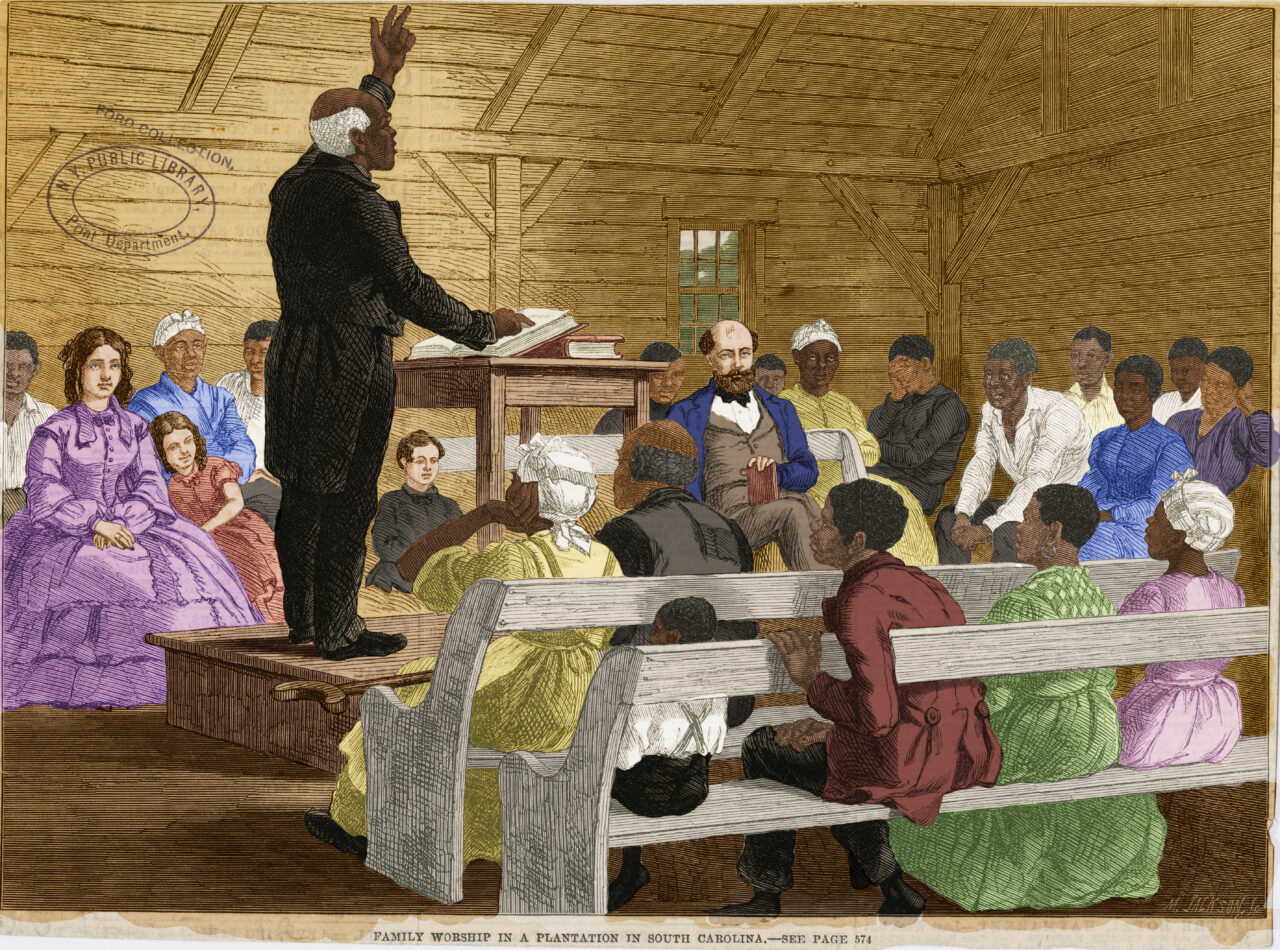

Banner image: Christian faith was at the center of both enslaved and free Black culture, and frequently helped connect escape networks. This illustration from the London Illustrated News in 1863 depicted a church meeting held on a South Carolina plantation, colorized by Gabe Pinsker (NY Public Library)

-

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

Activist African American denominations were often at the forefront of work on the Underground Railroad but in the background of written history. Among both African American and white protestant denominations, religion operated as one of the main pillars of the Underground Railroad. African Methodist denominations, particularly the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) almost universally supported the Underground Railroad. African American churches took the lead in the battle for abolition and in assisting freedom seekers. Underground Railroad activism operated inside denominations, churches, and congregations as well as through personal and individual actions, and inside the homes of abolitionists, Black and white. In Middletown, Connecticut, Pittsburgh, Louisville, St. Louis, and Detroit among many other towns and cities, the original Black church building often stood at or near the river’s edge to help with waterborne escapes. African Americans had been getting themselves out of slavery since the institution’s earliest days. Some of the most effective Underground Railroad activists were ministers who had once been held in slavery.

Activist African American denominations were often at the forefront of work on the Underground Railroad but in the background of written history.

Rev. Samuel Cornish co-founded Freedom’s Journal, the nation’s first Black newspaper (Wikipedia)

Blacks migrating from the east and south brought their religion with them as they pushed westward. After beginning in the east, African Methodism spread the length and breadth of the United States and into Canada by the outbreak of the Civil War. The AME denomination planted churches from New England to California and from the Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to New Orleans. Across the country, Black Baptists, too, were consistently involved with escapes from slavery. “Colored Presbyterian” churches and ministers, as they were generally called during the time period, were well-known for their Underground Railroad activism although Black Presbyterians did not organize themselves into a distinct denomination. Despite their connection to the Presbyterian denomination, African American ministers inside the religion such as Samuel Cornish voiced their powerful opposition to slavery. As a Presbyterian pastor in New York City, Cornish struck a journalistic blow for freedom by co-founding Freedom’s Journal in 1827, the first Black newspaper in the United States. Other African American ministers who supported the Underground Railroad such as Samuel Ringgold Ward and J. W. C. Pennington moved between denominations, at times pastoring a Colored Presbyterian congregation and at other times, a white Congregational church. While the minister moved from church to church, the layman remained behind to continue the Underground Railroad work of the congregation.

Congregations and ministers from white churches expressed their opposition to slavery though involvement in the antislavery movement, but put their works into action by supporting the Underground Railroad. To understand the religious nature of the Underground Railroad, we must understand that religion was also one of the main pillars in support of slavery. Actions of religious leaders working inside the Underground Railroad movement pushed against national law and public sentiment and were at times at odds with their own religious communities. White ministers were often enslavers and Blacks could not ascend to positions of importance or authority in any meaningful way in the major white denominations. Beyond Underground Railroad activism and abolitionist leanings, white churches tended to conform to prevailing patterns and racial attitudes of the time. Harriet Beecher Stowe railed against the inertia of white ministers and their religion. As historian Benjamin Quarles observes: “The churches broke no new ground in race relations.” A religious evolution had to take place to thrust white denominations toward a moral stand against slavery. Congregational minister and Black abolitionist, Samuel Ringgold Ward, observed:

The American Bible Society distributes no Bibles among the slave population. . . The American Sunday-school Union stands in precisely the same category. . . The several religious bodies, with their respective branches, of all denominations, except the Quakers and the Free-Will Baptists . . .are completely subject to the control of their slaveholding members. . . in Congregational New England the sons of Puritan sires are as guilty as the guiltiest enemies of the down-trodden slave. Such was . . . the case in 1839.[1]

It is simply not enough to say a participant was Methodist, Baptist or Presbyterian. Wesleyan Methodists, Free Will Baptists, and New School Presbyterians were Underground Railroad activists while Southern Baptists, Southern Methodists, and Old School Presbyterians clung to slavery. Schisms over slavery plagued and divided all three denominations. Furthermore, African American denominations or Black churches grew out of those main denominations.

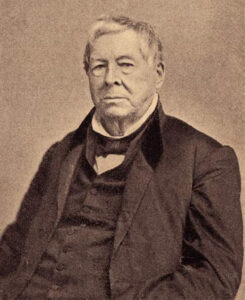

Quaker Thomas Garrett was a leading Underground Railroad agent from Delaware (House Divided Project)

The Society of Friends, better known as Quakers, has earned esteem for their early agitation against slavery and consistent involvement with the Underground Railroad. Their influence turns up in Underground Railroad story after story across the country. Quaker opposition to slavery and the sanctuary they provided were well known among freedom seekers. According to some sources, however, the Presbyterian church had the greatest number of non-Black participants in the Underground Railroad. Likewise, Congregationalists, who had their origins in New England spread their beliefs as the nation expanded westward and were also active Underground Railroad participants as they grew in number. Free Will Baptists were less well-known but no less fierce in their opposition to slavery. United behind the cause of freedom, Free Will Baptists ranked as an early, influential voice for abolition and as consistent workers on the Underground Railroad.

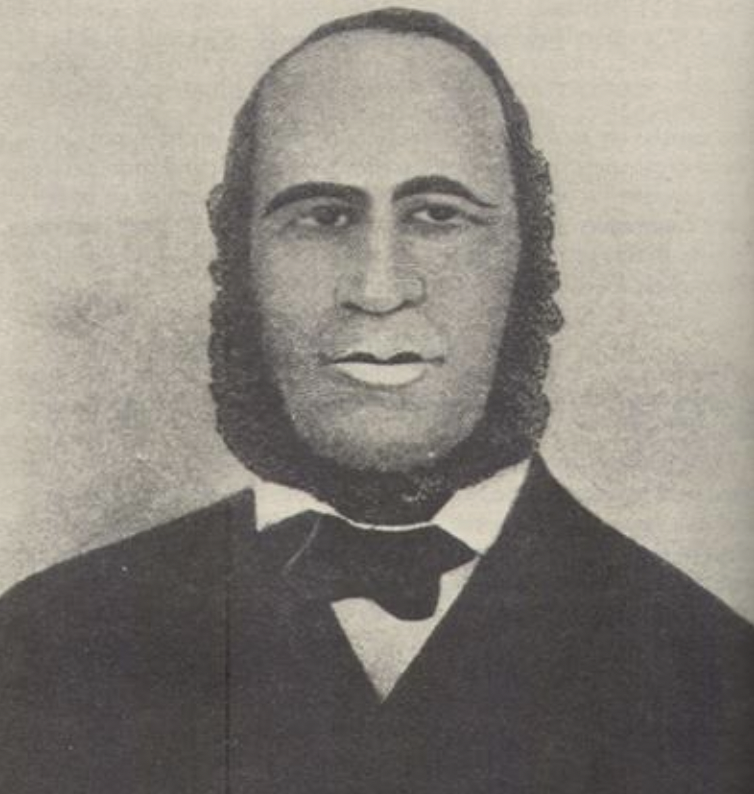

Identifying the religious affiliations of Underground Railroad operators and activists clarifies the religious distinctions that were in operation inside the movement. Denominational affiliations of Underground Railroad ministers were not regularly highlighted or recognized, which obscures the religious dynamics as well as the discord operating inside the movement. Black clergy were often lynchpins of abolitionism and the Underground Railroad. As slavery took deeper root in America across the 1800s, so too did religious opposition to it, often under the guidance of a charismatic leader. Of the African American abolitionists who founded or were early members of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1840, 10 were Black ministers and nine had ties to the Underground Railroad.[2] New York Congregationalist minister Charles Bennett Ray devoted so much time assisting freedom seekers that historians hardly thought of him as a minister at all. For most of the escapes in the New York area during his active years in the 1840s, Ray played some conspicuous role.

“New York Congregationalist minister Charles Bennett Ray devoted so much time assisting freedom seekers that historians hardly thought of him as a minister at all.” (Blackpast)

Firsthand, immediate knowledge of slavery fueled the activism and urgency of these men of God. Black ministers, many of whom had themselves escaped slavery, understood from experience the hellish evils of the practice. Andrew Bryan, ordained by the Baptist Church in 1788, founded one of the first African American churches of any denomination in Savannah, Georgia, after preacher George Liele gathered 30 congregants to form what was to become Savannah’s First African Baptist Church. The church had a long history of assisting freedom seekers before the advent of the Underground Railroad.

AME Rev. Jordan Early reported, “Our Church wherever established was called an abolition church, which made the slaveholders suspicious of its proceedings, and sometimes the members and local preachers were brought before courts of justice to answer for the absence of some slave who had made his escape.”[3] By 1846, magistrates in Missouri were openly questioning AME preachers about their involvement with the Underground Railroad. Future AME Bishop J. M. Brown faced arrest five times in New Orleans for his activities assisting freedom seekers.

During his family’s escape from Maryland, the future Presbyterian minister Henry Highland Garnett had been carried out of slavery when he could no longer walk on his own as an eight-year-old boy. Similarly, future Presbyterian minister Rev. Samuel Ringgold Ward also had been carried out of slavery in his mother’s arms as a 2-year-old. AME Zion Bishop Jermain Loguen of Syracuse, New York opened his home to freedom seekers and defied slave catchers and the law. Although men held most ministerial positions during the time of the Underground Railroad, the wives of these ministers and activists were deeply involved with their husbands. They provided food, shelter, and clothing and opened their homes as spaces of refuge for freedom seekers.

Other influential Black ministers found various ways to break slavery’s grip by buying their way out. Philadelphia’s John Gloucester of the First African Presbyterian Church bought his wife and four children out of slavery in 1807. Richard Allen, destined to become founder and the first bishop of the AME church, purchased his freedom and that of his brother during the Revolutionary War. John Berry Meachum first bought his own freedom, and then the freedom of his wife, children and father. While working as a minister in the relentless slave state of Missouri, Meachum, rather than acting as an Underground Railroad conductor, found a more careful but equally effective path to freedom. Whenever Meachum, pastor of the First African Baptist Church of St. Louis, heard of freedom seekers coming to St. Louis via the Mississippi River, he roused his congregation to raise the funds to purchase their freedom.[4] In this way, the congregation was able to secure the freedom of at least 20 freedom seekers. After Meachum’s death, his widow, Mary, was implicated in a famous case of eight or nine freedom seekers escaping from St. Louis to Illinois by crossing the Mississippi River in a skiff at what is now known as the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing.

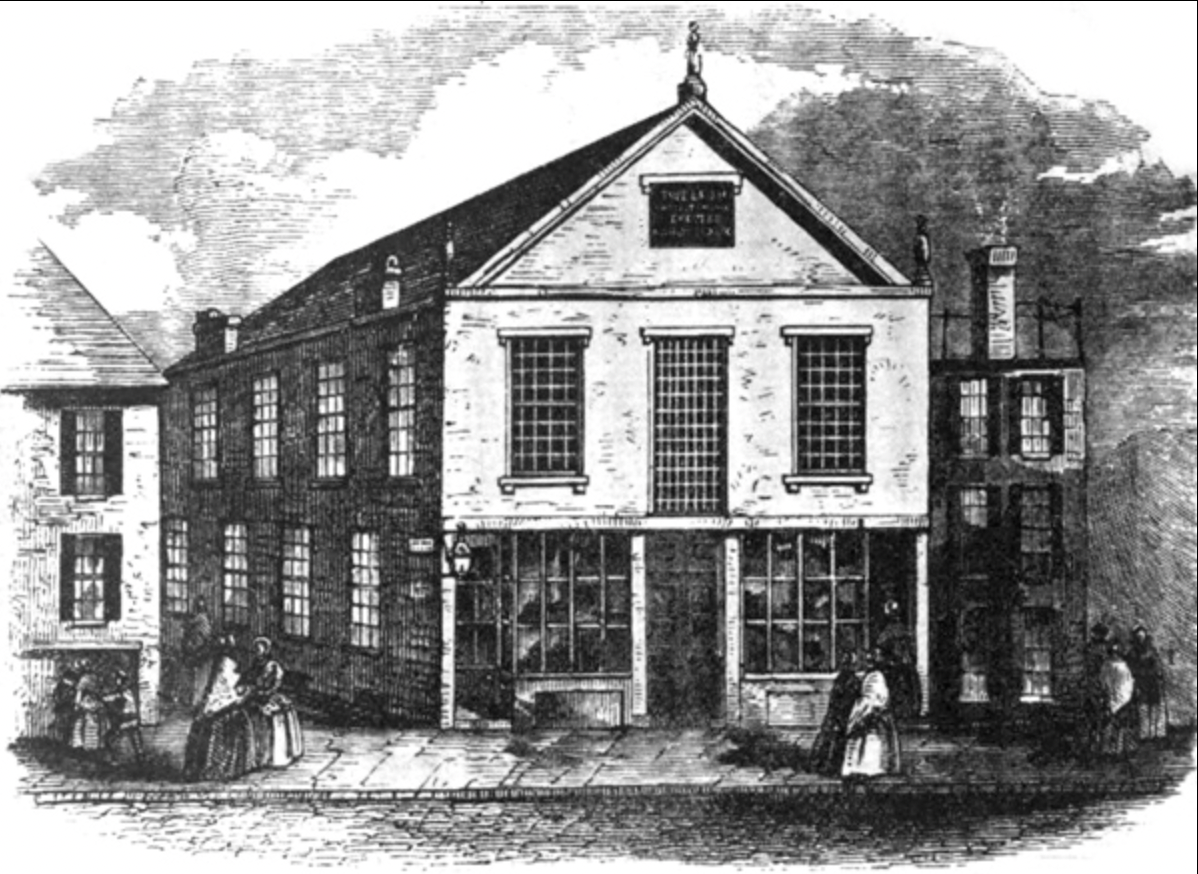

In late 1839, Leonard Grimes, an African American hack driver, drove 30 miles into Loudoun County, Virginia and rescued Patty, an enslaved woman along with her six children. His success was short-lived. Arrested in Washington, DC three months later, Grimes was hurried off to Richmond to stand trial. By early 1840 Grimes had been sentenced to two years at hard labor in the penitentiary in Richmond and fined $100. Soon after his release, he and his family moved to Boston, where he became the first pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church, which became known as both The Fugitives Church and the Abolition Church. There Grimes continued his abolitionist work and open defiance of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. For helping hundreds of freedom seekers make their way to Canada, Grimes has been characterized as one of the most successful agents of the Underground Railroad.

Twelfth Baptist Church of Boston as it appeared in the 1850s (Wikipedia)

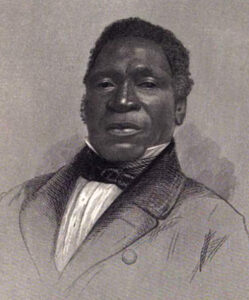

AME minister Josiah Henson (Library of Congress)

Josiah Henson, another effective Underground Railroad figure, preached his way across Ohio, earning money enough to purchase his freedom from the slaveholder in Maryland. After the slaveholder cheated him out of those funds, Henson finally decided to escape slavery with his wife and four children in Kentucky. Following his remarkable yet arduous journey to Canada, Henson went on to national and international fame as an AME minister, an abolitionist, and organizer of Canada’s Dawn settlement. Henson’s conversion at 19 years old shows how religion—particularly Methodism–sowed the seeds of liberation through realization of Christ’s love, one’s divine nature and purpose, access to salvation, individual redemption, and life everlasting beyond worldly suffering. Henson considered his contributions on the Underground Railroad the outstanding achievement of his illustrious career..[5]

White ministers also risked their lives and freedom working for the Underground Railroad. Twice arrested and jailed Methodist minister Calvin Fairbank stands out among this class of men. His rescue of the Lewis Hayden family was a major act of Underground Railroad activism and an outstanding contribution to the free Black community of Boston. Lewis Hayden and his wife Harriet became premier Underground Railroad workers in Boston. The people of God had to choose –answer the higher call of conscience to aid freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad or obey the unjust laws of the land. Congregations, churches, and ministers provided refuge and safe haven for freedom seekers and a moral compass for the nation.

Lewis and Harriet Hayden (pictured above) were aided in their escape from Kentucky by Methodist minister Calvin Fairbank and schoolteacher Delia Webster (NPS)

Working between interracial cooperation and across racial fault lines, different denominations shaped the Underground Railroad and the antislavery movement. White churches and ministers actively upheld both pro- and antislavery positions. Just as slavery gnawed at the soul of the nation, it tore white denominations into northern and southern factions. In 1844, Southern Methodists interested in upholding the practice of slavery split from the mother church. Southern Baptists followed suit in 1845 when they split from the larger Baptist denomination over slavery.

Just as slavery gnawed at the soul of the nation, it tore white denominations into northern and southern factions.

Work on the Underground Railroad brought a solidarity of purpose to pre-Civil War Black churches across denominations and regions. The Black church functioned as the center of civic engagement and the cradle of uplift in the Black community. When it came to slavery and the Underground Railroad, justice was never guaranteed. Frederick Douglass observed that the country supported slavery in “custom, manners, moral and religion.” The government and the rule of law struck “the blow for a firmer hold and a longer lease of oppression.”[6] It took the suspected yet clandestine power of the independent Black church, its ministers, and congregations to help defeat slavery and oppression through the illegal yet righteous work of the Underground Railroad.

Further Reading

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. New York: Amistad / HarperCollins, 2005.

- Franklin, John Hope and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Grendler, Marcella, Andrew Leiter, and Jill Sexton, compilers. North American Slave Narratives. Guide to Religious Content in Slave Narratives, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/religiouscontent.html accessed March 31, 2021.

- LaRoche, Cheryl Janifer. Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance. Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 2014.

- Mitchell, William. The Underground Railroad: From Slavery to Freedom. London: William Tweedie, 1860.

- Benjamin Quarles, Black Abolitionists. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

- Ripley, C. Peter, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Vol. III & IV. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Discussion Questions

- Have you thought of African American churches as Underground Railroad sites before?

Citations

[1] Samuel Ringgold Ward, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-slavery Labours in the United States, Canada & England (London: John Snow, 1855), 64, 65, 66. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wards/ward.html

[2] AMEZ ministers Christopher Rush, Jehiel Beman and his son, Amos Beman who served as assistant secretary, Colored Presbyterian ministers Theodore Wright , who offered the closing prayer, Samuel Cornish, Henry Highland Garnett, Andrew Harris (died in 1841), Stephen Glouster and J. W. C. Pennington (also Congregationalist), Congregationalist Charles B. Ray. See American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists: Conscience of the Nation, American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (AFASS) http://www.americanabolitionists.com/american-and-foreign-anti-slavery-society.html#Officers and Black Abolitionist Papers, V. III, p. 23.

[3] Sarah J. Early, Life and Labors of Reverend Jordan W. Early: One of the Pioneers of African Methodism in the West and the South (Nashville: Publishing House of the A.M.E. Church Sunday School Union, 1894), p. 37.

[4] Philanthropist, October 28, 1836

[5] Josiah Henson, Uncle Tom’s Story of His Life (Boston: B.B. Russel, 1879).

[6] Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction,” Atlantic Monthly 18 (1866): 761-765.

Author Profile

CHERYL JANIFER LAROCHE is an associate research professor at the University of Maryland who combines law, history, oral history, archaeology, geography, and material culture to define nineteenth century African American cultural landscapes and its relationship to the escape from slavery. She holds a PhD in American Studies with a concentration in Archaeology and African American history from the University of Maryland, College Park. She is the author of Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (University of Illinois Press, 2014), which explores the landscapes of Black communities and their relationship to the Underground Railroad. She has consulted for Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, several National Park Service sites, the African Burial Ground Project and numerous museums, cultural institutions and historic sites.

CHERYL JANIFER LAROCHE is an associate research professor at the University of Maryland who combines law, history, oral history, archaeology, geography, and material culture to define nineteenth century African American cultural landscapes and its relationship to the escape from slavery. She holds a PhD in American Studies with a concentration in Archaeology and African American history from the University of Maryland, College Park. She is the author of Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (University of Illinois Press, 2014), which explores the landscapes of Black communities and their relationship to the Underground Railroad. She has consulted for Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, several National Park Service sites, the African Burial Ground Project and numerous museums, cultural institutions and historic sites.

Related Works and Appearances by Cheryl Janifer LaRoche

- Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad (GBH, 2014)

- Tales from the Underground Railroad (TedxTalks, 2016)