Vigilance leaders and freedom seekers resist the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act at Christiana, killing a Maryland slaveholder and evading punishment from federal authorities

Date(s): escaped 1849, resistance September 11, 1851

Location(s): Christiana, Pennsylvania

Outcome: Freedom, slaveholder Edward Gorsuch killed

Summary:

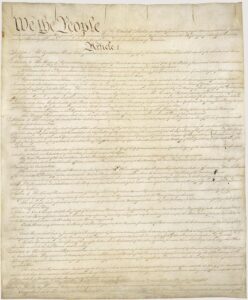

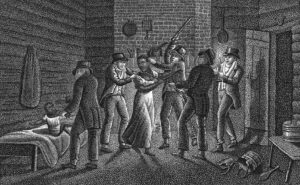

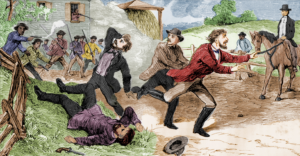

In 1849, four enslaved men, Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond, escaped from Maryland slaveholder Edward Gorsuch and settled near Christiana in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Two years later in September 1851, Gorsuch discovered the whereabouts of his runaways with the help of a local spy and made arrangements in Philadelphia with the fugitive slave commissioner to organize a posse that would try to apprehend the four freedom seekers under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. But operatives from the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee learned of these plans and quickly notified a vigilance group in Christiana, led by Black couple William and Eliza Parker.

Gorsuch’s posse arrived at the Parker stone farmhouse (where at least some of the runaways were hiding) just after dawn on September 11, 1851, but William Parker stubbornly refused them entrance. Eliza Parker then blew a horn to help alert their neighbors and local vigilance supporters to the unfolding confrontation. Violence erupted. Black activists shot Gorsuch dead and wounded his son. The federal officers fled the scene. Pro-slavery forces from across the country immediately denounced the resistance but government officials moved too slowly and the Parkers and the four young freedom seekers escaped to Canada. Federal prosecutors eventually charged 38 local men with treason, to send a stern political message, but the trial, held in Philadelphia in late November and early December, proved to be a political catastrophe for the Fillmore Administration. The jury acquitted the first defendant, a white farmer named Castner Hanway, in about fifteen minutes. Prosecutors then released the rest of the accused. There were other violent fugitive slave rescues in 1851, most notably in Boston, Massachusetts and Syracuse, New York, but the Christiana resistance was the most dramatic and decisive victory for the abolitionist forces in their escalating campaign to undermine the federal Fugitive Slave Law.

Related Sources

- New Orleans (LA) Picayune, “The Fugitive Slave Riot,” September 14, 1851

- Columbus (OH) Ohio Statesmen, “Great Riot,” September 16, 1851

- (Columbus) Ohio State Journal, “The Christiana Tragedy,” September 23, 1851

- Rochester (NY) Frederick Douglass’ Paper, “Freedom’s Battle at Christiana,” September 25, 1851

- Louisville (KY) Journal, “The Christiana Outrage,” September 29, 1851

- Memphis (TN) Appeal, “Treason!,” October 10, 1851

- John Henry Hill to William Still, January 19, 1854

Related Sites

The Parker “riot” house in Christiana, as it was originally known, is no longer standing, but there are some existing structures and historic sites within the NPS Network to Freedom which can help commemorate this episode, including the Gorsuch Tavern in Verona, Maryland, Eliza Parker’s escape site at Belle Vue Farm in Havre de Grace, Maryland, and Zercher’s Hotel in the town of Christiana, Pennsylvania, where government authorities first conducted the inquest in the aftermath of the violence on September 11, 1851. To view more details about these sites and their level of accessibility to the public, consult our various Network to Freedom maps in this online handbook.

Related Essays