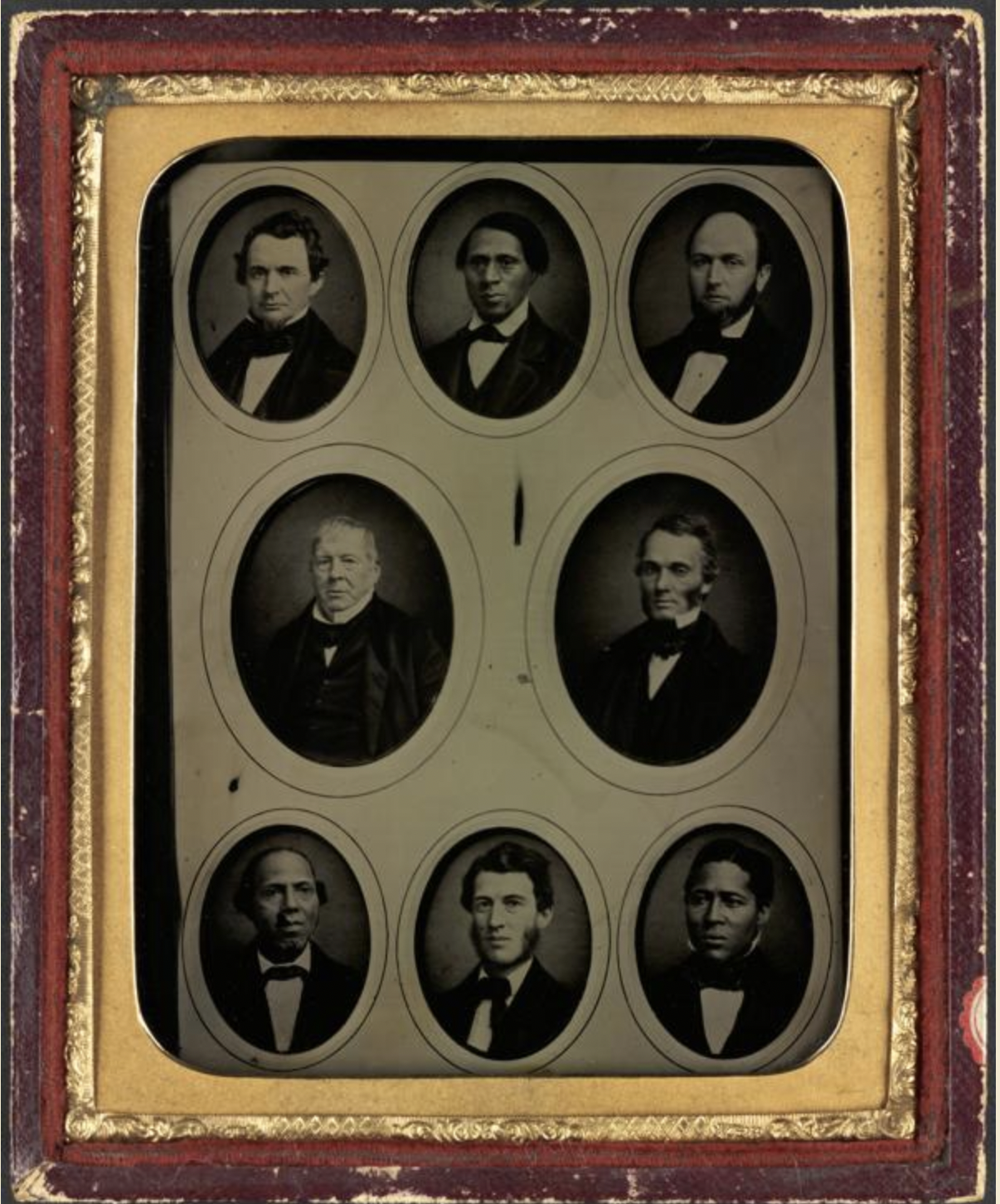

Banner image: Black abolitionists like Robert Purvis (right) and their white allies such as Thomas Garrett (left) aided freedom seekers by leading vigilance committees in Philadelphia and other Northern cities (Boston Public Library)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

The significance of what is popularly called the Underground Railroad in the making of abolition and the sectional conflict cannot be overstated. William Lloyd Garrison called runaways and rebels “self-emancipated” slaves, rejecting the term fugitive as criminalizing freedom-seeking enslaved people.[1] Slaves voted against slavery with their feet and abolitionists assisted them from the earliest days of the republic. Over the years the abolitionist underground grew into a fairly organized system of vigilance committees, safe houses, and antislavery lawyers and politicians, who took fugitive slave cases into northern state and court houses. Runaways gave abolition its most enduring issue, the fugitive slave controversy, and its most dynamic exponents, fugitive slave abolitionists. The impact of the abolitionist underground on national and even international politics is undeniable.

The history of the Underground Railroad must rise above the story of heroic individuals or events dismissed as the stuff of myth and memory. It must be placed in its proper historical context: the growth of the abolition movement. Outstanding Quakers, Isaac T. Hopper, Levi Coffin, and the Presbyterian minister John Rankin, whose careers bridge the two waves of abolition, made assistance to runaways a quintessential form of activism. As a member of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, Hopper became widely known as “the friend and legal adviser of colored people upon all emergencies.”[2] He moved to New York City, where he worked with the Black abolitionist David Ruggles in the New York Committee of Vigilance. Coffin, who moved from North Carolina to Indiana and then to Cincinnati, was known as the “President of the Underground Railroad.” Rankin’s hilltop home in Ripley became a beacon to slaves fleeing across the Ohio River from Kentucky and points further south. Both Coffin and Rankin relied mainly on free Blacks like John Hudson, who ferried runaways across the river, and John Parker, a fugitive slave, who described his encounters with slaveholders in military terms.

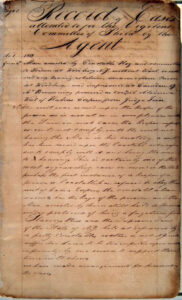

Black barber Jacob C. White maintained the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee’s minute book (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Black abolitionists helped establish the permanent, organizational apparatus of the abolitionist underground, the vigilance committees of the 1830s. At personal risk, Ruggles confronted slave catchers and the kidnapping club in New York that consisted of local officials and law enforcement. The 1837 case of Basil Dorsey led to the founding of the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee by Robert Purvis and other abolitionists. Its most active member was a Black barber, Jacob C. White, whose meticulous “Minute Book of the Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia,” still survives. Other Black abolitionists such as Jermain Loguen in Syracuse, Stephen and Harriet Myers of Albany, Thomas and Frances Brown of Pittsburgh, John and Mary Jones in Chicago, and Lewis and Harriet Hayden in Boston were mainstays of vigilance committees. In 1852, James McKim and Robert Purvis reorganized the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Its secretary William Still later published the stories of the runaways it assisted during the 1850s in The Underground Railroad (1872). Detroit’s Colored Vigilant Committee also acted as an emigration society and soon these committees spread to Canada among fugitive slave communities. In New York City, Sydney Howard Gay editor of the Garrisonian National Anti Slavery Standard kept a two-volume Record of Fugitives, for those whom he had assisted. The central figure in his operations was a remarkable Black man named Louis Napoleon, who did most of the dangerous street work and transporting of runaways.

The abolitionist underground consisted not so much of the elaborate routes mapped by the historian Wilbur Seibert in the 1890s but of distinct sites of activist interracial abolitionism and antislavery politics, like parts of Ohio, the port towns of New Bedford and Boston, south central Pennsylvania and Philadelphia, Detroit, western Illinois and Chicago, upstate New York and New York City, and the area around the District of Columbia. Free Black communities, especially in the racially hostile northwestern states and border slave states, were essential to the social geography of fugitive slave resistance.

Abolitionists did not parse out the difference between slave escapes, kidnapping of free African Americans, or slaveholders in transit with their slaves in free states. Their aim was to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter through legal means or by direct action. In 1836, a group of Black women stormed a Boston courtroom to rescue two enslaved women, who were apprehended after being freed on a writ of habeas corpus brought by Samuel Sewall and the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS). That year in another case brought by the BFASS, Commonwealth v. Aves, Massachusetts Supreme Court chief justice Lemuel Shaw denied slaveholders the right of transit with their slaves through Massachusetts. Citing the 1772 British case, Somerset v. Stuart, Ellis Gray Loring and his co-counsel Rufus Choate established the freedom principle in the commonwealth. In 1837, attorney Salmon P. Chase used the same argument to prevent the rendition of Matilda Lawrence, who was employed by the abolitionist James Birney. Chase lost the case but fought many others that effectively nullified slaveholders’ right of transit in Ohio. He became known as the “attorney general of fugitive slaves” and Cincinnati’s Black community presented him with a silver pitcher for his “eloquent advocacy of the rights of man.”[3] In New York and New Jersey, abolitionist lawyer Alvan Stewart also used writs of habeas corpus to free runaways and hinder their rendition.

Abolitionists did not parse out the difference between slave escapes, kidnapping of free African Americans, or slaveholders in transit with their slaves in free states. Their aim was to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter through legal means or by direct action.

Abolitionist efforts to release freedom seeker George Latimer resulted in the groundbreaking Massachusetts “Latimer Law” (NYPL)

All these men became founding members of the abolitionist Liberty Party, a precursor to the Free Soil and antislavery Republican parties. Abolitionist activism had an impact on northern state laws. In the 1820s, Pennsylvania and New York passed personal liberty laws that granted suspected runaways certain legal protections. In 1839, Governor William H. Seward refused to extradite three Black seamen involved in a fugitive slave rescue from New York to Virginia, just as Maine had been defying a similar extradition request from Georgia for two men accused of assisting runaways two years earlier. In 1840, petition campaigns by abolitionists and the state’s black conventions led to the passage of a New York law granting fugitive slaves trial by jury and repealing its nine-month transit law that allowed slaveholders to reside with their slaves. In a setback for abolitionists, Ohio Democrats passed a state fugitive slave law at the request of Kentucky, ironically a testament to the effectiveness of the Underground Railroad. In the 1842 case Prigg v. Pennsylvania, the Supreme Court outlawed not only all the personal liberty laws but also Ohio’s fugitive slave law. That year abolitionists launched a massive campaign to free George Latimer, who was arrested as a fugitive slave in Boston. They not only managed to purchase Latimer’s freedom but presented the “Great Massachusetts” petition to the General Court asking for a new personal liberty law that would prevent state officials and the use of state jails in fugitive slave rendition in accordance with Prigg. Massachusetts’ Latimer law did precisely that and in 1847, Pennsylvania passed a similar law.

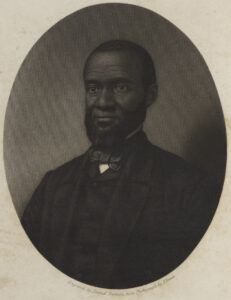

Abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet (National Portrait Gallery)

Unprecedented cooperation between Garrisonians and Liberty Party men in the Latimer case reveals how the Underground Railroad united abolitionists, who were by then divided between political abolitionists and the followers of Garrison who had rejected converting the abolition movement into a political party. Their main constituency became the enslaved themselves as freedom seekers radicalized abolitionist discourse and practice. In 1842, Libertyite Gerrit Smith issued an “address to the slaves” inspired by “the rapid multiplication of escapes from the house of bondage.” He encouraged the enslaved to escape, steal provisions to sustain themselves, and asked abolitionists to assist them. Garrison, caricatured as a moral suasionist, also issued an address to the slaves in 1843, encouraging flight to destabilize slavery. He too was inspired by “twenty thousand of your number [who] have successfully runaway.” That year Black abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet, whose family had escaped slavery when he was but a child, issued the most radical “Address to the Slaves.” He did not encourage running away but called for what can only be described as a general strike. The enslaved should cease laboring for enslavers, even if that provoked rebellion. As he concluded, “Let your motto be RESISTANCE! RESISTANCE! RESISTANCE!”[4]

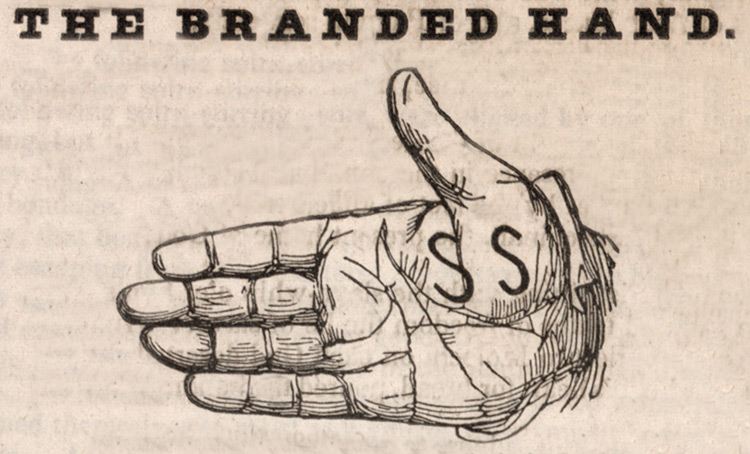

The confrontation with enslavers reached a new level when abolitionists started going into slave states to “run off” slaves. These men and women were Harriet Tubman’s forerunners but few eluded capture, unlike the Moses of her people. Unprotected by law or public opinion, abolitionists who went south became subject to southern laws of slavery in the same manner that self-emancipated slaves who made their way north benefitted from the laws of freedom. In 1841, George Thompson, Alanson Work, and James Burr were arrested, imprisoned, and whipped in a Missouri prison for planning a slave escape. In 1844, Massachusetts sea captain Jonathan Walker, who with the enslaved Charles Johnson attempted to sail with seven runaways was imprisoned, put in a pillory, and had his hand branded with “SS” for slave stealer. Walker became popular on the lecture circuit displaying his branded hand. John L. Brown of Maine was convicted the same year for helping an enslaved woman in Charleston, South Carolina. His death sentence was commuted to a public whipping. Charles T. Torrey, active in the abolitionist underground in the Washington, DC region, was imprisoned in Baltimore for helping a slave mother and her children to escape. He died of tuberculosis in prison. Torrey’s network included African Americans like Thomas Smallwood who escaped to Canada and left a memoir of the Underground Railroad. Incarcerated abolitionists became international cause celebres, with their cases being pleaded and funds raised across the Atlantic.

The branding of Jonathan Walker as a “slave stealer” fueled abolitionism in the 1840s (House Divided Project)

Running off slaves was risky business. In 1848, the Quaker Richard Dillingham was arrested in Nashville and sentenced to three years hard labor. He died in prison of cholera. Calvin Fairbank and a Vermont schoolteacher Delia Webster were arrested in Kentucky for assisting enslaved runaways. One of them was Lewis Hayden. Fairbank was pardoned in 1849 but returned to help another enslaved woman and was arrested again. He was released only in 1864 during the Civil War after suffering from years of solitary confinement, a harsh labor regimen, and regular whippings. John Blevens, incarcerated in a Virginia penitentiary for helping runaways, was released only with the fall of Richmond at the end of the war. Webster returned to Kentucky and ran a farm suspected of harboring fugitive slaves. She was arrested again in 1854 but managed to escape from her besotted jailer to Indiana where an irate crowd ran him out.

Women in the female abolitionist societies harbored, sewed clothes for, and provided food for runaways. But Webster and Laura Haviland from Michigan took women’s activism in the underground a notch further. Like Webster, Haviland traveled to Kentucky and Arkansas, apparently even staring down bloodhounds once, to spirit away slaves and escort them. The state of Tennessee put a price of $3,000 dollars on her head for foiling the recapture of an enslaved woman. Tubman, a self-emancipated slave herself, rescued 70 enslaved people in her 13 trips funded by leading abolitionists.

Fugitive slave escapes became more common, involving groups of runaways who at times fought back, anticipating their momentous actions during the Civil War. At times these escapes resembled mini slave rebellions, with pitched battles between “freedom seekers” and their sympathizers, including free Blacks, abolitionists, bystanders, and employers, and law enforcement authorities, slaveholders, and their agents. In 1848 around 70 slaves escaped to the Ohio river with E.J. “Patrick” Doyle, a student from Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. Apprehended by hundreds of armed white men they fought a gun battle before surrendering. Authorities executed three freedom seekers and sentenced Doyle to 20 years in prison, where he died. Such incidents happened often enough to constitute a “border war” over slavery in the slave and free states that adjoined each other. Episodic clashes over runaways disrupted the proslavery consensus based on commercial and political ties in slavery’s borderlands.

Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia to the Edmonson sisters, freedom seekers who attempted to escape aboard the Pearl in 1848 (Wikipedia)

Slaveholding authorities tried to permanently disable the abolitionist underground. In 1848, they arrested Quakers John Hunn and Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware. Garrett had long worked with a network of free Blacks who had undertaken the risky business of hiding and transporting runaways. Garrett was fined a crippling sum of $5,000 by Supreme Court chief justice Roger B. Taney. One of his associates Samuel D. Burris was arrested and threatened with enslavement. Burris’s freedom was bought surreptitiously with “abolitionist gold.” He eventually moved to San Francisco and became active in contraband relief efforts during the war, his “interest in the cause of freedom” never faltering.[5] The same year as Garrett’s trial, three seamen Captain Daniel Drayton, Chester English, and Edward Sayres were apprehended in Washington, DC in an abolitionist plot to transport 77 men, women and children to freedom aboard the Pearl, many of whom were property of slaveholding political elite. Tragically, most of the Pearl runaways were sold and Drayton and Sayres imprisoned. In 1850, William Chaplin, the abolitionist who had replaced Torrey in the nation’s capital, was arrested for aiding runaways enslaved by the Georgia congressmen, Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs. Chaplin was in prison for four months before abolitionists raised sufficient money for his bail.

Washington, DC had become an important front in the abolitionist underground. Southern politicians insisted on a new fugitive slave law as part of the sectional Compromise of 1850 as their price for remaining in the Union. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, or the “kidnapping law” as abolitionists called it, criminalized assistance to runaways with fines and imprisonment and required ordinary northern citizens to assist federal marshals in apprehending them. The law caused an outcry among abolitionists, African Americans, many of whom fled to Canada, and led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write her famous antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe based her novel on the many slave narratives published typically under abolitionist auspices. These narratives were the movement literature of abolition offering effective ripostes to proslavery ideology. Truth was stranger than fiction. Henry “Box” Brown shipped himself to freedom in a crate. The lightskinned Ellen Craft and her husband William disguised themselves as master and slave to travel the overground railroad to freedom.

A new generation of fugitive slave abolitionists, of whom Frederick Douglass was only the most famous, came to lead the movement. In the crisis decade of the 1850s, they radicalized abolition advocating direct action against the Fugitive Slave Act. As Jermain Loguen, a fugitive slave himself, said, “It outlaws me, and I outlaw it.”

Jermain Loguen protected freedom seekers in Syracuse, New York (House Divided Project)

A new generation of fugitive slave abolitionists, of whom Frederick Douglass was only the most famous, came to lead the movement. In the crisis decade of the 1850s, they radicalized abolition advocating direct action against the Fugitive Slave Act. As Jermain Loguen, a fugitive slave himself, said, “It outlaws me, and I outlaw it.”[6] While slaveholders and law enforcement summarily kidnapped suspected runaways, abolitionists reactivated their vigilance committees to coordinate resistance. Some of the most spectacular attempted rescues of freedom seekers such as Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns, took place in Boston. Abolitionists formed a militant group, the Anti-Man Hunting League, with nearly 500 members, to confront and remove slave catchers from Massachusetts. The Christiana revolt led by William Parker, the Jerry rescue in Syracuse, the rescue of Joshua Glover in 1854 that led Wisconsin to nullify the fugitive slave law, and the John Price rescue later in Oberlin-Wellington, Ohio were dramatic fugitive slave rebellions. Tubman led one of the last in Troy, New York, the rescue of Charles Nalle in 1860 on the very eve of the Civil War. John Brown, who created an all-Black militia, the League of Gileadites in Springfield, Massachusetts began his career in the Underground Railroad.

The abolitionist underground was a dress rehearsal for the war against slaveholders. Its historical legacy is perhaps larger. In their long fight against the fugitive slave laws, abolitionists came to criticize the criminalization of blackness and a racist law enforcement apparatus. These are injustices we still battle today.

Further Reading

- Abbott, Elena K. Beacons of Liberty: International Free Soil and the Fight for Racial Justice in Antebellum America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. New York: Amistad / HarperCollins, 2005.

- Hodges, Graham Russell Gao. David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Harrold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Olsavsky, Jesse. “Runaway Slaves, Militant Abolitionists, and the Critique of American Prisons, 1830-60.” History Workshop Journal (2021): 1-22.

- Sinha, Manisha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016.

Discussion Questions

- Why were fugitive slave abolitionists such important leaders of the abolitionist movement? Beyond Frederick Douglass, can you name any other fugitive slave abolitionists?

- What was the relationship between vigilance committees and antislavery politics? How could Underground Railroad activity “unite” abolitionists who disagreed over political strategy?

Citations

[1] Garrison uses the term repeatedly: The Liberator September 21, 1838, January 3, 1840, November 3, 1843, April 18, 1845; June 19, October 16, 1846, June 18, 1847, May 14, June 24, 1852, January 2, 1857, March 18, 1859.

[2] L. Maria Child, Issac T. Hopper (Boston, MA: John P. Jewett, 1853),47.

[3] Stephen Middleton, Ohio and the Antislavery Activities of the Attorney Salmon Portland Chase, 1830-1849 (New York: Garland, 1990), 50-73.

[4] Stanley Harrold, The Rise of Aggressive Abolitionism: Addresses to the Slaves (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004).

[5] William Still, The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, PA: Porter & Coates, 1872), 511-4, 531-3.

[6] The Reverend J.W. Loguen, As a Slave and a Freeman (Syracuse, NY: J. G. K. Truair, 1859), ix.

Author Profile

MANISHA SINHA is an Indian-born American historian and the Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut. She received her PhD from Columbia University and is the recipient of numerous fellowships, including from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation. Sinha has authored multiple books including The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (Yale University Press, 2016) which won the Frederick Douglass Book Prize and The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina (University of North Carolina Press, 2000) which was named one of the ten best books on slavery in Politico. She has also written for many well-known sources including the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and the Washington post and served as an advisor and expert for the Emmy nominated PBS documentary, The Abolitionists.

MANISHA SINHA is an Indian-born American historian and the Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut. She received her PhD from Columbia University and is the recipient of numerous fellowships, including from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation. Sinha has authored multiple books including The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (Yale University Press, 2016) which won the Frederick Douglass Book Prize and The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina (University of North Carolina Press, 2000) which was named one of the ten best books on slavery in Politico. She has also written for many well-known sources including the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and the Washington post and served as an advisor and expert for the Emmy nominated PBS documentary, The Abolitionists.

Related Works and Appearances by Manisha Sinha

- A New History of Abolition (OAH, 2017)

- Slavery and Its Legacies (Gilder Lehrman)

- The New Fugitive Slave Laws (New York Review of Books, 2019)

- The Case for a Third Reconstruction (New York Review of Books, 2021)