Banner image: Theodor Kaufmann’s painting “On to Liberty” (1867) depicted the daunting and uncertain journey toward self-liberation (The Met)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

To understand the meaning of freedom, we must understand those who sought to claim it. Theirs was a story of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness set in motion. Freedom seekers, as they’ve come to be known, were daring agitators and powerful dreamers who undermined the system of slavery through escape, one step at a time.

To better understand their motivations, one needs only to seek out their testimony to discover why they made the treacherous journey. Narratives collected in Canada, from over 100 refugees from slavery, offer a glimpse into the minds of freedom seekers, many of whom had relocated there in the 1850s following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law. While Canada was not the chosen destination for the majority of freedom seekers, it nonetheless served as a powerful benchmark for those who would travel to the farthest reaches to secure their liberty.[1]

Benjamin Drew’s interviews provided direct testimony from freedom seekers (UNC / DocSouth)

Abolitionist Benjamin Drew brought together many of these stories in The Northside View of Slavery (1856). This extraordinary collection essentially provides the playbook of five key steps accessed by freedom seekers in pursuit of their reward: 1) Vision, the ability to see oneself as free; 2) Determination, possessing the will to pursue it; 3) Discernment, finding the way to achieve it; 4) Faith, channeling inner-strengths and higher powers; and 5) Transformation, the ability to reinvent oneself. These were the critical, determining factors of success for those who took to the road.

VISION

The first step to attaining one’s freedom was having a vision of what that freedom could be. Many freedom seekers recalled having such a dream long before they ever took to the road.

The first step to attaining one’s freedom was having a vision of what that freedom could be. Many freedom seekers recalled having such a dream long before they ever took to the road. “My idea of freedom during my youth,” recalled Reverend Alexander Hemsley, “was a state of liberty for the mind,–that there was a freedom of thought, which I could not enjoy unless I were free.”[2] For Henry Williamson it was “for the love of liberty.” He would not have left otherwise, he said. “I felt that I was better off than many that were slaves, but I felt that I had a right to be free.”[3]

Some could picture themselves in freedom but didn’t know where to find it or how to get there. Self-doubt, fear, and other counterforces kept many of these dreamers in check. John Atkinson spoke of the great difficulty in actuating such a dream: “A man who has been in slavery knows, and no one else can know, the yearnings to be free, and the fear of making the attempt. It is like trying to get religion, and not seeing the way to escape condemnation.”[4] Thomas Hedgebeth lamented that “a good many” enslaved “were so ignorant that they did not know any better, than to suppose that they were made for slavery, and the white men for freedom.”[5] These dreamers might have achieved such freedom—even within the confines of enslavement—had security of body and mind been guaranteed to them at home.

Harriet Tubman (House Divided Project)

Harriet Tubman, one of the informants, testified to a similar notion: “I grew up like a neglected weed,–ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it,” she said.[6] While in bondage, Tubman had made tremendous strides to improve the condition of herself and her family, and only made the risky decision to run when finally faced with her own impending sale. Only after reaching free soil did Tubman begin to fully realize her vision, which led her to return south to guide others to freedom so that they might achieve a similar dream.

DETERMINATION

Determination, the second step, was the ability to pursue one’s freedom. It bridged the gap between a dream of freedom and the will to move forward and find it. While many freedom seekers’ decision to run were sparked by cataclysmic events, such as family separations and especially harsh punishments, escape was not the domain of the Underground Railroad alone, and many excelled at this act of resistance before testing their luck on the road.

In slavery some perfected short-lived escapes—fast freedom if you will—living as maroons on the plantation outskirts to gain relief from life’s daily pressures. Others crisscrossed the plantation boundaries undetected to reunite with family and friends and developed measures for avoiding capture from those who would curtail their movements. Francis Henderson, who fled from Washington DC, recalled one method used to rout patrollers. “I have known the slaves to stretch clothes lines across the street, high enough to let the horse pass, but not the rider: then the boys would run, and the patrols in full chase would be thrown off by running against the lines.”[7]

A freedom-seeking couple fends off dogs in Richard Ansdell’s “The Hunted Slaves,” 1862 (Smithsonian)

Others evaded blood-sniffing dogs with homemade potions applied to their feet and legs to cover their scent and throw their pursuers from the trail. Red pepper and wild onions were but some of the ingredients used, as well as dirt grabbed up from moldering graves and turned into a paste.[8] Such test flights relied on ingenuity and helped these escape artists in training to hone their survivalist skills, while providing dry runs for future escapes that might carry them to a lasting freedom.

When the moment arrived to make the long journey, each departure set in motion a powerful disruption from the big house down to the quarter, igniting rage among enslavers while providing encouragement—and a vision of freedom—to those left behind. If a freedom seeker successfully passed through the gauntlet of bloodhounds, slave catchers, and natural elements, they soon discovered uncertainty to be the next obstacle in their way.

After being sold from his home in Virginia—a mere day’s walk from the Pennsylvania line—William Grose found himself shipped south to a new owner in New Orleans. William bided his time there, for a year, before picking up “spunk” and starting for Canada, but eventually succumbed to a creeping fear as he traveled the 1,000 mile-long path alone. “All the way along, I felt a dread–a heavy load on me all the way” he said. “I would look up at the telegraph wire, and dread that the news was going on ahead of me.” It wasn’t until later, when he came to a place where the telegraph wires were down, that his anxiety gave way to relief, his spirits rallied and with help gained along the way he made it safely to Canadian soil.[9] Determination kept William and other freedom seekers fixed to their goal, serving as an inner-compass of sorts when they risked veering off their course. Only after activating this power could they access assistance they would need for the trek, some of which appeared to the naked eye, while some required a closer look.

DISCERNMENT

In the southern states the path north was impromptu, more so than in the border regions. Here the road revealed itself in increments, rather than providing all-access passage to its applicants. More of a puzzle than pre-formed route, travelers pieced it together step by step, making discernment the pivotal third key in effecting successful escapes.

While assistance was critical to the success of most flights, it was sporadic and unreliable at times. Some moments it appeared in human form, at other times from the natural realms, leaving freedom seekers to unlock these riddles themselves. The North Star’s navigational power, for instance, was common knowledge in the plantation quarter and many travelers reported having followed its lead, sometimes with mixed results. One anonymous informant tracked the star by nights, but when it became too dark to see its light he felt around trees instead for the “long-growing moss” to redirect his way.[10] Edward Hicks devised an alternate solution; placing a stick by the side of the road each night, pointing it in the direction he wanted to resume the next evening in the event the sky was overcast.[11]

While assistance was critical to the success of most flights, it was sporadic and unreliable at times.

Work-arounds like these were critical when facing unexpected obstacles, which often appeared mid-flight and required quick thinking to circumvent. Charles Peyton Lucas found this out for himself as he led a party of men through Virginia and suffered great deprivations along the way from exposure, dehydration, and hunger. At times, the troop succumbed to desperate measures such as drinking from puddles left by horse tracks in the road. Another time they reached the Potomac River and puzzled as to how to get across. According to Lucas “whether to wade it, swim it, or get drowned, we knew not.” Finally, the group “waded and swam” as he recalled “changing our ground as the water deepened. At last we reached the opposite bank in Maryland: we merely stopped to pour the water out of our boots.”[12]

Freedom seekers like Lucas fared best while traveling in groups and playing off of one another’s strengths. Their ability to shift with the currents—in both literal and figurative terms—reveals flexibility as one of their more highly developed skills. While some tossed their fate to the winds, others put their trust in powers unseen. Vision, determination and discernment put many freedom seekers well on their way, but it took faith—perhaps the most powerful force—to get them over the finish line.

FAITH

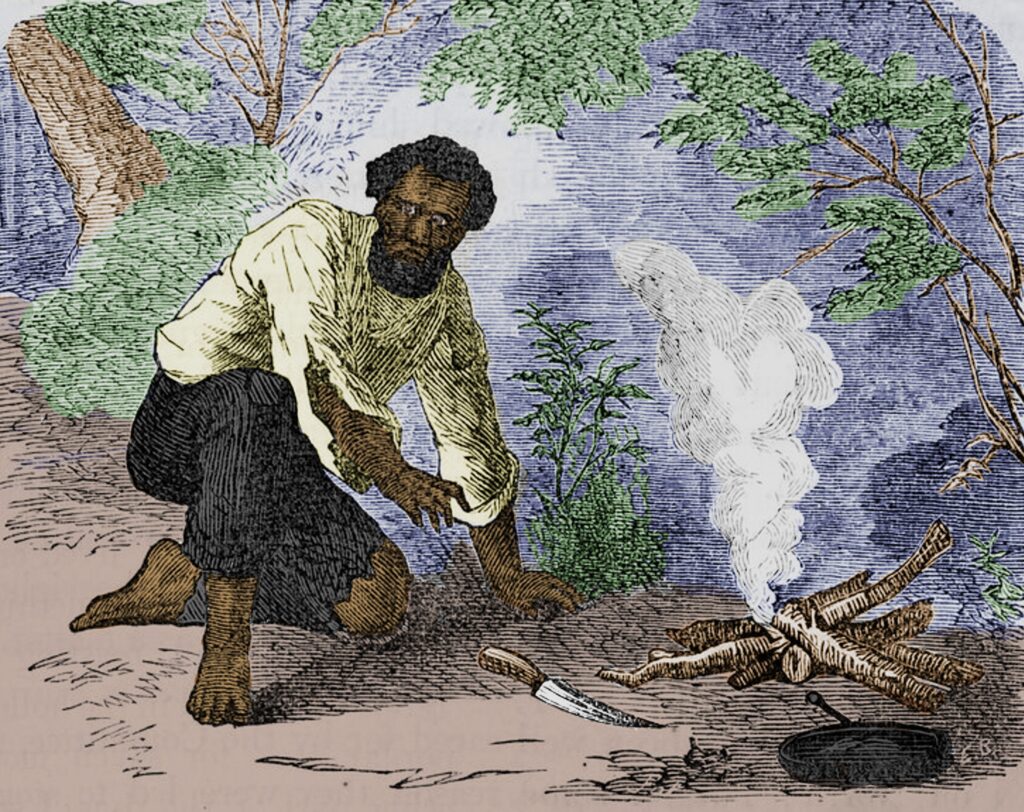

John and Eliza Little, who escaped from Jackson, Tennessee to Canada in the 1830s, best exemplify this vital trait, and its application on the road. Their journey started off tenuously. They traveled by nights and slept by days. They sheltered in barns, stole blankets for warmth, and ate raw ham “like a dog” for lack of fire to cook it. They set out in search of “Ohio State” but changed course for Canada instead. But where that was or how to get there the Littles could not say.[13]

At first the couple kept out of sight for fear of being exposed, but in time opened up to strangers, Black and white, who pointed them in the right direction. Through their faith in each other they kept to the course and began to hit their stride, taking bigger risks to reap bigger rewards while acquiring greater confidence. At nights they alternately lit fires for warmth, to cook food with, and to drive away insects, then put out the fires when danger approached, then lit them again when the coast was clear. When stopping to rest they took turns keeping watch—one sleeping, one remaining awake—with Eliza insisting if this had not been done, “we would not have reached Canada.”[14]

“Living in a cave” from William Still, Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Gabe Pinsker (House Divided Project)

The Littles grew stronger, bolder, braver and more daring than they ever had been back at home and evolved into a formidable force with every turn of the road. One time after being accosted by a white man, the couple defiantly stood their ground, not running, but threatening him with bodily harm as he headed off for reinforcements. Instead of retreating in the opposite direction, Eliza recalled “We followed him as he went the same way we were going, and kept as close to him as we could: for, if the man got hounds he would start them at the place where he had seen us; and coming back over the same route with hounds, horses, and men, would kill our track, and they could not take us.”[15]

Eliza, a house servant, whose hands had once blistered when she was suddenly set to field work, now faced grueling realities on the road with an air of conviction and ease. “There was something behind me driving me on” she said, but what it might be she did not know—whether trust in herself or a higher power Eliza answered the call. She went from being stricken with fear the first time she forded a stream, to boldly crossing the Ohio Bottoms straddling a log with the couple’s possessions strapped to her back. When her shoes gave out, she borrowed John’s. When those gave out, they both went barefoot, traveling hundreds of miles—swollen ankles and all—until they finally set foot in Chicago. As Eliza recalled it, somewhat nonchalantly, “I got to be quite hardy–quite used to water and bush-whacking; so that by the time I got to Canada, I could handle an axe, or hoe, or any thing (sic).” [16]

TRANSFORMATION

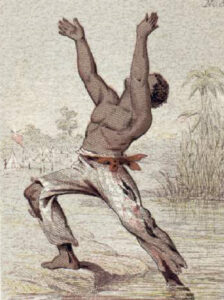

A wartime depiction of a freedom seeker’s liberation (House Divided Project)

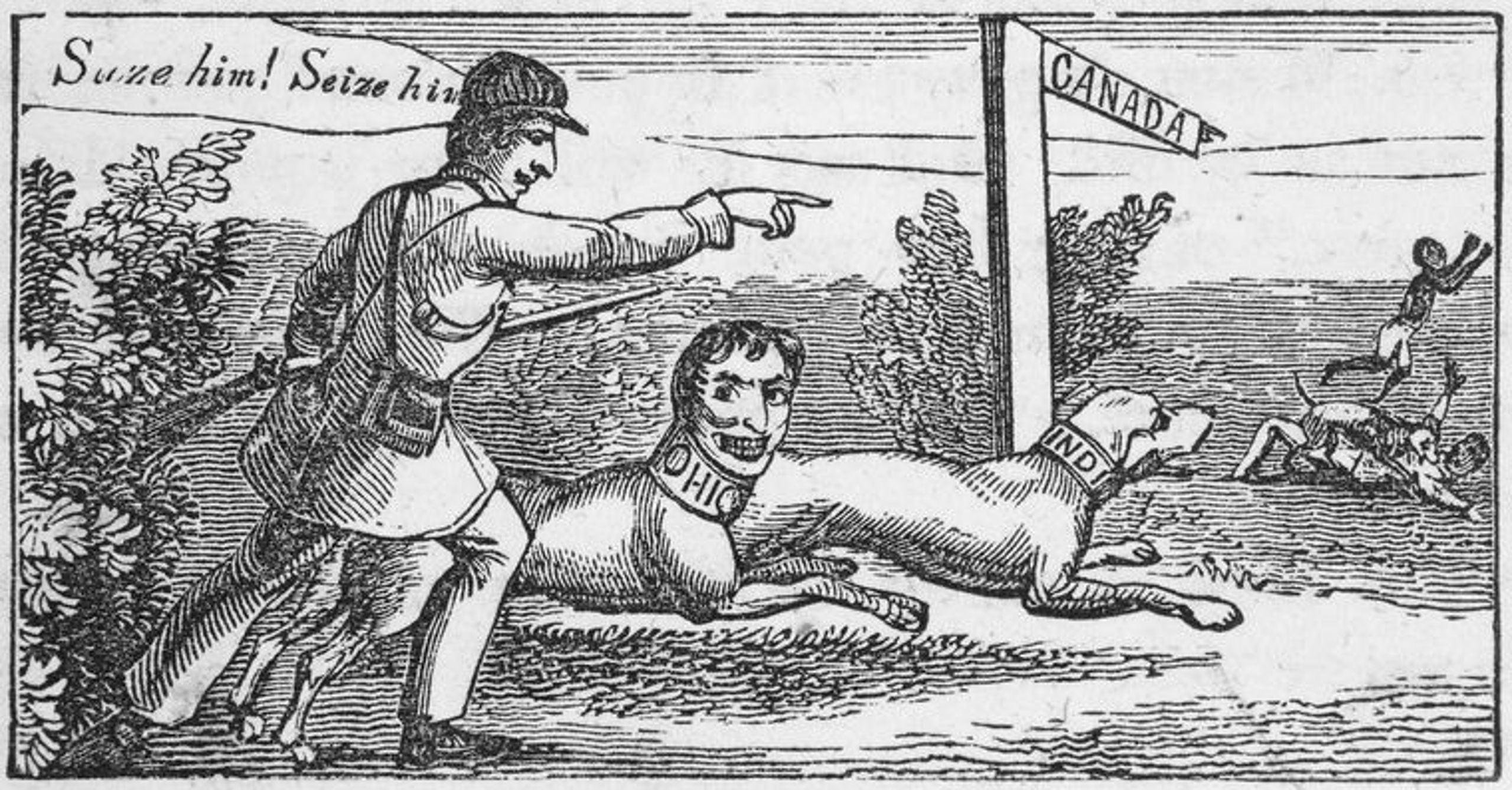

Transformation, the fifth and final key, was the reward for making it to freedom where the end of the line for those who reached Canada meant the end of the hunt and the threat of being returned to the South. Many experienced their first steps on free soil as a kind of rebirth. Some changed their names, casting off old personas, and reinventing themselves.

Reverend Alexander Hemsley claimed a full seroconversion from his relocation to Canadian soil. “Now I am a regular Britisher. My American blood has been scourged out of me; I have lost my American tastes; I am an enemy to tyranny.”[17] Conversely Ben Blackburn embraced his new homeland of Windsor, Ontario through the lens of the American dream. “I got here last Tuesday evening, and spent the Fourth of July in Canada. I felt as big and free as any man could feel, and I worked part of the day for my own benefit.”[18]

While most arrived with hopes for a new beginning, others were irrevocably chained to the past, and longed for their homes in the South and desired to be there with family once more. Harriet Tubman spoke stoically of what freedom in the North had both given and taken away. “Now I’ve been free, I know what a dreadful condition slavery is. I have seen hundreds of escaped slaves, but I never saw one who was willing to go back and be a slave. I have no opportunity to see my friends in my native land,” she lamented. “We would rather stay in our native land, if we could be as free there as we are here.”[19]

But the Littles, now many years on in Canada, made no mention of kin left behind, nor of any desire to return. Said John, “If there is a man in the free States who says the colored people cannot take care of themselves, I want him to come here and see John Little,” reflecting on his many achievements.[20] Eliza too was unequivocal in her contentment with Canada. “We have horses and a pleasure-wagon, and I can ride out when and where I please, without a pass. The best of the merchants and clerks pay me as much attention as though I were a white woman: I am as politely accosted as any woman would wish to be.”[21]

Upon first arriving in Queen’s Bush, Ontario, the couple found nothing before them but wilderness. They rolled back the forest, improved the land and amassed wealth and standing in their community, while transforming their adopted country in the midst of transforming themselves.

Slaveholders grew increasingly enraged that thousands of American freedom seekers were able to make their way to Canada (NYPL)

FREEDOM

In the end the Underground Railroad was a human effort, not merely an allusion of steam and steel, but a juggernaut of sinew and soul propelling its passengers to untold rewards.

In the end the Underground Railroad was a human effort, not merely an allusion of steam and steel, but a juggernaut of sinew and soul propelling its passengers to untold rewards. Self-liberators traveled, not merely for freedom but, with self-redemption in mind; a chance prove their worth, to reinvent themselves, and to reorder their place in world.

Vision, determination, discernment, and faith brought these dreamers to the threshold of liberty. Transformation—the final step—enabled them to walk through the door. Freedom, whatever or wherever it was, more than anything helped self-liberators open their eyes. Or as Mrs. Isaac Riley said of the journey to freedom “There we were in darkness,–here we are in light.”[22]

Further Reading

- Prince, Bryan. A Shadow on the Household: One Enslaved Family’s Incredible Struggle for Freedom. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2009.

- Larson, Kate Clifford. Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero. New York: Ballentine Books, 2003.

- Siebert, Wilbur H. The Underground Railroad From Slavery to Freedom. New York: MacMillan, 1898.

Discussion Questions

Theodor Kaufmann, “On To Liberty” (1867) (The Met)

- Which stage from Anthony Cohen’s “playbook” for liberation outlined in this essay do you imagine might be visualized here in this famous painting “On To Liberty” from Theodor Kaufmann?

- Why is it so important to try to understand the Underground Railroad from the perspective of freedom seekers? Yet why is so challenging to do so?

- As Cohen emphasizes, the Underground Railroad was more of a “puzzle” for freedom seekers than a fixed journey. How might that realization affect how we describe their relationship with the network that sometimes supported their escapes, especially as they entered free states or free countries such as Canada or Mexico?

Citations

[1] Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery: The Refugee (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856), Retrieved from https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/drew/drew.html

[2] Drew, 33.

[3] Drew, 134.

[4] Drew, 43.

[5] Drew, 277.

[6] Drew, 30.

[7] Drew, 156-157.

[8] Drew, 186, 263-264.

[9] Drew, 82-86.

[10] Drew, 283.

[11] Drew, 261.

[12] Drew, 107-108.

[13] Drew, 212-14.

[14] Drew, 228-233.

[15] Drew. 229.

[16] Drew, 221, 225, 228, 233.

[17] Drew, 39.

[18] Drew, 333.

[19] Drew, 30.

[20] Drew, 197-224.

[21] Drew, 216-219, 233.

[22] Drew, 301.

Author Profile

ANTHONY COHEN is the creator of the Menare Foundation, a national non-profit that is dedicated to the preservation of Underground Railroad history, historic sites and environments, and the creation of vibrant educational programs. He received his bachelor’s degree in American Studies from American University. As part of his research, Cohen has walked the Underground Railroad on multiple occasions, the first time traveling over 1,200 miles by foot, boat, and rail. His journey caught the attention of numerous radio, television, and print sources such as C-SPAN and the Washington Post. He has served as a consultant to the National Parks Conservation Association, Maryland Public Television and NASA, among others, and trained Oprah Winfrey for her role as Sethe in the motion picture Beloved (1998).

ANTHONY COHEN is the creator of the Menare Foundation, a national non-profit that is dedicated to the preservation of Underground Railroad history, historic sites and environments, and the creation of vibrant educational programs. He received his bachelor’s degree in American Studies from American University. As part of his research, Cohen has walked the Underground Railroad on multiple occasions, the first time traveling over 1,200 miles by foot, boat, and rail. His journey caught the attention of numerous radio, television, and print sources such as C-SPAN and the Washington Post. He has served as a consultant to the National Parks Conservation Association, Maryland Public Television and NASA, among others, and trained Oprah Winfrey for her role as Sethe in the motion picture Beloved (1998).

Related Works and Appearances by Anthony Cohen

- Traveling the Long Road to Freedom, One Step at A Time (Smithsonian, 1996)

- The Slavery Experience (CSPAN, 2010)

- Experiential History and the Underground Railroad (Adkins Arboretum, 2022)