Banner image: Fearless women such as Mary Elizabeth Grigsby made the Underground Railroad a reality. Grigsby helped spearhead a successful resistance effort on Christmas Day 1855 between a half dozen Virginia freedom seekers and a posse of slave catchers. She later settled in Canada with her husband and her sister Emily and her husband –all of whom had escaped together. Original illustration depicting the Christmas Day confrontation by Charles H. Reed from William Still’s Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Charlotte Goodman (House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

In early May 1856, a 22-year-old enslaved woman named Winnie Patsy boarded a vessel in Norfolk, Virginia, with her three-year-old daughter Elizabeth. Hidden securely onboard by the antislavery captain, the mother and child sailed to Wilmington, Delaware, where Quaker stationmaster Thomas Garrett procured their passage for the last few miles to Philadelphia and freedom.

Winnie and Elizabeth safely reached the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (PASS) office of Philadelphia’s preeminent Black abolitionist and Underground Railroad leader, William Still, who was awaiting their appearance after Garrett alerted him by letter of their imminent arrival. On May 16, Still documented their names and a few details of their journey in his now-famous record of freedom seekers called Journal C, before forwarding them by train to stationmaster Sydney Howard Gay in New York City. By the time Gay met them in New York, Winnie had been seven months on the run. She and her toddler were lucky to have survived.

Still and Gay noted that Winnie’s husband, who had fled his Norfolk enslaver in the early fall of 1855, arranged for the ship captain to bring his wife and their daughter north as soon as they could get away. That proved more difficult than the small family imagined. Winnie’s enslaver, she later reported, was a “tyrant,” who suspected she would flee, so he tried to sell her. By mid-October, the ship captain had not yet returned to Norfolk, and Winnie knew that her dream of freedom was growing dimmer each day.

Desperate, Winnie placed her trust in an underground network in the region. She escaped with Elizabeth to the cabin of a bondsman who regularly sheltered freedom seekers. He had carved a small “cave” beneath his house, accessible through a hidden trap door in the floor of the cabin. The hiding place “had no window, & no means of light or ventilation,” Winnie later told her liberators. She and Elizabeth hid there for months and “[s]uffered extremely from the dampness & cold,” especially during winter’s freezing temperatures. A society “among the slaves, organized to aid persons” escaping from slavery, provided them with food. Eventually, the ship captain returned to Norfolk and secretly sailed them to freedom.[1]

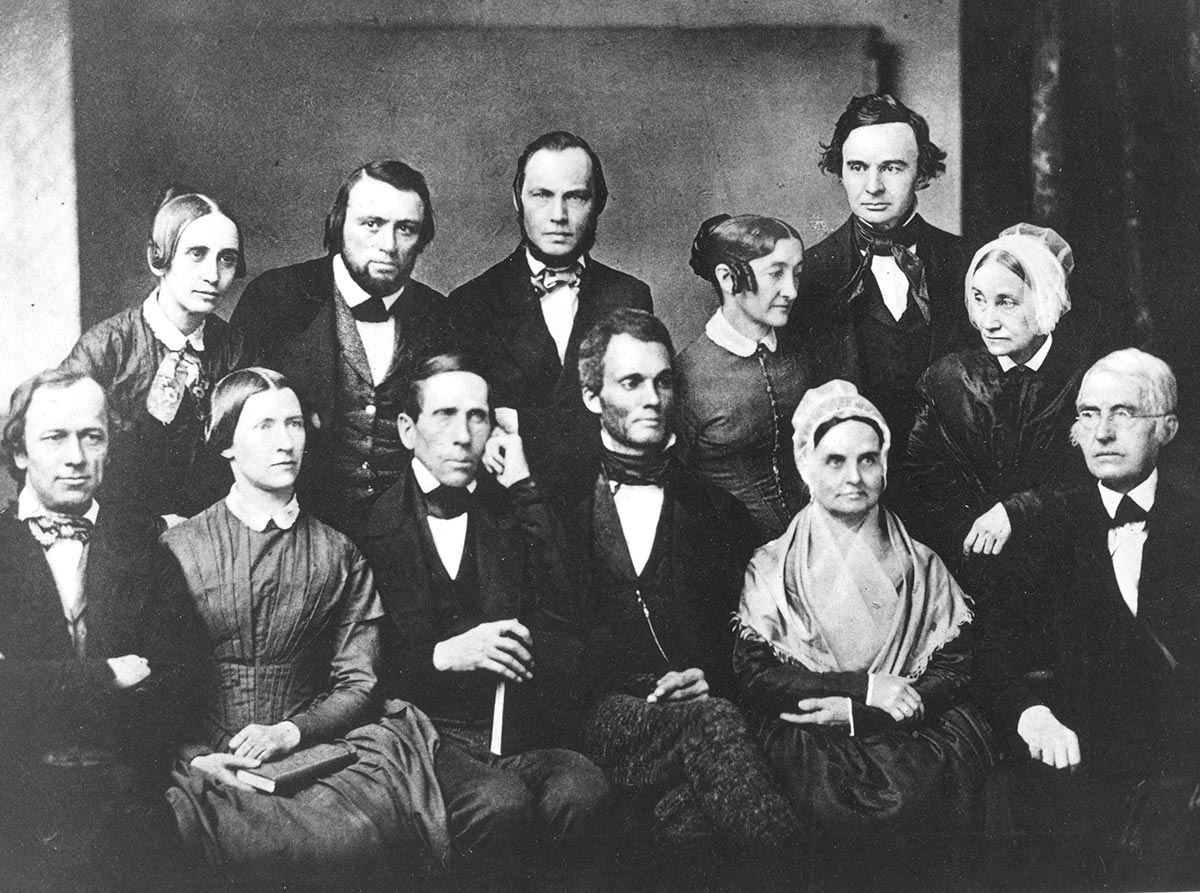

During the 1850s, Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society executive members included both men and women (Swarthmore College)

Only about 240 out of the nearly 1,000 self-liberators whom William Still documented in his account books between 1853 and 1861 were females. The gender disparity is glaring but not surprising. Historians John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger found similar percentages. Nearly 80 percent of freedom seekers in their study of escapes from Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Louisiana, were men and boys.

A closer look at the figures reveals that 74 percent of the males in the Franklin and Schweninger study were teenagers and young men in their 20s, while young women in the same age group represented 68 percent of women who escaped. William Still’s records of formerly enslaved people who reached his office show a slightly different demographic: 56 percent of the males he documented were in that same age range. Girls and young women in their teens and early twenties constituted 64 percent—or 154—of all of Still’s female freedom seekers.

Harriet Tubman in her mid-40s (NPS)

Childless women and women separated from their children through sale or renting out by their enslavers dominated the numbers. Winnie, and other women like her who escaped with their children, were relatively rare. The risks associated with escaping with young children were much higher and served as a serious impediment to flight. Harriet Tubman, one of the most famous Underground Railroad conductors of the antebellum period, struggled for nearly a decade to bring her sister Rachel Ross and Rachel’s two children, Ben and Angerine, to freedom from Dorchester County, Maryland. Tubman, who had no children of her own when she successfully escaped enslavement by the Brodess family in the fall of 1849, returned repeatedly to the Eastern Shore of Maryland to escort nearly 70 family members and friends to free states and Canada. After Tubman helped her 19-year-old brother Moses Ross escape in 1851, and three more brothers on Christmas Day in 1854, the Brodesses suspected Rachel might flee too. To control her, they separated her from her children by leasing them to other farmers. They rightly calculated that Rachel would not abandon them; she told Tubman that she would not escape without her children. Despite Tubman’s repeated attempts to rescue them together throughout the 1850s, Rachel remained enslaved. In 1859, she died and Angerine and Ben stayed trapped in slavery. Tubman could not help them.

Women choosing to leave their children behind in slavery faced an impossibly difficult decision that kept most from fleeing.

Charity (Sydney) Still, illustration from her son William Still’s, Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Jordan Schucker (House Divided Project)

Women choosing to leave their children behind in slavery faced an impossibly difficult decision that kept most from fleeing. Some women navigated that decision with heartbreaking consequences. William Still’s mother, Sydney, was forced to make such a choice. She and her husband Levin were enslaved by different men in Caroline County, Maryland. Levin’s enslaver, William Wood, manumitted him in 1798, while Sydney and their children remained the property of Alexander “Saunders” Griffith. Levin moved to central New Jersey, then a free state, sometime around 1806, leaving Sydney to execute a risky escape with their four young children—Peter, Levin Jr., Mahala, and Kitty. Her attempt to reach Levin failed when slave catchers captured her near Greenwich, New Jersey. After locking her in the attic of his brick home for three months as punishment, Griffith let Sydney out. She fled again. This time, however, she took only her two daughters and left Peter and Levin Jr. behind. In retaliation, Griffith sold the boys to Kentucky, hoping to ensure they would never see their mother again. For Sydney, her desperate decision to claim freedom for herself and daughters came at an extraordinary price.

Levin and Sydney, who changed her name to Charity, established a free home in Burlington County, New Jersey, where they had fourteen more children, including William, their last, in 1821. William grew up hearing his parents’ tragic story of freedom that cost them so much. The fates of the boys remained a painful mystery to the Still family. That pain deeply informed William’s decision to work for the PASS as secretary of the vigilance committee which helped freedom seekers arriving in Philadelphia.

In the intervening years, Levin Jr. died after being sold from Kentucky to Alabama. Peter survived and escaped in 1850 and found his way to Philadelphia, where he met William in the vigilance committee offices. As William questioned Peter about his life, he realized that Peter was his long-lost brother. Their chance encounter resulted in the reunification of Peter with the Still family in New Jersey, including his mother Charity who was still alive. The improbable reunion convinced William to formally document the names and stories of freedom seekers coming through the society’s office so that separated family members might eventually find each other.[2]

Women freedom seekers often encountered female agents of the Underground Railroad wherever they went. Work by women in the network to freedom often remains hidden behind the more famous men whose access to the public sphere ensured better documentation and acknowledgment of their efforts. Women of all backgrounds participated, including free and enslaved Black women, white women, and Native American women. They carried on the subterfuge as successfully as men in the movement networks. As managers of the domestic sphere, they offered shelter, food, clothing, medicine, transportation, and, on occasion, they used weapons to protect their guests.

Women of all backgrounds participated, including free and enslaved Black women, white women, and Native American women.

Records reveal a broad demographic of women participants. Leading suffragist and abolitionist Quaker Lucretia Coffin Mott worked with William Still and numerous men in support of the Middle Atlantic Underground Railroad networks. Harriet Tubman remembered Mott as the first white woman who helped her in Philadelphia. According to Underground Railroad agent Robert Purvis, Black and white female market vendors who sold produce and other goods on waterfronts and in busy commercial districts discreetly delivered forged documents and passed information to freedom seekers and their allies in Baltimore.[3] William Still sent self-liberators to Sarah Buchanon, a free Black boarding house operator in Philadelphia, who hid them among the Black watermen and dock workers who lodged in her home.

Thomas Garrett helped approximately 2,700 freedom seekers during a 40-year career of antislavery activism. He ran a business selling metals in Wilmington, Delaware, which consumed much of his daytime activities. His success as an Underground Railroad agent, however, was dependent upon the work of his wife Rachel, who cared for the self-liberators who found their way to the Garrett home. Quaker businessman Levi Coffin and his wife Catherine operated busy underground stations in Indiana and Ohio, sheltering and transporting a reported 3,000 freedom seekers. Despite their shared responsibilities, only he bears the honorific nickname “President of the Underground Railroad.”

Mary Meachum and her husband John purchased their freedom in the 1810s from their Missouri enslavers and established a home and school in St. Louis. For decades they helped self-emancipators navigate their race to freedom, and they also purchased twenty enslaved people with money they saved working various jobs in the city and then set them free. In May 1855, just over a year following her husband’s death, Mary was implicated in a failed escape attempt. Authorities caught a group of nine freedom seekers escaping across the Mississippi River to Illinois, a free state. Meachum faced charges of committing a crime, when one of the captured men identified her home as their rendezvous point. But these charges were soon drooped and Meachum resumed her antislavery work.

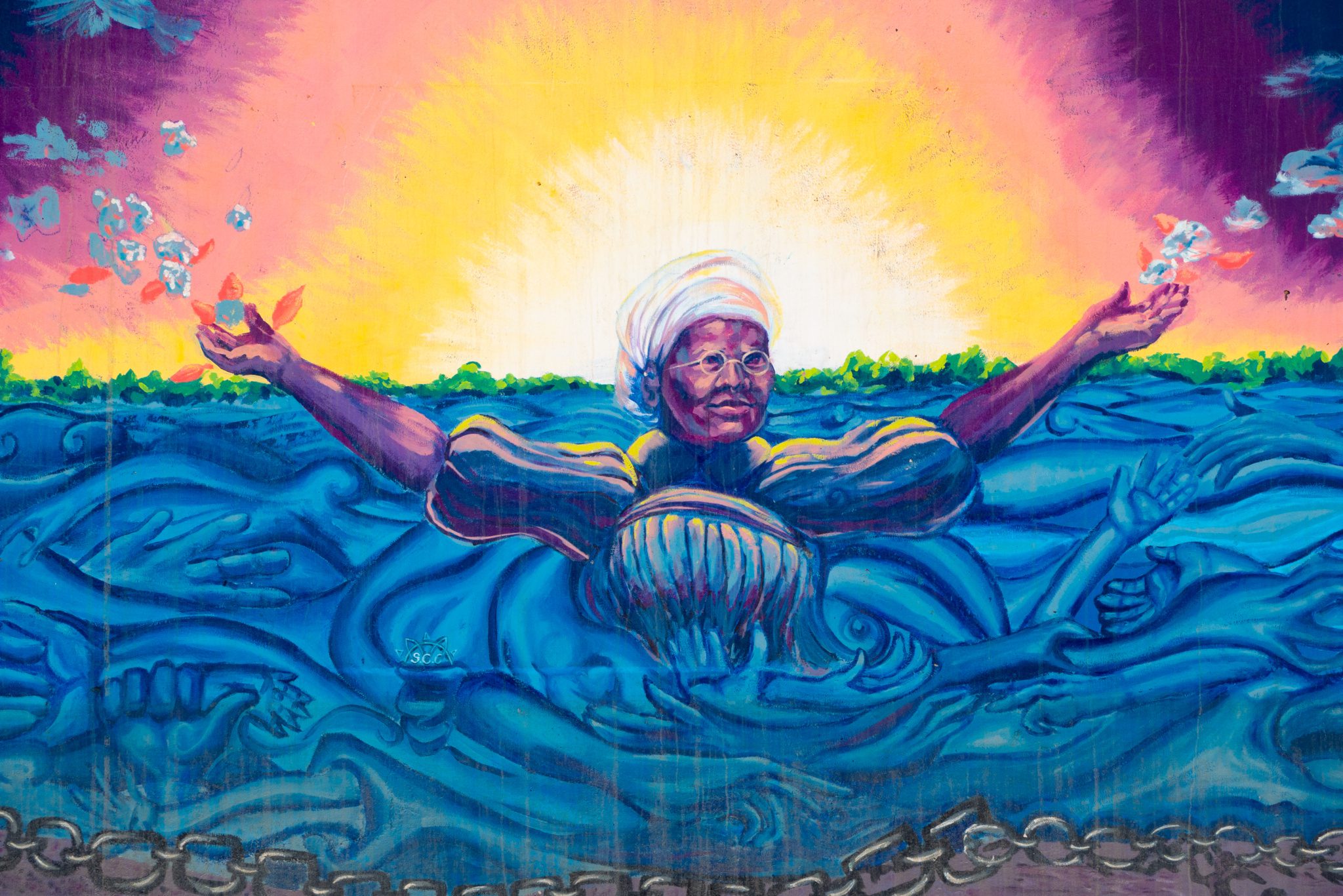

The Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing in St. Louis commemorates her role in an attempted “slave stampede” from the city in 1855 (Great Rivers Greenway)

Frederick Douglass’s home in Rochester, New York was a busy Underground Railroad station. Its success as one of the last depots on the network to freedom route through central New York to the Canadian border is attributable to his wife, Anna Murray. Douglass was frequently away from home, leaving the work of managing the security and wellbeing of their temporary guests in Murray’s hands. Harriet Hayden, the wife of Black abolitionist Lewis Hayden served in the same capacity in the Hayden home in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. Considered operators of the main underground station in Boston, the Haydens assisted hundreds of freedom seekers. Like Sarah Buchanon in Philadelphia, Harriet ran the Hayden home as a boarding house, sheltering freedom seekers among her paying lodgers.

Ellen and William Craft, a young couple who escaped together from Macon, Georgia in December 1848, were among those hosted by the Haydens. Ellen’s daring plan to pass herself off as a white man traveling with William as her enslaved servant ranks as one of the Underground Railroad’s most ingenious escapes. The daughter of her enslaver, Ellen’s light complexion and her intimate knowledge of white behavior gleaned through her years as a house servant enabled the couple to execute the plan. Disguised as a young man suffering from poor health, Ellen successfully deflected any suspicions about who she was and where she was going with William. They brazenly traveled aboard trains and sailing vessels, finally reaching Philadelphia on Christmas Day and then, a few days later arriving in Boston where the Haydens helped them settle.

Anna Maria Weems escaped Washington in 1855 disguised as a male chauffeur (1872, illustration, colorized by Forbes, House Divided Project)

Ellen Craft was not the only enslaved woman disguising herself as a man to facilitate an escape. Fifteen-year-old Anna Maria Weems dressed as a chauffeur and drove a carriage out of Washington, DC with abolitionist Dr. Ellwood Harvey. Harriet Tubman’s skills at such deception thwarted catastrophe several times along the way to freedom, as she disguised herself frequently as an elderly woman or man. Tubman’s brother Ben Ross, Jr., once helped his enslaved fiancée, Jane Kane, escape by providing her with a suit of men’s clothing. No one recognized her when she boldly walked away from her enslaver’s plantation.

When the Haydens had successfully escaped from their own enslavement, they were able to bring Harriet’s five-year-old son, Joe, with them from Lexington, Kentucky in 1844. Reverend Calvin Fairbank and his co-conspirator, Delia Webster, were arrested for their role in helping the Haydens reach Canada. Charged and convicted for aiding and abetting the Hayden family, Webster successfully campaigned for a pardon from Kentucky’s governor, and soon resumed her underground activities. On several occasions, white vigilantes threatened her, to which she responded with threats of violent reprisals of her own. Laura S. Haviland, one of the most successful and prolific agents in the Midwest who also worked with Reverend Fairbank and with Levi and Catherine Coffin in Ohio, risked her life thwarting slave catchers. One enslaver offered a $3,000 bounty to have Haviland murdered. The price on her head did not deter her.

The identities and stories of most women participants in the various networks to freedom remain shrouded in anonymity, but none more so than enslaved and free women of color, and Native American women. Freedom seekers escaping from western Virginia and Kentucky followed trails established long since by Native Americans into northwest Ohio, Michigan, and Canada. Before forced removal to reservations further west in the 1830s and 1840s, Shawnee, Wyandot, Ottawa, and other Native women sheltered, fed, and nursed tired, hungry, and anxious self-liberators who arrived in their villages. Slave catchers lurked along these trails, too. Free Black communities were often the target of surveillance and mob violence, making the work of women agents risky and dangerous. In 1858, Harriet Tillison, a free Black woman living in Kent County, Maryland came under suspicion of helping people escape from the area. A petite woman, “dwarfish in appearance, scarcely weighing fifty pounds,” Tillison was beaten, stripped of her clothes, tarred and feathered. The authorities then threw her in jail despite their inability to link her to a specific escape.[4] Tillison bore the brunt of anger from local slaveholders who had become alarmed by the high numbers of escapes from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. By the late 1850s, Harriet Tubman’s successful rescue missions were inspiring several large groups of men, women, and children to escape from the region, unsettling the imaginary tranquility which slaveholders claimed they had achieved with their bondspeople.

We can only fully appreciate the richness of the history of the Underground Railroad through teasing out such stories from long-silenced voices. Through more purposeful interpretation, the lives of the women of the Underground Railroad offer fresh opportunities to see beyond the famous men of the movement and recognize the equal and specific contributions and sacrifices women tendered in the pursuit of freedom.

Further Reading

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound For Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America. New York: Amistad / Harper Collins, 2005.

- Calarco, Tom. People of the Underground Railroad: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2008.

- DeRamus, Betty. Freedom by Any Means: True Stories of Cunning and Courage on the Underground Railroad. New York: Atria Books, 2009.

- Finkenbine, Roy E. “The Underground Railroad in ‘Indian Country’: Northwest Ohio, 1795-1843,” in Damian Allen Pargas, ed., Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018.

- Franklin, John Hope and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Kashatus, William C. William Still: The Underground Railroad and the Angel at Philadelphia. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021.

- Larson, Kate Clifford. Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003.

- Papson, Don and Tom Calarco. Secret Lives of the Underground Railroad in New York City. Sydney Howard Gay, Louis Napoleon, and the Record of Fugitives. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.

Citations

[1] See William Still, “Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia, Accounts,” and “Journal C of Station 2 of the Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, Agent William Still),” in Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers, (Philadelphia, PA: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1852–1857); and Still, The Underground Railroad (1871 rpt., Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, Inc., 1970.) See also, Sydney Howard Gay, “Record of Fugitives 1855 [–1856],” in Sydney Howard Gay Papers, 1743–1931, ed. Columbia University (Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 1855–1856). Winnie Patsy was also identified as Winnie Patty in some records.

[2] See Pat Guida, “Levin Still (1774-1842) and Charity Still (?-1857) in Caroline County, Maryland: Documenting the Still Family in the Public Records of Caroline County and the Province and State of Maryland. A Project for the William Still Interpretive Center.” Caroline County Historical Society, Denton, MD. 2019; and Kate E. R. Pickard, The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: The Narrative of Peter and Vina Still after Forty Years of Slavery (Syracuse: Miller, Norton and Mulligan, 1856; reprint Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1996). This narrative was dictated by Peter Still to Pickard in 1856. In his Underground Railroad memoir, William Still mistakenly identified his parents’ slaveholder as Saunders Griffin.

[3] R.C. Smedley, History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania (Lancaster, PA: John A. Hiestand, 1883). 355. Wilbur Henry Siebert, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Macmillan Co., 1898). 68.

[4] “Foul Outrage,” Liberator, Boston, MA, July 8, 1858.

Author Profile

KATE CLIFFORD LARSONis a historian and leading Harriet Tubman scholar who has taught at Simmons University in Boston, Massachusetts. After receiving undergraduate and master’s degrees from Simmons, she received her MBA at Northeastern and PhD at the University of New Hampshire. She is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal best-selling author who wrote multiple books including Bound For the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero(One World, 2003)andThe Assassin’s Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln(2008).Her work helped establish the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument which was approved by President Obama’s executive order.

KATE CLIFFORD LARSONis a historian and leading Harriet Tubman scholar who has taught at Simmons University in Boston, Massachusetts. After receiving undergraduate and master’s degrees from Simmons, she received her MBA at Northeastern and PhD at the University of New Hampshire. She is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal best-selling author who wrote multiple books including Bound For the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero(One World, 2003)andThe Assassin’s Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln(2008).Her work helped establish the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument which was approved by President Obama’s executive order.