William and Ellen Craft pull off a race- and gender-bending escape from slavery, using masterful disguises to traverse the Deep South and reach freedom

Date(s): left Georgia on December 21, 1848, reached Philadelphia on December 25, 1848

Location(s): Macon, Georgia; Philadelphia; Boston; England

Outcome: Freedom

Summary:

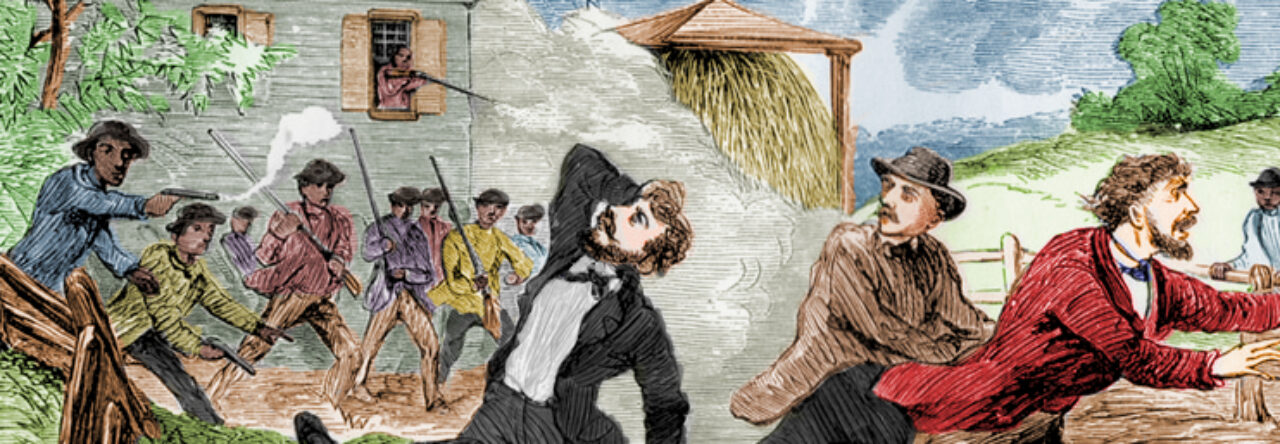

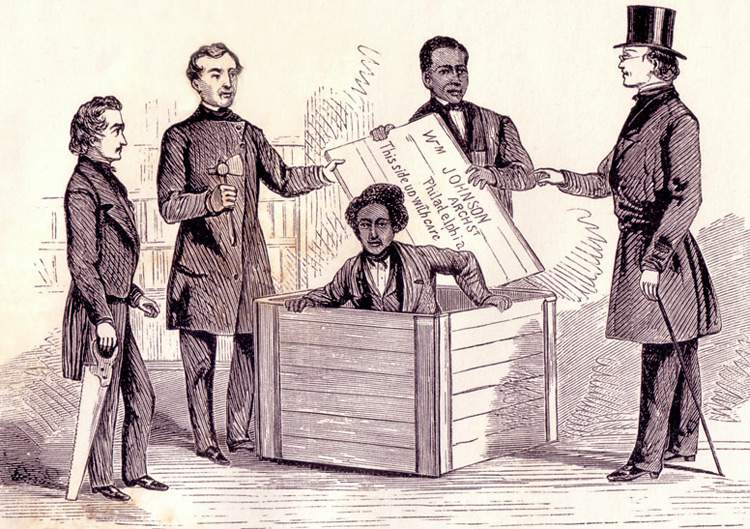

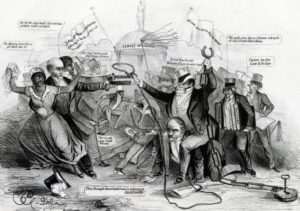

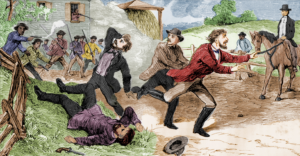

Ellen Craft (House Divided Project)

Enslaved couple William and Ellen Craft engineered a plan to deliver themselves (and their future children) from slavery in Georgia. William was unable to pass as white. However, Ellen was only one-quarter Black, and since she was frequently mistaken as a fully white woman, the couple hoped that it would be plausible for Ellen to act as William’s sickly male master while they crossed the Deep South. William gave his wife a more masculine haircut. Ellen immobilized her right arm in a sling and wrapped cloths around her face to avoid having to sign documents or speak. The Crafts traveled north by rail through multiple slave states, managing to avoid detection because of multiple strokes of good fortune. Still, the journey was stressful, and reaching Philadelphia on Christmas morning was the best gift either of the Crafts could have received. The couple moved to Boston under a month later, and settled into jobs as a cabinetmaker and seamstress, respectively. But pressure again began to mount two years later, when a group of slave catchers tracked the Crafts down to the home of Black abolitionists Lewis and Harriet Hayden. The Haydens asserted that they would rather blow their house up than allow the catchers to take the Crafts, and their determination shielded the Crafts until they were able to flee to England. While living in exile from the United States, William and Ellen honed their new literacy (introduced to them by Pennsylvania abolitionists) to publish their story, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom (1860). After the Civil War, the Crafts returned to Reconstruction-era Georgia and opened schools for freedpeople.

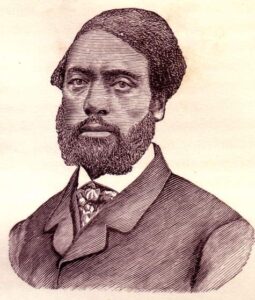

William Craft (House Divided Project)