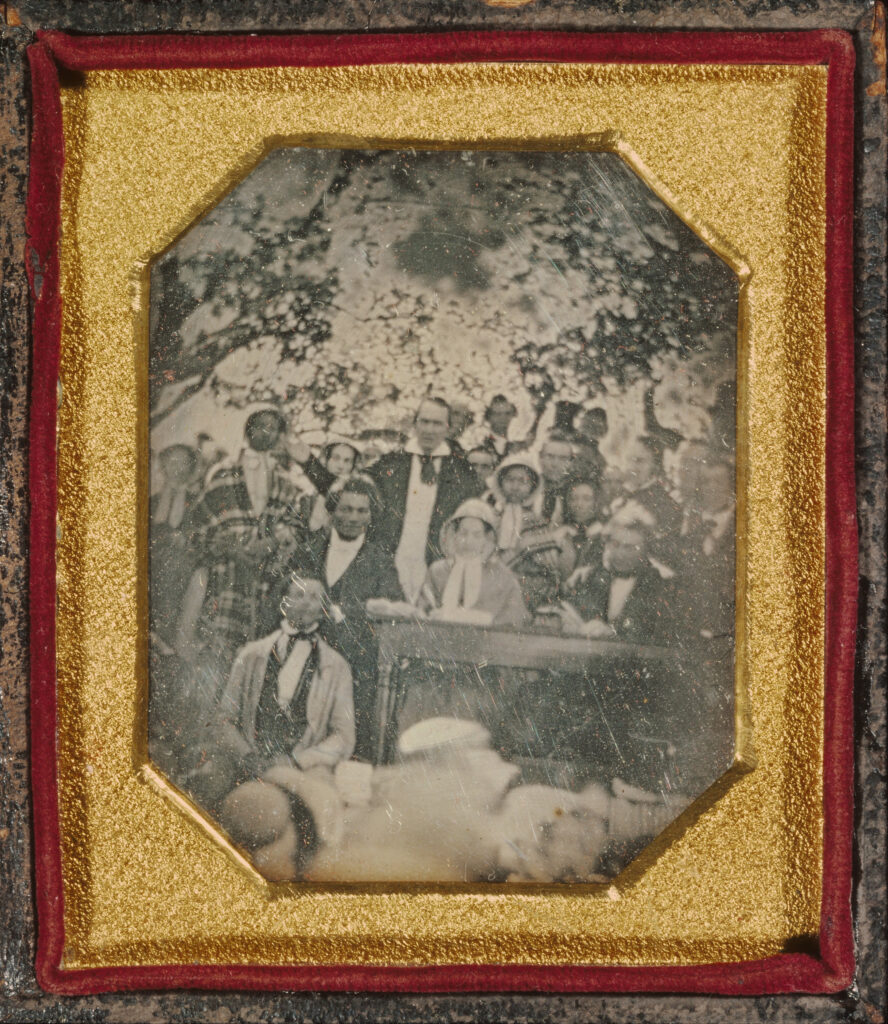

Banner image: In August 1850, abolitionists met at Cazenovia, New York to protest the proposed Fugitive Slave bill. Participants included Frederick Douglass (seated), Gerrit Smith (standing behind the table), and freedom seekers Mary and Emily Edmonson (standing beside Douglass, both wearing plaid). (Google Arts & Culture)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

The fugitive slave clause of the US Constitution guaranteed slaveholders the right to recapture enslaved people who escaped across state lines, regardless of the laws of the state to which they escaped. There had been no need for such a clause in the Articles of Confederation because slavery was legal in all 13 of the American colonies that declared their independence in 1776. Until then, the common law right of recaption ensured that a fugitive was legally subject to recapture no matter which colony he or she escaped to. But by the time the delegates gathered in Philadelphia for the constitutional convention 11 years later, the situation had changed. Slavery was being abolished throughout New England and, perhaps most threateningly, in the large state of Pennsylvania—which shared borders with five states where slavery was still legal. Moreover, even as the delegates were thrashing things out in Philadelphia, the Confederation Congress meeting in New York passed the Ordinance of 1787 or Northwest Ordinance, banning slavery from the northwest territories and, as if in compensation, incorporating the first iteration of the fugitive slave clause. Abolition had created a problem: merely crossing a state or territorial border could bring a fugitive slave into a legal world where freedom rather than slavery was presumed. The political implications were potentially disruptive and so a fugitive slave clause was deemed necessary.

Abolition had created a problem: merely crossing a state or territorial border could bring a fugitive slave into a legal world where freedom rather than slavery was presumed.

Yet almost immediately, it became clear that northern and southern states had a different understanding of what the new Constitution required. In 1788 Pennsylvania passed the first of dozens of northern personal liberty laws protecting Black residents accused of being fugitives. A few years later, in 1793, Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Act, seemingly signaling the North’s acceptance of the constitutional compromise. By the late 1790s, however, as more and more slaves from southern states escaped into northern states, and as free Black communities emerged to attract and harbor freedom seekers, southerners in Congress called for amendments to strengthen the 1793 statute—amendments which northern congressmen consistently voted down. Nevertheless, by authorizing southern masters to come into the free states and claim their escaped slaves without guaranteeing them due process rights, the 1793 act created the potential for legal and political conflict whenever an enslaved person escaped into a free state.

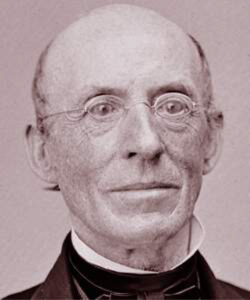

Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison helped promote ex-slave orators such as Frederick Douglass (House Divided Project)

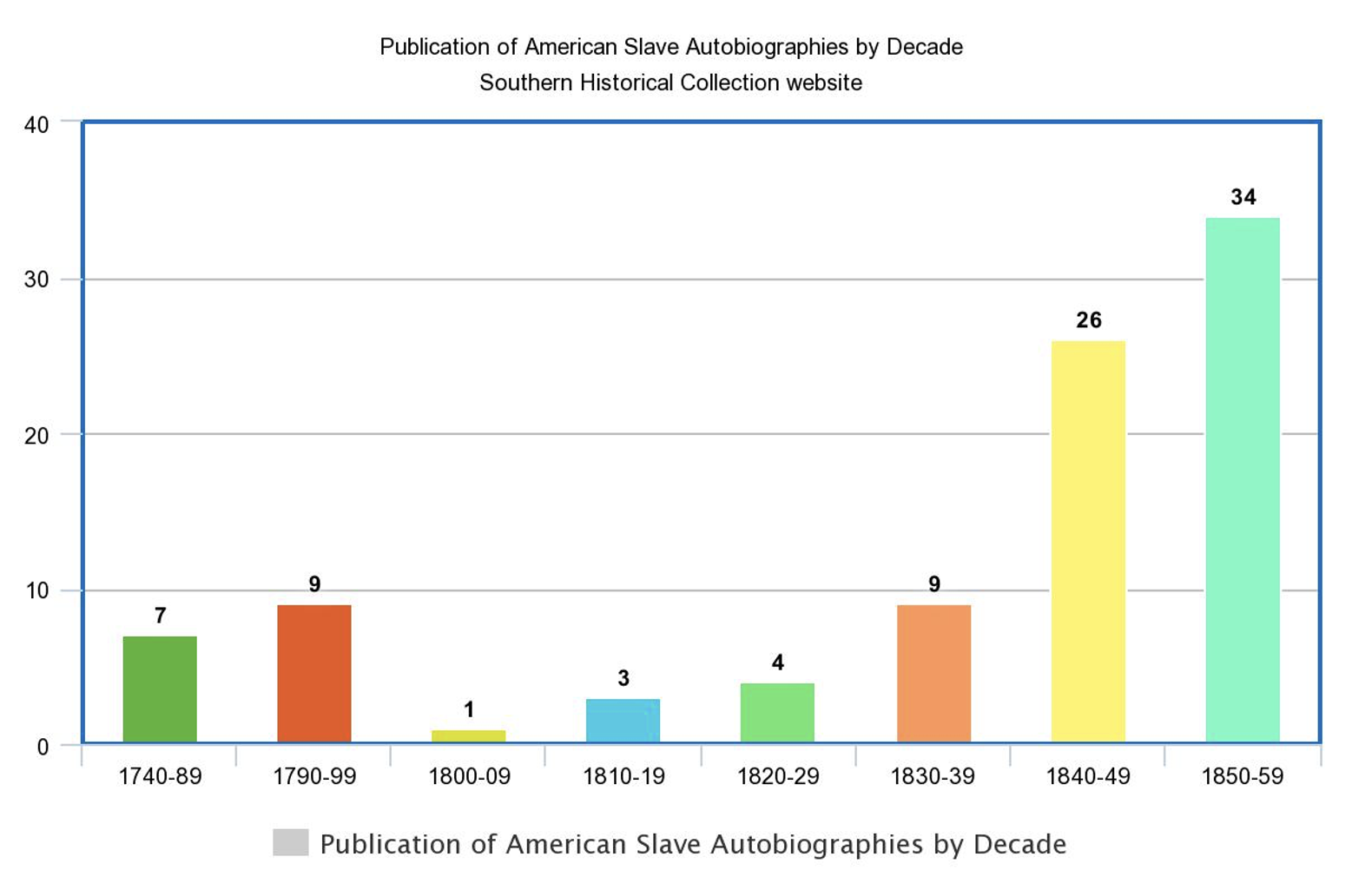

Political conflict accelerated with the rise of radical abolitionism in the 1830s. Among other things, abolitionists actively solicited and published the autobiographies of fugitive slaves, not only exposing the horrors of slavery, but also highlighting the dramatic details of their escapes. Antislavery activists had been sponsoring the publication of such narratives at least since the campaign to abolish the slave trade in the late 1700s. Drawing on that precedent, abolitionists in the late 1830s significantly expanded the number of ex-slave autobiographies they published, part of a deliberate campaign to promote sympathy for the antislavery movement by building sympathy for freedom seekers. These autobiographies are important sources for documenting the experience of slavery, but they were also politically significant because they were published as propaganda—factually accurate as far as we can tell, and for that reason all the more effective as propaganda. Once readers encountered the fugitive’s story “from his own lips,” the editors of one such narrative explained, it “would not be necessary again, for one year at least, to exhort them to active, self-denying effort for the slave.”[1] That was the point.

The efficacy of the propaganda campaign is hard to judge, but by the 1840s fugitive slaves were clearly becoming a significant issue in national politics. The Supreme Court ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) that the federal government was exclusively responsible for enforcing the constitution’s fugitive slave clause. States and localities could assist in renditions, but they were not required to do so. Northern states responded with a raft of new personal liberty laws withholding state and local support for slaveholders trying to capture their escaping slaves. The conflict over fugitive slaves became headline news in 1848 when 77 enslaved people in Washington, DC boarded the Pearl schooner and attempted one of the largest mass escapes in American history. Though the escape was foiled, it provoked a sharp debate on the floor of Congress. As antislavery representatives demanded due process rights for the captives, proslavery congressmen demanded a more effective fugitive slave law.

On January 24, 1850, South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler introduced a bill strengthening federal enforcement powers. New York Senator William Seward responded to Butler four days later with an alternative—a series of amendments to the 1793 law that would guarantee jury trials and habeas corpus to accused fugitives, in effect a federal personal liberty law.[2] Maryland Senator Thomas Pratt denounced Seward’s jury trial amendment as “a practical denial of the whole right of the slaveholder over his slave, if he get beyond the jurisdiction of his own State; because everybody knows,” Pratt continued, “the honorable Senator from New York himself knows” that fugitive slaves were being “discharged” by New York courts on the flimsiest of pretexts. “[O]f all the subjects doing harm at the South,” Pratt added, “the escape of fugitive slaves is doing the most harm,” and was “the most calculated to excite the public mind.”[3]

The fierce debates over the Compromise of 1850 lasted for months (US Senate)

The heated discussion of Butler’s bill takes up 30 pages of the Congressional Globe—90 large columns of very small print. After Seward’s attempt to add due process rights to the 1793 law had failed, northern senators across the political spectrum —from conservatives such as Daniel Webster and Robert Winthrop to antislavery radicals such as John Hale and Salmon Chase— proposed or endorsed similar amendments requiring jury trials and habeas corpus in the proposed 1850 law. Every one of those amendments was beaten back even though northern congressmen voted against the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 by a two-to-one margin. The final version of the enhanced enforcement law squeaked to passage thanks to the minority of northern supporters who voted with a virtually unanimous South.

The reaction across the North was immediate and intense. Weeks after the law was passed the abolitionist minister Theodore Parker thwarted slave catchers and with the help of a local vigilance committee spirited Georgia runaways William and Ellen Craft out of the country. Much of the resistance was the work of free Blacks. A few months after the Crafts’ escape, early in 1851, a group of Black men rescued a formerly enslaved waiter named Shadrach from federal marshals in Boston and got him to Canada. Later that same year, dozens of armed Black men and women shot and killed a Maryland slaveholder and wounded his son as they were trying to recapture their fugitive slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania. Across much of the North, vigilance committees sprang into action to thwart slave catchers. The federal government’s response to these and other violent incidents was so overbearing that it further politicized the issue. The spectacle of US troops sent to police the streets of Boston, and of US marines rushed to a small town in Pennsylvania, only served to intensify northern hostility to the law.

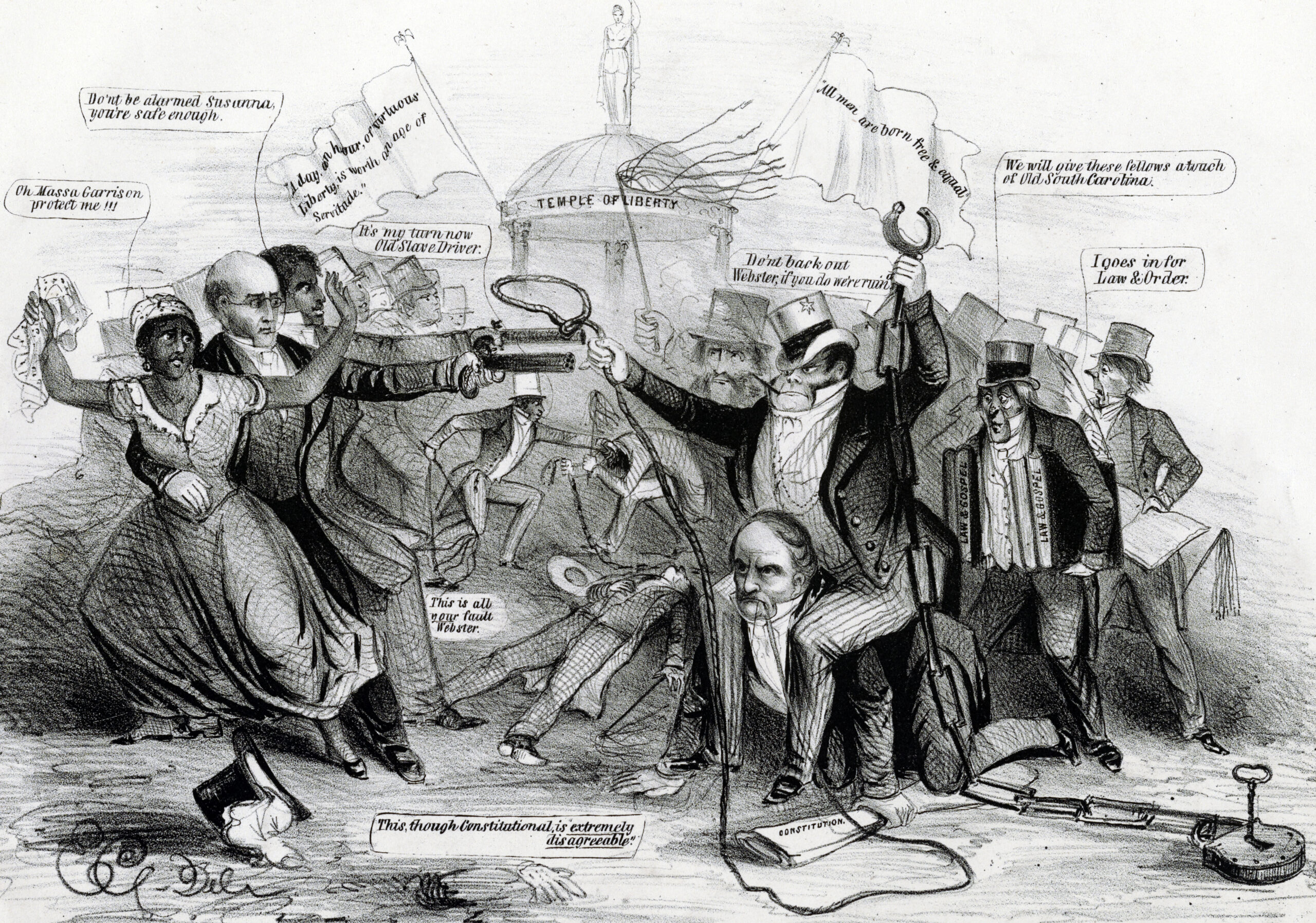

Northern political cartoon mocking the “Practical Illustrations” of the Fugitive Slave Law” (Library of Congress)

Despite violent incidents and spectacular crowds—50,000 people lined the streets of Boston to protest the 1854 rendition of Anthony Burns—one of the most significant and least appreciated means of preventing fugitives from being returned to slavery was the deliberate refusal to enforce the law in many northern communities. White sheriffs sometimes protected Black families who had lived in their communities for years. Lawyers (who were not supposed to be present) often gummed up the work of rendition hearings. Federal prosecutors could not find many jurors willing to convict those accused of violating the 1850 law. Northern state legislatures passed another round of personal liberty laws, guaranteeing habeas corpus and rights to jury trials for accused fugitives, prohibiting state and local police from enforcing the federal law, or banning slave catchers from using local jails to house fugitives.

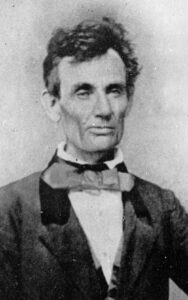

By the middle of the 1850s just about every politician identified with the new Republican Party was opposed to the Fugitive Slave Act. Some denounced it as unconstitutional. Others called for the law’s repeal. Still others, like Abraham Lincoln, wanted it revised to guarantee due process rights for accused fugitives. In 1854 Lincoln said he preferred a statute that “did not expose a free negro to any more danger of being carried into slavery, than our present criminal laws do an innocent person to the danger of being hung.”[4] He also objected to the “obnoxious” requirement that northern civilians be required to participate in fugitive slave renditions. In 1859 Lincoln warned that states which seceded from the Union would forfeit the constitutional right to secure the return of fugitives.[5] After he was elected in November 1860, Lincoln renewed his call for substantial revisions to the controversial 1850 law, revisions that would have amounted to a federal personal liberty law. Lincoln told fellow Republicans in private that he was willing to guarantee due process rights to suspected fugitives and restrict enforcement to federal officials, absolving northern states and civilians of any obligation to participate in the capture and return of fugitive slaves.[6]

By the middle of the 1850s just about every politician identified with the new Republican Party was opposed to the Fugitive Slave Act.

Lincoln’s secession winter proposal was more likely to inflame than to calm a South already aroused by his mere election. The very first item in South Carolina’s declaration justifying secession listed by name 14 northern states that had passed personal liberty laws. These laws, the Carolinians declared, “either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them.” Governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia endorsed secession on the ground that slave property was no longer safe within the Union. “Why remain?” he asked. “Will the Northern States repeal their personal liberty laws? No.” More to the point, the personal liberty laws were but a symptom of a much larger problem, as Alabama secession commissioner Stephen Hale explained to Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky. The Fugitive Slave Act “remains almost a dead letter upon the statute book,” Hale complained. “A majority of the Northern States, through their legislative enactments have openly nullified it, and impose heavy fines and penalties upon all persons who aid in enforcing this law…. The Federal officers who attempt to discharge their duties under the law, as well as the owner of the slave, are set upon by mobs, and are fortunate if they escape without serious injury to life or limb, and the State authorities, instead of aiding in the enforcement of the law, refuse the use of their jails, and by every means which unprincipled fanaticism can devise give countenance to the mob and aid the fugitive to escape.”[7]

Lincoln responded to these complaints by reiterating his proposal for a federal personal liberty law in his first inaugural address in March 1861. “There is much controversy about delivering up fugitives from service or labor,” he began. Everyone who swears an oath to the Constitution is of course swearing to uphold the fugitive slave clause. The question, Lincoln said, was how the clause was to be upheld. There was disagreement, for example, over who should enforce it. “Shall fugitives from labor be surrendered by national or by State authority?” Lincoln asked. “The Constitution does not expressly say.” But “in any law upon the subject,” he added, “ought not all the safeguards of liberty known in civilized and humane jurisprudence be introduced, so that a free man may not, in any case, be surrendered as a slave? And might it not be well, at the same time, to provide by law for the enforcement of that clause of the Constitution which guaranties that ‘The citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the several states?’” So long as the 1850 law remained on the books it should be obeyed, Lincoln said, but there are some laws that communities find so morally offensive that they will never be fully obeyed. He conceded that the fugitive slave law, “was as well enforced, perhaps, as any law can ever be in a community where the moral sense of the people imperfectly supports the law itself.”[8] And secession would only make the already lax enforcement of the fugitive slave law even “worse,” Lincoln warned, because “after the separation of the sections fugitive slaves, now only partially surrendered, would not be surrendered at all.”[9]

But “in any law upon the subject,” [Lincoln] added, “ought not all the safeguards of liberty known in civilized and humane jurisprudence be introduced, so that a free man may not, in any case, be surrendered as a slave?

From the moment some states began abolishing slavery in the late 1700s to the moment slave states began seceding from the Union in late 1860, fugitive slaves had created political problems that ultimately contributed to the coming of the Civil War.

Further Reading

- Oakes, James. The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution. New York: W.W. Norton, 2021.

Discussion Questions

Abolitionists at Cazenovia Convention (1850) (Google Arts & Culture

- How does this famous photograph from the August 1850 protest at Cazenovia, New York illustrate some of James Oakes’s key contentions about the evolving “politics of fugitive slaves”?

- What does Oakes mean when he writes that “Abolition had created a problem”?

- How did northern abolitionists use the fugitive slave crisis to further mobilize antislavery sentiment?

- What was Abraham Lincoln’s position on the fugitive slave crisis, according to historian James Oakes?

[1] “Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave,” The Emancipator, August 23, September 13, September 20, October 11, and October 18, 1838. Transcript available at http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/runaway/runaway.html

[2] Congressional Globe, 31 cong., 1st sess., p. 236. [January 28, 1850]

[3] Congressional Globe, 31 cong., 1st sess., p. 524. [March 24, 1850]

[4] Roy P. Basler, ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (9 vols; New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 2: 233n. Hereafter CW.

[5] CW, 3:454.

[6] CW 4: 156-7.

[7] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 4, v. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1900), 6.

[8] CW, 4:264.

[9] CW, 4:269.

Author Profile

JAMES OAKES is an American historian and Distinguished Professor of History and Graduate School Humanities Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. An alumnus of Baruch College, Dr. Oakes holds M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of California–Berkeley. Before coming to the Graduate Center, he taught at Princeton and Northwestern Universities. His pioneering books include The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (W.W. Norton, 2007); and Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865 (W.W. Norton, 2012). His most recent book is The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution (W.W. Norton, 2021).

JAMES OAKES is an American historian and Distinguished Professor of History and Graduate School Humanities Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. An alumnus of Baruch College, Dr. Oakes holds M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of California–Berkeley. Before coming to the Graduate Center, he taught at Princeton and Northwestern Universities. His pioneering books include The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (W.W. Norton, 2007); and Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865 (W.W. Norton, 2012). His most recent book is The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution (W.W. Norton, 2021).