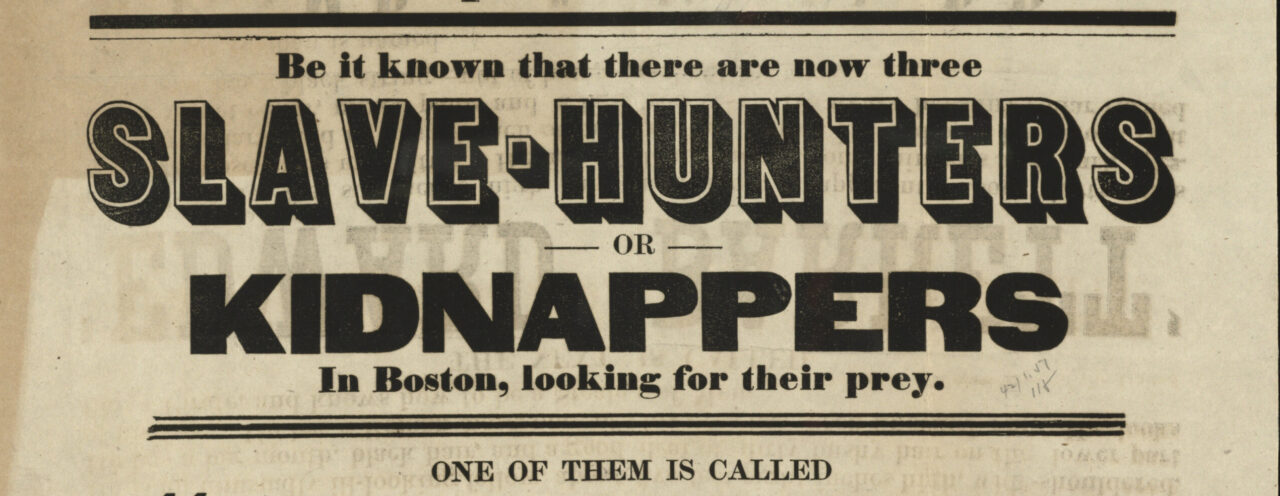

Banner image: Underground Railroad operatives in New England sometimes tried to disrupt slave catchers in this heavily antislavery region through aggressive public exposure (Boston Public Library)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

In mid-October 1850, about a month after President Millard Fillmore signed the Fugitive Slave Act, ten “fugitives from Southern Slavery” issued a call to the people of Northampton, Massachusetts to attend a public meeting for determining “such measures, as they may deem proper to prevent Massachusetts from being made slave hunting ground; the purity of the judiciary form being soiled by legal bribes, and the public Treasury from being robbed to perpetrate these gross and enormous wrongs.”[1] John Williams, who fled from Kentucky slavery by 1845, called the meeting to order. By January 1851, he left Northampton for parts unknown.

It is remarkable that people who had escaped slavery should identify themselves as fugitives, and by name, in the newspapers, especially just a month after the Fugitive Slave Act became law. Only two days after the Northampton meeting, men arrived in Boston to capture and return William and Ellen Craft to slavery in Georgia. The novelty of the Crafts’ 1848 escape—Ellen dressed as a white man with a broken arm and William as the man’s servant—and their evident absence of concern about capture made them instant celebrities on the antislavery lecture circuit. Yet by 1850 their notoriety impelled the secretary of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee to suggest that the Crafts should go to Boston, “as it had then been about a generation since a fugitive had been taken back from the old Bay State.”[2] By August of that year the Crafts moved in with Lewis and Harriet Hayden, who had themselves escaped slavery, at their boarding house on 66 Southac Street, where the federal census also shows five Black male residents originally from slave states. William opened a furniture making and repair shop—and is listed in the 1850 manufacturing schedules of the census—and Ellen began learning upholstery from a “Miss Dean,” a friend of a white couple, George S. and Susan Hillard of 54 (now 62) Pinckney Street. George Hillard was a US commissioner and thus bound by the new law to return freedom seekers to bondage. But it was his wife Susan who told Ellen Craft that her enslaver’s agent was in Boston and had her stay in the couple’s Pinckney Street home while the town’s Black and white abolitionists arranged to move the couple out of the city. [3] Susan Hillard is documented to have sheltered at least five others who had escaped slavery at her home, as her neighbor James Freeman Clark recalled:

My neighbor and friend, Mr. George S. Hillard, was an United States Commissioner. It might be his business after the slave law was passed (1850) to issue a warrant to the marshal for the capture of slaves. But Mrs. Hillard, his wife, was in the habit of putting the fugitives in the upper chamber of their own house, and I think Mr. Hillard was aware of the fact and never interfered. There was once a colored man, a fugitive, put in this upper room, and when Mrs. Hillard went in she found he had carefully pulled down the shades of the window. She told him she did not think there was any danger of his being seen from the street. “Perhaps not, Missis,” he replied, “but I do not want to spoil the place.” He knew that after he had gone, there would be some one else who would need to be protected. He did not want any one to see his colored face there, lest it might excite suspicion, to the injury of his successors.[4]

Of the ten who had signed the Northampton meeting call, six of them lived in “Broughton’s Meadow” (by 1852 the Northampton village of Florence), two lived in Northampton, and two cannot be positively identified, though one may have used an alias in one Northampton newspaper and his given name in the other. Like John Williams, four other signers left town within a few years and have not so far been found elsewhere. But three—Basil Dorsey, Lewis French, and Henry Anthony—remained in or near the village. Dorsey’s 1837 escape from Maryland had been well publicized, like the story of the Crafts, but he lived apparently peaceably in nearby Charlemont for six years before moving to Florence, where he died in 1872. Anthony was probably living in Florence by 1840 and died there in 1880. French, who had worked in the Florence daguerreotype case factory of Alfred Critchlow and stayed there with Critchlow when he learned he was being pursued, married an African American woman and moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he remained through at least 1860.[5]

Acknowledging instances of people escaping slavery and living more or less openly in New England—many such cases are documented—does not minimize the real danger some faced during their northern lives. John W. Thompson, unnerved by renditions in Philadelphia after he had escaped from Maryland in 1842, told the captain of New Bedford whaling bark Milwood that he reckoned a whaling voyage was “the place where I stood least chance of being arrested by slave hunters.”[6] And just as the Crafts were hunted in 1850, Moses Roper’s escape was advertised when he left North Carolina slavery aboard a cattle and lumber schooner from Savannah to New York in 1834. He worked on the New York canals and was going to school in Ludlow, Vermont, when he learned of the advertisement. Roper fled to a “retired place” outside of Ludlow, then to New Hampshire, where he felt unsafe, and finally to Boston, where he attended services at the African Meeting House until he found that “slave-owners were in the habit of going to this colored chapel to look for runaway slaves.” Soon afterward, Roper fled to England and did not return to the United States until after 1861.[7]

Acknowledging instances of people escaping slavery and living more or less openly in New England—many such cases are documented—does not minimize the real danger some faced during their northern lives.

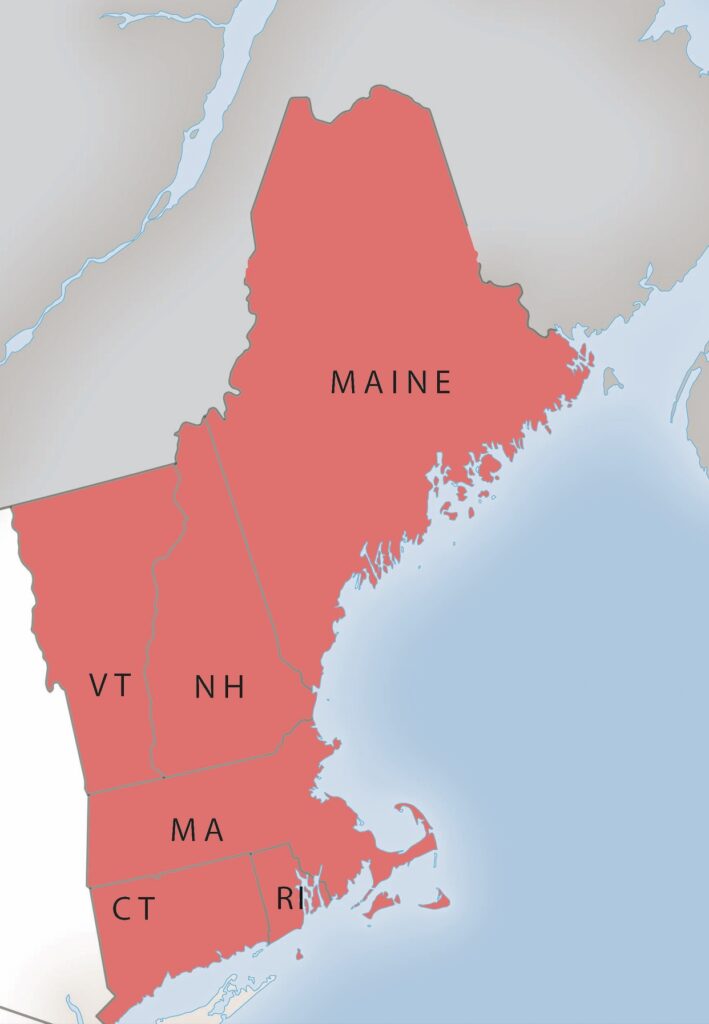

Well-publicized successful and unsuccessful renditions from Boston—George Latimer in 1842, Thomas Sims and Shadrach Minkins in 1851, and Anthony Burns in 1854—created the general impression that those who had fled slavery were everywhere and always in danger. These efforts were threatening enough that in some places African Americans left en masse: a correspondent to the New York Independent reported in 1853, for example, that some 150 left Boston after the Fugitive Slave Act, sixty of them from Leonard Grimes’s Twelfth Baptist Church, even then known as the “fugitive slaves’ church.”[8] Contemporary newspapers and correspondence cite numerous cases of fugitives being pursued into northern New England. Attempted renditions occurred even as far north as St. Albans, Vermont, 16 miles from the Canadian border, despite historians who assert that the absence of commercial connections between Vermont and the South meant “no safer place” existed for freedom seekers.[9] In March 1854 African American minister John W. Lewis reported in Frederick Douglass’ Paper that four fugitives had arrived in that town with the “tyrants . . . close on their track,” and local abolitionists promptly “had an express train under way” to take them into Canada. In May 1856 an enslaver and a federal marshal arrived in St. Albans to retake an unnamed fugitive who had escaped from Baltimore in January and had been working for several months for the cattle and sheep breeder Alanson M. Clark. “On making inquiry of the object of their pursuit, they were kindly informed that they would be more successful in securing the prize at Waterbury, Vt., than at St. Albans,” the St. Albans Messenger reported. “Meantime the friends of the ‘colored brother’ transported him a few miles further north in a sleigh and placed him in a freight train, and in a few hours he was beyond the reach of the U. S. Marshall safe on British ground.”[10] John W. Lewis reported in August 1854: “During the last winter, spring, and this summer, we have had companies of two and four at a time, arriving in St. Albans, and leaving for Canada. In no instance do our citizens let them lack for substantial means for their comfort. And such is the feeling of that whole community, a kidnapper would endanger his life to attempt an arrest. ‘Resistance to tyrants in obedience to God,’ is the motto of all.’”[11] Vermont newspapers and other accounts document numerous chance encounters between freedom seekers and their enslavers or others who had known them in the South.

The Hayden boardinghouse in Boston is now part of the Network to Freedom ( NPS)

Yet it is likely the case that many more people who had escaped slavery lived without direct threat from enslavers and their agents than were pursued into northern places. Historian Stanley W. Campbell noted that no fugitives were returned to slavery from New England after the Burns rendition. The Fugitive Slave Act was a “dead letter” in New England “not because the law could not be enforced; it was because it was not economically feasible to trace, capture, and return fugitive slaves from there. In fact, it never had been.”[12] In addition to the sheer expense of the endeavor, Campbell suggested, New England personal liberty laws and “hostile public opinion” also kept pursuit at a low level. Armed African Americans barricaded themselves in Lewis Hayden’s Boston home to prevent the seizure of William Craft. A reported 20 African American men stormed a Boston courthouse to rescue Shadrach Minkins. The escape of Edinbur Randall from Jacksonville, Florida, on the lumber bark Franklin in 1854, and the efforts of the vessel’s captain to return him to slavery, triggered several aggressive countermeasures. Upon his escape to Martha’s Vineyard, Randall received help from one Gay Head Indian woman who hid him in her attic and “declared that she would have a large kettle of hot water ready to scald the sheriff, or any of his understrappers, who crossed her threshold.” A group of Indians, African Americans, and Afro Indians “armed with guns, pitchforks, clubs, and almost anything that would do to fight with” gathered on shore to prevent anyone from stopping two Indian men from rowing Randall to the mainland. Unaware of this action, the Boston Vigilance Committee sent one of its own to Bath, Maine, the Franklin’s destination, to help organize a local committee to board the vessel and take Randall. But Randall, according to Beulah Vanderhoop, the Gay Head Indian who had engineered his removal from the Vineyard, spent the next seven years “working about wharves” in New Bedford under the alias Edgar Jones.[13]

In New England, fugitive populations were generally largest in the port cities with greater populations of color, the opportunity for work both aboard and on shore, and robust abolitionist sentiment and activity. That would embrace New Bedford, Boston, and Springfield in Massachusetts; Providence and Newport in Rhode Island; Hartford and New London in Connecticut; Portland, Maine; and Burlington, Vermont. In such places, freedom seekers could and did disappear into waterfront districts crowded with people of color and transients or into African American neighborhoods that many law officers either tended to avoid or knew little about. The largely African American north slope of Boston’s Beacon Hill, for example, featured an intricate array of alleys, courts, and enclaves that were virtually invisible to people who did not live in the neighborhood.

The dynamic in rural areas was the opposite of the port cities. In rural areas, the more remote the area the better, as long as at least some active sympathizers were present. Unitarian cleric Joshua Young, a fugitive assistant in Boston and Burlington, Vermont, defined the Underground Railroad as “simply the aiding and passing on from one well known and trusty agent to another, of the fugitives on their way to Canada” chiefly by “helping the fugitive in avoiding the central and more public places on his route to Freedom.” Florence was a fugitive “haven” because it was the home in the 1840s to the Northampton Association of Industry and Education, the only known communal experiment to have formally embraced racial equity. In 1847 the Boston Vigilance Committee sent Josiah Thomas, his wife, and their child to Ashburnham, Massachusetts, and asked thread spool manufacturers Gilman Jones and Enoch Whittemore to give Thomas work and shelter the family. The Thomases remained in that town through at least 1860. James Lindsay Smith escaped from Virginia in 1838 to Philadelphia and then New York, where African American abolitionist David Ruggles sent him through Hartford and to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he was told to “make yourself at home.” Thomas worked at Rufus Elmore’s wholesale shoe shop for a year, lectured on the antislavery circuit, and moved in 1842 to Norwich, Connecticut (David Ruggles’s birthplace), where he was a minister and shoemaker until he died in December 1884.[14]

Even as abolitionists were a distinct minority of the regional population, a significant number held positions of importance in their communities, which sometimes presented a formidable obstacle to enslavers and their agents. In 1838 Chauncey L. Knapp was Vermont’s secretary of state when he drove to the home of sheep farmer Rowland T. Robinson in Ferrisburg to bring the Virginia fugitive Charles Nelson to Montpelier. “The lad (Charles) is now sitting in my office in the State House,” Knapp wrote to an assistant in Saratoga, and Knapp set about looking for a home, a school, and an apprenticeship for Nelson. For his part, Robinson is said to have sheltered “scores” of fugitives and is documented to have employed several; his home, Rokeby, is now the site of Vermont’s only permanent Underground Railroad exhibition.[15] Lawrence Brainerd of St. Albans was a US senator and a major investor in Lake Champlain steamboats and, after 1850, the Vermont and Canada Railroad. According to his son, he used both conveyances to move fugitives north.

Rokeby Museum in Vermont (Rokeby)

Brainerd was far from the only vessel and railroad investor to help freedom seekers, and the role he, others similarly situated, and transport employees played in the movement of fugitives deserves thorough investigation. Erastus Hopkins of Northampton and Springfield, Massachusetts, was the president of the Connecticut River Railroad and Seth Hunt of Northampton, the company clerk. Both assisted fugitives and used the Underground Railroad to do so. In 1859 Hopkins wrote to his nephew that though he had retired from the “above ground railroad….for the first time I act as Prest. of the Underground Railroad.” Brown Thurston, a printer in Portland, Maine, stated that he conveyed fugitives to Canada by coasting vessels and the Grand Trunk Railroad, which charged half-fare or no fare at all. Elizabeth Buffum Chace conveyed fugitives from her Valley Falls, Rhode Island, home to the Providence and Worcester Railroad, where a conductor received them and assured that they transferred “to the Vermont road, from which by … arrangement, they were received by a Unitarian clergyman named Young, and sent by him on to Canada, where they uniformly arrived safely.” William Ingersoll Bowditch sent fugitives from Boston to the Newton home of William Jackson, a farmer and prominent railroad promoter, builder, and agent from 1826 to 1847. “His house being on the Worcester Railroad, he could easily forward any one,” Bowditch later wrote.[16]

Much as railroads, rivers, and canals were significant in the passage of people who escaped slavery, the means of their passage through, or settlement in, urban and rural New England places were multiple, multifaceted, “as various as the instances of rescue,” Joshua Young pointed out. “The Abolitionists of New England were pretty well known to each other, at least, by name and residence, through their contributions to the cause of anti-slavery, and their being subscribers to the Liberator, Mr. Garrison’s paper,” Young stated, “and it was sufficient to inform one another of what was going on” to make the Underground Railroad a functioning feature of antebellum New England life.[17]

Further Reading

- Bartlett, Irving H. “Abolitionists, Fugitives, and Imposters in Boston, 1846-47,” New England Quarterly 55, 1 (March 1982): 97-110.

- Boston Public Library Anti-Slavery Collection. https://archive.org/details/bplscas

- Still, William. The Underground Railroad. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872.

- Wilbur H. Siebert Underground Railroad Collection. Ohio Memory Connection. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/siebert/

- Zirblis, Raymond Paul. “Friends of Freedom: The Vermont Underground Railroad Survey Report.” Montpelier, VT: Vermont Department of State Buildings and Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, 12 December 1996.

Citations

[1] “To the Citizens of Northampton,” Hampshire Gazette, October 15, 1850, and Northampton Courier, October 20, 1850.

[2] William Still, The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., Narrative the Hardships Hair-breadth Escapes and Deaths Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom, as Relation by Themselves and Others, or Witnessed by the Author (1871; reprint, Chicago: Johnson Publishing Co., 1970), 384.

[3] Still, Underground Railroad, 387-88.

[4] James S. Freeman Clark, Antislavery Days (New York: John W. Lowell, 1883), 83.

[5] See Kathryn Grover, “African Americans, Abolition, and Reform in Northampton, Massachusetts, 1820-1900: Statement of Historic Context” (Northampton, MA: David Ruggles Center for History and Education and Committee for Northampton, January 2021), National Register Historic District nomination for Florence, (2021) and Dorsey-Jones House, National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom (2009), David Ruggles Center, Florence, MA.

[6] The Life of John Thompson, a Fugitive Slave, Containing His History of 25 Years in Bondage, and His Providential Escape. Written By Himself (Worcester, MA: John Thompson, 1856), 103, 107-8.

[7] A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American Slavery (Philadelphia: Merrihew and Gunn, 1838); see also Roper’s documented Wikipedia entry.

[8] “The Colored Population of Boston,” Pennsylvania Freeman, August 25, 1853, from the New York Independent. See also Fred Landon, “The Negro Migration to Canada after the Passing of the Fugitive Slave Act,” Journal of Negro History 5, 1 (January 1920): 22-36.

[9] R. L. Morrow, “The Liberty Party in Vermont,” New England Quarterly 2, 2 (April 1929): 234-48, 234. Morrow’s assertions about Vermont were repeated almost verbatim in Wilbur H. Siebert, Vermont’s Anti-Slavery and Underground Railroad Record (Columbus, OH: Spahn and Glenn, 1937), 23.

[10] “Escape of a Fugitive Slave,” St. Albans Messenger, April 24, 1856. Lawrence Brainerd, probably St. Albans’s most active white abolitionist, may have had something to do with the fugitive’s employment, as Clark had once clerked for Brainerd. as well as with his flight further north.

[11] “Letter from J. W. Lewis,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, August 25, 1854. Lewis lived in St. Albans from at least June 1853 probably until 1858 or 1859; he died in Haiti in 1862 after having shepherded a group of African Americans there to settle.

[12] Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 185.

[13] New Bedford Standard, September 29, 30, 1854; Francis Jackson, “Fugitive Slaves,” The Liberty Bell. By Friends of Freedom (Boston: National Anti-Slavery Bazaar, 1858): 29-43; Netta Vanderhoop, “The True Story of a Fugitive Slave: Or the Story a Gay Head Grandmother Told,” Vineyard Gazette, February 3, 1921. Jackson’s account does not mention the armed party. New Bedford censuses do not record Jones under this name, Edinbur Randall, or John Mason, another alias he used.

[14] Irving H. Bartlett, “Abolitionists, Fugitives, and Imposters in Boston, 1846-47,” New England Quarterly 55, 1 (March 1982): 102-3; Jody Fernald and Stephanie Gilbert, “Oliver Cromwell Gilbert: A Life,” University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository, 2014, https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1074&context=library_pub;

James Lindsay Smith, Autobiography of James L. Smith. (Norwich, CT: Press of the Bulletin Company, 1881).

[15] Raymond Paul Zirblis, “Friends of Freedom: The Vermont Underground Railroad Survey Report” (Montpelier, VT: Vermont Department of State Buildings and Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, 12 December 1996), 40, and “Anti-Slavery Action in 1838: A Letter from Vermont’s Secretary of State,” Vermont History 5, 41 (1973): 7-8O. On Robinson, see Allan S. Everest, ed., Recollections (Plattsburgh, NY: Clinton County Historical Association, 1964), 58, cited in Tom Calarco, “The Fresh Air of Freedom: The Underground Railroad in Vermont” (Paper, n.d.), 4, 32 n.6.

[16] Erastus Hopkins to John B. Wheeler, July 11, 1859, cited in Bruce Laurie, Rebels in Paradise: Sketches of Northampton Abolitionists (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 140-41, 170 n. 64; Thurston’s obituary in the Eastern Argus, April 25, 1900, cited in H. H. Price and Gerald E. Talbot, Maine’s Visible Black History: The First Chronicle of Its People (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House, 2006), 255-56; Elizabeth Buffum Chace, “My Anti-Slavery Reminiscences” (Valley Falls, R.I., 1891) in Two Quaker Sisters from the Original Diaries of Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lucy Buffum Lovell (New York: Liveright Publishing Corp., 1937), 127-28; William I. Bowditch to Wilbur Henry Siebert, 5 April 1893, vol. 1, “The ‘Underground Railroad’ in Massachusetts,” Material Collected by Professor Wilbur H. Siebert, Ohio State University, Columbus, n.d., Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[17] Joshua Young to Wilbur Henry Siebert, April 21, 1893, Wilbur H. Siebert Underground Railroad Collection, available online from Ohio History Connection, https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/siebert/id/24691

Author Profile

KATHRYN GROVER is an independent researcher, writer, and editor in American social, ethnic, and local history. Grover’s publications include: Make A Way Somehow: African American Life in a Northern Community (Syracuse University Press, 1994); The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (University of Massachusetts Press, 2001) Rochester, New Hampshire, 1890–2010: “A Compact Little Industrial City” (Peter E. Randall, 2013); The Brickyard: The Life, Death, and Legend of an Urban Neighborhood (Lynna Museum and Historical Society, 2004). She is editor of New Jersey History of the New Jersey Historical Society. Grover has also published a Historic Resource Study of the antebellum African American community on the north slope of Beacon Hill for Boston African American National Historic Site.

KATHRYN GROVER is an independent researcher, writer, and editor in American social, ethnic, and local history. Grover’s publications include: Make A Way Somehow: African American Life in a Northern Community (Syracuse University Press, 1994); The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (University of Massachusetts Press, 2001) Rochester, New Hampshire, 1890–2010: “A Compact Little Industrial City” (Peter E. Randall, 2013); The Brickyard: The Life, Death, and Legend of an Urban Neighborhood (Lynna Museum and Historical Society, 2004). She is editor of New Jersey History of the New Jersey Historical Society. Grover has also published a Historic Resource Study of the antebellum African American community on the north slope of Beacon Hill for Boston African American National Historic Site.