Citation

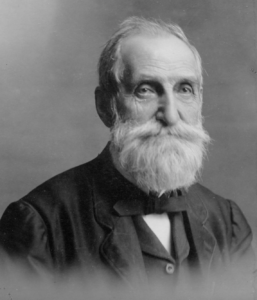

Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery: The Refugee, Or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada (Boston: Jewett, 1856), FULL TEXT via Documenting the American South

Excerpt

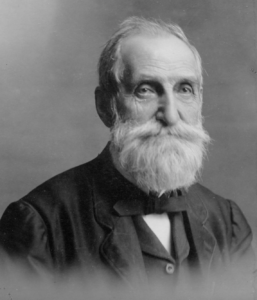

Abolitionist Benjamin Drew traveled to Canada and interviewed freedom seekers, resulting in an 1856 book (Ohio History Connection)

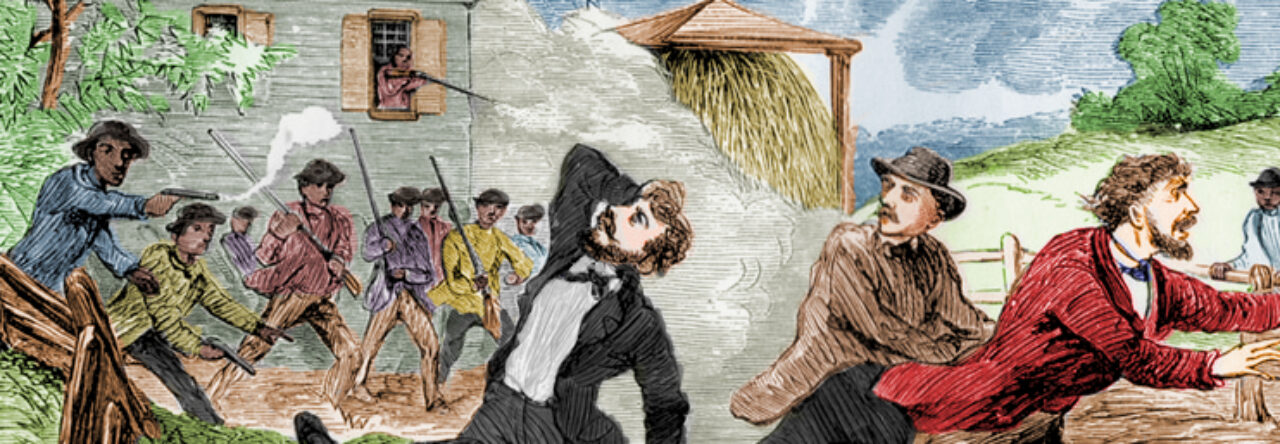

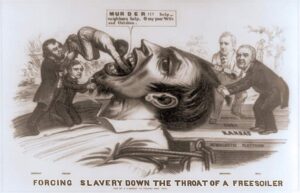

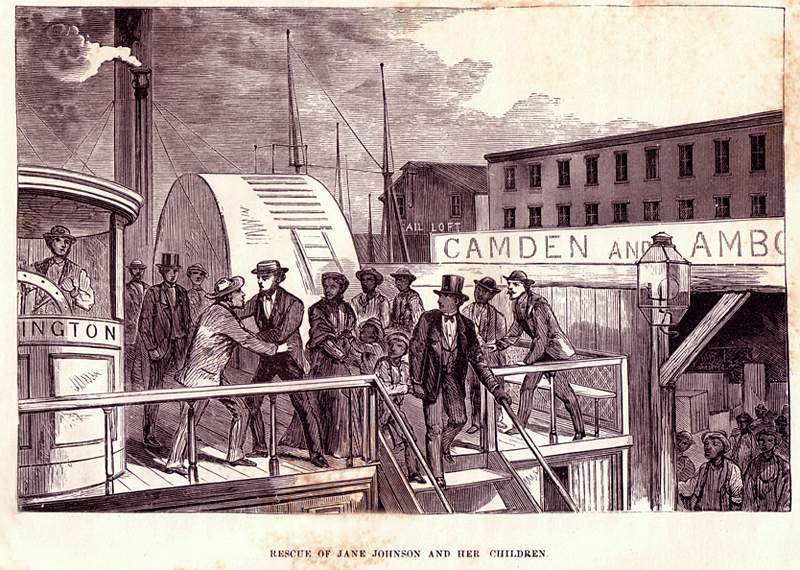

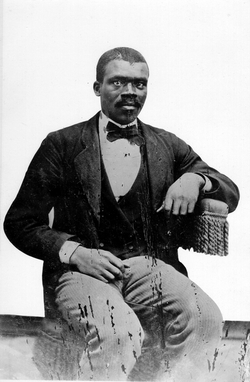

THE colored population of Upper Canada, was estimated in the First Report of the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada, in 1852, at thirty thousand. Of this large number, nearly all the adults, and many of the children, have been fugitive slaves from the United States; it is, therefore, natural that the citizens of this Republic should feel an interest in their fate and fortunes. Many causes, however, have hitherto prevented the public generally from knowing their exact condition and circumstances. Their enemies, the supporters of slavery, have represented them as “indolent, vicious, and debased; suffering and starving, because they have no kind masters to do the thinking for them, and to urge them to the necessary labor, which their own laziness and want of forecast, lead them to avoid.” Some of their friends, anxious to obtain aid for the comparatively few in number, (perhaps three thousand in all,) who have actually stood in need of assistance, have not, in all cases, been sufficiently discriminating in their statements: old settlers and new, the rich and the poor, the good and the bad, have suffered alike from imputations of poverty and starvation–misfortunes, which, if resulting from idleness, are akin to crimes. Still another set of men, selfish in purpose, have, while pretending to act for the fugitives, found a way to the purses of the sympathetic, and appropriated to their own use, funds intended for supposititious sufferers.

Such being the state of the case, it may relieve some minds from doubt and perplexity, to hear from the refugees themselves, their own opinions of their condition and their wants. These will be found among the narratives which occupy the greater part of the present volume.

Further, the personal experiences of the colored Canadians, while held in bondage in their native land, shed a peculiar lustre on the Institution of the South. They reveal the hideousness of the sin, which, while calling on the North to fall down and worship it, almost equals the tempter himself in the felicity of scriptural quotations.

The narratives were gathered promiscuously from persons whom the author met with in the course of a tour through the cities and settlements of Canada West. While his informants talked, the author wrote: nor are there in the whole volume a dozen verbal alterations which were not made at the moment of writing, while in haste to make the pen become a tongue for the dumb.

Many who furnished interesting anecdotes and personal histories may, perhaps, feel some disappointment because their contributions are omitted in the present work. But to publish the whole, would far transcend the limits of a single volume. The manuscripts, however, are in safe-keeping, and will, in all probability, be given to the world on some future occasion.

For the real names which appear in the manuscripts of the narratives published, it has been deemed advisable, with few exceptions, that letters should be substituted….

Related Essays