Citation

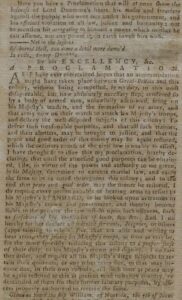

A Proclamation, November 7, 1775, FULL TEXT via Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Excerpt

Dunmore’s Proclamation (Gilder Lehrman Institute)

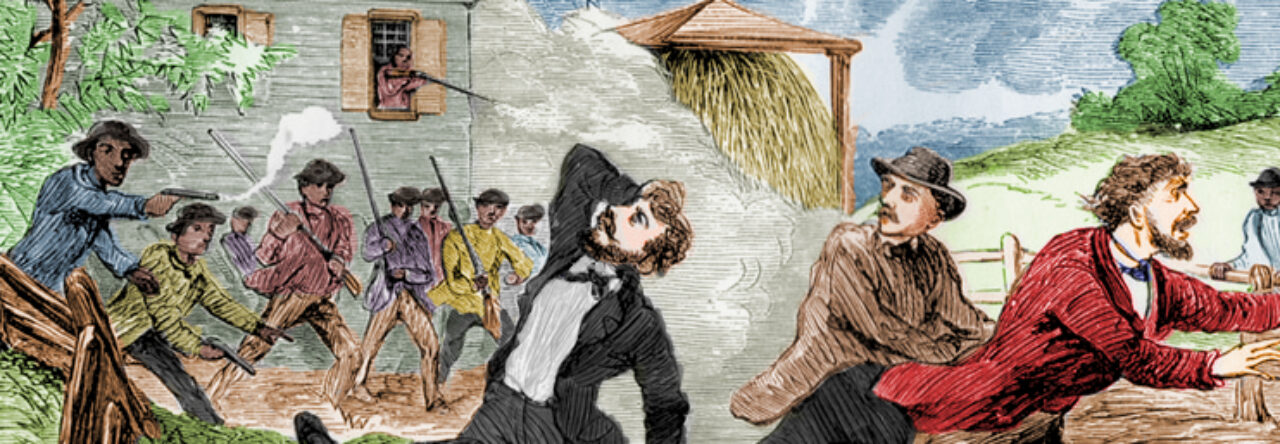

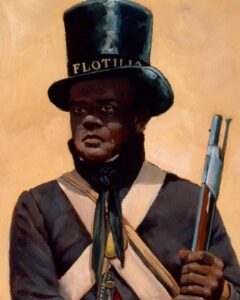

As I have ever entertained hopes that an accommodation might have taken place between Great-Britain and this colony, without being compelled, by my duty, to this most disagreeable, but now absolutely necessary step, rendered so by a body of armed men, unlawfully assembled, firing on his Majesty’s tenders, and the formation of an army, and that army now on their march to attack his Majesty’s troops, and destroy the well disposed subjects of this colony: To defeat such treasonable purposes, and that all such traitors, and their abetters, may be brought to justice, and that the peace and good order of this colony may be again restored, which the ordinary course of the civil law is unable to effect, I have thought fit to issue this my proclamation, hereby declaring, that until the aforesaid good purposes can be obtained, I do, in virtue of the power and authority to me given, by his Majesty, determine to execute martial law, and cause the same to be executed throughout this colony; and to the end that peace and good order may the sooner be restored, I do require every person capable of bearing arms to resort to his Majesty’s STANDARD, or be looked upon as traitors to his Majesty’s crown and government, and thereby become liable to the penalty the law inflicts upon such offences, such as forfeiture of life, confiscation of lands, &c. &c. And I do hereby farther declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining his Majesty’s troops, as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper sense of their duty, to his Majesty’s crown and dignity. I do father order, and require all his Majesty’s liege subjects to retain their quitrents, or any other taxes due, or that may become due, in their own custody, till such time as peace may be again restored to this at present most unhappy country, or demanded of them for their former salutary purposes, by officers properly authorized to receive the same.

Given on board the ship William, off Norfolk, the 7th of Nov.