Banner image: The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center in Church Creek, Maryland hosts the program office for the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, National Park Service (NPS)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

Frederick Douglass, 1855 (House Divided Project)

Of all the horrors of slavery, the cruelest was its effect on the spirit of the enslaved. Frederick Douglass, who escaped in 1838 and became an Underground Railroad operative and leading anti-slavery orator, described a period of his enslavement when he became a field hand hired to a notorious “slave breaker.” In his account, Douglass acknowledged that after a few months “I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished…the dark night of slavery closed in upon me.”[1] Abolitionist Wendell Phillips, in a letter to Douglass published as a preface to the autobiography, lauded him for describing the wretchedness of slavery by the “cruel and blighting death which gathers over his soul” rather than by the hunger, toil, and punishment which the enslaved endured.[2]

John Parker was born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia in 1827. At the age of eight, he was sold on a slave block and forced to walk to Mobile, Alabama. After several unsuccessful escape attempts, he was able to purchase his freedom when he was 18. Parker settled in Ripley, Ohio on the banks of the Ohio River where he actively assisted freedom seekers. Reflecting on his life, Parker observed:

I soon learned that there was not so much brutality in slavery as one might expect. It was an incident to the curse, but the real injury was the making of a human being an animal without hope. Now that it is all over, as I have previously stated, I know slavery’s curse was not pain of the body, but the pain of the soul.[3]

The John P. Parker House in Ripley, Ohio is part of the Network to Freedom (NPS)

The humanity of enslaved individuals is central to understanding the resistance movement known as the Underground Railroad. When Calvin Fairbank asked Lewis Hayden why he wanted to be free, Hayden replied “Because I’m a man.” Freedom seekers were at the center of the Underground Railroad, for without self-liberators, there would have been no Underground Railroad. While allies were critical to its success, the central story of the Underground Railroad concerns resistance to enslavement through escape and flight. Freedom seekers had to overcome the soul-destroying nature of enslavement to self-liberate. They often had to leave behind family and everyone they knew and loved. While several factors could precipitate self-liberation, it was the compelling need for freedom and self-determination that sustained freedom seekers.

This is the history that the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom seeks to unravel. The movement, both historically and contemporaneously, was a grassroots effort. The threads of these stories have remained alive in the accounts passed through the generations. Modern efforts by descendants and communities to preserve and share their stories led to legislation creating the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom (NTF) Program within the National Park Service in 1998. The legislation identifies the Underground Railroad as one of the most significant expressions of the American civil rights movement. The NTF commemorates, honors, and interprets the history of the Underground Railroad, extols the historical significance of the Underground Railroad in the eradication of slavery and highlights its relevance in fostering the spirit of racial harmony and national reconciliation.

Through its mission the NTF helps to advance the idea that all human beings embrace the right to self-determination and freedom from oppression.

Through its mission the NTF helps to advance the idea that all human beings embrace the right to self-determination and freedom from oppression. The NTF is a community engagement program that coordinates preservation and education efforts nationwide. By empowering communities to tell their own history, the NTF is working to integrate local historical sites, museums, and interpretive programs associated with the Underground Railroad into a mosaic of community, regional, and national stories. NPS owns neither the resources associated with this movement, nor the stories that it seeks to share. The federal role in this collaborative effort is threefold. First, NPS is directed to educate the public about the significance and history of the Underground Railroad. We accomplish this primarily through our website, though presentations at conferences and symposia, and through brochures. Second, NPS provides technical assistance to community partners as well as state and local governments who are involved with Underground Railroad history. This function involves NTF staff in a range of projects including research, documentation, historic preservation, curation of artifacts and documents, developing interpretive materials and exhibits, connecting with heritage tourism and economic development initiatives, and capacity building for small non-profit organizations. Third, NPS maintains an evaluated list of historic sites, interpretive and educational programs, and interpretive and educational facilities with a verifiable connection to the Underground Railroad. Once accepted for inclusion in the Network to Freedom, members may use the program’s unique logo on their markers, websites, and publications. This professional, independent validation is often critical to the survival and success of struggling historic sites or interpretive programs and facilities.

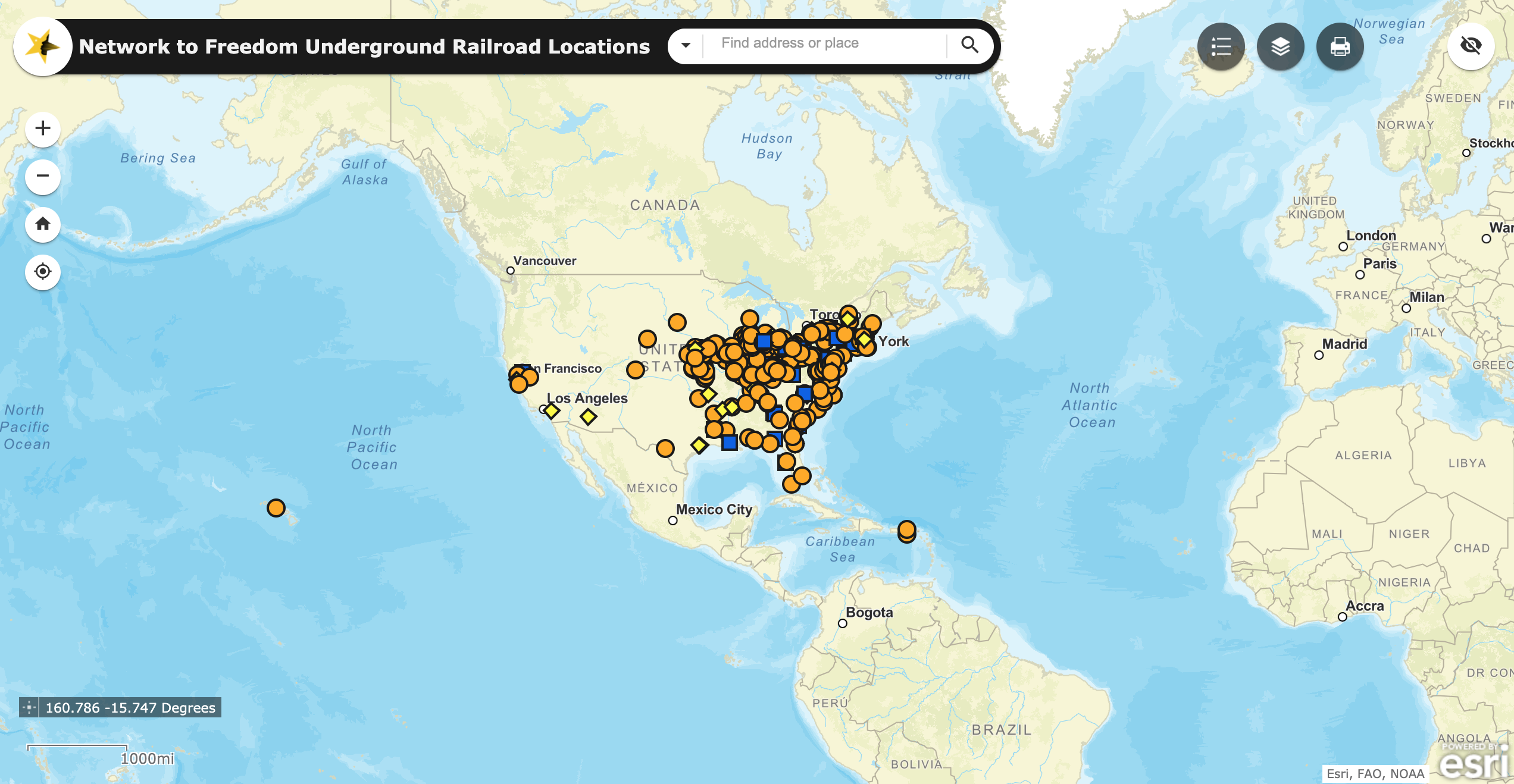

The NTF and its many partners function as a large public history project which has documented hundreds of sites and stories. Collectively, these local stories reveal a complex freedom movement that spanned decades, continents, and oceans, incorporating people of diverse races, religions, social classes, gender, and ethnicities. The NTF includes over 700 members across thirty-nine states, DC, and the Virgin Islands. Please visit the NTF website (www.nps.gov/ugrr) for information about these stories and resources about the history of the Underground Railroad.

Scholarship on Underground Railroad topics has blossomed since the NTF was created in 1998. In recognition of this, and to commemorate our 25th anniversary, the NTF initiated an update to the Underground Railroad handbook that the National Park Service first issued in 1998. Through the leadership of editor Matthew Pinsker, we have gathered essays from nearly two dozen leading scholars. These thematic and geographic essays represent a new understanding of the complexity of the Underground Railroad and the agency of the African American community.

A Note on the Language of Slavery

Language matters when we are talking about the complicated history related to slavery, freedom, and the Underground Railroad. Using the most accurate and respectful language is important, both to the NTF and the National Park Service. The discussion of what language is most appropriate to use, however, is constantly evolving as we learn more information and gain further perspectives. Because of the importance of this ongoing conversation, the NTF and others across the National Park Service are working together to discuss the question of language connected to slavery and freedom.

Many labels for African Americans were constructs of the enslaving society or by paternalistic abolitionists. As such, terms discussing slavery and freedom from the period tend to reflect how the dominant society viewed African Americans and their efforts toward freedom. Instead, the National Park Service and its partners strive to use language that more accurately reflects both the inherent humanity of enslaved people and historical accuracy.

There is not universal consensus on what words are most appropriate to use when talking about slavery. Many people prefer to use the term “enslaved” rather than “slave.” Referring to an “enslaved person” highlights their humanity rather than the socially constructed status of “slave.” Others focus on the language that was used in historic documents and use the term slave. Some historians prefer to use words like “fugitive” to emphasize that when freedom seekers liberated themselves, they simultaneously broke state and/or federal laws. Others prefer “freedom seeker” in contrast to “fugitive” which carries the stigma of criminality, feeling that it unfairly maligns those seeking freedom through escape, or that it legitimizes the perspective of the society that upheld the legality of slavery.

Citations

[1] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself, (Anchor Books edition; Boston: Anti-Slavery Society, 1845), 66.

[2] Douglass, xxii.

[3] John P. Parker, edited by Stuart Seely Sprague, His Promised Land: The Autobiography of John P. Parker, Former Slave and Conductor of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 26.

Author Profile

DIANE MILLER served as the national program manager for the National Park Service, National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom from 1999 to 2023. Diane began her career at the NPS in 1984 working in the National Register of Historic Places programs. She received her MA in History from the University of Maryland and BA in both History and Anthropology from Ohio University. In December 2019 she received her Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Her dissertation is “Wyandot, Shawnee, and African American Resistance to Slavery in Ohio and Kansas.”

DIANE MILLER served as the national program manager for the National Park Service, National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom from 1999 to 2023. Diane began her career at the NPS in 1984 working in the National Register of Historic Places programs. She received her MA in History from the University of Maryland and BA in both History and Anthropology from Ohio University. In December 2019 she received her Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Her dissertation is “Wyandot, Shawnee, and African American Resistance to Slavery in Ohio and Kansas.”