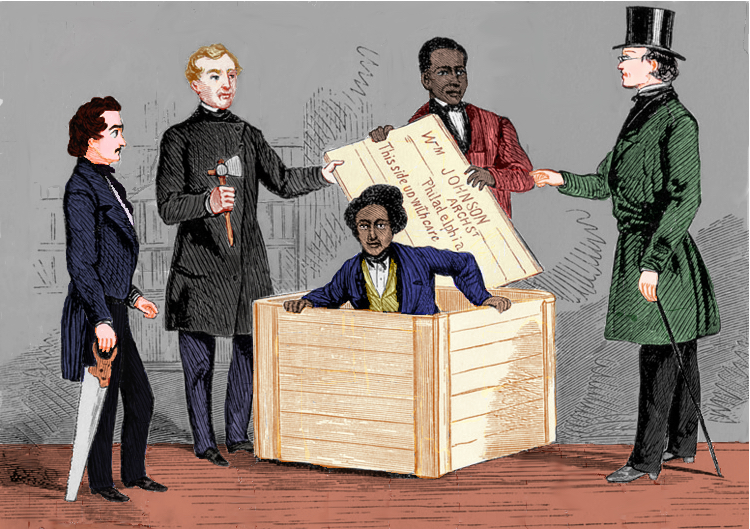

Banner image: The 1849 escape of Henry “Box” Brown from Richmond, Virginia to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was perhaps the most sensational Underground Railroad story of the era. Original illustration from William Still’s Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Forbes (House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

By the 1830s, slavery had essentially ceased to exist in Pennsylvania and New York. Yet slavery in the South remained central to the economic prosperity of these states’ great urban centers, Philadelphia and New York City. As a result, the abolitionist movement there was far smaller than in cities further north, such as Boston and Syracuse, and many local officials were more than happy to cooperate in apprehending and returning enslaved people seeking freedom from bondage. Nonetheless, Philadelphia and New York were critical way stations in the metropolitan corridor through which fugitives from slavery made their way from the Upper South to upstate New York, New England, and Canada. Indeed, the Underground Railroad may be said to have originated in these cities.

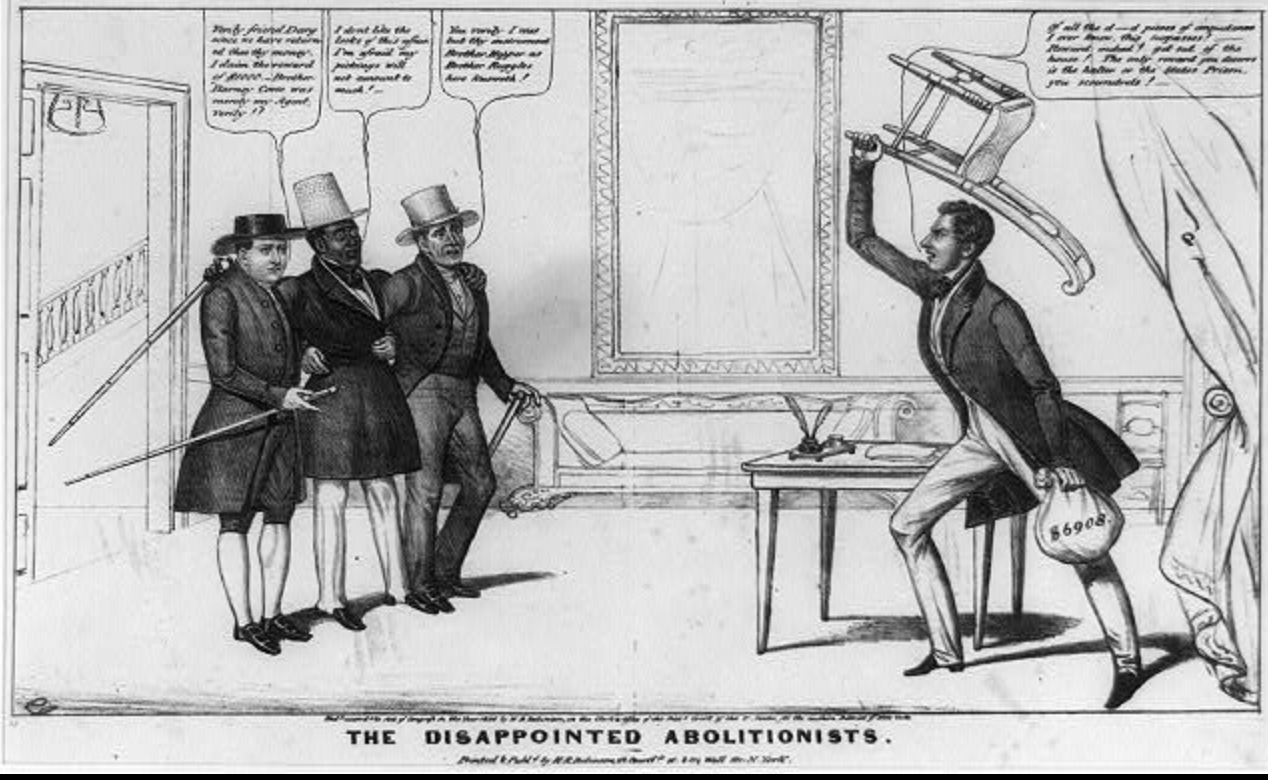

The history of slavery, and of individuals assisting runaway slaves in the Middle Atlantic region goes back to the early colonial days. Not until the 1830s, however, did organized efforts emerge to aid persons fleeing from bondage. In 1835, David Ruggles, a Black activist who called on the antislavery movement to devote its efforts to “practical abolition,” established the New York Committee of Vigilance. Originally focused on combating the kidnapping of free Blacks from city streets for sale into southern slavery, the committee soon began offering assistance to enslaved African Americans seeking freedom.

In 1835, David Ruggles, a Black activist who called on the antislavery movement to devote its efforts to “practical abolition,” established the New York Committee of Vigilance.

1838 political cartoon featuring David Ruggles (center) and other “disappointed abolitionists” in New York City (Library of Congress)

In one form or another, the Committee of Vigilance survived until the Civil War. Its active leaders generally consisted of only a dozen or so individuals, mostly Black, assisted by a few white abolitionists. Ordinary members of the city’s free Black community – the nation’s largest – watched for fugitives on the docks and city streets. Ironically, the low-income occupations to which Blacks in New York were relegated — servants in hotels and private homes, and dockworkers – put them in a strategic position to assist enslaved men and women who accompanied their owners visiting New York and were entitled, according to state law, to freedom. The committee took part in a remarkable range of activities, some legal and public, some secret and against the law. “Practical abolition” included monthly meetings to raise money and report on activities, efforts to expand the rights of free Blacks, and lawyers who went to court attempting to foil kidnappers and prevent the return of alleged fugitives whom authorities had apprehended.

Before the advent of the New York committee, one abolitionist newspaper noted, the plight of fugitives had been a matter “too little thought of by the professed friends of the colored man.”[1] But at its annual meeting in 1838, the American Anti-Slavery Society urged abolitionists “to appoint committees of vigilance, whose duty it shall be to assist fugitives from slavery, in making their escape, or in legal vindication of their rights.”

By 1842, the weekly National Anti-Slavery Standard could report the existence of such organizations “in most of our cities and large towns,” including Philadelphia.[2] New York City had taken the lead, but a broader infrastructure of local individuals and groups committed to assisting those seeking freedom was now in place. In the 1840s, their ability to coordinate their efforts would expand, and collectively they would become known as the Underground Railroad.

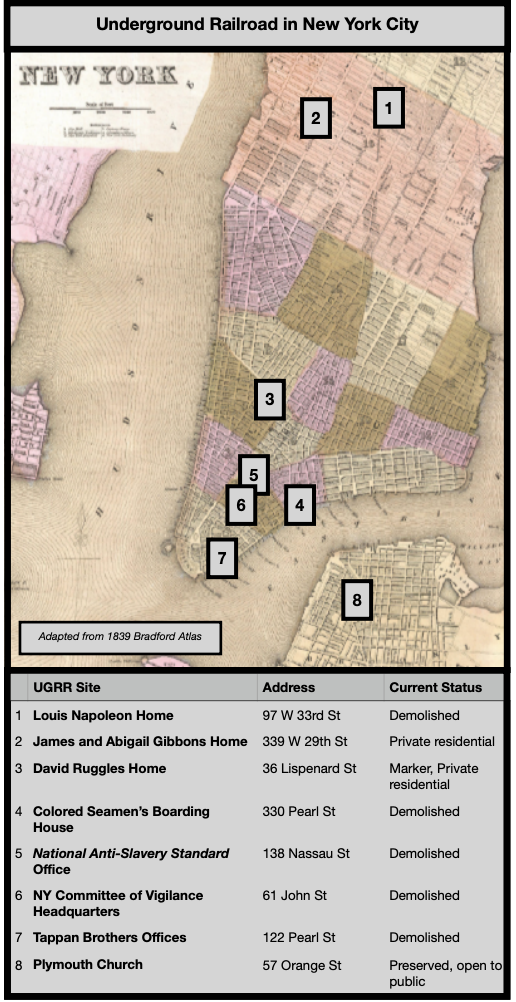

After the abolitionist movement split into competing camps in 1840, followers of William Lloyd Garrison established a second Underground Railroad outpost in New York City, since the Committee of Vigilance was closely associated with the anti-Garrisonian faction led by the New York merchant Lewis Tappan. Centered at the office of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, this new vigilance committee was led by Sydney Howard Gay, the newspaper’s editor, and Louis Napoleon, a Black porter who worked in the office and, although illiterate, took part in numerous activities relating to alleged fugitives including seeking writs of habeas corpus for those who had been captured in New York. Napoleon scoured New York’s docks searching for enslaved people who had concealed themselves on vessels and met runaways dispatched by train from Philadelphia. In one court proceeding, the attorney for a slaveholder sarcastically asked the abolitionist lawyer John Jay II if the Louis Napoleon who had brought the case was the emperor of France. Jay replied: “a much better man.”[3] A third organization assisting fugitives, the Committee of Thirteen, also operated for a few years in New York in the early 1850s. This group of Black abolitionists included the prominent physician James McCune Smith and William P. Powell, who ran the Colored Seamen’s Boarding House near the East River docks.

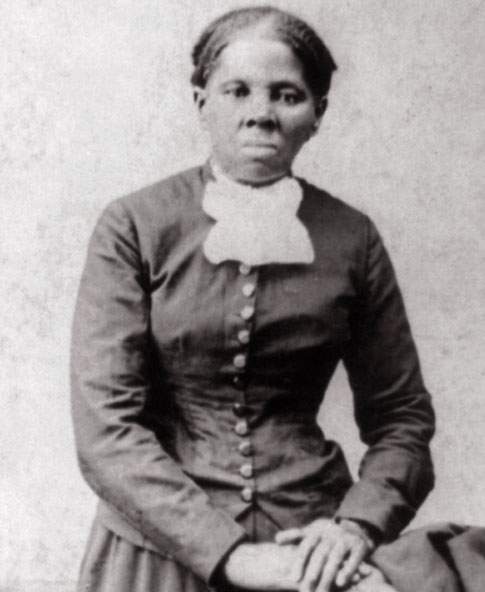

Some of the most celebrated fugitives in American history passed through Philadelphia and New York. They included Frederick Douglass, who found refuge at Ruggles’ home after arriving from Maryland in 1838; Harriet Tubman, who after her own escape made numerous forays into Maryland to lead others out of slavery; Harriet Jacobs, who hid for seven years in her free grandmother’s attic in North Carolina before a sea captain transported her to freedom; and Henry “Box” Brown, who arranged to be shipped in a crate from Richmond to the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee’s office. The passage of the draconian 1850 Fugitive Slave Act did not deter Underground Railroad operatives. The Philadelphia committee forthrightly advertised its meetings in local newspapers and held public fund-raising meetings. “Fugitives from southern injustice are coming thick and fast,” read one of the committee’s public notices in 1854. “The underground railroad never before did so large a business as it is doing now.”[4]

In 1855 and 1856, in two tiny notebooks now available online, which he called the Record of Fugitives, Sydney Howard Gay meticulously recorded the arrival of well over two hundred men, women, and children at his office on Nassau Street, not far from New York’s City Hall.[5] More than half arrived by train via Philadelphia and also appear in a similar notebook (entitled Journal C of Station No. 2 and also digitized) maintained by William Still, the leading spirit of that city’s vigilance committee, who arranged for runaways to be sent to Gay.[6] Taken together the two documents contain a treasure trove of information about both those seeking freedom and how the Underground Railroad in the Middle Atlantic region operated. Not surprisingly, nearly half the enslaved runaways originated in Maryland and Delaware, the eastern slave states closest to free soil. But many also arrived from Virginia and North Carolina, states considerably more distant. Individuals of every age absconded, but most were in their twenties, their prime working years, when their economic value to their owners was at its peak. Three quarters of those seeking freedom were men.

While the popular image of the Underground Railroad tends to focus on lone individuals making their way north on foot, in fact, more of the enslaved who passed through Philadelphia and New York in the mid-1850s escaped in groups, sometimes composed of family members including small children. Many absconded on Captain Albert Fountain’s ship the City of Richmond. Fountain established a regular packet service from Richmond and Norfolk to New York City in the early 1850s. He was not, Still wrote, “averse to receiving compensation for his services,” up to one hundred dollars per slave. He offered to rescue the families of fugitives for a hefty fee. A Black ship carpenter worked with Fountain, informing potential runaways when the vessel was sailing. The ship often stopped at Wilmington, Delaware, to pick up runaways who had been given refuge by Thomas Garrett, a Quaker abolitionist. In Philadelphia, Fountain landed fugitives at night at the foot of Broad Street, where Still arranged for them to be met. Whatever the cost, those seeking freedom certainly appreciated Fountain’s efforts. Thomas Page, who escaped from Norfolk on Fountain’s vessel in 1856, asked Still two years later to “give my love” to the captain and to urge him to visit Boston, “as there are a number of his friends that would like to see him.”[7]

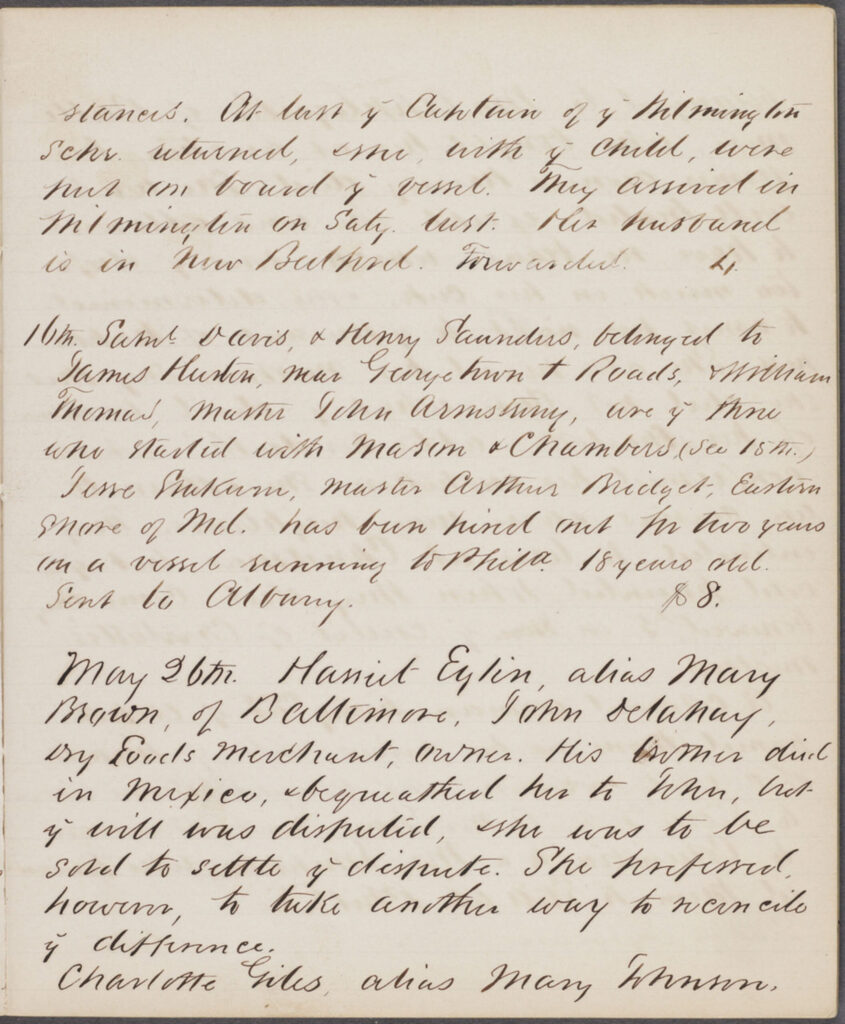

The nation’s rail network expanded rapidly in the two decades before the Civil War and a good number of freedom seekers took advantage of this new technology. Harriet Eglin and her cousin Charlotte Giles of Baltimore borrowed five dollars “on the credit of Charlotte’s mistress” and arranged for a white man, who had been told they were free, to buy their train tickets to Pennsylvania.[8] Many fugitives, of course, did escape on foot, sometimes over long distances. Simon Hill of Appomattox County, Virginia, told Gay he “took … to the woods, and bent his steps northward and in about two weeks reached Philadelphia,” a distance of well over two hundred miles.[9]

Sydney Howard Gay recorded the escape of Harriet Eglin in his Record of Fugitives (Columbia University Libraries)

Alongside the dramatic stories of individual escapes, the records kept by Gay and Still also contain insights into the operations of a key set of Underground Railroad operatives during the 1850s. Gay noted nearly fifty fugitives who reached New York with the assistance of Thomas Garrett from Wilmington. But far more common south of the Mason-Dixon Line was aid from individuals unconnected with any network. Not surprisingly, freedom seekers in slave states tended to approach Black persons, both free and enslaved, for help in initiating or conducting their escapes.

Gay’s operation in New York stood at the nexus of two sets of Underground Railroad networks: one in southeastern Pennsylvania centered on William Still’s office in Philadelphia and including Quaker farm families in the city’s rural hinterlands, both in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and the vigilance committees in New England and upstate New York. Although fugitives reached New York City by many routes, a majority of the persons listed in the Record of Fugitives had been forwarded from Philadelphia. Generally, Still put them on a train, telegraphed ahead announcing their impending arrival, and provided instructions for how to reach Gay’s office or to meet up with Louis Napoleon. An abolitionist from Vermont recalled how, while visiting Gay in 1856, a dispatch arrived from Still giving notice of “‘six parcels’ coming by the train. And before I left the office, the ‘parcels’ came in, each on two legs.”[10] The train from Philadelphia did not cross the Hudson River and usually, Napoleon met fugitives at a ferry terminal in New Jersey or Manhattan. At one point he rented an apartment where they could hide. But Gay also knew persons, including the Quakers James and Abigail Gibbons on Twenty-Ninth Street and various residents of Weeksville, a free Black community in Brooklyn, ready to shelter fugitives until they continued their journeys. The operations were not free of tensions. In 1856, Gay complained to James Miller McKim of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee: “Still is in the habit of sending men here by a train that arrives about 3 a. m. Unless it is absolutely imperative… it should not be done.” He noted that Napoleon had to walk three miles from his home on Thirty-Third Street to reach the ferry terminal.[11]

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, it became more imperative for fugitives from slavery to reach Canada – nowhere in the United States could they feel safe. Gay directed more fugitive slaves to Syracuse, half-way between Albany and the Canadian border, than to all other destinations combined. The site of the Jerry rescue of 1851, Syracuse was known as the Canada of the United States because of its antislavery atmosphere. In Jermain Loguen, himself an escaped slave, Syracuse boasted one of the most effective Underground Railroad operatives in the entire North. In the 1850s, Loguen became known as the city’s “underground railroad king.”[12] His operations, illegal under federal law, were flagrantly public. Sympathetic newspapers reported on the arrival of groups of runaways at Loguen’s home and published annual reports on the number of fugitives who had passed through the city (two hundred in 1855 according to one account). Loguen placed notices in newspapers publicizing the presence of slave catchers in Syracuse, calling on citizens to run them out of town. In 1859, Loguen held a fund-raising event at his residence. The house, according to a local newspaper, was “crowded with visitors and friends of the Underground Railroad,” including “about thirty fugitives.”[13] From Syracuse, men and women seeking freedom were sent to Rochester, where Frederick Douglass’s house was one hiding place, and then on to Buffalo and then Canada, over the recently opened Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge.

In Jermain Loguen, himself an escaped slave, Syracuse boasted one of the most effective Underground Railroad operatives in the entire North.

The outbreak of the Civil War led to an increase in the number of those seeking freedom in the North. Three days after the firing on Fort Sumter, the New York Tribune observed that fugitives were passing through Philadelphia “in far larger numbers than usual.” Runaway slaves, wrote McKim, now traveled “fearlessly by daylight … and by a variety of routes heretofore closed to them.” Anyone “who would now undertake to catch and return a fugitive slave,” he added “would be a fool.”[14]

The war fundamentally transformed the opportunities available to slaves seeking freedom. As soon as federal troops entered a locality, which in Maryland meant from the very beginning of the conflict, Black men and women sought refuge with the Union army or flocked to Washington, DC, now the capital of an antislavery government. No longer did slaves have to reach the North or Canada to find freedom. “An end is put … to the Underground Railroad,” wrote McKim. “I take this opportunity … to thank the contributors to the treasury of the Vigilance Committee, … and to notify them that in all probability we shall have no further call for their aid in this particular line of business.”[15] Many of those who had found refuge in Canada now returned; some went on to enlist in the Union army.

Although the organization ceased to exist, many Underground Railroad operatives continued their efforts to improve the lot of Black Americans. After the Civil War, William Still took part in the fight to integrate the city’s streetcars and secure for Blacks the right to vote, as well as helping to organize a home for orphans of Black soldiers and sailors. When Still died in 1902, a Black correspondent wrote to his son, “there are costly monuments towering toward the sky to men of the Caucasian race for deeds not so great nor so dangerous as his acts in the under-ground Rail Road.”[16] James Miller McKim was instrumental in the creation of the American Freedmen’s Aid Commission, a pioneering effort to assist the emancipated slaves.

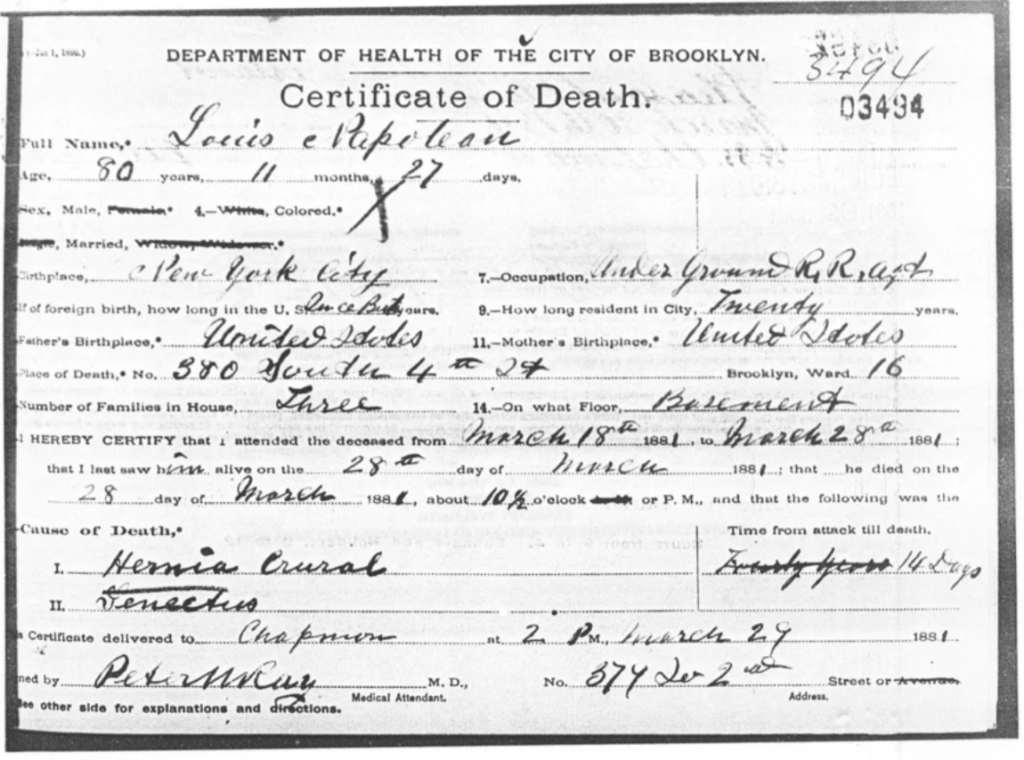

After the war, Sydney Howard Gay achieved widespread recognition for a series of books on American history. In one, he wrote that thanks to the Underground Railroad, thirty thousand slaves had reached “a safe refuge in Canada.” As for the indispensable Louis Napoleon, in the 1870s the New York Tribune published a brief sketch, in a series on “New-York Characters.” “The old man,” it reported, “hobbles painfully” with the aid of a walking stick; “few would have suspected … that he had ever been the rescuer of 3,000 persons from bondage.”[17] Napoleon died in 1881, just days before his eighty-first birthday. His death certificate in New York City’s Municipal Archives recorded his occupation as: “Underground R. R. Agent.”

Louis Napoleon’s 1881 death certificate listed his occupation as “Underground RR agent” (NYC Municipal Archives)

Further Reading

- Bentley, Judith. “Dear Friend”: Thomas Garrett and William Still, Collaborators on the Underground Railroad. New York: Cobblehill Books, 1997.

- Blockson, Charles L. The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania. Jacksonville, NC: Flame International, 1981.

- Calarco, Tom and Don Papson. Secret Lives of the Underground Railroad in New York City: Sydney Howard Gay, Louis Napoleon, and the Record of Fugitives. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.

- Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W.W. Norton, 2015.

- Hodges, Graham Russell Gao. David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Hunter, Carol M. To Set the Captives Free: Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen and the Struggle for Freedom in Central New York 1835-1872. New York: Garland, 1993.

- Sernett, Milton C. North Star Country: Upstate New York and the Crusade for African American Freedom. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2002.

- Still, William. The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872).

Citations

[1] Liberator, May 18, 1838.

[2] National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 11, 1842.

[3] New York Times, October 2, 1857.

[4] Pennsylvania Freeman in Provincial Freeman (Toronto), July 8, 1854.

[5]. https://exhibitions.library.columbia.edu/exhibits/show/fugitives.

[6] https://hsp.org/history-online/digital-history-projects/pennsylvania-abolition-society- papers/journal-c-of-station-no-2-william-still-1852-1857-0.

[7] William Still, The Underground Railroad (rev. ed. Philadelphia, 1878), 159-62, 333.

[8] Record of Fugitives, May 26, 1856.

[9] Journal C of Station No. 2, August 29, 1855; Record of Fugitives, August 30, 1855.

[10] Still, Underground Railroad, 583.

[11] Gay to James Miller McKim, September 11, 1858, Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection, Cornell University.

[12] Carol M., Hunter, To Set the Captives Free: Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen and the Struggle for Freedom in Central New York 1835-1872 (New York, 1993), 151.

[13] Syracuse Journal in Douglass’ Monthly, March 1859.

[14] New York Tribune, April 15, 1861; National Anti-Slavery Standard, December 28, 1861.

[15] National Anti-Slavery Standard, December 14, 1861.

[16] Allen W. Turnage to William H. Still, August 9, 1902, American Negro Historical Society Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[17] New York Tribune, October 12, 1875.

ERIC FONER is a former DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University. Foner received his doctorate from Columbia and has also studied at Oxford. Foner has served as the president of the Organization of American Historians, American Historical Association, and Society of American Historians. Foner has served as a consultant of several historical sites and museums for the National Parks Service. Foner’s publications include: The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (Norton, 2010) and Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (Norton, 2015). The Fiery Trial won the Pulitzer Prize for History, the Bancroft Prize, and The Lincoln Prize. Gateway to Freedom was awarded with the American History Book Prize by the New-York Historical Society.

ERIC FONER is a former DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University. Foner received his doctorate from Columbia and has also studied at Oxford. Foner has served as the president of the Organization of American Historians, American Historical Association, and Society of American Historians. Foner has served as a consultant of several historical sites and museums for the National Parks Service. Foner’s publications include: The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (Norton, 2010) and Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (Norton, 2015). The Fiery Trial won the Pulitzer Prize for History, the Bancroft Prize, and The Lincoln Prize. Gateway to Freedom was awarded with the American History Book Prize by the New-York Historical Society.

Related Works and Appearances by Eric Foner

- Partial View Gateway to Freedom (2015) via Google Books

- Politico, “When the South Wasn’t a Fan of States’ Rights,” January 23, 2015

- Interview with History Channel (Video // 2:45 min)

- C-SPAN “After Words” Interview, March 22, 2015 (Video // 130 min)

- Conversation with David Blight at Yale, April 17, 2015 (Video // 96 min)