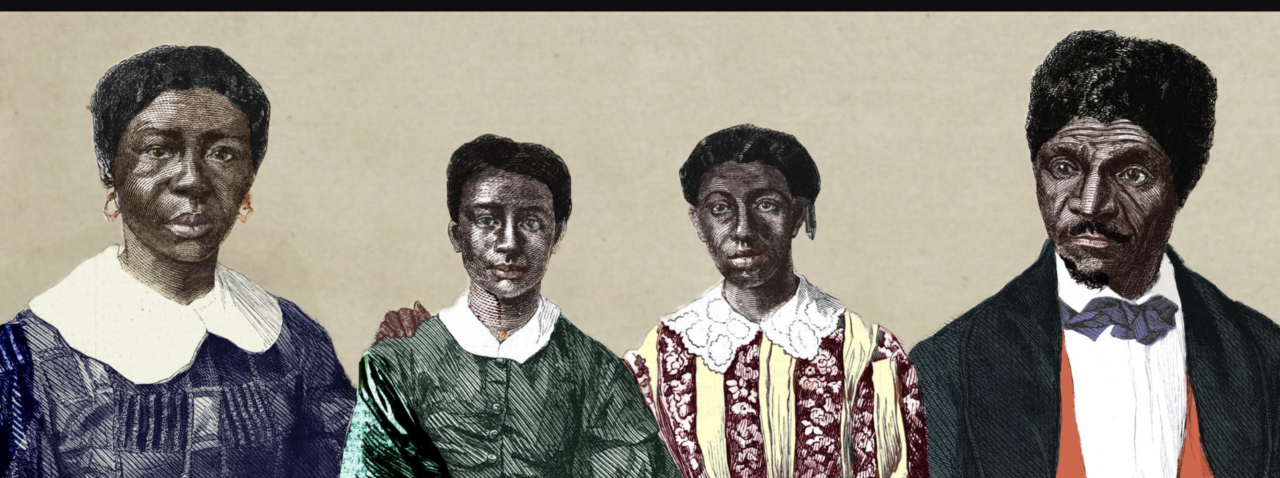

Banner image: Harriet and Dred Scott were the rare freedom seekers who sought liberation for their family by lawsuit rather than by flight. Their legal struggle ultimately helped change the US Constitution after the Civil War. (Composite image created from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, May 1857, colorized by Cooper Wingert, House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

Persons held as slaves in America sought to escape their bondage from the seventeenth century until the end of slavery in 1865. During the American Revolution, thousands of slaves escaped as the chaos of war and the need for soldiers and civilian labor beckoned freedom seekers toward both the British armies and the Patriot armies. Slaveowners always tried to recover those who escaped but colonial and early state governments never provided any systematic way to help owners. Meanwhile, the dismantling of slavery in the newly independent northern states combined with the emergence of antislavery organizations and a rise in opposition to slavery in the North and some parts of the South, worked to the benefit of those seeking to escape.

Near the end of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, South Carolina’s Pierce Butler introduced the Fugitive Slave Clause, which in its final form, prohibited states from emancipating slaves who had escaped from other states, and required that fugitive slaves be “delivered up” on the claim of their owners. At the Virginia ratification convention, James Madison pointed to this provision as a reason for Virginia to accept the new Constitution. He reminded his fellow delegates: “Another clause secures us that property which we now possess. At present, if any slave elopes to any of those states where slaves are free, he becomes emancipated by their laws; for the laws of the states are uncharitable to one another in this respect.” He then quoted from the Constitution, arguing “this clause was expressly inserted, to enable owners of slaves to reclaim them.” He emphatically asserted, “This is a better security than any that now exists” and shows that slavery was protected by the new Constitution.[1]

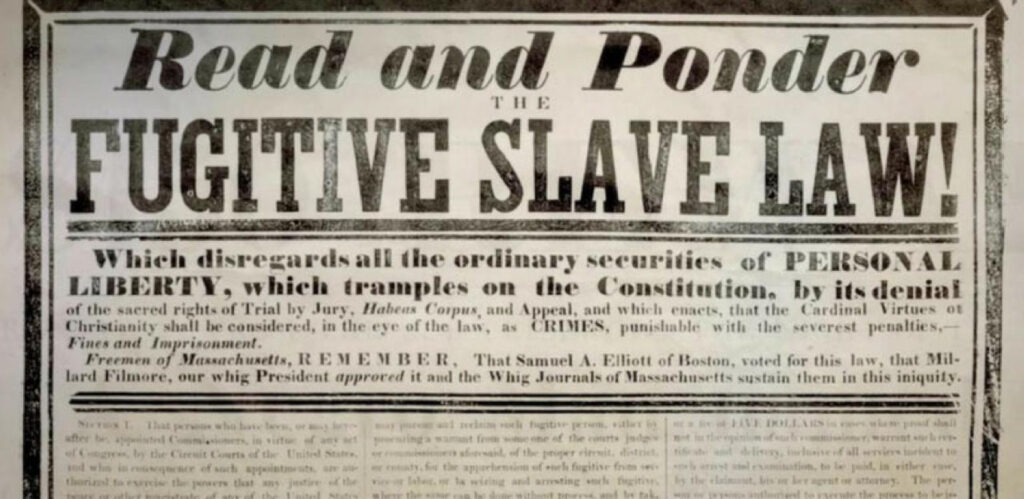

This constitutional clause led to federal laws in 1793 and 1850, which provided mechanisms to help slaveowners recover fugitive slaves. The constitutional provisions and these laws made the Underground Railroad necessary because the federal laws made it illegal to openly help slaves seeking freedom. Whenever we think about the Underground Railroad, we must begin with the understanding that those who helped slaves escape were violating federal laws and could be fined, sued for enormous amounts of money, and sent to jail. They were also resisting the US Constitution and the national government. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 promised that persons owning slaves would be able to recover their human property when these slaves escaped to other states, and that the states could not make fugitive slaves legally free. In 1787, when the Constitution was written, two states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, had abolished slavery, and Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island were in the process of doing so. Without the Fugitive Slave Clause, these and future free states could have protected the liberty of any enslaved people who reached their borders. But because of the constitutional clause and the two federal laws passed to implement it, enslaved people who escaped to the North had to hide their whereabouts and identity, since they were legally fugitives who could be claimed by their southern owners. People who helped fugitives also had to operate “underground” since they were violating the law.

The US Constitution’s fugitive slave clause and a pair of federal laws attempted to suppress the fugitive slave crisis, but never fully succeeded in deterring freedom seekers (House Divided Project)

The Fugitive Slave Clause was vague and gave no guidance as to how it was to be enforced. However, in 1793 Congress passed a law to implement it, and in 1850 a new law (technically an amendment to the 1793 law) dramatically enhanced federal jurisdiction and law enforcement. Early in the Civil War the national government began to move away from federal enforcement, and in 1864 repealed both of the fugitive slave laws. The ratification of the 13th Amendment, ending all slavery in the United States, made fugitive laws meaningless. However, some legal doctrines, developed by the Supreme Court to enforce the federal fugitive slave code, remain part of our constitutional law to this day.

The Constitutional Clause

The Constitution provided that:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.[2]

Article IV, where this clause is found, dealt mostly with interstate obligations, such as the requirement that one state give “Full Faith and Credit” to the laws and court decisions of another state. Sections 1, 3, and 4 of this Article provided for congressional action to implement them. But none of the three clauses in Section 2 (dealing with the Privileges and Immunities of citizens of one state visiting another, fugitive criminals, and fugitive slaves) contained any mention of a role for Congress. Because of its language and its placement in the structure of the Constitution, a strong argument could be made that the Clause did not anticipate federal laws to enforce it, or even that the federal government lacked the constitutional power to enforce it.

New York chancellor Reuben Walworth declared the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional in the landmark ruling Jack. v. Martin (Historical Society of the New York Courts)

New York’s highest court took this position in Jack v. Martin (1835), with Chancellor Reuben H. Walworth asserting that the 1793 law was unconstitutional. He explained that he had “looked in vain among the powers delegated to congress by the constitution, for any general authority to that body to legislate on this subject. It is certainly not contained in any express grant of power, and it does not appear to be embraced in the general grant of incidental powers contained in the last clause of the constitution relative to the powers of congress.” Chief Justice Joseph Hornblower of New Jersey took the same position.[3]

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1793

Despite the lack of specific enforcement power, Congress passed a law in 1793 regulating both “fugitives from justice” and “fugitives from labor” or fugitive slaves. Significantly, reflecting the power of slavery in American politics, Congress never attempted to enforce the Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, because that would have required that the slave states honor the rights of free Black citizens from the North.

The 1793 law set up a barebones process for bringing fugitive slaves back to those who claimed them. Under the law, slaveowners could seize their slaves and bring them to a local, state, or federal judge, who would issue certificates of removal to slave catchers, “upon proof to the satisfaction of such Judge or magistrate, either by oral testimony or affidavit” that the person before the judge was actually legally owned as a slave by the claimant. The law contained no precise standards for proof. Anyone who might “knowingly and willingly obstruct or hinder” the return of a fugitive slave was subject to a $500 penalty (an enormous sum of money at the time) as well a civil suit for the value of any slaves lost and any costs associated with recovering them. Lawsuits under these provisions financially devastated the Ohio abolitionist John Van Zandt and cost a number of opponents of slavery in places such as South Bend, Indiana significant amounts of money.

Initially, however, there were very few cases involving the 1793 law, and almost no controversies under it. Yet by the 1820s, a number of northern states passed personal liberty laws in response to kidnappings of free Black children in Philadelphia and other port cities. These laws were not designed to prevent the return of actual fugitive slaves (despite what many southern political leaders would later claim) but were passed to protect the North’s free Black population. By this time all the northern states had either abolished slavery outright, banned it in their new state constitutions, or passed gradual abolition acts, which prevented any new slaves from being born in the states or imported into the states. The personal liberty laws required that slave catchers actually prove that someone “owned” a person seized as a slave, allowing northern state and local judges to evaluate the evidence of this ownership, and then authorizing those judges to refuse the removal of Blacks whom they believed were actually free.

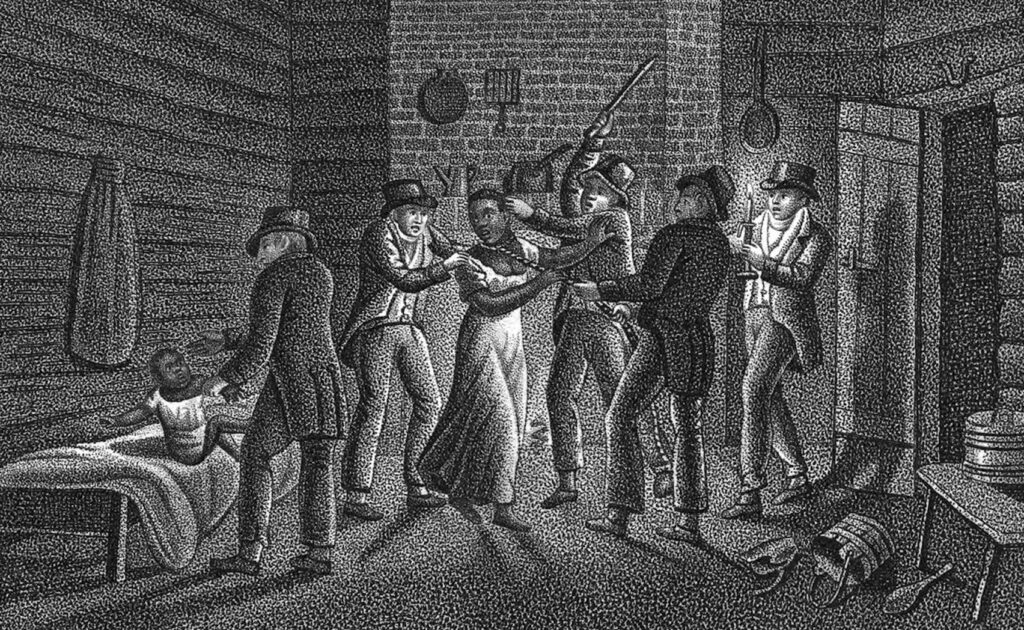

Abolitionist illustration criticizing the activities of slave catchers under the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act (Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States, 1817 )

In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) the US Supreme Court ruled 8-1 that states could not interfere with the return of fugitive slaves, that state personal liberty laws were unconstitutional if they hindered the return of such fugitives, that the 1793 federal law was fully constitutional, and that slave catchers had a constitutional right to seize and remove fugitive slaves without any legal hearing, under the common law principle of recaption. This part of the ruling became known as a right of “self-help,” but because there would be no hearing or law enforcement officer involved, this part of the decision essentially set the stage for even more widespread kidnapping of free Blacks in the North.[4]

The 1842 case involved four Maryland men, including Edward Prigg, a local farmer who joined his neighbor in going to Pennsylvania to seize Margaret Morgan, a woman whom his neighbor claimed as a slave. Prigg and the other three Marylanders had taken Margaret Morgan and her children from Pennsylvania to Maryland, after a Pennsylvania state judge had released them. At least one of the children had been born in Pennsylvania, and so was free at birth under Pennsylvania law, while Morgan, who had never been claimed as a slave by anyone, had lived her entire life as a free person and was listed in the 1830 census as a free person of color living in Maryland. In overturning Prigg’s conviction for kidnapping, Supreme Court justice Joseph Story argued that state officials should enforce the 1793 law and had full jurisdiction to do so (and definitely could not obstruct it), but that Congress could also not constitutionally compel state officials to enforce a federal law. Morgan and her children were then sold into slavery and disappeared from the records.

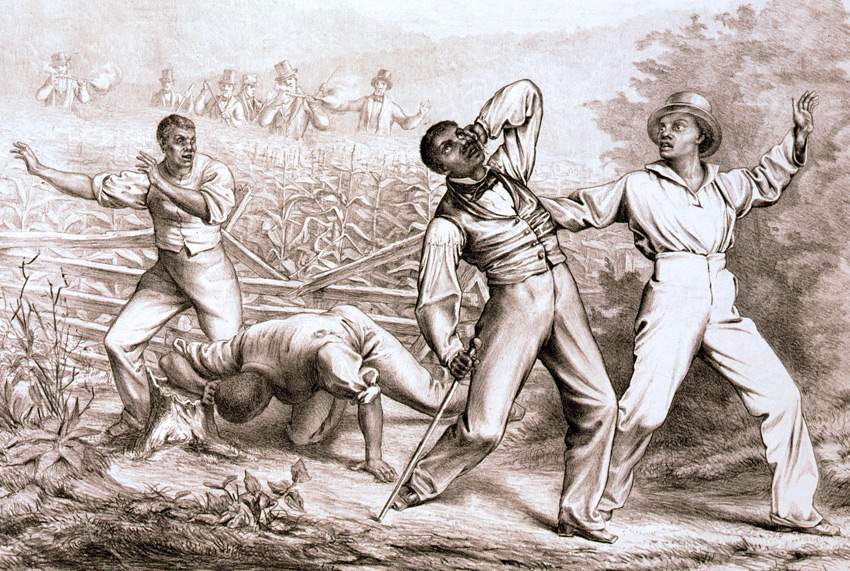

No longer able to protect the liberty of their free Black citizens (such as Morgan’s free-born child), many northern states passed new personal liberty laws prohibiting state officials from taking any part in the return of fugitive slaves. In addition, after Prigg many state judges simply refused to hear fugitive slave cases, sometimes asserting incorrectly that under Prigg they had no jurisdiction.[5] In most states, there was only one federal judge and one federal marshal, so, without the assistance of state authorities it was difficult for owners of slaves or their agents to obtain support for returning fugitives. Slaveowners or their agents could capture runaways on their own, but this was expensive and difficult. Slave catchers in “hot pursuit” of fugitives might successfully capture them, but once fugitive slaves blended into free Black communities or moved north of the Ohio River or the Mason-Dixon line, finding and capturing them was difficult. The Underground Railroad effectively allowed many fugitives to move further away from slavery in the North, or even go to Canada. One example of “hot pursuit” occurred in Ohio in 1842. Some fugitives had been walking on a road near Cincinnati when an abolitionist, John Van Zandt, offered them a ride in his wagon. Slave catchers with no authorization from Jones then stopped Van Zandt’s wagon and seized eight of the runaways, but one slave eluded capture. In Jones v. Van Zandt (1847) the US Supreme Court upheld the owner’s suit under the 1793 law for the value of the missing slave plus the owner’s costs in recovering the others. The Court rejected Van Zandt’s argument claiming he had no knowledge that the people who rode in his wagon were fugitive slaves, and thus should not be held liable for their escape or the cost of recovering them.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

But with most northern states refusing to authorize the use of their jails or allow state officials to help recapture fugitive slaves, southern slaveowners began demanding stronger federal protection. They were successful with the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. This act provided for the potential appointment of US commissioners in every county of the North to help enforce the law. While US commissioners had existed since the 1790s, they were mostly appointed in large cities where there was a federal court, or in port cities where there were customs officials. Under the 1850 law, any federal commissioner could call on local law enforcement (if they were able to help), ask for the US military to enforce the law or have the state militias called up, and deputize willing citizens. This was the first time in US history that there was such a federal law enforcement system coordinated at the local level. However, very few new commissioners actually got appointed, in part because the position did not come with regular salary and so commissioners were only compensated each time they filled out any sort of form, and in part because in much of the North no one was willing to accept a new commission owing to the fierce public opposition to the new Fugitive Slave Law. In some northern cities, commissioners even resigned from their positions, while others simply refused to hear fugitive slave cases.[6] The law provided for $1,000 dollar fines and up to six months in jail for anyone interfering with its enforcement and also allowed slaveholders to receive up to $1,000 for every slave not recovered because of private interference. Commissioners were paid by owners for hearing cases. The commissioners received $10 if they found in favor of the master, but only $5 if they freed the alleged slaves. According to proponents of the law, the difference in the fees was based on the fact that to return a slave, the commissioner had to fill out more paperwork. However, most opponents saw this as an attempt to corrupt the process by effectively bribing the commissioners to side with slave catchers. It is worth noting that at this time $10 was the equivalent of one to two week’s wages for many workers.

Antislavery broadside attacking the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act (Library of Congress)

The 1850 law worked reasonably well when slave catchers actually found an escaped slave and brought the person before a federal judge or commissioner, or when slaveowners were able to seize their slaves and drag them back to bondage, under the right of “self-help” that Justice Story articulated in Prigg v. Pennsylvania. But white southerners found and captured relatively few Blacks. Determining how many fugitives were returned is not a simple matter. In The Slave Catchers (1970), historian Stanley Campbell counted just over 300 Blacks taken south. New research by Cooper H. Wingert, however, details how relatively few of those Blacks were taken south under formal rendition procedures.[7] No scholar has focused on the period after 1860, although some fugitive slaves were returned during the Civil War. However, whatever the exact numbers, the bottom line is that far more freedom seekers achieved self-liberation during this era than were returned as fugitive slaves under either the 1793 or 1850 laws, or under the slaveholder’s right of recaption.

The 1850 law worked reasonably well, when slave catchers actually found an escaped slave and brought the person before a federal judge or commissioner

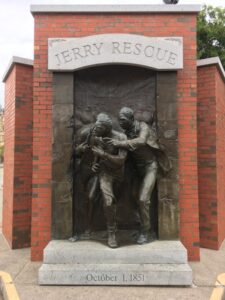

Jerry Rescue, Syracuse, NY (1990) (Slavery Monuments)

Yet, the overwhelming majority of African Americans seized as fugitives were returned to bondage. But even then, spectacular and sometimes lethal incidents of resistance to the law captured headlines. There were dramatic rescues of enslaved people in Boston (1851), Syracuse, New York (1851), Milwaukee, Wisconsin (1854), and Oberlin-Wellington, Ohio (1858). In Christiana, Pennsylvania in September 1851, there was a fatal fire-fight between Black resisters led by fugitive slave William Parker and a slave catching posse that resulted in the death of a Maryland slaveowner. Before the shooting began, a US marshal snuck away from the scene to avoid the gunfight. Parker later took a train to Rochester, New York, where he stayed with Frederick Douglass, who put him on a boat for Canada. Parker gave the pistol allegedly used to kill the slave owner to Douglass. Eventually nearly forty people were indicted for treason, but the cases ended when US Supreme Court Justice Robert Grier, who presided over the trial, essentially directed the jury that resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law, while a crime, was not treason. A week after the Christiana “riot” (as it was called), opponents of the law in Syracuse, New York rescued a fugitive named Jerry Henry from the custody of the US marshal, and later took him to Canada. Indictments for that event led mostly to acquittals and hung juries. One African American man, Enoch Reed, was convicted in federal court but passed away of natural causes while his case was on appeal. A few rescuers were convicted and briefly jailed in Wisconsin and Ohio, but most trials for resisting the 1850 law ended up in hung juries or acquittals. In 1854 a week-long trial in Boston over the status of Anthony Burns led to demonstrations and a failed rescue which resulted in the death a federal deputy, William Batchelder, who had been recruited just for the Burns trial. The courthouse in Boston was ringed with heavy anchor chain and surrounded by militia and federal troops with cannon facing the crowds. Burns was sent back to Virginia on a federal revenue cutter and sold for about $900 (though he was eventually freed by sale the next year). It is estimated the federal government spent close to $100,000 to remove him from Boston.

In explaining why they were seceding in 1860 and 1861, South Carolina, Texas, and other Deep South states pointed to the longstanding northern resistance over enforcement of the fugitive slave laws. But, as historian Stanley Harrold noted in his book Border War, most fugitives escaped from Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland, and those states remained in the union in part because they realized that if they left the United States, there would be no way to recover slaves escaping northward to a different country.[8] At the same time, however, it is estimated that as many as 20,000 slaves escaped to the North between 1840 and 1860 and more than 90 percent of them were never returned. Similarly, while some abolitionists such as John Van Zandt paid a huge price for helping slaves escape when they were successfully sued, most people who violated the 1793 and 1850 laws were neither sued nor jailed.

The controversial system finally ended during the Civil War. In the revised Articles of War passed in March 1862, Congress prohibited the use of the US army to return fugitive slaves. By this time, fugitives from the South were being welcomed by US troops and hired by the US army, first as civilian workers and then after July 1862 eligible Black men were also enlisting as soldiers. In 1864, Congress finally repealed both the 1793 and the 1850 fugitive slave laws.

Further Reading

- Campbell, Stanley W. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

- Finkelman, Paul. Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson (3rd). New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Finkelman, Paul. Slavery in the Courtroom. Washington, DC, Government Printing Office, 1985.

- Finkelman, Paul. Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Harrold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Lubet, Steven. Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Morris, Thomas D. Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780-1861. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

[1] Jonathan Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, 5 vols. (New York: Burt Franklin, 1987, reprint of 1888 edition) 3:453.

[2] US Constitution, Art. IV, Sec. 2, Cl. 3.

[3] Jack v. Martin, 11 Wendell (N.Y.) 311 (1834); Paul Finkelman, “Chief Justice Hornblower of New Jersey and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, in Paul Finkelman, ed., Slavery & the Law (Madison, WI: Madison House, 1997), 113-142.

[4] For a full discussion of Story’s opinion, see Paul Finkelman, “Story Telling on the Supreme Court: Prigg v. Pennsylvania and Justice Joseph Story’s Judicial Nationalism,” Supreme Court Review, 1994: 247.

[5] Paul Finkelman, “Prigg v. Pennsylvania and Northern State Courts: Anti-Slavery Use of a Pro-Slavery Decision,” Civil War History 25 (1979): 5-35.

[6] Cooper H. Wingert, “Fugitive Slave Renditions and the Proslavery Crisis of Confidence in Federalism, 1850–1860,” Journal of American History 110 (June 2023).

[7] Wingert, Fugitive Slave Renditions; Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970. .

[8] Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 194-205.

Further Reading

- Campbell, Stanley W. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

- Finkelman, Paul. Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson (3rd). New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Finkelman, Paul. Slavery in the Courtroom. Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1985.

- Finkelman, Paul. Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Harrold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Lubet, Steven. Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Morris, Thomas D. Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780-1861. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

Discussion Questions

- What does Paul Finkelman mean when he writes that constitutional provisions and federal laws “made the Underground Railroad necessary”?

- According to Finkelman, slaveholders frequently demanded greater federal protections for slavery and slave-catching, while northern states responded by asserting legal rights to protect their free Black residents from kidnapping. How does this dynamic challenge traditional understandings about states’ rights and the coming of the Civil War?

Citations

[1] US Constitution, Art. IV, Sec. 2, Cl. 3.

[2] Paul Finkelman, “Chief Justice Hornblower of New Jersey and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, in Paul Finkelman, ed., Slavery & the Law (Madison, WI: Madison House, 1997), 113-142.

[3] Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 194-205.

Author Profile

PAUL FINKELMAN is a noted American legal historian who has held several distinguished faculty positions. In 2024 he will hold the Boden Chair at Marquette University College of Law. He received his undergraduate degree in American studies from Syracuse University and his master’s degree and doctorate in American History from the University of Chicago. He was ranked among the most cited legal historians according to “Brian Leieter’s Law School Rankings.” Finkelman is the author of more than 200 scholarly articles and the author or editor of more than fifty books including An Imperfect Union (The University of North Carolina Press, 1981) and recently Supreme Injustice (Harvard University Press, 2018). His op-eds and shorter pieces have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, USA Today, and on the Huffington Post.

PAUL FINKELMAN is a noted American legal historian who has held several distinguished faculty positions. In 2024 he will hold the Boden Chair at Marquette University College of Law. He received his undergraduate degree in American studies from Syracuse University and his master’s degree and doctorate in American History from the University of Chicago. He was ranked among the most cited legal historians according to “Brian Leieter’s Law School Rankings.” Finkelman is the author of more than 200 scholarly articles and the author or editor of more than fifty books including An Imperfect Union (The University of North Carolina Press, 1981) and recently Supreme Injustice (Harvard University Press, 2018). His op-eds and shorter pieces have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, USA Today, and on the Huffington Post.

Related Works and Appearances by Paul Finkelman

- The Revolutionary Summer of 1862 (Prologue, 2017)

- Reconstruction and the US Supreme Court (CSPAN, 2019)

- America’s ‘Great Chief Justice’ Was an Unrepentant Slaveholder (Atlantic, 2021)

- Supreme Injustice (Monticello, 2021)