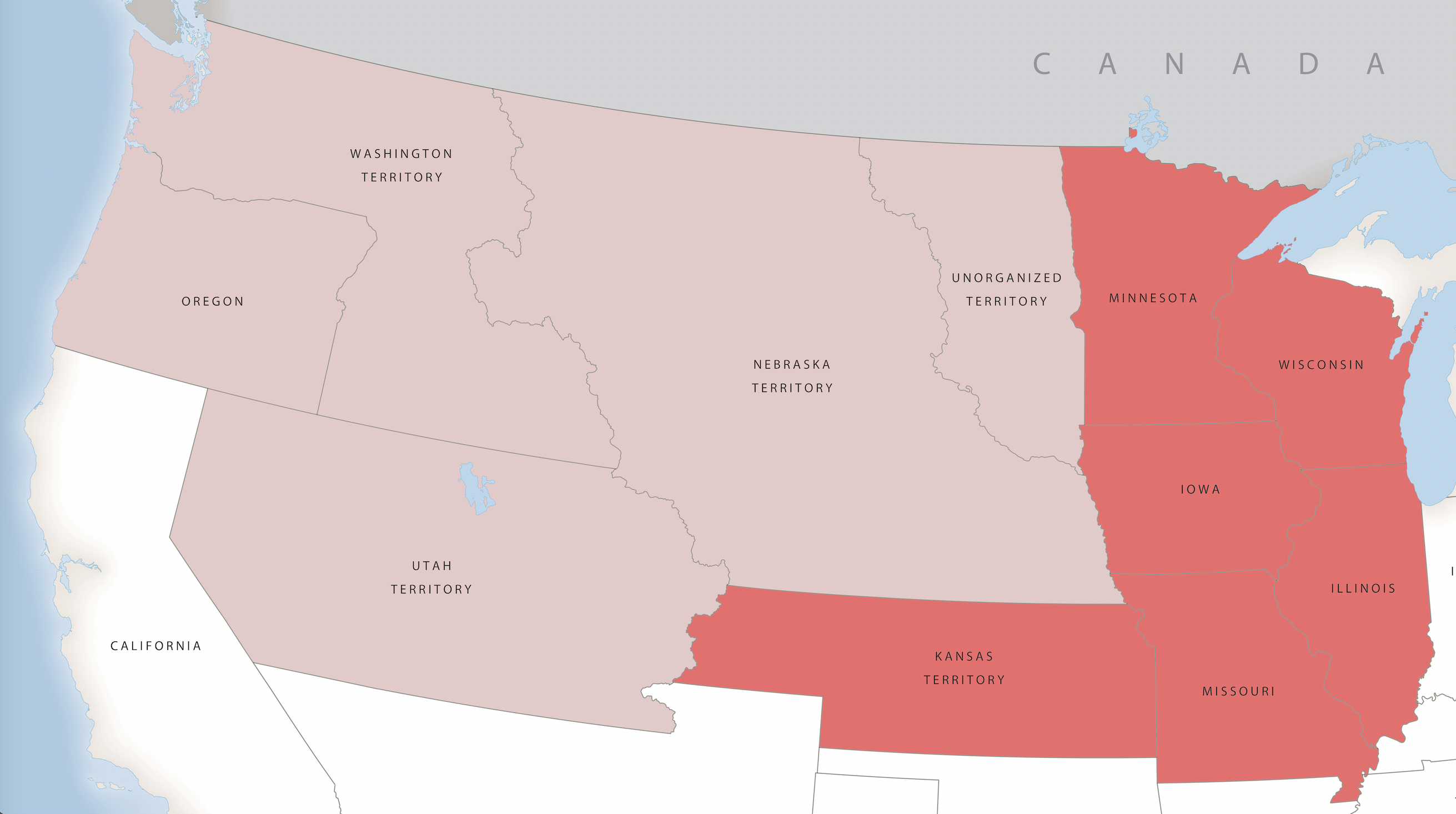

Banner image: In January 1859, slave catchers ambushed abolitionist Dr. John Doy and a “stampede” of Missouri freedom seekers inside the Kansas territory. (Le Tour du Monde, 1862, colorized by Amanda Donoghue, House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay

- See related Timeline entries

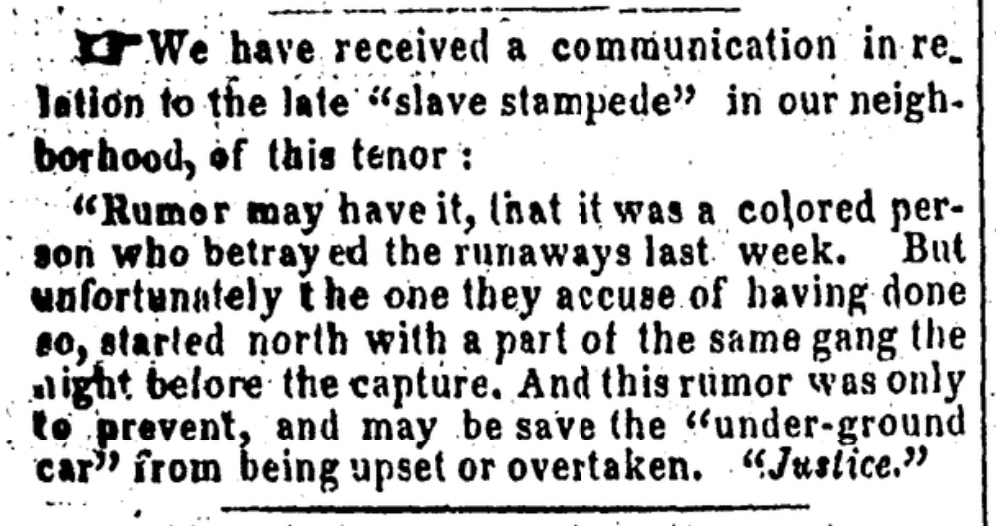

In January 1850, about a dozen freedom seekers escaped from St. Louis, Missouri and made their way through Illinois.[1] Newspapers labeled this act of cooperative self-determination as a “slave stampede.” The terms “slave stampede,” “stampede of slaves,” “negro stampede,” “black stampede,” “African stampede,” “stampede of Africans” were used starting in the late 1840s, to talk about enslaved people escaping in groups or by several escapes from the same location in a particular space of time. The appearance of the term coincided with the growing perception that slavery was seemingly under threat. These escapes were tantamount to small insurrections, challenging not only the authority of the enslavers, but also the very legitimacy of the slave system.[2]

This report of a “slave stampede” from St. Louis appeared in Abraham Lincoln’s hometown newspaper in 1850 (Springfield IL Daily Journal, January 22, 1850)

Stampedes were largely a borderlands phenomenon. As the term suggests, the stampedes metaphor had its origins in the western experience. The Underground Railroad on the northwestern frontier thus cannot be disconnected from the larger history of westward expansion and the growing conflict over the extension of slavery. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in areas north of the Ohio River, paving the way for Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin to all be admitted as “free states.” These states would be followed by establishment of other free territories and states even further west, such as Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, and Nebraska. Their locations provided unique prospects for escape and flight. As a result of the 1820 compromise, Missouri entered into the Union as a slave state with the longest border adjacent to free states and territories: Illinois, Iowa and (later) Kansas. The 1850 slave stampede was just one of the many escapes along these Missouri borderlands.

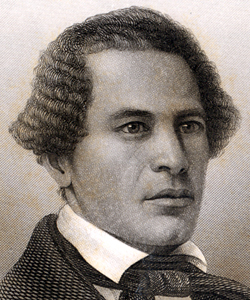

William Wells Brown (House Divided Project)

The many waterways that flowed through the region, including the Mississippi, the Missouri and the Detroit rivers and the Great Lakes, were also integral to the Underground Railroad. It was while being hired out on a steamboat that William Wells Brown, an enslaved man from Missouri, started to long for freedom. He wrote, “the situation was a pleasant one to me;–but in passing from place to place, and seeing new faces every day, and knowing that they could go where they pleased, I soon became unhappy, and several times thought of leaving the boat at some landing place, and trying to make my escape to Canada, which I had heard much about as a place where the slave might live, be free, and be protected.”[3] Yet despite his desire to be free, Brown at first refused to escape, unwilling to leave behind his enslaved mother.

As Brown’s own experience illustrates, many of the crews of vessels that plied these waterways included African Americans, both enslaved and free, who provided assistance to freedom seekers. In fact, it was common knowledge that while traveling up the river through slave states, these workers were often confined in local jails while onshore to prevent them from facilitating escapes.

In an early attempt to neutralize waterways as an avenue to freedom, Missouri had passed a law in 1804 making it illegal for boats to transport enslaved people without the permission of their enslavers. Despite the prohibition, Caroline Quarlls, an enslaved teenager in St. Louis, was able to escape aboard a water vessel in 1843. Quarlls who was light-skinned, posed as white and purchased passage on an Illinois-bound steamboat. She made her way along the Underground Railroad traveling through Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan where she crossed from Detroit into Sandwich, Ontario (now Windsor).

Birds-eye view depicting the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers at Cairo, Illinois (House Divided Project)

Underground Railroad activity in the region did not solely rest with its geography. The region was an important site for migration and settlement for those opposed to slavery. In Iowa, communities of various religious denominations, including Quakers, Congregationalists, Methodist, and Presbyterians, all served as important allies along the Underground Railroad. It was not unusual for migrants to have previous Underground Railroad experience. Activity in Bond and Putnam Counties in Illinois was attributed to the migration of people from Brown County, Ohio, an important stop along the Underground Railroad.

Underground Railroad activity in the region did not solely rest with its geography. The region was an important site for migration and settlement for those opposed to slavery.

Among the region’s pioneers were people of African descent, who settled in both rural and urban areas. Amidst their own struggles for freedom and equality, they were not just content to secure their own freedom. For those who were born free or had achieved their freedom through legal or extralegal means, they realized that as long as the majority of people of African descent were held in bondage their own freedom was threatened. They actively assisted others in reaching destinations (usually further north) or welcoming them into their communities. An antislavery newspaper had the following to say about the African American community in Detroit: “One thing by the way is certainly credible to the public spirit and humanity of the colored people of our city…they always display a commendable zeal and harmony of action when their aid is needed to secure the safety of some poor fugitive brother escaping from the land of blood.”[4] In the 1850 slave stampede from St. Louis, it was Jameson Jenkins, a free African American drayman originally from North Carolina and a neighbor of future president Abraham Lincoln, who provided the initial assistance to the group in Springfield, Illinois.

Native Americans in the region also played a role in the Underground Railroad. Not only were some of them freedom seekers who escaped enslavement, but also, they helped others escape. Tribes that migrated to the region were important to the operations of the Underground Railroad. In Wisconsin, the Stockbridge and Brothertown Indians, tribes that had migrated to the state from New England, were leading Underground Railroad activists. The migration of Wyandot and Shawnee Indians also proved essential to the work of the Underground Railroad.

The illegality of slavery in the region did not mean it was free from racism and discrimination, as evidenced by the Black laws that sought to restrict and discourage African American migration and settlement into states formed out of the Northwest Territory. The laws limited the economic, political, and civil rights of free Blacks in several places. In addition, the persistence of de facto slavery, despite its illegality, also added complexity to the Underground Railroad in the region.

Slavery had a long history in the northwestern region, a vestige of the region’s colonial and territorial past, begun when the area was primarily under French control.

Slavery had a long history in the northwestern region, a vestige of the region’s colonial and territorial past, begun when the area was primarily under French control. The French practiced the enslavement of both Native Americans and people of African descent. Even when the United States came to power in the Mississippi and Ohio valleys, enslaved people continued to be sold, bought, transferred, and inherited. Many state constitutions narrowly prohibited slavery but left loopholes for the continuation of these practices. While the long border with slave states enabled escapes on the Underground Railroad, it also allowed for strong relationships between the economies of the western free and slave states. The southern portions of northwestern frontier states like Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin were invested in the slave economy, even renting enslaved labor, especially to work in the salt and lead mining industries. The first case to be heard by the Iowa Territorial Supreme Court, In the Matter of Ralph, (a colored man,) on Habeas Corpus (1839) declared that “no man in this territory can be reduced to slavery.” This case revolved around an enslaved man named Ralph Montgomery whose enslaver had agreed to let him work in the Dubuque mines to earn money for the purchase of his freedom but then Ralph was captured as a fugitive slave.[5] Enslavement also continued at military installations such as at Fort Snelling in the Minnesota territory, the existence of which would take center stage during the infamous Dred Scott case (1857).

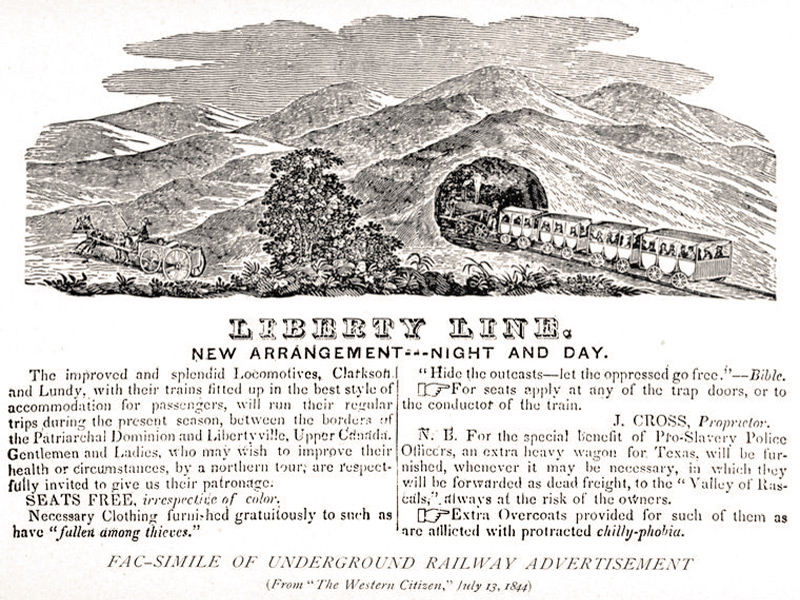

Slavery also persisted in the states carved out of the Northwest Territory in the form of coercive indentured contracts, which enabled enslavers to migrate into the territory with their enslaved “property” and continue holding them in bondage. Such was the case of Susan Borders. Andrew Borders, an enslaver from Georgia had migrated to Randolph County, Illinois in 1816, with his family and four enslaved people with him, including Susan who was still a child at the time. In Illinois, he held Susan, and her three sons under indenture contracts. Andrew Borders also held others under indenture including a young woman named Hannah Morrison and her mother. However, in 1842, Susan and her children, and Hannah would escape, using Illinois’s established Underground Railroad networks, eventually making their way to Knox County, a known abolitionist stronghold. There they were captured, and several legal battles ensued. While Susan and Hannah were able to secure their freedom, Susan’s children were returned to involuntary servitude. Among those tried for providing assistance to the freedom seekers was Rev. John Cross, a member of Theodore Weld’s Seventy, a group of public speakers formed under the auspices of the American Anti-Slavery Society to spread abolitionist ideas across the country. Cross used his travels as an antislavery lecturer and itinerant preacher to set up Underground Railroad routes in Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Iowa. Battle Creek, Michigan operative Erastus Hussey would later attribute his own involvement in the Underground Railroad to Cross.

1844 illustration from a Chicago abolitionist newspaper, touting the “Liberty Line,” and listing “J. Cross” as proprietor (NYPL)

Despite the hostilities and the persistence of slavery in the region, the Underground Railroad continued to develop. While in many places the Underground Railroad was loosely organized and often spontaneous, as it expanded westward to include Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas, it became increasingly deliberate, especially after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. The law had outraged many abolitionists and what had heretofore been largely a social and moral issue became increasingly politicized. In defiance of the new law, and despite the potential repercussions, Underground Railroad activity increased. An 1852 article pointing to the law’s failures and inadequacies read: “The stampedes of slaves from the border States afford a bad commentary on the practical workings of the measures of Adjustment.”[6]

Tensions were further inflamed with the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act which allowed popular sovereignty to decide whether slavery would be legalized in the Kansas and Nebraska territories. This prompted a wave of both pro- and antislavery migration into the region, resulting in violent clashes, especially in Kansas, that in many ways anticipated the Civil War. During the struggle to establish Kansas as a free state, John Brown, later of Harpers Ferry notoriety, entered into the national consciousness. The havoc he wreaked on proslavery forces included Underground Railroad activity. According to one report, “The effect of Old Brown’s movement has been to thin out the slaves along the border counties quite rapidly. Many who hear the news take courage and run away, the depots of the Underground Railroad in Kansas being full to overflowing; and masters taking the alarm are hurrying their slaves off to a Southern market as fast as possible.”[7]

The Underground Railroad continued in the region after 1861 as enslaved people “understood the war to be for their freedom.”[8] Despite reports that slavery was no longer profitable in wartime Missouri and was disappearing from the state, there was still a strong investment in the system and enslavers continued to pursue freedom seekers. When Henry Clay Bruce escaped from Missouri to Kansas with Pauline, his fiancée, in 1864, slave catchers followed in pursuit. The couple traveled by foot and train, eventually crossing the Missouri River by ferry to Leavenworth, Kansas. It was only after arriving there that Bruce “felt myself a free man.”[9] It was not quite a slave stampede, but like so many others before him in this borderlands region, Bruce had somehow found a way to emancipate himself and those he loved.

Further Reading

- Cox, Anna-Lisa. The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality. New York: Public Affairs, 2018.

- Epps, Kristen. Slavery on the Periphery: The Kansas-Missouri Border in the Antebellum and Civil War Eras. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016.

- Heerman, M. Scott. The Alchemy of Slavery: Human Bondage and Emancipation in the Illinois Country, 1730-1865. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

- La Roche, Cheryl. Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

- Smardz Frost, Karolyn and Veta Smith Tucker, eds. A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance, and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland. Detroit, MI: Wayne State Press, 2016.

- Soike, Lowell J. Necessary Courage: Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle Against Slavery. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2013.

Citations

[1] Illinois State Register, January 17, 1850; Illinois State Journal, January 22, 1850; Illinois State Journal, January 23, 1850.

[2] Currently, the National Park Service is conducting the project, “Slave Stampedes on the Southern Borderlands,” in partnership with Dickinson College, an effort looking at slave stampedes, focusing on the Kentucky and Missouri Borderlands. It is being funded by the National Park Service’s Civil Rights Commemoration Initiative Funding. The initiative supports projects relevant to African American civil rights and experiences, including slavery, resistance, Reconstruction, and the American Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century and beyond. For more on the project, visit: https://stampedes.dickinson.edu.

[3] William W. Brown, Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave. Written by Himself (Boston: The Anti-Slavery Office, 1847), 31.

[4] “Detroit Affairs,” Signal of Liberty, April 6, 1846.

[5] William J. A. Bradford, Reports of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of Iowa, from the Organization of the Territory in July, 1838, to December, 1839 (New York: Polygraphic, 1840), 6.

[6] “Letter from Washington,” The Democrat, December 24, 1852. The term measures of adjustment refers to the Compromise of 1850, of which the Fugitive Slave Act was part.

[7] Cleveland Daily Leader, January 25, 1859.

[8] H. C. Bruce, The New Man: Twenty-Nine Years a Slave. Twenty-Nine Years a Free Man (York, PA: F. Antstad & Sons, 1895), 99.

[9] Bruce, The New Man, 109.

Author Profile

DÉANDA JOHNSON is currently the Civil Rights Historian with the National Park Service, Interior Region 2. She previously served as Midwest Regional Coordinator for the National Park Service Network to Freedom Program in Omaha, Nebraska. In that capacity, she worked with local, state, and federal entities, as well as other interested parties to preserve, promote, and educate the public about the history of the Underground Railroad. Previously, Johnson was the Coordinator of the African American Research and Service Institute at Ohio University and she also served as a visiting instructor in the Department of African American Studies. She received her BA from University of California, San Diego and her MA and PhD in American Studies from the College of William & Mary.

DÉANDA JOHNSON is currently the Civil Rights Historian with the National Park Service, Interior Region 2. She previously served as Midwest Regional Coordinator for the National Park Service Network to Freedom Program in Omaha, Nebraska. In that capacity, she worked with local, state, and federal entities, as well as other interested parties to preserve, promote, and educate the public about the history of the Underground Railroad. Previously, Johnson was the Coordinator of the African American Research and Service Institute at Ohio University and she also served as a visiting instructor in the Department of African American Studies. She received her BA from University of California, San Diego and her MA and PhD in American Studies from the College of William & Mary.