Banner image: A group of 28 armed freedom seekers successfully fled from Cambridge, Maryland in October 1857, original illustration by Wilbur Osler, colorized by Amanda Donoghue (House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

The two most important things about the Underground Railroad in and around Washington, DC are that it was centered south of the Mason-Dixon Line and that it was a biracial effort. Although slavery was legal in Washington, the city had from its foundation during the 1790s attracted Black people escaping on their own from their owners in Maryland and Virginia. This was to a large degree because those who sought freedom could merge into the District of Columbia’s large free Black population. From the start, the freedom seekers, once they reached Washington, also received assistance from some white residents, including attorneys, businessmen, and evangelicals, all influenced by the northern abolitionist movement.

Between 1842 and 1844, the clandestine escape network centered in Washington took shape. Charles T. Torrey and Thomas Smallwood led the effort.

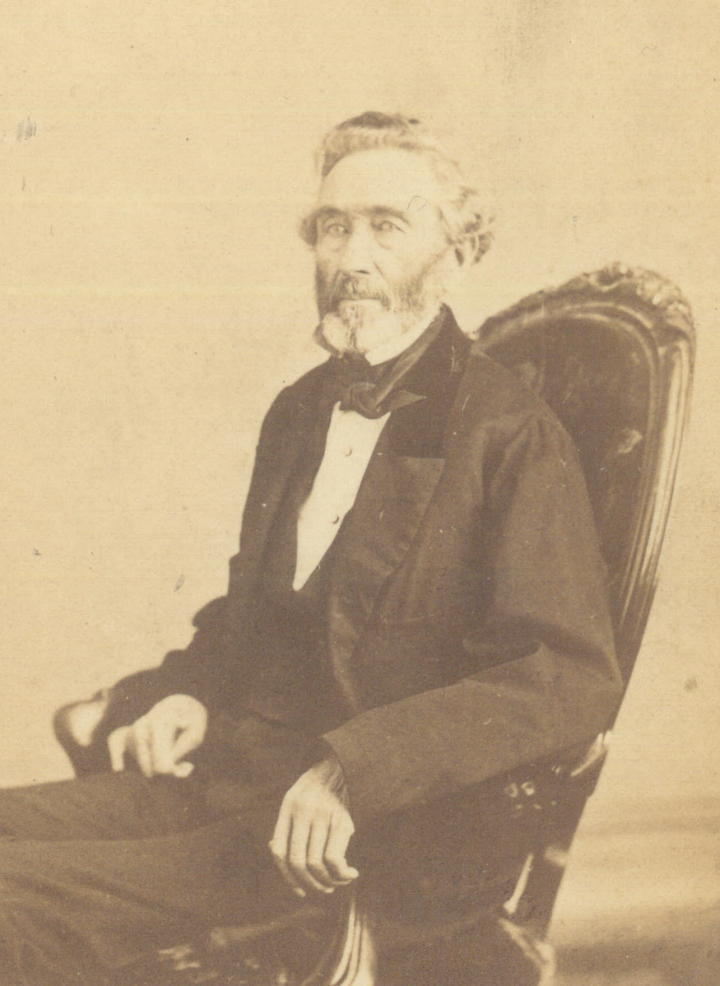

Charles Torrey (House Divided Project)

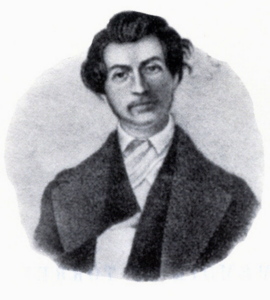

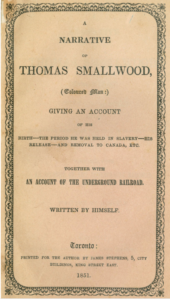

Between 1842 and 1844, the clandestine escape network centered in Washington took shape. Charles T. Torrey and Thomas Smallwood led the effort. Torrey was a white Congressional minister from Massachusetts, who had graduated from Yale College. Smallwood was a formerly enslaved Black man from Prince George’s County, Maryland, who had become a well-to-do shoemaker and a worker at the Washington Navy Yard.[1] When Torrey came to the city from Boston in 1842 as a correspondent for antislavery newspapers, he worked publicly with a group of antislavery northerners, including Whig congressmen and antislavery congressional lobbyists. These men, although often condescending toward African Americans, helped create a biracial antislavery community on which the regional Underground Railroad depended. Soon after Torrey, who had been arrested in Baltimore for reporting on a slaveholders’ convention, arrived in Washington, Smallwood contacted him at Torrey’s 13th Street boarding house. According to Smallwood, Torrey “immediately informed him” of a plan to rescue a Black family that Secretary of the Navy George F. Badger of North Carolina was intending to sell south.[2]

The plan fell through when the wife told Smallwood that her husband preferred to raise money in the North to purchase hers and their children’s freedom rather than risk an escape attempt. But during the following months, Smallwood, Torrey, Smallwood’s wife Elizabeth, and Torey’s southern white landlady, Mrs. Padgett, created what Smallwood called “our new underground railroad.” [3] They provided organization for slave escapes from Washington and its vicinity that had been lacking.

The biracial escape network they led stretched from Washington northward and to a lesser extent southward. It included white Quakers in Delaware and southern Pennsylvania, the Black-led Philadelphia vigilance committee (known then as the Vigilant Association), and white abolitionists in Albany, New York. The network also actively involved those seeking freedom, including many who provided funds and logistical support for northward journeys. At times Smallwood or Torrey personally transported or led freedom seekers northward. On other occasions, they hired Black men hoping to earn help for their families, to do this dangerous work. Jacob Gibbs, a free African American, headed an Underground Railroad operation centered in Baltimore, similar to, and connected with, the one in Washington. The network involved secret meeting places where freedom seekers could rendezvous with their guides. Operatives also established “places of deposit between Washington and Mason’s and Dixon’s line” to house their “passengers.”[4] An important aspect of the network was the role of women. A division of labor by gender existed within these organizations. Men recruited and guided; women harbored. But the gender line was permeable as men sometimes harbored and women sometimes planned and guided.

Thomas Smallwood’s narrative detailed Underground Railroad operations around Washington, DC in the 1840s Cornell University)

Torrey’s and Smallwood’s leadership of the Washington Underground Railroad soon began to end, however. In August 1842 Torrey barely escaped arrest as he led fifteen men, women, and children north. Shortly thereafter he moved with his wife and children, who had remained in Massachusetts while he was in Washington, to Albany. There he became editor of the Tocsin of Liberty newspaper, which he renamed the Albany Patriot. This left Smallwood in charge of an operation that by October 1842 had helped about 150 freedom seekers reach the North. Yet by the following June, Smallwood had dispatched only nine additional people and had become fearful of arrest. Several of those he helped escape had been recaptured and he came to distrust several of the Black men he employed as agents. He left for Toronto, Canada, on June 30 and moved his family to that city in early October.[5]

Following their relocations, Torrey and Smallwood attempted to continue their Washington-centered Underground Railroad efforts. In 1843, with support from Thomas Garrett, a white Quaker abolitionist located in Wilmington, Delaware, they drove a wagon south to the city to help as many as they could flee from slavery. But in Baltimore, as they returned northward, the Washington Auxiliary Guard, tipped off by a Black informant, captured ten of those who were trying to escape, while Torrey and Smallwood barely avoided arrest. This ended the two men’s collaboration, as Smallwood returned to Toronto and Torrey moved his base to Philadelphia. Thereafter Torrey made a series of forays into Virginia and Maryland that eventually led to his arrest, imprisonment in Baltimore Jail, and death there from tuberculosis in May 1846.

Yet the Underground Railroad continued in Washington even though escaping from slavery remained dangerous. An unassisted escape attempt in the Washington area demonstrated this reality. In July 1845 approximately 75 armed enslaved men headed north from Charles County, Maryland, located to the southeast of the city. The men hoped to reach Pennsylvania. Instead, white patrollers intercepted them, wounding many, during two violent encounters, and returned most of them to slavery. It is not surprising, therefore, that Black and white antislavery activists in Washington, during 1845 and 1846, emphasized purchasing the freedom of individuals threatened with sale south, instead of escape. Aimed especially against sale south by slave traders, purchasing freedom, like aided escapes, sought to further weaken slavery in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia.[6]

In July 1845 approximately 75 armed enslaved men headed north from Charles County, Maryland, located to the southeast of the city. The men hoped to reach Pennsylvania. Instead, white patrollers intercepted them, wounding many, during two violent encounters, and returned most of them to slavery.

William L. Chaplin, like Torrey, a white New Englander, joined these efforts. He had arrived in Washington, in December 1844 as correspondent for the Albany Patriot. Although Chaplin periodically left the city, its Black community inspired him. He attended Black churches and thereby learned of the anguish Black families suffered. At first Chaplin restricted himself to purchasing freedom. But by 1848 it had become clear that this tactic had failed in preserving Black families and lessening suffering.[7]

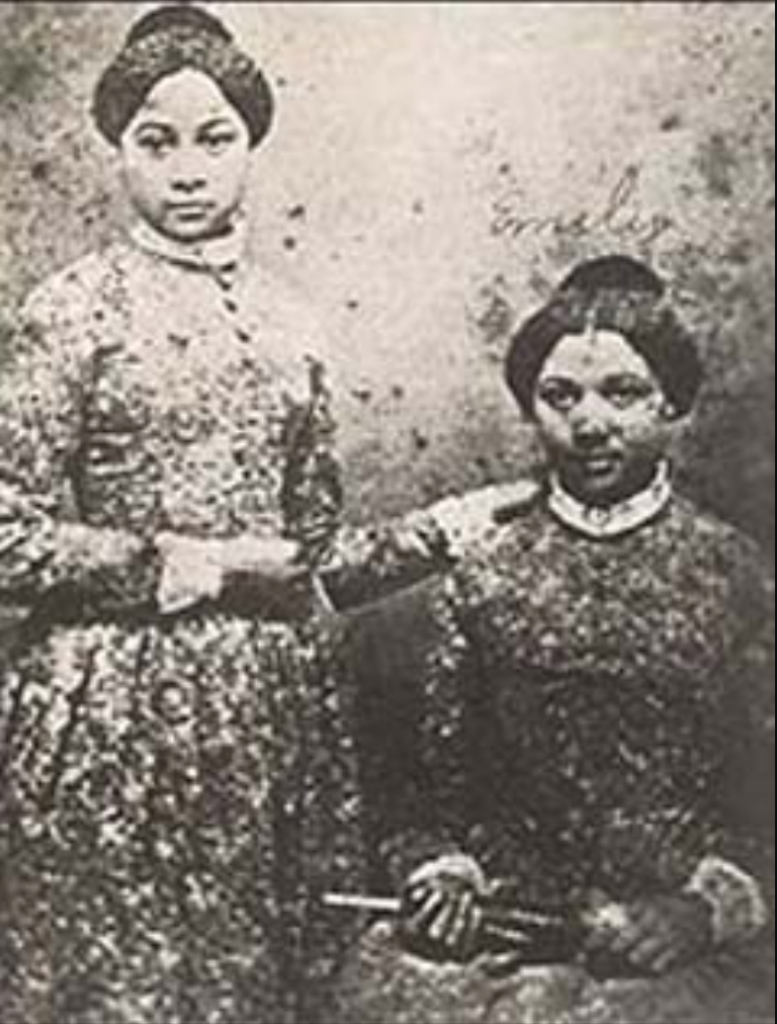

Daniel Bell, a formerly enslaved ironworker, was at the center of a revived Underground Railroad operation in Washington. Bell had worked with Smallwood at the Washington Navy Yard. In 1848, when Bell’s wife, children, and two grandchildren faced sale south, he contacted Daniel Drayton, a semiliterate, white, Delaware Bay trader from southern New Jersey. In turn, Drayton paid Edward Sayres of Philadelphia $100 to charter Sayer’s schooner Pearl to transport slaves to freedom. Chaplin worked with Bell for months thereafter as the number of potential escapees increased.[8]

On Saturday night April 15, 1848, the Pearl, with 77 men, women, and children crowded below deck, and a crew, consisting of Drayton, Sayers, and young white deckhand Chester English, cast off in Washington harbor. They planned to use the Potomac River and the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal to reach Frenchtown, New Jersey. But, as the vessel approached the Potomac’s mouth, the steamer Salem, crewed by 30 well-armed white proslavery volunteers and commanded by a Washington magistrate, overtook and captured the Pearl. The Salem towed the Pearl and those on board back to Washington, where the volunteers marched the ship’s crew and passengers to the city jail.[9]

In response Black residents gathered in the streets, while white antislavery activists provided lawyers for Drayton, Sayers, and English. As Black and antislavery white crowds surrounded the city jail, a proslavery mob, led by local slave traders, confronted them.

That Wednesday slaveholders came to the jail to begin selling the captives south. The antislavery community acted to counter this, purchasing the freedom of some African Americans in imminent danger of sale and of some who had already been taken as far south as New Orleans. But most of the Pearl passengers did not gain freedom. And by June 1848 approximately twenty remained in Washington Jail. Their fate is unknown.[10]

Meanwhile Drayton, Sayres, and English faced trial in Washington, DC on charges of slave stealing and transporting slaves out of the District. Several local lawyers served as the men’s defense. English gained acquittal because he did not know the purpose of the Pearl voyage. Sayres remained in jail, pending payment of a huge fine totaling $10,360 for transporting slaves. Drayton’s case proved to be more dramatic as prosecutors attempted unsuccessfully to force him to reveal the names of those who collaborated with him. In response his defense team argued that because Drayton did not intend to keep the slaves or sell them for profit, he was not guilty of stealing them.

Juries convicted Drayton on two counts of stealing slaves. He initially received a twenty-year penitentiary sentence. Then in the spring of 1849 a new jury found him not guilty of slave stealing. In return he pled guilty to the transportation charges and, like Sayres, received a $10,360 fine, with the same stipulation that he remain in Washington Jail until he paid. The result was that he and Sayres stayed there until President Millard Fillmore pardoned them in August 1852, after intensive lobbying by US Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts,.[11]

Two years earlier, in August 1850, the Washington Guard had arrested Chaplin following a ferocious battle on the District of Columbia-Maryland line as he attempted to transport two escaping slaves northward. After northern abolitionists posted bail for him, he permanently left the city.

Mary and Emily Edmonson were captured during the failed mass escape on the Pearl in 1848 (House Divided Project)

Although a failure, the Pearl escape attempt struck a strategic blow against slavery in Washington and the surrounding states, because it frightened slaveholders regarding the extent of cooperation between African Americans and slavery’s white opponents. One result of that fear, however, was more suffering among local Black families, as sales south increased. It also led to more kidnappings of free Black people as profits for slave-trading companies increased.

Although a failure, the Pearl escape attempt struck a strategic blow against slavery in Washington and the surrounding states, because it frightened slaveholders regarding the extent of cooperation between African Americans and slavery’s white opponents.

As Black families faced these precarious circumstances, bonds between Washington’s Black and antislavery white populations tightened. African Americans went to court and raised funds to purchase freedom. White antislavery activists tracked slave sales, attended slave auctions, visited slave pens, and investigated kidnappings. They worked with endangered Black people to avoid sales south, secure freedom for those who had been arrested as fugitive slaves, and purchase freedom for other enslaved people in the District.[12]

And assisted escapes continued. In 1853 Myrtilla Miner, a white northern woman, who had established a school for Black girls in Washington, helped several Black children escape by placing them with northern families. In 1855 local Underground Railroad activists helped 15-year-old Anna Maria Weems escape with the aid of a white agent sent south by Black Philadelphian Underground Railroad leader William Still. Between 1854 and 1857 Jacob Bigelow, a local white attorney who was originally from Massachusetts, organized group escapes, working with Still and several local black families.[13]

With the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860 and the start of the Civil War in 1861, the status of slavery in Washington began to change. Initially Lincoln pledged to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and was reluctant to move against slavery anywhere in the Border South. Yet almost immediately the Lincoln administration transformed government policy concerning slavery and Black rights in Washington. In April 1862 a Republican-controlled Congress emancipated the slaves in the District of Columbia. One month later it repealed the local black code.[14] Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 and the final Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. In 1864 Congress repealed the fugitive slave laws, and Lincoln successfully pressed Maryland to abolish slavery within its borders.

Even as these changes occurred, Washington’s biracial Underground Railroad continued. Its actions included providing transportation for freed people, or “contrabands” as they were known during wartime, who were threatened with reenslavement. For example, in 1862 the predominantly white National Freedmen’s Relief Association planned “to send a col[ored’ brother to Phil[Adelphia] & N.Y. to obtain a vessel to transport at least 100 Contrabands quietly to the North to get them out of the clutches of southern hounds.” In response to another one of the Freedmen’s Relief Association’s efforts, in June 1863 local constables arrested three women and four children who had escaped into the city from Prince George’s County, Maryland. The following September, slaveholders recaptured a band of 30 enslaved people attempting to escape from the same county.[15] Meanwhile, as the war drew to a close, white abolitionists continued to cooperate with local Black activists in sheltering freedom seekers in their homes. Those Black and white activists who had come before them had set an example with lasting impact.

Further Reading

- Fields, Barbara Jeanne. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland during the Nineteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

- Harrold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Harrold, Stanley. Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press: 2003.

- Pacheco, Josephine F. The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

- Phillips, Christopher. Freedom’s Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860. Urbana: Illinois University Press, 1998.

- Torrey, Fuller. The Martyrdom of Abolitionist Charles Torrey. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

Citations

[1] Joseph C. Lovejoy, Memoir of Rev. Charles T. Torrey, 2nd ed. (1847; reprint New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969); Thomas Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Colored Man) (Toronto: James Stephens, 1851).

[2] Smallwood, Narrative, 17-18.

[3] Samivel Weller Jr. [Smallwood] to Editor, November 19, 1842, in Tocsin of Liberty, December 8, 1842; Smallwood, Narrative, 17-28.

[4][Torrey], “First Annual Report of the Albany Vigilance Committee,” Tocsin of Liberty, December 22, 1842.

[5]Weller to Editor, November 19, 1842, in Tocsin of Liberty, December 8,, 1842; Weller to Printer, April 12, 1843, in Albany Patriot, April 27, 1843; Smallwood, Narrative, 23—28, 30-33, 37-38.

[6]Lovejoy, Torrey, 283; [Chaplin to Albany Patriot, February 3, [1845], February 12, 1845; John F. Cook Sr. to Myrtilla Miner, July 31, 1845, Myrtilla Miner Papers, Library of Congress; “Mark Caesar” and “William ‘Bill’ Wheeler,” Archives of Maryland, MSA SC 5496-0036, 5496-15256.

[7]Chaplin to Gerrit Smith, March 25, 1848, Smith Papers, Syracuse University Library.

[8]True Wesleyan, September 23, 1848; Horace Mann, Slavery: Letters and Speeches (1851; reprint New York: Burt Franklin, 1965), 116-17; National Intelligencer (Washington), April 19, 1848; North Star (Rochester, N.Y.), May 28, 1848.

[9]Daily Union, April 19, 1848; Daily National Intelligencer, April 19, 1848.

[10]E. S. H., editorial correspondence, April 17, 1848, in Daily True Democrat, April 26, 1848; New York Herald, April 21, 1848; Chaplin to Gerrit Smith, November 2, 1848, Smith Papers; Non-Slaveholder 3 (July 1848): 165.

[11]Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton, for Four Years and Four Months a Prisoner (for Charity’s Sake) in Washington Jail (New York: American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 1855), 25-26, 36, 46, 61-69, 99-100, 115-19.

[12]David A. Hall to Salmon P. Chase, June 27, 1848, Chase Papers, Library of Congress; National Era, October 17, 1850.

[13]Samuel Rhoads to Miner, March 17, 1853, Miner Papers; Still, The Underground Railroad (1872; reprint New York: Arno, 1968), 187-89.

[14]National Republican, June 10, 1863; Daily Morning Chronicle (Washington), September 16, 1863.

[15]Danforth B. Nichols to Simeon S. Jocelyn, June 2, 1862, J. R. Johnson to George Whipple, July 4, 1862, American Missionary Association Archives, Amistad Research Center.

Author Profile

STANLEY HARROLD is an emeritus professor of history at South Carolina State University. Harrold received a B.A. in history from Allegheny College, and holds a M.A. and Ph.D. in nineteenth century American history from Kent State University. Harrold received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities for two of his publications. Harrold is a coauthor and coeditor of the world’s bestselling African-American history textbook series, The African-American Odyssey (University Press of Florida). Harrold is also the editor of the high school version of the textbook, Southern Dissent, that consists of 28 books, six of them having won awards. Harrold was awarded with a faculty research award from the National Endowment for the Humanities for his book Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

STANLEY HARROLD is an emeritus professor of history at South Carolina State University. Harrold received a B.A. in history from Allegheny College, and holds a M.A. and Ph.D. in nineteenth century American history from Kent State University. Harrold received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities for two of his publications. Harrold is a coauthor and coeditor of the world’s bestselling African-American history textbook series, The African-American Odyssey (University Press of Florida). Harrold is also the editor of the high school version of the textbook, Southern Dissent, that consists of 28 books, six of them having won awards. Harrold was awarded with a faculty research award from the National Endowment for the Humanities for his book Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).