Slaveholders’ attempt to punish abolitionists involved in Jane Johnson’s escape backfires, landing abolitionist Passmore Williamson in prison but making him an antislavery martyr

Date(s): escaped July 18, 1855

Location(s): Philadelphia

Outcome: Freedom

Summary:

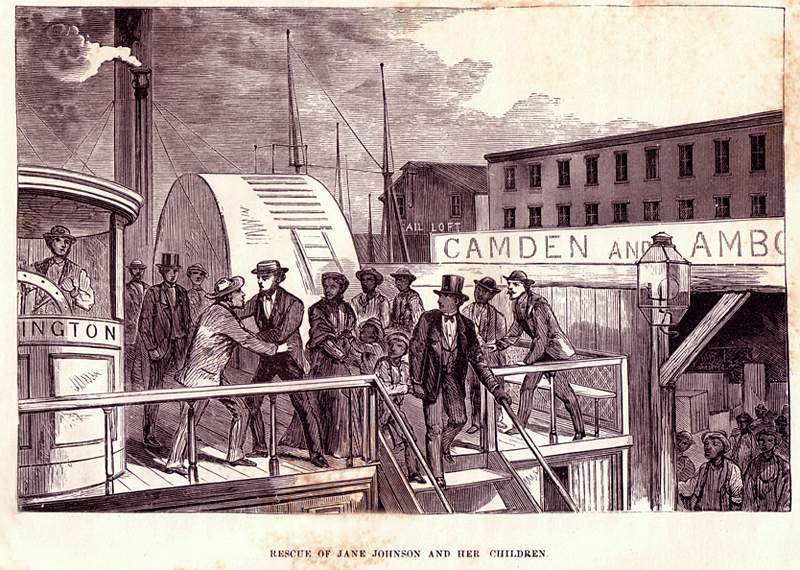

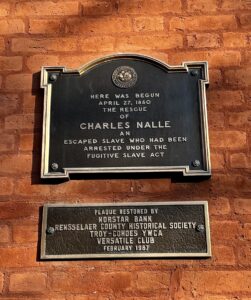

North Carolinian John Wheeler had just been appointed the new US ambassador to a rump proslavery government in Nicaragua, and he intended to bring three enslaved people along with him: Jane Johnson and her two sons, Daniel (aged around 10-11) and Isaiah (aged around six to seven). The diplomat planned to travel through Washington, DC and Philadelphia, en route to New York City, where he would board a ship for Nicaragua. But Wheeler knew that traveling through the North with enslaved people was risky. Many Northern states denied slaveholders the right of sojourn (to hold enslaved people as property while visiting), and the federal 1850 Fugitive Slave Act only applied to enslaved people who escaped, not those brought north with their slaveholder’s consent. As a result, Wheeler forbade Johnson from speaking to Black people in the Northern cities they were passing through. But Jane Johnson also understood that Northern state laws worked in her favor. Soon after arriving in Philadelphia, Johnson contacted Black hotel workers who alerted Philadelphia’s antislavery vigilance committee. Right before Wheeler’s party was set to disembark for New York, vigilance leaders Passmore Williamson and William Still boarded the boat and escorted Jane and her two children back to shore over Ambassador Wheeler’s angry protests. Unable to reenslave Johnson and her children, Wheeler and US authorities targeted the Underground Railroad activists who helped her escape. Wheeler pressed charges against Still and five Black dockworkers for assault and battery, but Johnson (now free by state law) returned to Philadelphia and testified on their behalf. Johnson’s deposition that she left willingly and was not forced by Still and others helped lead to the Black activists’ acquittal. Federal district court judge John Kane was unable to convict Passmore Williamson under the federal fugitive slave law, but did find the abolitionist guilty of contempt of court. Instead of deterring future Underground Railroad activism, however, Williamson’s three-month prison sentence for contempt of court made him a martyr for the movement.

Related Resources

Jane Johnson’s deposition reprinted in William Still, The Underground Railroad (1872), 94-95, [WEB]

Abolitionist Passmore Williamson’s account published as Narrative of the Facts in the case of Passmore Williamson (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, 1855), [WEB]

Cartoon depicting Johnson’s escape published as The Follies of the Age, Vive La Humbug! Lithograph. (Philadelphia, ca. 1855), [WEB]