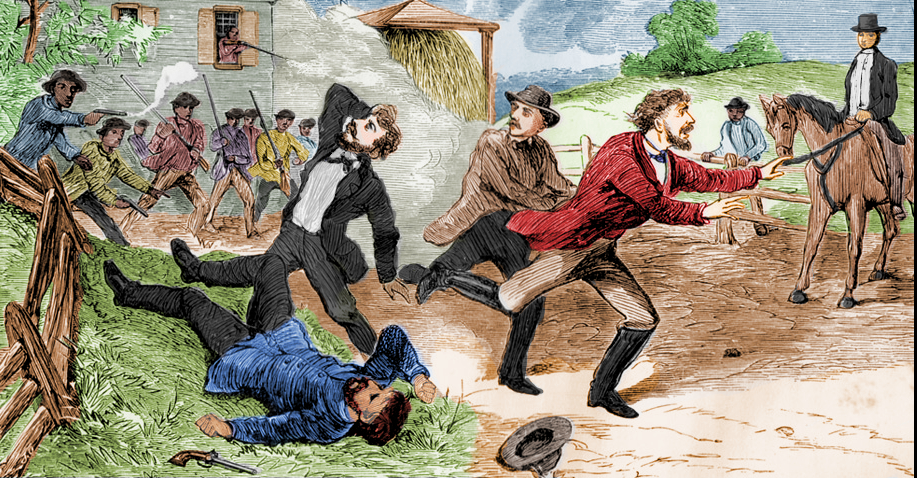

Banner image: Maryland freedom seekers and their Underground Railroad allies successfully resisted enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law at Christiana, Pennsylvania on the morning of September 11, 1851; original illustration by John Osler for William Still’s Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Gabe Pinsker (House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

- Listen to the author read a short excerpt from this essay

Finding the Gateway: Christiana, Pennsylvania

Driving through Lancaster County in Pennsylvania can sometimes feel like time traveling. US Route 30 offers a thoroughly twenty-first century experience, with SUVs and other automobiles darting past a cluttered roadside full of chain restaurants, strip malls, and motels. Things get quieter along Route 41, a multi-lane state road cutting through sprawling farms and warehouse complexes on the way toward the port of Baltimore. But just south of the small town of Christiana (population 1,165), if you venture onto the local roads, the nineteenth century suddenly emerges. One can even hear the clatter of horse-drawn buggies on winding country lanes. This is Amish country. But not too long ago, it was the ground zero of Black resistance to American slavery.

Right after a particularly sharp turn on Lower Valley Road, there is a state historical marker, perched on the edge of private farmland, which takes somber note of what it labels, “The Christiana Riot.” This sign commemorates the killing of a Maryland slaveholder on Thursday morning, September 11, 1851, by a group of enslaved freedom seekers and their allies who were desperately trying to stop a federal posse from enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law. “This incident did much to polarize the national debate over the slavery issue,” concludes the terse description. Probably no more than a couple dozen people pass by the sign each week.

Admittedly, no roadside marker could ever do justice to such a revolutionary act of resistance. The statement does not identify the four “runaways” while naming their enslaver, Edward Gorsuch, as the “Maryland farmer” who convinced federal agents to help him track down the fugitives. The text describes the site as “the Christiana home of William Parker, an African American who was giving them refuge,” without mentioning Eliza Parker, his wife, who was a co-organizer of this protective operation or that both of them had once been freedom seekers themselves. The marker also gets noticeably vague when narrating what happened next. “Neighbors gathered, fighting ensued, and Gorsuch was killed.” The phrase “Underground Railroad” does not appear. Nor does the marker spell out consequences for Black participants in this so-called “riot.” Yet the 1851 confrontation was a major victory for them and the larger antislavery movement. Today, it also represents a gateway for understanding the complex operations of the Underground Railroad and its struggle to destroy slavery in America.

Defining the Term: Underground Railroad

By the time of the resistance at Christiana, the phrase Underground Railroad was only about ten years old. It was metaphor born in the 1840s and popularized by abolitionist newspapers as part of a sweeping propaganda strategy designed to embarrass Southern enslavers. The point of the comparison was to highlight the growing traffic of enslaved people fleeing bondage. The metaphor also glorified the vast network of fugitive supporters who seemed more than willing to break state and federal laws to help liberate them.

Since those early days, however, the phrase has taken on wider meaning. For modern interpreters, the Underground Railroad can refer more broadly to the history of resistance against slavery whenever conducted through escape and flight. From this perspective, well before abolitionists employed the specific phrase in their newspapers, even as early as the colonial era, there were notable examples of an “underground railroad” that helped freedom seekers. Some interpreters then like to emphasize how this developing network to freedom expanded across the continent and continued through the Civil War until the abolition of chattel slavery in 1865.

One of the earliest public references to the “underground railroad” from the Albany Tocsin of Liberty in 1842, reprinted widely by other abolitionist newspapers that autumn (Chronicling America)

But whether the interpretive focus lies with the origins of the term or its evolving essence, popular misconceptions have abounded. People often take the memorable phrase too literally. Confused children sometimes visualize a type of subway train or metro moving runaway slaves under the ground. Grownups can also get stuck on the wording, depicting the Underground Railroad as a secret national organization with fixed leadership roles, such as stationmaster or conductor, operating regular escape routes which connected safe houses from the Deep South to Canada.

To be sure, there were heroic “conductors” and covert “stations” involved with quests for freedom, but the original metaphor was never intended as the centerpiece for an elaborate nationwide escape code. Frederick Douglass, who had fled from enslavement in Maryland in 1838, even worried about the disregard for secrecy among his underground allies. “I have never approved of the very public manner in which some of our western friends have conducted what they call the underground railroad,” he wrote in 1845, “but which I think, by their open declarations, has been made most emphatically the upperground railroad.”[1] Douglass’s warning to abolitionists in Ohio and elsewhere across the Old Northwest certainly highlights the movement’s decentralized nature. Various types of antislavery committees and communities worked on their own and in tandem to support freedom seekers. Yet despite occasional disagreements over tactics, these activists were always striving for what one leader shrewdly called, “practical abolition.”[2]

Freedom Seeking in Thematic Context

Understanding themes and context behind this historical Underground Railroad begins with an insight about how human networks functioned in an era of relatively weak central governments. Nineteenth-century freedom networks were never primarily about stations or safe houses, but always about people and the relationships which bound them together in common purpose.

Nineteenth-century freedom networks were never primarily about stations or safe houses, but always about people and the relationships which bound them together in common purpose.

Freedom seekers themselves were the initial element of this network to freedom, a “juggernaut of sinew and soul,” as Anthony Cohen puts it in the volume’s opening essay. Enslaved people had to risk leaving, not just bondage, but family, friends and quite literally, their known world. Relying mainly on testimony collected from ex-fugitives in Canada during the 1850s, Cohen explores what he considers the common “playbook” for those who succeeded in running away. This approach helps shed light on figures such Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond, the four young Black men who ran away from Maryland enslaver Gorsuch in 1849. They had been accused of theft, and fled to avoid punishment, but what propelled them onward to the Parker home in Christiana, surely came straight from a liberation playbook.[3]

But it’s also true that Christiana involved far more than freedom seeking. By crossing the Mason-Dixon Line, which separated Maryland from Pennsylvania, those American refugees stepped directly into a constitutional debate as old as the republic itself. In their revealing essays, Paul Finkelman and H. Robert Baker help explain the unique morass that American federalism had produced in relation to fugitive slaves. The problems began with a maddeningly vague constitutional clause, which the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 did little to rectify. Several Northern states then attempted to manipulate the ambiguities of federal law to assert habeas corpus rights for any accused Blacks, under the shield of state-based personal liberty statutes which they had written to protect their free Black residents from kidnapping. This states’ rights challenge ultimately provoked the Supreme Court’s Prigg v. Pennsylvania decision in 1842, but that sweeping verdict failed to end the federalism arguments. Southern states then responded with increasingly brutal slave stealing statutes of their own, punishing some defiant Northerners, like Underground Railroad operative Calvin Fairbank, with lengthy terms of imprisonment.[4]

No figure ever paid the kind of price at the federal level which Fairbank had paid in Kentucky (seventeen years total in prison) but these escalating legal battles resulted in a much tougher 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, which established real federal criminal penalties for aiding runaways, along with a host of draconian provisions included as part of the Compromise of 1850. That is another reason why Christiana mattered. The killing of Gorsuch –and the utter failure of federal prosecutors to secure any convictions in the shocking case only a year after passage of the controversial statute– marked the beginning of a new decade of sectional troubles. Federal agents did eventually claim to stabilize the nation’s broken fugitive rendition system, and Finkelman concedes they proved efficient at times, but throughout the 1850s, Southern enslavers never stopped complaining that their legal rights were being flouted by Northern judicial officers and juries.

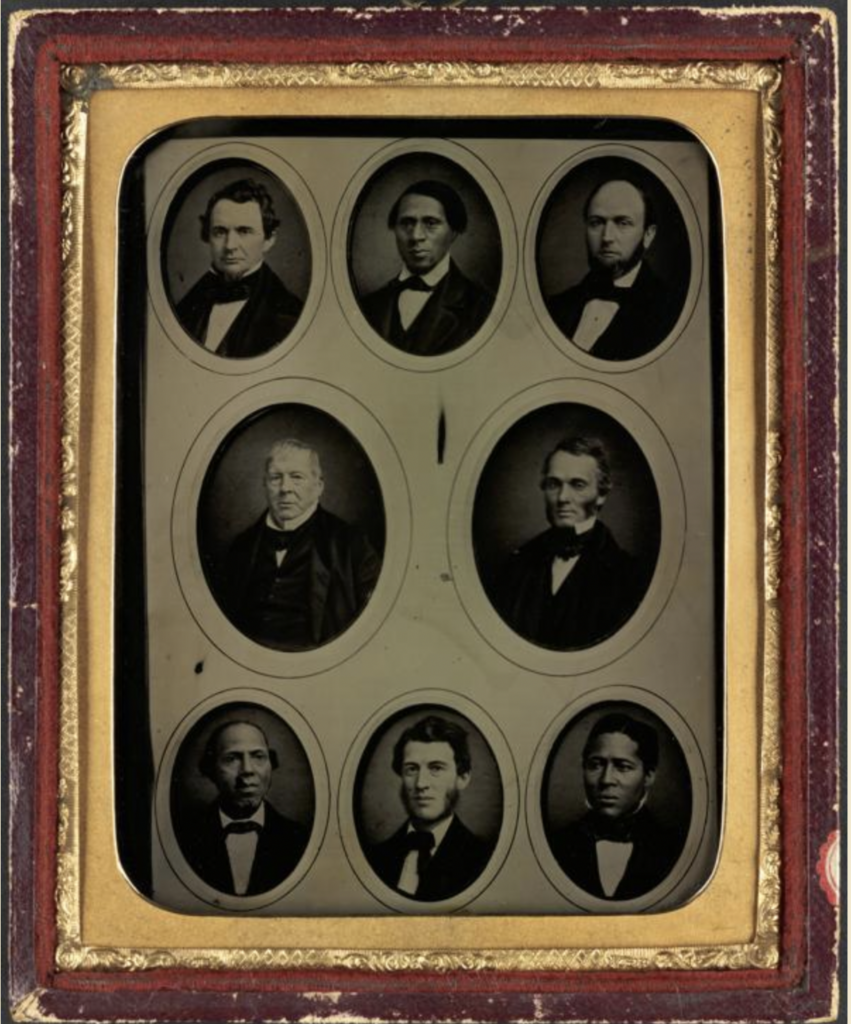

What truly exasperated pro-slavery forces, however, was the growing impunity of the Underground Railroad operating beyond the courthouses and hearing rooms. In their richly intertwined essays, Manisha Sinha, Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, and Kate Clifford Larson, describe how the nation’s multiplying fugitive cases intersected with the rise of various multi-racial antislavery communities, providing outlets for remarkable examples of Black leadership in an era when Northern racism was both out in the open and fully legal. Sinha details how Black-led vigilance committees sprang into action in cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia and elsewhere, ostensibly to guard against kidnapping but invariably working in partnership with Garrisonian antislavery societies, fiery abolitionist newspapers, and antislavery political parties to aid all types of Black freedom seekers. LaRoche explains how both white and Black churches in the North supported this organized resistance effort, noting the essential contributions of Black institutions, such as the Twelfth Baptist Church in Boston, led by Pastor Leonard Grimes, who had once been a convicted “slave stealer” in Virginia. Larson highlights special contributions from women, not only as Southern freedom seekers, but also as Northern vigilance operatives, illustrating why Harriet Tubman was such a remarkable figure, because she excelled in each dimension.

Philadelphia Vigilance Committee leaders during the 1850s; William Still in bottom right corner (Boston Public Library)

Vigilance was their watchword, and yet this common nineteenth-century term has been largely forgotten in popular depictions of the Underground Railroad. Before the rise of modern police forces and centralized governments, most Americans accepted citizen-organized vigilance committees as a legitimate method for fighting crime. For African Americans, their local vigilance committees embodied the absolute necessity for self-defense in an era of rampant slave catchers and kidnappers. They certainly provided inspiring examples of Black-led and multi-racial collective action. Fortunately for historians, vigilance organizers also proved adept as record-keepers. As all the essays here demonstrate, there are a multitude of ways to document Underground Railroad operations but none more revealing than antebellum vigilance journals, such as those kept by William Still in Philadelphia or Sydney Howard Gay in New York. They provide an irrefutable –and now fully digitized and accessible—body of evidence critical for studying slave escapes.[5]

Vigilance collectives went by different names but existed practically everywhere in the North, and not just in larger cities. William Parker, an escaped slave himself, spearheaded “an organization for mutual protection” among his Black neighbors in Lancaster County.[6] This rural vigilance group waged veritable war with kidnappers long before Gorsuch ever showed up with his federal posse in 1851. Testimony at the subsequent trial revealed that the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee knew all about their peers in Christiana and had even tipped them off to the impending confrontation with federal marshals. The organizational reach of this network was impressive. As the confrontation at Christiana escalated on the morning of September 11, Eliza Parker blew a horn to alert her more vigilant neighbors that they needed help. Dozens showed up for this supposed “riot” that in retrospect looks far more like a planned battle. Kellie Carter Jackson’s essay further dissects the meaning of this potent story by explaining how it illustrated the significance of Black revolutionary violence in the age of slavery.

Undated photograph showing William and Eliza Parker’s former home and site of the 1851 resistance. The stone structure fell into disrepair after the Civil War and got destroyed in the 1890s. (Moore’s Memorial Library, Christiana, PA)

After the Christiana shootout, additional elements of the network rushed in to perform more traditional underground tasks. The Parkers, the four Gorsuch runaways, and other key resistance figures fled separately with different types of assistance. None seemed to have been stopped or seriously chased along their escape routes to Canada. Parker even got help from the great Douglass, who had known him when they were enslaved in Maryland. Meanwhile, local allies scoured the site of the resistance, destroying evidence that had been left behind from other fugitive cases. The local police and US marines eventually rounded up dozens of “suspects,” and the federal government charged more than three dozen white and Black individuals with treason, not mere enticement or “riot,” to send a stern political message. Yet abolitionist newspapers characteristically rallied to their cause and antislavery groups raised funds for the legal defense. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens helped lead a team of respected attorneys for the federal trial held at Philadelphia in late 1851. The jury ended up acquitting the first accused traitor after only about 15 minutes of deliberations. Prosecutors then released the remaining defendants, to the enduring scorn of embittered white Southerners.[7]

James Oakes analyzes how this dramatic episode and others like it, such as the arrest and rendition of Anthony Burns from Boston in 1854, intensified the nation’s fractured sectional politics. The return of Burns to slavery was ostensibly a much-needed triumph for the law-and-order crowd, but Oakes illustrates how the heavy-handed federal response mainly served to antagonize Northern public opinion. The antislavery setback in that case was also purely temporary. Within a year, the ex-slave stealer Pastor Grimes and his Boston congregation had raised the funds necessary to purchase Burns’s freedom. In addition, 1854 marked the last time the federal government was able to execute a successful rendition hearing anywhere in New England. That was not so surprising. Very few Northern counties had active fugitive slave commissioners. During the entire decade, there were only about 125 formal rendition hearings held across the country, or about a dozen a year on average.[8] White southerners complained heatedly about this betrayal and kept escalating their demands for sectional justice. Oakes explains how these political threats then radicalized leading Republicans, including outwardly moderate figures like Abraham Lincoln, and set the stage for hardliners (on both sides) to prevail during the secession crisis in 1860-61.

The Civil War thus erupted in 1861 owing as much to the debate over fugitives as any other facet of the slavery controversy, but what Chandra Manning demonstrates in her perceptive essay was how wartime runaways, or “contrabands,” also had a significant impact on Union policy during the war. Manning discerns a veritable “alliance” emerging between the contrabands and the Union military, one that helped propel not only emancipation, but also the ultimate defeat of the Confederate military.

The ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in late 1865 marked the end of the Underground Railroad’s long campaign toward “practical abolition,” while also opening a new era of interpretative debate. Spencer Crew surveys a wide range of perspectives on the movement’s legacy and meaning, from participants to modern-day scholars. He highlights figures such as William Still, whose post-war memoir and publication of Philadelphia vigilance records, The Underground Railroad (1872), probably stands as the single most important primary source on the subject. But Crew also examines the contributions of academic pioneers such as Wilbur Siebert and revisionists such as Larry Gara.[9] The scholarly debate has been mostly about how to center the story –whether on white antislavery activists, freedom seekers themselves, or free Black vigilance operatives. Certainly, everyone involved deserves a place in the narrative, but as Fergus Bordewich suggests, over the years there has been something crippling to the popular mind about the enduring myths which emerged from the earliest academic studies. Too many people remain fixated on the supposedly secret ways that heroic white abolitionists tried to aid desperate Black runaways.

Freedom Seeking in Regional Context

Perhaps the most persistent of these Underground Railroad myths have been the ones grounded in real estate. Throughout the Ohio Valley and along the Mason-Dixon Line, there are still popular claims about old Quaker farms or other homesteads having once served as safe houses and now revealing their tales through rediscovered secret tunnels or hiding places. That is partly why the regional section of this volume opens in the West, to help shift the focus toward a more sophisticated understanding about what LaRoche has called “the geography of resistance.”

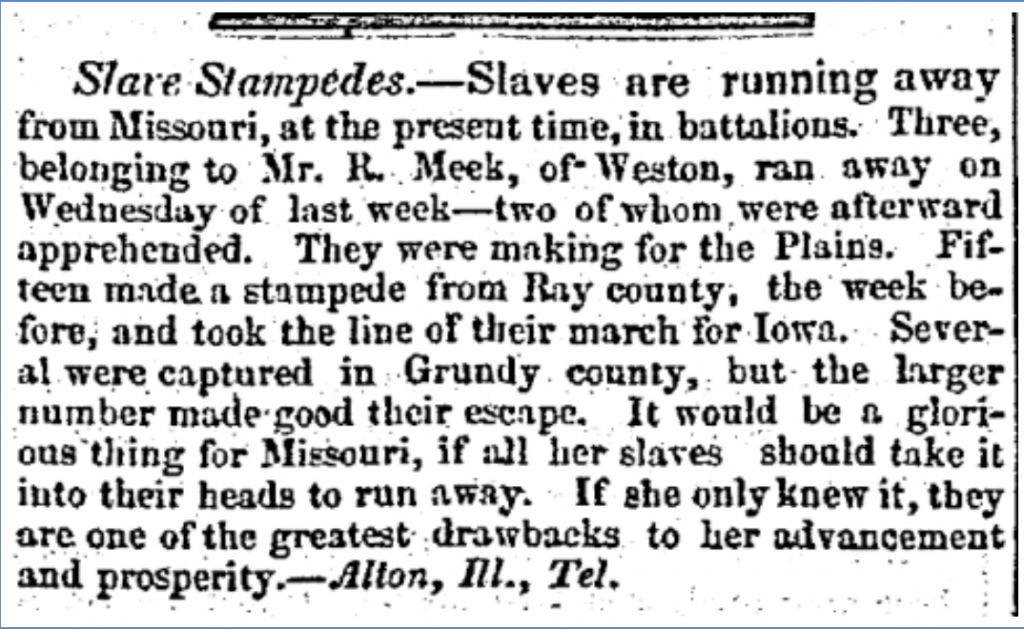

Déanda Johnson and Alice L. Baumgartner achieve this kind of sophistication in their vivid depictions of Underground Railroad activities across the northwestern and southwestern plains. Both describe freedom seekers confronting especially bewildering realities in the antebellum West, where the North Star was never the sole guidepost toward freedom and where the always-contested federalism issues gave way toward an even more confusing collision of common law doctrines, territorial codes, and international laws. The presence of Mexicans, Native Americans, free Blacks, and various white ethnic groups also created unparalleled cultural diversity, which combined with the notoriously weak hold of frontier governments, led to grave uncertainty about how or whether the formerly enslaved would be protected. Yet people still ran away, and not merely as individuals, but sometimes in large groups or “slave stampedes.” Across the western prairies and plains, there were also sporadic examples of collective action and violent resistance, not too dissimilar from the antebellum “border war” escalating back East.[10]

1853 Illinois newspaper report on “slave stampedes” from western Missouri “making for the Plains.” (The Liberator, June 10, 1853)

Damian Alan Pargas and Cassandra Newby-Alexander explain how a precarious “geography of freedom” developed within the American slave empire itself. Pargas details how marronage operated inside the South, allowing for freedom seekers to find occasional haven in urban areas, across wilderness or swamp regions, and among Native American communities. In terms of sheer numbers, Pargas argues that more freedom seekers probably took advantage of these marronage opportunities than those who benefited from the vigilance networks on Northern free soil. Newby-Alexander focuses on the waterways along the southeastern seaboard, documenting how coastal networks which had existed since the colonial era often worked to the advantage of antebellum freedom seekers. Moreover, this “saltwater railroad” ran in multiple directions, not only northward toward Eastern port cities, but also southward toward the Caribbean.

According to Robert H. Churchill, Stanley Harrold, and Eric Foner, there was an equally complex and often fraught experience along the Upper South borderlands. Their essays highlight what Churchill describes as the “pervasive violence” throughout the extended sectional border. White supremacists and pro-slavery forces lurked across regions such as the Ohio Valley or south central Pennsylvania. What resulted were frequent confrontations with vigilance networks, not necessarily as dramatic as the one at Christiana, but still ominous and occasionally violent. The enslaved themselves were also in motion along the borderlands more than elsewhere, sometimes bound in coffles for the domestic slave trade, but also occasionally seeking liberation in “stampedes.” Harrold describes some extraordinary episodes, like the failed insurrectionary flight of about 75 armed enslaved men from Maryland in 1845, or the 77 individuals, including numerous children, who got captured attempting to flee Washington, DC aboard a steamer called The Pearl a mere three years later. Foner emphasizes the importance of freedom seekers moving in groups as well, albeit usually in smaller family units. He details an intricate web of vigilance connections across the Atlantic borderland communities that made such daring escapes possible. Each essay further underscores the multi-racial nature of the borderland networks. Regardless of whether freedom seekers were fleeing or fighting, traveling alone or in battalions, there were clearly numerous Black and white operatives willing to risk their lives and careers to protect them.

The circumstances were somewhat different in New England and Canada, as both Kathryn Grover and Gordon Barker attest. In the Upper North, multi-racial coordination was probably just as prevalent among antislavery groups, but the specter of physical danger was far more distant. Grover provides numerous examples of fugitives living in the open across New England despite occasional rendition scares, such as with Burns in 1854. This was especially revealing, because even though abolitionists were influential in places such as Boston, they were still in the political minority across the region. Barker also details the evolution of Canada’s reputation as a safe haven for freedom seekers, describing the development of multiple connections between antislavery individuals and communities across the international border and through the Civil War.

Conclusion: Envisioning the Future

When the state historical commission first dedicated the Christiana roadside marker in 1998, they clearly considered what happened there to have been unusual. They were commemorating a rare act of violence, one that was difficult to explain in a few sentences and perhaps somewhat awkward to commemorate. It was an imperfect gesture, to be sure, but nonetheless an important byproduct of decades of hard work from local and academic historians.

A similar effort today might be more confident in its treatment of the subject’s multiple dimensions. That same year in 1998 Congress also adopted sweeping new legislation authorizing the National Park Service (NPS) to spearhead a “Network to Freedom” initiative, one designed to raise awareness about the significance of the Underground Railroad in American history. Subsequently, over the next twenty-five years, there has been a wholesale shift in how events such as the Christiana resistance have been interpreted. An outpouring of fresh scholarship and the launching of long-overdue preservation efforts have reshaped the commemorative landscape concerning American resistance to slavery. This latest handbook captures some of that interpretive energy through a collection of contributions from several of the key figures who helped engineer this new historical order.

What they have achieved is greater appreciation for the open defiance of the Underground Railroad and the complexity of human connections which sustained its evolving network. Modern scholarship has made clear that while an event like Christiana was unusual, it was also representative in certain profound ways. People should now recognize that running away from enslavement was always an act of resistance and getting caught was almost never the end of the freedom battle.

People should now recognize that running away from enslavement was always an act of resistance and getting caught was almost never the end of the freedom battle.

Yet there is still so much more to be done. The latest insights about the Underground Railroad are far more granular than ever before, but some of the certainties of the past are now missing. Some readers will wonder, for example, where are the hard estimates about numbers for annual runaways, or detailed maps of escape routes that once got featured in earlier studies? They are largely absent here, because as RJM Blackett so eloquently writes in his Epilogue, most of what scholars and interpreters have been doing lately is about “unspooling” the unique stories which they have documented, usually from an avalanche of recently digitized evidence. According to Blackett, historians must now reconnect these threads to help frame more universal insights regarding resistance motivations, relationships, and antislavery culture.

Sometimes it is hard for people to appreciate the slow pace of change for this type of interpretive quest. But again, returning to Christiana might help. At present, there is a roadside marker. But in another twenty-five years or so, who knows? There might be a reconstructed stone house at the resistance site, situated not too far from a brand new NPS visitor center, one displaying the documents from the original inquest and rare artifacts such as the still-extant tin horn which Eliza Parker once blew to rouse her vigilance network. There could be a multi-media wall streaming video interviews with descendants from the Parker and Gorsuch families, many of whom now live scattered across two countries. Park rangers might take dozens of eager students out on daily tours, not peering inside darkened tunnels to help envision the Underground Railroad, but instead surveying an actual battlefield. Only then would such time travelers really start to experience the full variety of hallowed grounds that once contributed so mightily to a new birth of freedom in America.

Local historians claim this was the horn that Eliza Parker used at Christiana in September 1851, preserved by the family which owned the farm. It has never been on regular public display. (Christiana Historical Society / Photo by Aiden Pinsker)

Discussion Questions

Christiana (1851), orig. by John Osler, colorized by Gabe Pinsker (House Divided Project)

- Why did the editors select this illustration of the 1851 resistance at Christiana as the cover image for the new NPS handbook on the Underground Railroad? How does it offer a gateway for a revised understanding about how freedom seekers helped to destroy American slavery?

- How has the definition of the phrase “Underground Railroad” evolved? Why do historians still debate the meaning of this metaphor?

- What changes when you start to think about the Underground Railroad as a network of people rather than a network of safe houses?

- Have you ever visited an Underground Railroad historic site? What was that experience like for you? How might visiting a “battlefield” such as Christiana alter people’s understanding about the history of the Underground Railroad?

Citations

[1] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), 101.

[2] David Ruggles quoted in Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015), 65.

[3] For the most detailed modern accounts of the entire Christiana episode, see Jonathan Katz, Resistance at Christiana: The Fugitive Slave Rebellion, Christiana, Pennsylvania, September 11, 1851: A Documentary Account (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1974), Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991) and Ella Forbes, But We Have No Country: The 1851 Christiana, Pennsylvania Resistance (Cherry Hill, NJ: Africana Homestead Legacy, 1998).

[4] See [Laura Smith Haviland, ed.], Rev. Calvin Fairbank During Slavery Times (Chicago: R.R. McCabe, 1890) and Randolph Paul Runyon, Delia Webster and the Underground Railroad (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996).

[5] The web companion for this handbook contains a directory of web links to digitized vigilance and other UGRR records, including special mapping resources created with materials generously provided from scholars such as William C. Kashatus and institutions such as Columbia University Library.

[6] [William Parker], “The Freedman’s Story,” Atlantic Monthly 17 (Feb – Mar 1866): 161.

[7] For key details on the local aftermath of September 11, 1851, see older accounts by David R. Forbes, A True Story of the Christiana Riot (Quarryville, PA: Sun Printing,1898) and W.U. Hensel, The Christiana Riot and the Treason Trials of 1851: An Historical Sketch, rev. ed., (Lancaster, PA: New Era, 1911).

[8] See Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970). Campbell identifies 332 individuals returned as fugitive slaves over the decade, but that includes cases without due process, also known as recaption in common law or kidnapping according to antislavery activists. For more detail on the operations of the federal rendition system, see Matthew Pinsker, “After 1850: Reassessing the Impact of the Fugitive Slave Act,” in D.A. Pargas, ed., Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America, 1775-1860 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018), 93-115.

[9] Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad: From Slavery to Freedom (New York: MacMillan, 1898). Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1961).

[10] Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Author Profile

MATTHEW PINSKER holds the Brian Pohanka Chair of Civil War History at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and serves as Director of the House Divided Project, an innovative effort to build digital resources on the Civil War era. Pinsker has previously held visiting fellowships at New America Foundation, US Army War College and the National Constitution Center. Pinsker directs the Slave Stampedes on the Southern Borderlands initiative in partnership with the National Park Service Network to Freedom. He is the author of two books on Abraham Lincoln and numerous articles on various topics in the Civil War Era, including on the Underground Railroad and resistance to slavery. Pinsker graduated from Harvard College and received a D.Phil. degree in Modern History from the University of Oxford. He often leads K-12 teacher-training workshops on the Underground Railroad for organizations such as the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Pinsker currently serves the Organization of American Historians (OAH) as a “Distinguished Lecturer” and sits on the advisory boards of several historic organizations, including Ford’s Theatre Society, Gettysburg Foundation, National Civil War Museum, President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home, and the Thaddeus Stevens-Lydia Hamilton Smith site in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

MATTHEW PINSKER holds the Brian Pohanka Chair of Civil War History at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and serves as Director of the House Divided Project, an innovative effort to build digital resources on the Civil War era. Pinsker has previously held visiting fellowships at New America Foundation, US Army War College and the National Constitution Center. Pinsker directs the Slave Stampedes on the Southern Borderlands initiative in partnership with the National Park Service Network to Freedom. He is the author of two books on Abraham Lincoln and numerous articles on various topics in the Civil War Era, including on the Underground Railroad and resistance to slavery. Pinsker graduated from Harvard College and received a D.Phil. degree in Modern History from the University of Oxford. He often leads K-12 teacher-training workshops on the Underground Railroad for organizations such as the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Pinsker currently serves the Organization of American Historians (OAH) as a “Distinguished Lecturer” and sits on the advisory boards of several historic organizations, including Ford’s Theatre Society, Gettysburg Foundation, National Civil War Museum, President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home, and the Thaddeus Stevens-Lydia Hamilton Smith site in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Additional online resources for Matthew Pinsker

- ESSAY: Vigilance in Pennsylvania (PHMC, 2000)

- ESSAY: William Still (Clarke Center, 2003)

- ESSAY: Underground Railroad & Coming of Civil War (GLI, 2010)

- ESSAY: Emancipation Moments (NTHP / USCRC, 2013)

- ESSAY: Interpreting the Upper-Ground Railroad (van Balgooy, ed., 2015)

- ESSAY: Did End of Civil War Mean End of Slavery? (Smithsonian, 2015)

- ESSAY: After 1850: Reassessing the Fugitive Slave Law (Pargas, ed., 2018)

- VIDEO: Underground Railroad Reconsidered (CUNY, 2014)

- VIDEO: Teaching Underground Railroad History (C-SPAN, 2017)

- WEBSITE: Slave Stampedes (House Divided / NPS)