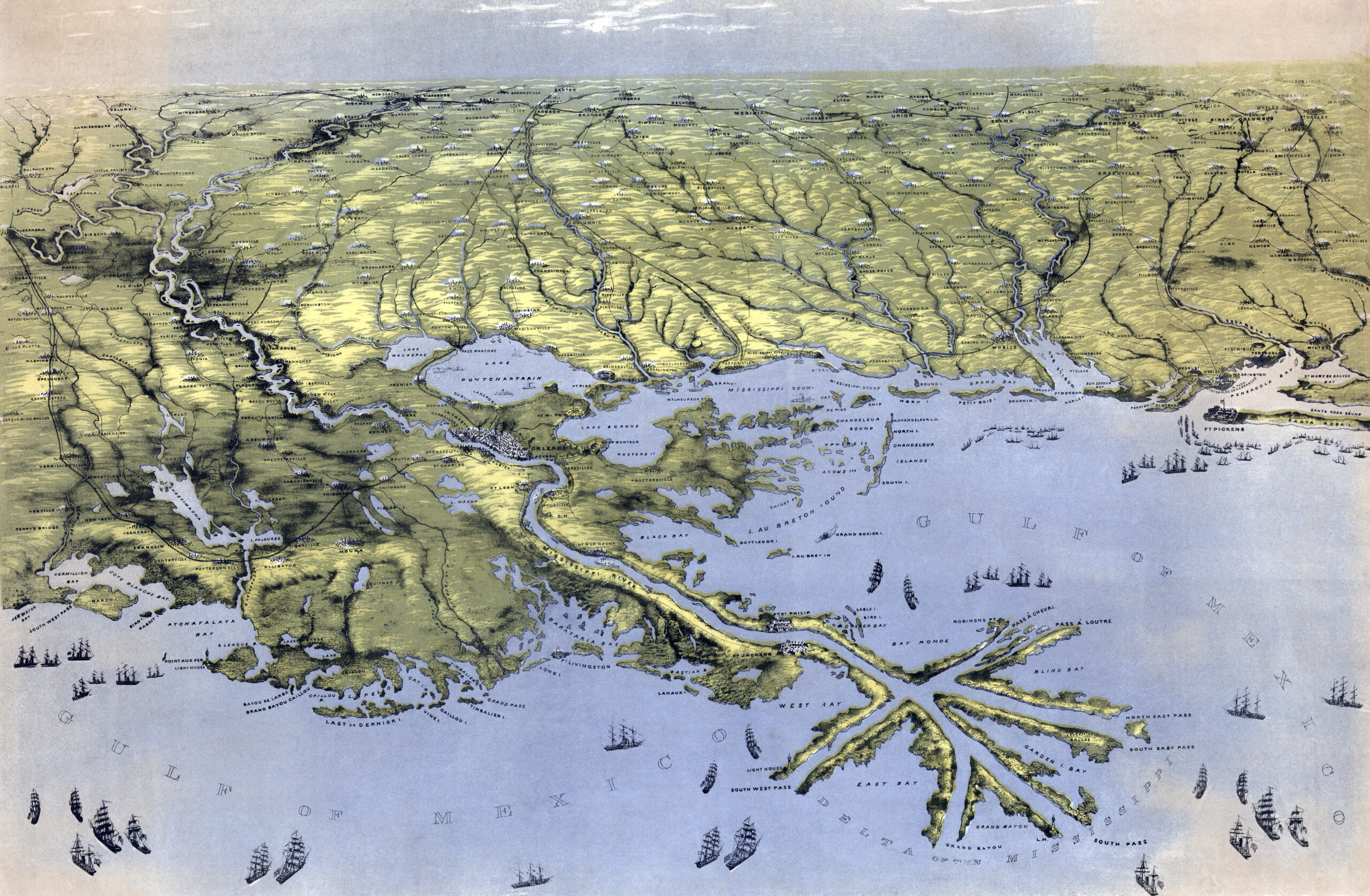

Banner image: Many freedom seekers from the Deep South headed further south, rather than north, in hopes of reaching Mexico’s free soil (House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

The first thing to go missing from Octave Delahoussaye’s sugar plantation in the summer of 1822 was a gun. Replacing it was only a minor inconvenience for the wealthy Louisiana planter, who owned a share of the profitable Attakapas Steam Company, in addition to his plantation on the banks of the Atchafalaya River, about a hundred miles west of New Orleans. But Delahoussaye feared that this loss would lead to others. Firearms tended to disappear at the same time as enslaved people, and nearly a hundred freedom seekers had escaped from the parishes surrounding Delahoussaye’s plantation over the last several months. Fourteen slaves fled from the nearby town of Grande Prairie. Seventy-five were unaccounted for in neighboring Vermillion Parish.

Enslaved people in western Louisiana could escape in any number of directions. To the east was the Mississippi River, where freedom seekers snuck aboard steamboats bound for the northern states. To the west were bayous where enslaved people could lay out for weeks and sometimes months—a temporary absenteeism that was one of the most common forms of escape. But the enslaved people who escaped from western Louisiana in the summer of 1822 seemed to be headed to another destination: Mexico, which had won its independence from Spain the previous year on the revolutionary principle of universal equality.

Several weeks after the gun went missing from Octave Delahoussaye’s plantation, an enslaved man named Joe disappeared, along with a horse, bridle, and saddle. Suspecting that Joe was headed toward Mexico, Octave Delahoussaye hired slave catchers to pursue him. Not far from the plantation, Joe was caught with the horse and the gun. Though he had not reached the Sabine River—then the border between Mexico and the United States—he refused to give himself up, citing “the common law.”[1] It is unclear why Joe would invoke common law in a civil law jurisdiction like Louisiana where it did not apply. Perhaps he was mistaken, or perhaps he was referring in a broader sense to “the common law” of Mexico and the United States. If both nations had been founded on the principle of equality, then how could he be held in bondage in either?

The promise of equality from neither Mexico nor the U.S. was enough to guarantee freedom—not for Joe, and not for any freedom seeker. Liberty had to be defended, not simply enjoyed; it came not by simply reaching a jurisdiction that had abolished slavery, but by acquiring the means of claiming freedom when it was called into question. African Americans could only be said to be free if they exercised the rights of freedom and were able to protect those rights by violence or the law. For this reason, that the story of this escape route is as much about freedom seekers as it is about the laws they invoked and the communities that they forged to defend their liberty. It is as much about Joe, as it is about his gun and “the common law.”

The promise of equality from neither Mexico nor the U.S. was enough to guarantee freedom—not for Joe, and not for any freedom seeker. Liberty had to be defended, not simply enjoyed; it came not by simply reaching a jurisdiction that had abolished slavery, but by acquiring the means of claiming freedom when it was called into question.

The experience of freedom seekers in Mexico depended on when they escaped. In the 1820s, Mexico’s enslaved population was concentrated in two regions: the cotton-producing province of Téjas, as well as the sugar-growing and timber-harvesting states of Veracruz, Chiapas, and Yucatán. Mexico’s leaders feared that enslavers in these regions would revolt against abolition—a revolt that the fledgling government would find difficult to suppress.[2] To end slavery without interfering with “property” rights, the Mexican government generally favored gradual emancipation policies. In 1824, Mexico’s Congress banned the importation of enslaved people from abroad, promising freedom to those imported in violation of the law. Mexico’s enslaved population, which numbered no more than ten thousand, seemed unlikely to sustain itself without foreign imports.

Enslavers from the United States, who immigrated to the Mexican province of Téjas in the 1820s, disregarded this law. Mexico’s Congress responded by passing new legislation on April 6, 1830, which not only reiterated the ban on the importation of enslaved people, but also prohibited all future immigration from the United States. U.S. citizens continued to immigrate with their enslaved people anyway. Mexico’s consul in New Orleans, Francisco Pizarro Martínez, documented how they forced “individuals of color” to sign labor contracts for periods of “sixty, seventy, eighty, and up to ninety years—and this in exchange for an insignificant sum.”[3] To stop immigrants from importing enslaved people disguised as indentured servants, the legislature of Coahuila y Téjas (of which the province of Téjas was a part) in 1832 limited the terms of any labor contract to ten years.

Enslaved people claimed their freedom under these laws. In 1831, four enslaved people secured their liberty before the local courts of Milperias, Veracruz by arguing that their owner, a U.S. citizen named Charles Rivers, had imported them in violation of Mexico’s law against the slave trade.[4] That same year, three enslaved men and one enslaved woman won their freedom in Nacogdoches, Téjas, on the grounds that their enslavers had imported them illegally from Louisiana.[5] In 1832, Peter and his son John escaped from eastern Téjas and petitioned for their freedom before the mayor of San Antonio de Béxar. They, too, secured their freedom.[6]

Although enslaved people imported to Mexico had a claim to liberty, those who escaped on their own initiative did not. In the spring of 1832, when three enslaved people escaped from Louisiana to Téjas, Mexican Col. José de las Piedras ordered them returned. Three years later, a freedom seeker named Jean Antoine escaped in the hold of a ship bound from New Orleans, Louisiana to Campeche, Mexico. But the authorities in Campeche arrested him on his arrival and handed him over to the next ship bound for Louisiana.

The Mexican government only emancipated enslaved people under certain circumstances, but even this limited promise posed a threat to slavery in the Mexican province of Téjas. Enslavers assumed that they would be able to violate Mexico’s antislavery laws without consequence—an assumption that enslaved people who claimed their freedom under these laws proved false. The Mexican government sought to encourage these freedom suits. In 1834, Mexico’s vice president dispatched a secret agent to Téjas with instructions to “seek by every possible and prudent means to make it known to the slaves who have been brought into the Republic in circumvention of the law, that [the law] gives them freedom by the mere act of stepping on the territory of the Republic.”[7] In 1835, President Antonio López de Santa Anna replaced Mexico’s federalist system with a centralist one, which would have further eroded the enslavers’ abilities to disregard unfavorable legislation. Rather than risk forfeiting their “property,” they revolted, securing the independence of the Republic of Texas in 1836.

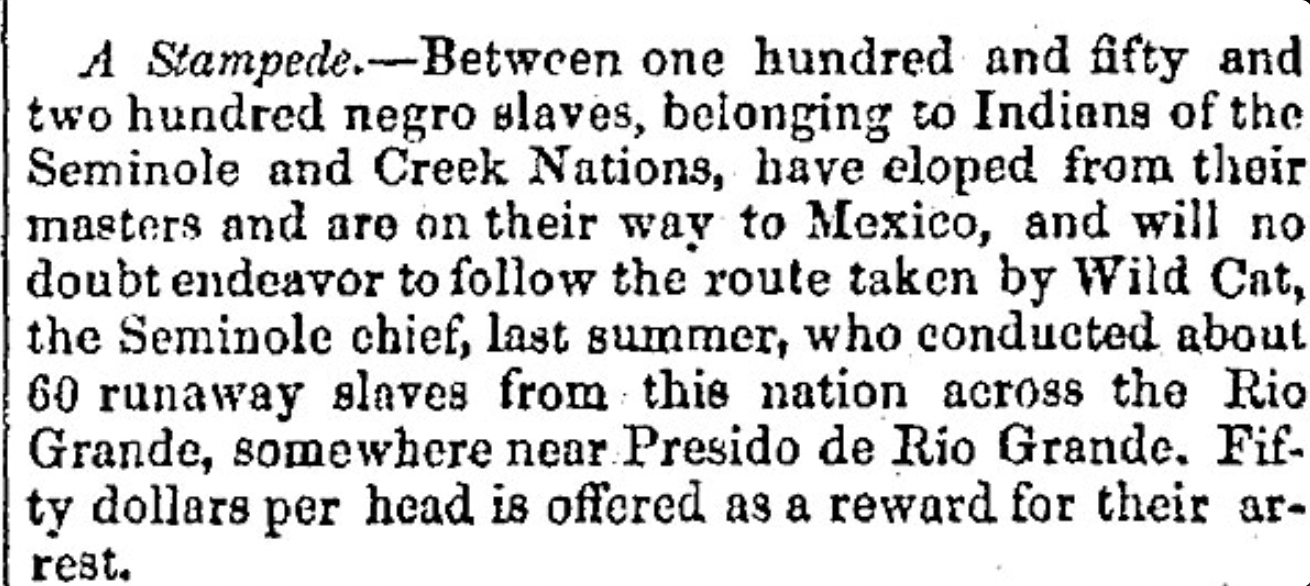

In 1837, a year after the end of the Texas Revolution, Mexico’s Congress abolished slavery. Abolition galvanized international support for Mexico and made it more difficult for the Republic of Texas to secure diplomatic recognition from nations such as Great Britain that opposed human bondage. Abolition also served a larger geopolitical purpose. As news of Mexico’s abolition policy spread, Texans complained that their enslaved people displayed “a very refractory disposition” and blamed the Mexican government for sending emissaries “to excite an insurrection.”[8]

Abolitionist newspapers touted reports in 1850 claiming that hundreds of freedom seekers were successfully fleeing to Mexico in a series of stampedes (The Liberator, December 13, 1850)

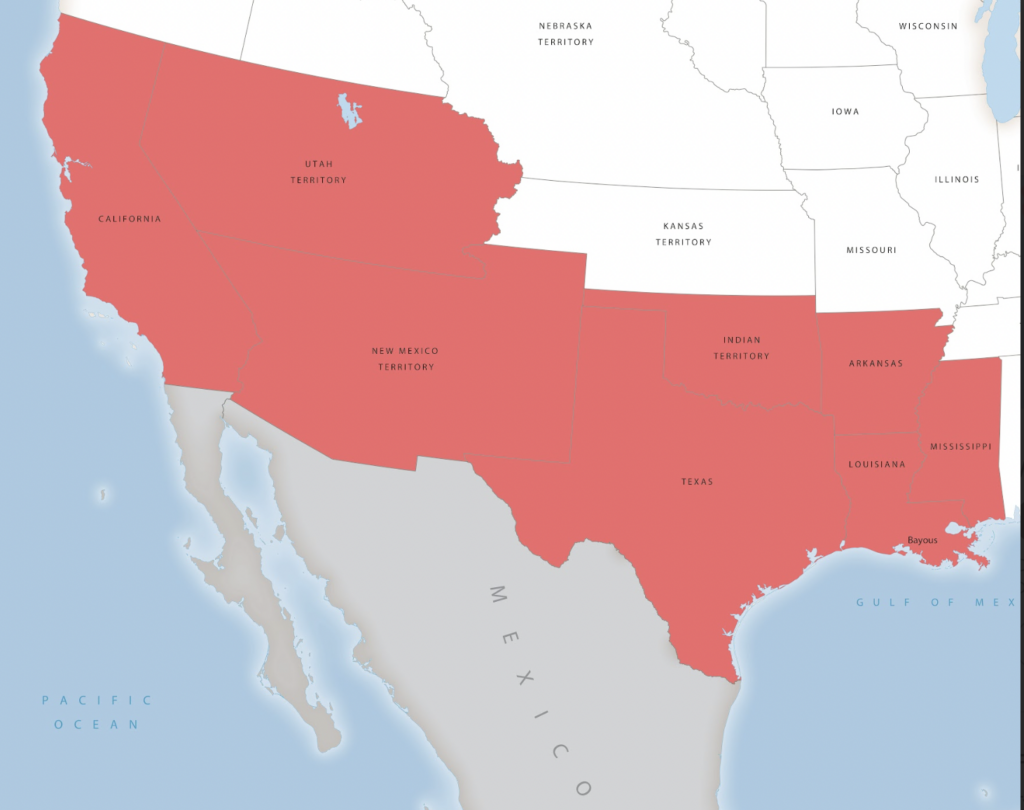

Abolition did not prevent the United States from annexing Texas in 1845 or provoking a war with Mexico that resulted in the conquest of what is now California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, and parts of Colorado. Yet Mexico’s antislavery policies were a powerful weapon in the hands of a weak government: they were not overtly belligerent—the northern states and Canada had adopted similar measures—but they threatened slavery in ways that these other laws did not. In contrast to Canada, Mexico directly bordered the U.S. South. Moreover, this border was not along the southern seaboard, where a century of intensive farming had exhausted the soil, but adjacent to the rich bottomlands of the Mississippi Valley, where nearly a million enslaved people from the Upper South had been driven to sow, plant, and harvest cotton.

[Mexican] Abolition did not prevent the United States from annexing Texas in 1845 or provoking a war with Mexico that resulted in the conquest of what is now California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, and parts of Colorado. Yet Mexico’s antislavery policies were a powerful weapon in the hands of a weak government…

After the abolition of slavery in Mexico, enslaved people began to escape to the south in greater numbers. They fled from Texas, Louisiana, Indian Territory, and even as far west as the California gold mines.[9] Some traveled by sea, stealing canoes and flatboats along the eastern coast of Texas or concealing themselves on board the ships docked at New Orleans. But most escaped by land, traveling alone or in groups across inhospitable terrain, overgrown with low scrubby trees and thick underbrush, until they reached the boundary between Mexico and the United States.

In Mexico, there was no organized network, only the occasional ally, and few newspapers in the Southwest referred to this route as an Underground Railroad as a result.[10] Still freedom seekers did sometimes receive help. According to family lore, Silvia Webber, a formerly enslaved woman, and her white husband, John Ferdinand Webber, helped freedom seekers escape to Mexico from their ranch outside of Hidalgo, Texas. The Webbers were not the only mixed race couple to help enslaved people escape to Mexico: their neighbors, Matilda and Nathaniel Jackson, apparently did too.

In Mexico, there was no organized network, only the occasional ally, and few newspapers in the Southwest referred to this route as an Underground Railroad as a result.

Two options awaited most freedom seekers (known as esclavos profugos) in Mexico. The first was to join Mexico’s military colonies, a series of outposts along the northeastern frontier that defended against foreign invaders and Native peoples. Their military service entitled them to land and citizenship, but these benefits came at the risk of their lives—and at the cost of their participation in Mexico’s campaign against Native peoples. Not every freedom seeker joined the military colonies: they could also seek employment in cities like Matamoros, which had a growing Black population, hailing from Haiti, the British Caribbean, and the United States, or they could hire themselves out to local landowners, who were often in need of extra hands. These freedom seekers enjoyed legal protections that enslaved people were denied in the United States. They could file suit in cases of mistreatment, and they had the right to seek new employment for any reason. Still, these freedom seekers encountered many of the same coercive labor practices, including debt peonage, that were common in post-emancipation societies.

These possibilities, though imperfect, reshaped the geography of freedom in North America. In 1851, a concerned citizen wrote to the governor of Texas that “the frequent occurrence of the running off of our negroes is becoming so great an evil that it calls for a remedy.”[11] That same year, a British diplomat reported that southern Texas was “non-slaveholding” due to its “proximity to Mexico.”[12] Diplomats from the United States tried to negotiate an extradition treaty with Mexico that would return freedom seekers to their enslavers. But negotiations failed in 1850—and 1851, 1853, and 1857.

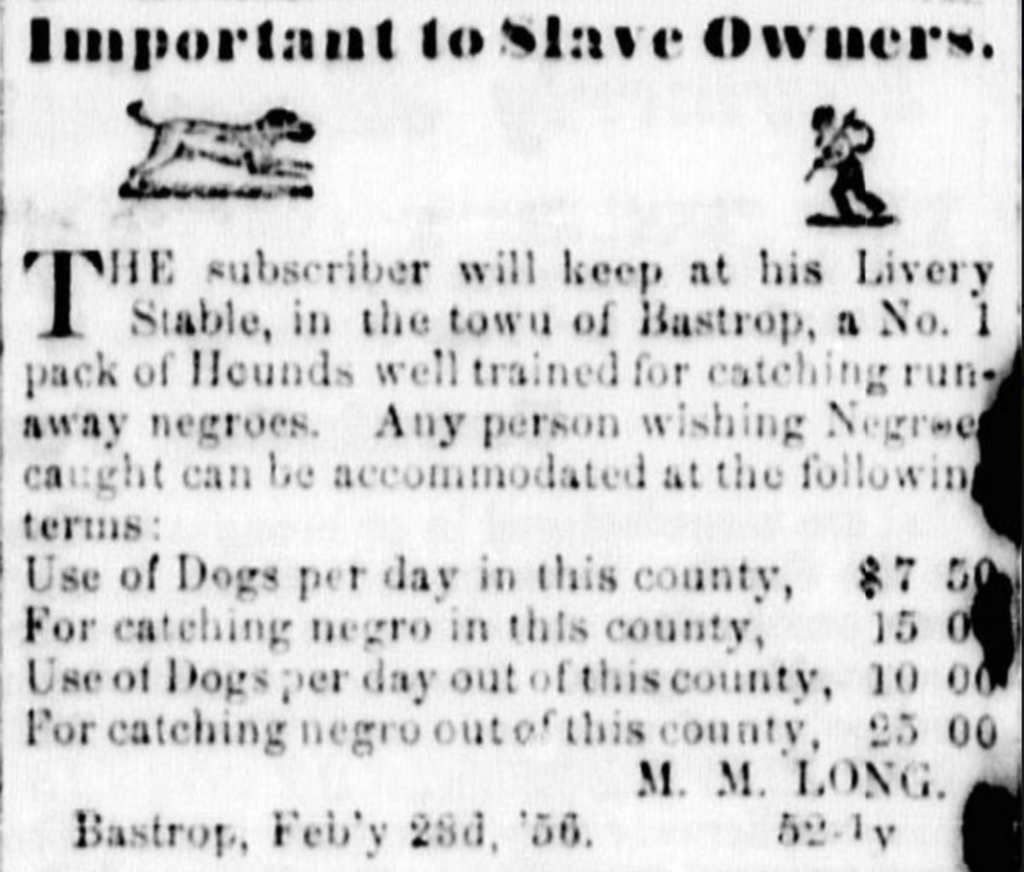

1857 advertisement in Texas for renting slave-catching dogs (Texas Runaway Slave Project)

Undeterred, bounty hunters scoured the ranches and haciendas of northeastern Mexico, searching for enslaved people. But they faced resistance from freedom seekers and Mexican citizens alike. On August 20, 1850, two Louisianans broke into Manuel Luis del Fierro’s house in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, and tried to kidnap his maid, a freedom seeker named Mathilde Hennes. Hennes put up a fight, and on hearing the commotion, Del Fierro rushed to her aid, threatening to shoot the two men. One of the kidnappers managed to escape, but the local authorities arrested the other: Mathilde Hennes’ former enslaver, William Cheney. While Cheney sat in prison, Judge Justo Treviño of the District of Northern Tamaulipas began an investigation into the attempted kidnapping.[13]

The resistance that these kidnappers faced was not unusual. In the fall of 1851, a community in northern Coahuila took up arms to defend a family of freedom seekers from being kidnapped by a slave catcher named Warren Adams. Several months later, Mexican soldiers stood guard on the Rio Grande with two field pieces to stop two hundred Texans from crossing the river, likely to kidnap freedom seekers. On July 5, 1859, eight armed kidnappers tried to seize a “free Mexican negro servant” near Paso del Norte, but local citizens arrested the kidnappers and forced them to pay a fine, surrender their arms, and pledge never to return to Mexico.[14]

Not all Mexicans tried to protect freedom seekers. Rarely do policies inspire lockstep compliance. Any single violation, therefore, is less informative than the response to it. Disregarding a law that is routinely ignored might not merit comment, while disregard for a foundational legal principle would provoke outrage. And in Mexico, the response of the authorities to the accomplices of kidnappers was revealing. In 1851, two Mexicans were condemned to four years in prison for helping a Texan kidnap a Black man. By order of the governor of Coahuila, any property belonging to these accomplices was auctioned off, and the proceeds used to buy the freedom of kidnapped freedom seekers. Three years later, a Mexican citizen who aided an expedition to kidnap freedom seekers living “under the protection of the laws” was convicted of treason.[15]

Mexico’s laws were significant, but they did not, in and of themselves, guarantee freedom to enslaved people. This was the work of freedom seekers and their Mexican neighbors. Together, their actions suggest that the Underground Railroad did not end at the Rio Grande, and that it was not limited to individuals in the United States. Rather, it extended into Mexico, and included the communities who helped enslaved people to defend their freedom.

Further Reading

- Baumgartner, Alice L. South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War. New York: Basic Books, 2020.

- Cornell, Sarah. “Citizens of Nowhere,”: Fugitive Slaves and Free African Americans in Mexico, 1833-1857.” Journal of American History (Sept, 2013): 351-74.

- Gurza-Lavalle, Gerardo. “Against Slave Power? Slavery and Runaway Slaves in Mexico-United States Relations, 1821-1857.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 35:2 (Summer 2019): 143-70.

- Nichols, James David. “The Line of Liberty: Runaway Slaves and Fugitive Peons in the Texas-Mexico Borderlands.” Western Historical Quarterly 44 (Winter 2013): 413-33.

- Schwartz, Rosalie. Across the Rio to Freedom: U.S. Negroes in Mexico. El Paso: University of Texas Press, 1975.

- Tyler, Ronnie C. “Fugitive Slaves in Mexico.” The Journal of Negro History 57:1 (Jan 1972), 1-12.

Citations

[1] Unsigned extract, St. Martinsville, July 9, 1822, box 1, Slavery Collection, Louisiana State University Special Collections.

[2] The threat of revolt was credible, as would become clear in 1829, when Mexico’s President Vicente Guerrero, himself of African descent, issued a decree abolishing slavery. The resulting outcry led Guerrero to exclude Téjas from the decree and for Mexico’s Congress to overturn the decree altogether.

[3] Francisco Pizarro Martinez to Manuel de Mier y Teran, February 5 de 1832, Folder 9, File 20, Archivo de la Embajada Mexicana en los Estados Unidos (AEMEUA), Archivo Histórico de la Secretaría de Relactiones Exteriores (SRE).

[4] Ramon Hoyos to Governor of Veracruz, “Muy Reservado,” n.d. 1831, f. 83, vol. 32, Pasaportes, Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City (AGN).

[5] Sr Comandante Gral de este departamento to Alcalde de Austin, February 16, 1831, f. 225, vol. 57, Transcripts of Nacogdoches Archives, Blake Transcripts, Texas State Archives (TSA).

[6] Ramón Musquiz to Governor of Texas, June 3, 1832, folder 55, box 22, Fondo Jefatura Política de Béxar, Archivo General del Estado de Coahuila (AGEC). “Reminiscences of Western Texas—No. XII,” The Indianola Bulletin vol. 3, no. 9 (April 26, 1854), 1.

[7] “Confidential Instructions” in Juan Almonte, Almonte’s Texas: Juan N. Almonte’s 1834 Inspection, Secret Report & Role in the 1836 Campaign, Jack Jackson, ed. (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2005), 40

[8] “Mexican emissaries,” Telegraph and Texas Register, 10:40 (October 1, 1845), 2.

[9] “Fugitive Slave Case in the South” Tri-Weekly State Times, Vol 1., No. 11, ed. 1 December 8, 1853.

[10] The only source that I have found referring to the southern route as an Underground Railroad was “Stampede of Slaves,” Colorado Citizen, vol. 1, no. 8, (September 12, 1857), 2. No equivalent term, to my knowledge, existed in Mexico.

[11] Gideon Linceceum to Peter Bell, February 13, 1851, folder 18, box 301-20, Peter Hansborough Bell Papers, TSA.

[12] Viscount Palmerston to Consul Lyon, Foreign Office, December 5, 1851, n.p. , FO 701/27, National Archives, Kew.

[13] Testimony of Manuel Luis del Fierro, Case against William Henry brought before Lic. Justo Treviño, Judge of Northern Tamaulipas, 3-5-13, SRE. Cheney remained in jail at least until September 14, 1850. See “Diligencias sobre encarcelacion bajo de fianza de Don Eduardo Cheney,” folder 911, box 35, Justicia, Archivo Municipal de Matamoros. I’m grateful to James David Nichols for sharing this document with me.

[14] Diffenduffer to Cass, July n.d., 1859, vol. 1 (microfilm: reel 1), M184: Despatches from U.S. Consuls in Ciudad Juárez, General Records of the Department of State, 59 (National Archives, Washington, D.C.).

[15] Serapio Fragua to Sr Com Municipal de la Villa de Muzquiz, October 1, 1854, folder 102, box 9, Muzquiz Collection, Beneicke Rare Books and Manuscript Library. Aguilar to Governor of Coahuila, October 21, 1854, exp. 9, folder 7, box 8, Fondo Siglo XIX, AGEC. Ayuntamiento to Presidencia, November 8, 1851, f. 54, exp. 25, Archivo Municipal de Guerrero, AGEC. Manuel Rejon to Alcalde de Nava, October 28, 1860, exp. 5, folder 13, caja 32, FPMN, AGEC.

Author Profile

ALICE L. BAUMGARTNER teaches History at the University of Southern California. Baumgartner is the author of South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to Civil War (Basic Books, 2020), which was a New York Times’ Editors’ Choice and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times book prize in history. Baumgartner graduated from Yale University with a B.A in History, received an M.Phil in Latin American Studies from the University of Oxford, and completed her doctorate from Yale University.

ALICE L. BAUMGARTNER teaches History at the University of Southern California. Baumgartner is the author of South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to Civil War (Basic Books, 2020), which was a New York Times’ Editors’ Choice and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times book prize in history. Baumgartner graduated from Yale University with a B.A in History, received an M.Phil in Latin American Studies from the University of Oxford, and completed her doctorate from Yale University.