Ona Judge defies President George Washington and the new federal fugitive slave law to seize freedom

Date(s): escaped May 21, 1796

Location(s): Mount Vernon, Virginia; Philadelphia; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Greenland, New Hampshire

Outcome: Freedom

Summary:

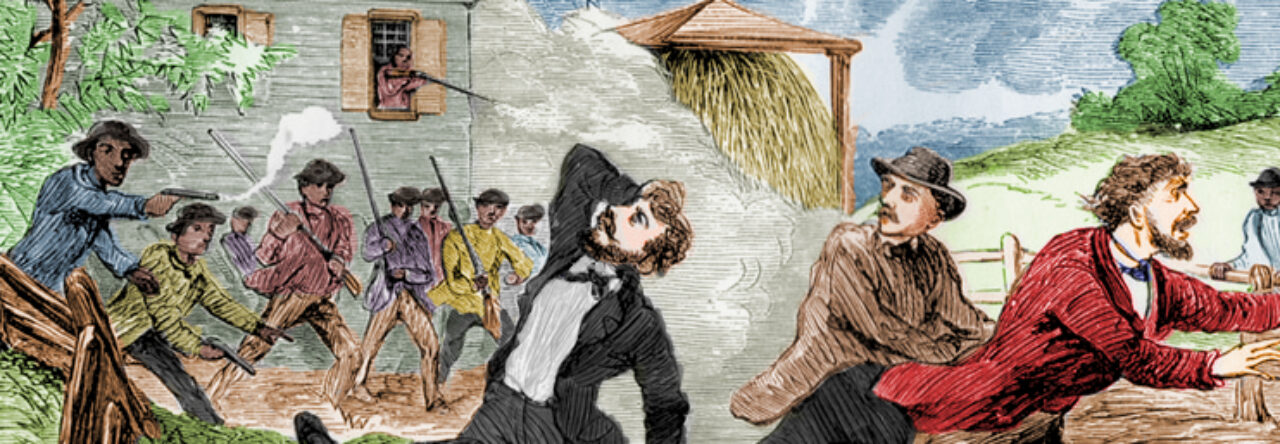

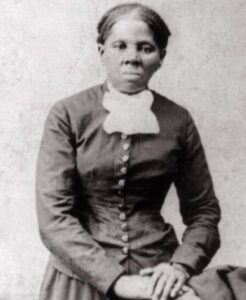

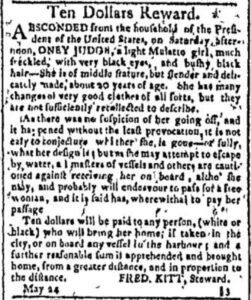

The Washingtons advertised for Judge’s recapture in Philadelphia papers (Encyclopedia Virginia)

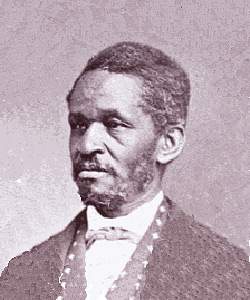

Ona Judge, or “Oney” as the Washington family called her, was born into enslavement in Virginia and became Martha Washington’s personal maid at the age of 10. When George Washington became president, he brought Judge and seven other enslaved people with him to New York, and then to Philadelphia once the nation’s capital moved there. But Pennsylvania’s 1780 Gradual Abolition Act forbade slaveholders from residing in the state with enslaved people longer than six months. To work around the state law, the Washingtons quietly cycled Judge and other enslaved people back between Philadelphia and Mount Vernon. While in Philadelphia, Judge continued her duties for Martha Washington, though her presence in Philadelphia was much more conspicuous than ever before. Judge was given expensive clothing and encouraged occasionally to attend events such as plays and the circus. Judge also seized the opportunity to make connections with Quaker abolitionists and free African Americans in the city. When Judge learned that the Washingtons planned to send her back to Virginia as a wedding gift, Judge decided to take her chances and escape on May 21, 1796, traveling aboard the ship Nancy to New Hampshire. Judge apparently received assistance from the ship’s captain, John Bolles, never disclosing his name until after his death to ensure he would not face punishment.

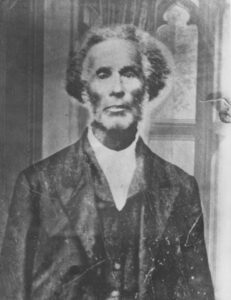

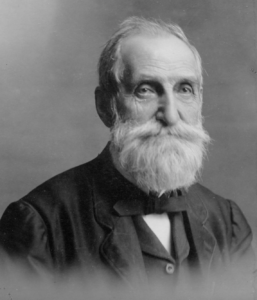

Only months after Judge’s arrival in New Hampshire, however, Martha’s youngest granddaughter Nelly Parke Custis spotted the freedom seeker, and soon after, Washington sent the Portsmouth customs collector, Joseph Whipple, to convince her to return to Philadelphia. Judge agreed on the condition that she would be freed after the Washingtons’ deaths and would not be passed on to serve anybody else. Washington blatantly denied this request and continued his efforts to return Judge through Whipple via the federal 1793 Fugitive Slave Act. However, Washington informed Whipple that he had to tread lightly for fear of antagonizing antislavery Northerners. In any case, Whipple was unsuccessful and in 1793, Judge married Jack Staines, a free black sailor, with whom she had three children. In 1799, Washington requested the help of Burwell Bassett, jr., Martha Washington’s nephew, in returning Judge using the same inconspicuous method that he had once advised Whipple to use. When Bassett first found her in Portsmouth and was unable to convince her to return, he informed New Hampshire senator John Langdon that he planned to seize Judge by force. Langdon secretly warned Judge, who was able to evade Bassett and escape to nearby Greenland. After Washington died in 1799, Judge never was bothered by the family again, though she and her children remained legally vulnerable to capture by the Custis’. Judge went on to outlive her husband and two of her daughters. She was known to still be living in Greenland in the 1840s, when remarkably she was interviewed by the abolitionist Reverend Benjamin Chase.

Related Sources

- George Washington to Oliver Wolcott, jr., September 1, 1796

- Boston Liberator, “Washington’s Runaway Slave,” August 22, 1845

- Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017)