Banner image: This 1893 painting by Charles T. Webber contributed to the growing popular lore surrounding the Underground Railroad (Cincinnati Art Museum)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

- Listen to the author read a short excerpt from this essay

No aspect of American history has been more saturated with myth than the Underground Railroad. Fantasy has flourished in the absence of adequate information about the underground’s real history. For generations, tales of hidden tunnels, exotic hiding places, cryptic codes, and secret maps abounded. Largely, though not exclusively, these were the invention of white Americans who turned vague local stories into romantic sagas of kindly white philanthropists, usually Quakers, saving hapless Black fugitives who were largely incapable of helping themselves.

William Still (1872), illustration by John Sartain, colorized by Gabe Pinsker (House Divided Project)

Truth was lost not because the underground was completely secret – it wasn’t. Indeed, reports were kept by a number of underground agents, including the Philadelphia activist William Still, whose monumental account of his work, The Underground Railroad, originally published in 1872, details his office’s assistance to hundreds of freedom seekers. Rather, the underground’s real history was willfully forgotten and even actively suppressed during the long years of Jim Crow, when Americans lost interest in the significance of a movement in which Blacks and whites worked together, and which in many areas was organized and led by African Americans. Such intense egalitarian collaboration had no place in the white supremacist narrative that dominated the “redemption” of the southern states from Reconstruction Era Republicans. Eventually, one of the most far-reaching grassroots movements in the nation’s history morphed into little more than a colorful folktale.

Was the Underground Railroad a real railroad? Did the Underground Railroad have a “president”? Were tunnels commonly used to move fugitives from one place to another?

Was the Underground Railroad a real railroad? Some people imagined that there was an actual railroad that carried fugitives north to freedom and that it even ran underground. “Underground Railroad” is a metaphor. Decades before railroads even existed, groups of white and Black antislavery activists were helping freedom seekers elude their pursuers. This embryonic underground initially operated without any general name at all. Some participants simply referred to it as a “line of posts” or “chain of friends.” The term “Underground Railroad” first came into frequent use in the 1840s as iron railroads expanded across the northern states and their speed and efficiency captured the popular imagination. Although the underground was never literally a railway as such, its operatives did utilize whatever innovations might hasten freedom seekers on their way, including steamboats and, yes, railroads. Underground collaborators employed by railways sometimes stashed fugitives on their trains, while Harriet Tubman shepherded at least some of her charges through Grand Central Station in New York City, where she simply bought them tickets to Albany.

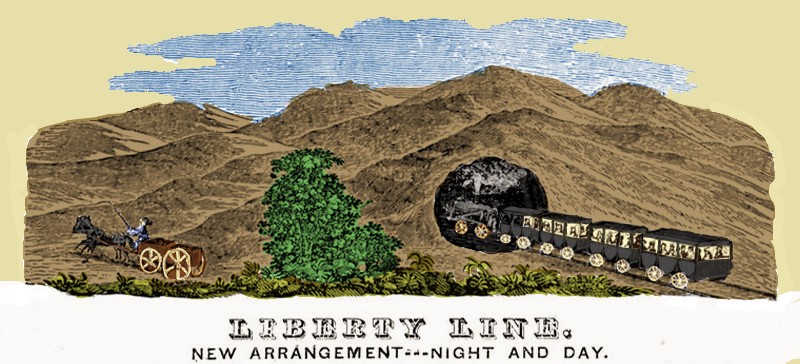

1844 illustration from abolitionist newspaper, colorized by Gabe Pinsker (NYPL Digital Gallery)

Did the Underground Railroad have a “president”? The underground should be thought of as a loose web of linked “stations,” a sprawling network with no center, something like the modern internet. As Isaac Beck, a stationmaster in Ohio put it, “There was no regular organization, no constitution, no officers, no laws or agreement or rule except the ‘Golden Rule,’ and every man did what seemed right in his own eyes.”[1] Quaker activist Levi Coffin was sometimes referred to by admirers as the Underground Railroad’s “general director,” because of his long service, first in his native North Carolina, and later in Indiana and Ohio. But he was never more than one “stationmaster” among equals, although he is estimated to have assisted more than one thousand fugitives during his forty-year career.

“The Underground Railroad” (1893) oil painting by Charles T. Webber with detail showing Levi Coffin helping an enslaved woman (Cincinnati Art Museum)

Were tunnels commonly used to move fugitives from one place to another? Stories about tunnels that were allegedly built by the Underground Railroad are numerous in many northern states, and images of such purported sites can readily be found on the internet. The existence of something resembling a tunnel is not infrequently treated as physical confirmation of Underground Railroad activity, even when documentary sources are lacking. Folk tales and overly zealous amateur historians assert that such tunnels enabled fugitives to secretly move from house to house, from neighborhood to neighborhood, and – notably in the Ohio River Valley, New York’s Hudson River Valley, and on the shores of Lake Ontario – from safe houses to waiting ships. One alleged tunnel beneath the town of Sodus Point, New York, northeast of Rochester, would have been no less than 1,200 feet long, a prodigious feat of labor in a place where there was virtually no chance of a fugitive being recaptured. Despite the legends, there is no evidence that tunnels were ever purpose-built by the underground. Nearly all stories about tunnels date from long after the Civil War, when the Underground Railroad had faded into legend and the fantasy of a railroad that ran underground fed popular rumors of actual tunnels. Nearly all the tunnels said to be associated with the Underground Railroad have been proven to have been created for other purposes years after the Civil War, such as sewers, cisterns, storm drains, drainage tunnels, utility conduits, mineshafts, and the ruins of root cellars, old basements, and the like. Ohio university professor Wilbur H. Siebert, who began collecting first-person testimony from hundreds of Underground Railroad veterans in the late nineteenth century, recorded not a single example of a secret tunnel until well into the twentieth century when the veterans were long dead, and rumors of exotic hiding places captured the public’s fancy.

How secret was the Underground Railroad? Did the Underground Railroad use special codes? What about coded songs? Were “quilt maps” a myth, too?

How secret was the Underground Railroad? The underground operated as cautiously as possible in the border states and the South. But it became more and more open the further one traveled north, until in New England, upstate New York, and the upper Midwest it was barely hidden at all. In Syracuse, New York, stationmaster Rev. Jermain Loguen even advertised his home in local newspapers as the main underground station in the city.[2] Although stories of exotic “hidey-holes” constructed to secrete fugitives are common, few stand up to scrutiny. John Todd, who lived on the shore of the Ohio River in Indiana is reported to have built a double fireplace that could be entered from the top, next to his home’s real chimney, and a Pennsylvania miller who lived a few miles from the Maryland state line is plausibly said to have hidden fugitives in a tiny room behind his grist mill’s water wheel. Based on recent archaeology, it also seems that the noted abolitionist congressman Thaddeus Stevens may have sometimes hidden fugitives on his property in a dry cistern that could only be reached by means of a crawl space several feet long. It is clear from records left by activists that freedom seekers were typically invited to rest in a stationmaster’s kitchen, parlor, or spare room, or to hide, if necessary, in a nearby barn, cornfield, or forest.

LancasterHistory is currently preserving the cistern at the Thaddeus Stevens – Lydia Hamilton Smith historic site in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (Community Heritage Partners)

Did the Underground Railroad use special codes? Cryptic language was uncommon. However, the language of railroading lent itself readily to what activists were already doing: referring to guides as “conductors,” volunteers who offered shelter in their homes as “station masters,” and wagons in which fugitives might be carried as “trains” or “cars.” Joseph Mayo, a Black well-digger in Marysville, Ohio, would receive word that fugitives were waiting to be picked up when someone would come up to him, perhaps in a crowd, and say, “Joe, I have two black steers and a brown heifer at my house,” or “three bucks and two ewes,” and ask that they be driven into town.[3] Other operatives are known to have referred to groups of fugitives as “freight,” “parcels,” or shipments of “finest coal,” “indigo,” or “black ink.” But they mostly used plain English to communicate with each other. However, when secrecy was imperative, some underground cells did invent their own private language. One group of immigrant farmers based in southern Indiana but originally from Yorkshire, in the north of England, simply spoke to each other in their thick native dialect when they talked about underground business.

What about coded songs? It is popularly believed that coded or “map” songs transmitted directions for the north-bound routes that freedom-seekers should follow.[4] For example, “Wade in the Water” is supposed by some to have secretly advised fugitives to go into a swamp or stream where bloodhounds couldn’t follow their scent, while “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” is alleged to have alerted prospective freedom-seekers that an underground guide was near, and “Steal Away” signaled that the singer was planning to escape. As emotive and powerful as such songs were, and remain, there is no evidence that they, or any other songs, were actually used this way. The “directions” provided by supposed “map” songs are so vague or obvious – such as “wade in the water” – as to be virtually useless to actual fugitives, whose friends could communicate much more precise information simply by talking to them. The song most closely associated with the Underground Railroad, “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” was at least partly fabricated by an early twentieth century folklorist, and then revised and popularized by the folk-singing group known as “The Weavers,” according to musicologist Joel Bresler. For instance, its most memorable line — “The old man is awaitin’ for to carry you to freedom” — couldn’t have been sung by fugitive slaves because it was written by the white singer Lee Hays in the 1940s.[5] Although the song may not be an artifact of the Underground Railroad, it is an evocative modern-day celebration of the spirit of the underground.

Listen to the first commercially released recording of “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” performed in 1951 by The Weavers (courtesy of musicologist Joel Bresler)

Were “quilt maps” a myth, too? Yes. The false idea that certain antebellum quilts contained secret “maps” to guide freedom-seekers on their flight became popular only in the late 1990s, initially among quilters in Charleston, South Carolina. Numerous websites, teacher’s guides, and books now purport to “decrypt” a panoply of patterns, knots, stitching, and colors which they claim collectively amounted to a cartographical lexicon: the “monkey wrench” supposedly advised prospective fugitives to prepare their tools for the journey; the “wagon wheel” told them to board a wagon; the “bear’s paw” indicated a mountain trail; and others a cabin to shelter in, a zig-zag path to be followed, a crossroads, and so on. Quilting historians have shown that quilts produced by enslaved people were quite simple, and that many if not all the patterns alleged to compose the “maps” actually date from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition, the “maps” incorporate patterns so complicated that they would have been of little practical use to fugitives attempting to make their way across hundreds of miles of hostile and unfamiliar territory. Overland escapes from slavery in South Carolina, for instance, were almost unheard of. One historian, Laurel Horton, determined that a quilter would have to make eleven different patchwork quilts to encompass all the patterns necessary for an imagined route from South Carolina to the North.[6]

Promoters of the “map quilt” myth assert that such maps were created because slaves could neither read nor write and therefore had to be taught to memorize routes many hundreds of miles long by means of symbols. However, such fictions perversely ignore the way in which enslaved people actually communicated with each other: with plain language. They also assume that many if not most freedom-seekers were traveling vast distances from the Deep South to the free North and Canada. In reality, extremely few enslaved people escaped from the Deep South, and those who did mostly managed to hide aboard ships leaving southern ports. A few, usually from Texas, also traveled westward in hope of reaching slavery-free Mexico. Most successful escapes were comparatively short and were undertaken by fairly well-informed men and women. The vast majority came from the states that bordered free states, mainly Maryland, Virginia, and Kentucky, with smaller numbers fleeing from other states in the upper South. Not surprisingly, the greatest numbers came from the upper parts of the northernmost slave states, usually just a few days or even hours’ walk from the free states, where detailed information was readily available about northbound routes, river crossings, and sources of aid.

The legends of the Underground Railroad may charm and thrill, but they are not history.

The legends of the Underground Railroad may charm and thrill, but they are not history. Certainly, there is a place for oral tradition and folklore in grappling with the tangled story of the Underground Railroad, which was never uniform or static across the states. Almost any legend may contain a grain of fact that can help us understand the diversity of the underground, and how it worked from place to place. But legends alone do not help us understand the realities of slavery, abolitionism, the struggle of enslaved people for freedom, the real experiences of fugitives, or the way the Underground Railroad actually operated. The Underground Railroad was only incidentally comprised of “lines,” “safe-houses” or “stations,” cryptic lingo and real or imagined hiding places. It was, most important, a network of people: men and women, Black and white, fugitives and their helpers, united in a common endeavor to save human beings from degradation and to subvert the institution of slavery, demonstrating that bi-racial cooperation was not only possible, but also imperative to overcome the divisions wrought by racism.

Further Reading

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. New York: Amistad/Harper Collins, 2005.

- Coffin, Levi. Reminiscences. Cincinnati: Western Tract Society, 1879.

- Gara, Larry. The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996.

- Larson, Kate Clifford. Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero. New York: Random House, 2003.

- Siebert, Wilbur H. The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom. New York: Macmillan, 1898.

- Still, William. The Underground Railroad. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872.

Discussion Questions

- How does Charles Webber’s famous 1893 painting help perpetuate some of the popular “myths” of the Underground Railroad?

- Why have myths about the Underground Railroad been so persistent and widespread in American history?

- Why are historians so skeptical about various folklore claims regarding coded Underground Railroad songs or quilts?

- As Bordewich acknowledges, there is “a place for oral tradition and folklore” in the study of the Underground Railroad. But how should teachers and site interpreters balance the need to respect those traditions with a determination not to perpetuate popular legends?

Citations

[1] Isaac Beck interview with Wilbur H. Siebert, December 26, 1892, Wilbur H. Siebert Collection, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio.

[2] Syracuse Daily Standard, November 25, 1854.

[3] Marysville (OH) Tribune, April 27, 1881.

[4] “Music Was The Secret Language Of The Underground Railroad.” https://medium.com/dose/music-was-the-secret-language-of-the-underground-railroad

[5] Follow the Drinking Gourd: A Cultural History, curated by musicologist Joel Bresler, www.followthedrinkinggourd.org

[6] “The Underground Railroad Quilt Controversy: Looking for the ‘Truth.’” Paper presented by folklorist and quilting historian Laurel Horton at the International Quilt Center and Museum, University of Nebraska, March 22, 2006. https://www.quilting-in-america.com/Underground-Railroad-Quilts.html

Author Profile

FERGUS M. BORDEWICH is an American historian who holds degrees from the City College of New York and Columbia University. His books include Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (HarperCollins, 2005) which was selected as one of the American Booksellers Association’s “ten best nonfiction books” in 2005, and more recently Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought The Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, And Remade America, (Knopf, 2020). His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, American Heritage, The Atlantic, Harper’s, New York Magazine, GEO, and Reader’s Digest, among others.

FERGUS M. BORDEWICH is an American historian who holds degrees from the City College of New York and Columbia University. His books include Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (HarperCollins, 2005) which was selected as one of the American Booksellers Association’s “ten best nonfiction books” in 2005, and more recently Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought The Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, And Remade America, (Knopf, 2020). His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, American Heritage, The Atlantic, Harper’s, New York Magazine, GEO, and Reader’s Digest, among others.

Related Works and Appearances by Fergus M. Bordewich

- Congress at War (Library of Congress, 2020)

- Radical Remembering: Exploding Myths and Recovering the Realities of Abolition and the Underground Railroad (New Bedford Historical Society, 2022)