Banner image: Freedom seekers confronted slave catchers inside a Maryland barn in October 1853 (From William Still’s Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Forbes, House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

John Anderson was an escaped slave who fled to Canada. On July 5, 1861, the Toronto Globe recounted the speech he gave before Canadian abolitionists. He did not reveal which slaveholding state he had escaped from, but for his audience it barely mattered. As he stood at the podium, the crowd began to cheer. Anderson was not used to public speaking and fed off their prolonged encouragement. He had only meant to say a few words about how he escaped. He claimed that to flee bondage, he had to cut and run and fight. “I don’t like to shed blood,” he acknowledged, but as he was fleeing, a pursuer was following his tracks relentlessly.

Historians do not know if the pursuer was his slaveholder or a slave catcher, but it was clear the person was set on capturing Anderson. Mile after mile, he could not shake his pursuer. He shouted at him to stay back and that if he kept up the chase, he would be forced to kill him. After two or three hours of pursuit, the man would not stop, so Anderson made good on his word. He killed him. As he was recounting this story, the audience held onto Anderson’s every word. To his surprise, once he confessed to murder, the audience erupted with cries of “You did right” and “Hear, hear!” Anderson lamented his actions, but contended that killing the man was a last resort and a necessary one if he were to gain his freedom. Again, the audience erupted with affirmation, shouting “Bravo!” and “You did right.” Anderson concluded by stating that he was a Christian man and hoped that after the murder he could still be considered a godly one. Once more, the crowd cheered and shouted: “It was a justifiable act.” As he finished, the reverend chairman of the meeting stood at the podium and proclaimed, “John Anderson did perfectly right… Does our fugitive friend look like a murderer?” The response of the audience was a resounding, “Hear, hear” and “No, no.”[1] These difficult stories of the Underground Railroad are often lost to history. Few choose to disclose or recount the violence that was endemic to fleeing the institution of slavery.

In the history of the movement to abolish slavery, scholars have given too little attention to the shift toward violence among Black abolitionists. But Black resistance, and in particular, violent resistance, was fundamental to emancipation. Black abolitionists had a profound understanding of the idea, experience, and value of violence. The endorsement of physical and political violence among Black abolitionists was a recycled strategy derived from four basic principles. First, fugitive slaves believed they were justified in using violence to protect their freedom just as American and Haitian revolutionaries had been in securing theirs. For Black abolitionists, the two great revolutions were more than a set of principles: they were precedents. In a letter published in Frederick Douglass’s newspaper the North Star, fugitive slaves declared, “If the American revolutionists had excuse for shedding but one drop of blood, then have the American slaves excuse for making blood to flow ‘even unto the horse-bridles.’”[2] To be clear, violence was not about vengeance for these activists, it was about securing rights and equal protection under the law.

In the history of the movement to abolish slavery, scholars have given too little attention to the shift toward violence among Black abolitionists. But Black resistance, and in particular, violent resistance, was fundamental to emancipation.

Second, black abolitionists justified what I have called protective violence. More than self-defense, protective violence was about the collective. It ensured safety for vulnerable family, friends, and freedom seekers. In response to the Fugitive Slave Law, which enabled slaveholders to pursue their “property” with the backing of the federal government, Frederick Douglass appealed to the natural law of self-preservation. He declared that “to act to enslave a fellow man is to declare war against him and to endow him with the right to war—the liberty to kill his aggressor.” Black vigilance groups and protection societies were composed of men and women who operated on this premise as well. They resolved to shield their brethren from slave catchers even at the risk of their own lives.[3]

Armed freedom seekers leaving Maryland in 1857 (House Divided Project)

Third, freedom seekers essentially had no rights and were not usually given the opportunity to testify or present evidence, which left men and women with few alternatives. Black leader William Parker said, “The Laws for personal protection are not made for us, and we are not bound to obey them. If a fight occurs, I want the whites to keep away. They have a country and may obey the laws…. But we have no country.”[4] Black people were not legally US citizens. Accordingly, many Black abolitionists who wanted the United States to be their home believed that physical violence was the only means of solidifying their citizenship. Fourth and finally, Black abolitionists argued that the principles of the Fugitive Slave Law contradicted the laws of God. Indeed, the biblical scripture proclaimed: “Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escaped from his master unto thee.” Black leader Jermain Loguen was a freedom seeker turned station master on the Underground Railroad. He declared, “I owe my freedom to the God who made me, and who stirred me to claim it against all other beings in God’s universe…. I received my freedom from Heaven, and with it came the command to defend my title to it.”[5] For an enslaved people who survived on biblical principles, such scripture carried significant meaning and may have been their most important tenet. Often scholars discuss the Underground Railroad solely in terms of heroic acts of escape; but fleeing often required fighting. Not talking about the embrace of force by Black abolitionists can feel dishonest. It can make it seem as if the Civil War was a spontaneous and unfortunate outcome. But human bondage was warfare. In a speech at Oberlin College, Black educator and abolitionist Lucy Stanton declared, “Slavery is the combination of all crime. It is War.”[6]

In a free North and enslaved South, geography played a major role in protective violence. Because of the proximity of Pennsylvania to the bordering slave state of Maryland, many freedom seekers sought safety and freedom over the state line. Scholars believe Pennsylvania had the largest number of Black runaways in the North. Slave catchers, aware of safe havens, monitored the North/South border states and made quite a business of returning freedom seekers. In response to kidnappings and the general assault on Black residents, people like Eliza and William Parker became infuriated and formed a Black-led group, the Lancaster self-protection society. In a collective stance, a group of freedom-seeking women and men formed this vigilance or mutual protection organization in Christiana, PA (a border town) and resolved to “prevent any of brethren being taken back to slavery, [even] at the risk of our own lives.”[7]

The Parkers’ reputation brought four freedom seekers (Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond) to their door in the late 1840s. The men sought haven in the Parker’s home at Christiana in southern Pennsylvania on their path north. Willingly, the Parkers agreed to house and protect them. But it was not long after their arrival, on September 11, 1851, that Edward Gorsuch, the Maryland slaveholder in search of his slaves, arrived with his son, his nephew, a deputy US marshal, and his assistants to claim his “fugitive property.” When Gorsuch and his men confronted the Parkers at their home, they exchanged words and a standoff ensued. Parker instructed the fugitive slaves to not be afraid or give in to any slaveholder: he would fight for them to the death if necessary.[8]

The Parkers had prepared for such altercations. In the event that slave catchers were near or whenever trouble arose, Eliza was responsible for sounding the alarm to alert the self-protection society. When it became clear that Gorsuch was unwilling to forfeit his property, Eliza suggested to Parker that assistance was needed. She thought now was a good time to signal to their friends to come to their aid. Parker agreed. Without hesitation, Eliza moved into action. She headed to their small attic and proceeded to blow a loud horn to signal for assistance.

The Parkers had prepared for such altercations. In the event that slave catchers were near or whenever trouble arose, Eliza was responsible for sounding the alarm to alert the self-protection society.

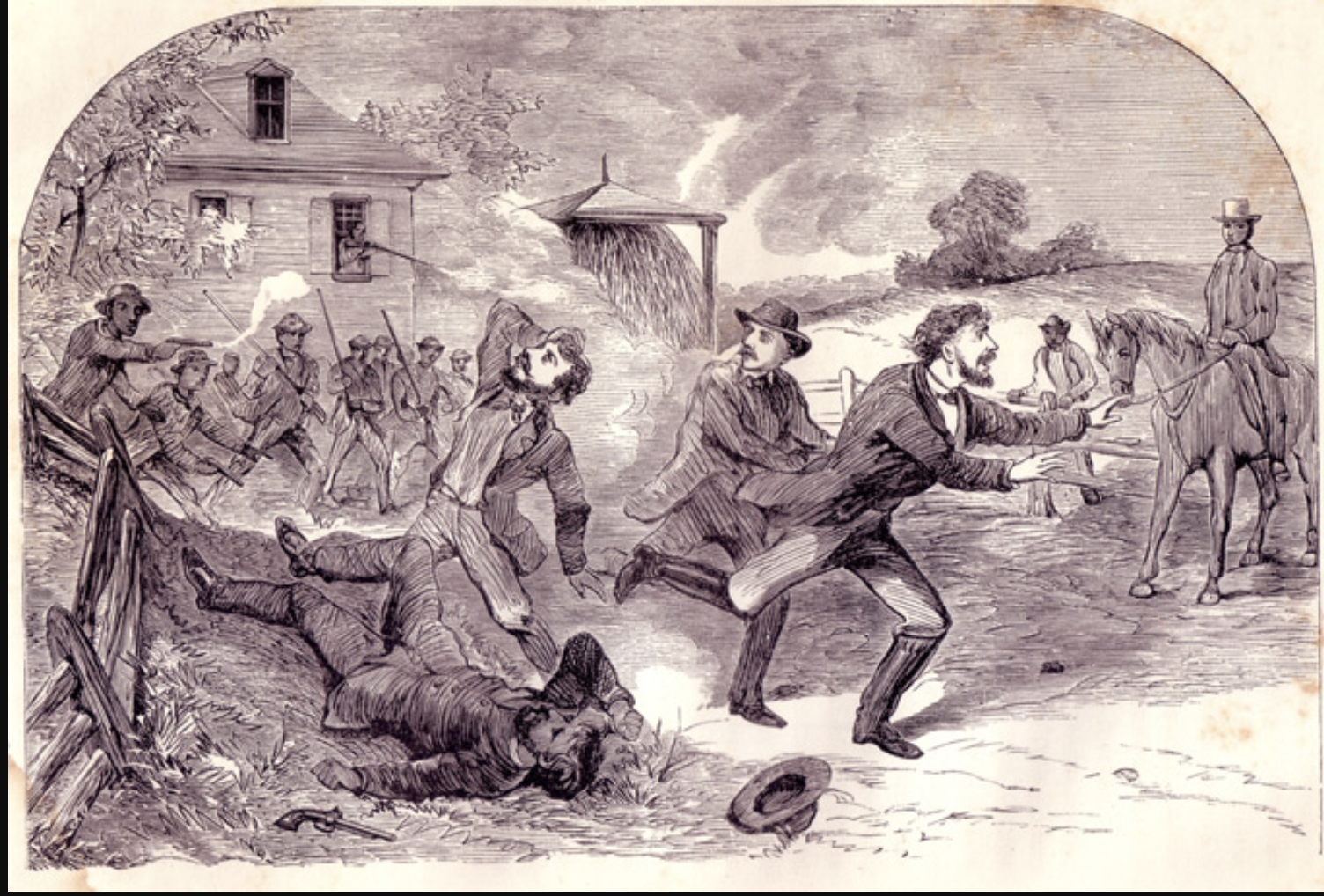

What followed was one of the most significant violent episodes before the Civil War. As the conversation escalated, Parker heaved pitchforks and axes at the white men in an attempt to run them off. At that moment, dozens of Black women and men along with two white Quakers, arrived on the scene. Armed with guns and farm equipment, they surrounded Gorsuch’s men and the US marshal. Outnumbered and out-armed, the marshal fled in terror as shots were fired. In the end, Gorsuch was unwavering, and it led to his death at the hands of his own slaves. Parker claimed that “his slave struck him the first and second blows; then three or four sprang upon him, and, when he became helpless, [they] left him to pursue others.” [9] Gorsuch’s son, Dickinson, was lying on the ground not far away and severely wounded. Parker claims the women of Christiana saw the elder Gorsuch dying and put an end to his misery. Black women made equal use of protective violence. The Parkers and the four enslaved men escaped the scene and fled further north on foot and by boat, briefly stopping at safe houses until they made it to Canada. The charges against the remaining accused local resisters were dropped, and Eliza and her husband were safely reunited with their children. They lived on a 50-acre settlement in Buxton, Ontario where some Parker descendants still reside to this day. Christiana was a major victory in the fight against the Slave Power Arguably, more than any other event apart from John Brown’s raid in 1859, tensions from Christiana also helped to precipitate the coming of the Civil War. As scholar Thomas Slaughter concludes, the Civil War “grew in the political soil fertilized by Edward Gorsuch’s blood.”[10]

“The Christiana Tragedy” by John Osler in William Still, The Underground Railroad (1872) (House Divided Project)

John Anderson and other Black leaders had to make agonizing decisions and develop effective strategies to enforce their freedom. How and why Black abolitionists used violence deserves more attention and scholarship. Black emancipation and even Black equality had to be forced. These moments in history present hard lessons. As Frederick Douglass once said, “The American public…discovered and accepted more truth in our four years of Civil War than they learned in forty years of peace.”[11] The truth held in force and violence is an invaluable lesson that hopefully, if learned, need not be repeated.

Further Reading

- Bonner, Christopher. Remaking the Republic: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

- Byrd, Brandon R. The Black Republic: African Americans and the Fate of Haiti. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

- Jackson, Kellie Carter. Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

- Commander, Michelle D. Unsung: Unheralded Narrative of American Slavery and Abolition. New York: Penguin Press, 2021.

- Forbes, Ella. But We Have No Country: The 1851 Christiana, Pennsylvania Resistance. Cherry Hill, NJ: Africana Homestead Legacy, 1998.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and the Racial Violence in the Antebellum North. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Discussion Questions

- Why might some scholars and teachers have been reluctant to emphasize the violence central to Black resistance against slavery?

- According to Kellie Carter Jackson, what were the four basic principles used to justify violent Black resistance to American slavery?

- How does the Christiana resistance in 1851 illustrate several of Jackson’s main contentions?

[1] The Toronto Globe, July 5, 1861.

[2] North Star, September 5, 1850.

[3] Kellie Carter Jackson, Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), 78.

[4] Ella Forbes, But We Have No Country: The 1851 Christiana, Pennsylvania Resistance (Cherry Hill, NJ: Africana Homestead Legacy, 1998).

[5] The Rev. J. W. Loguen, as a Slave and as a Freeman. A Narrative of Real Life (Syracuse, NY: J. G. K. Truair, 1859), 392-3.

[6] Lucy Stanton, “A Plea for the Oppressed,” Oberlin College, 1850.

[7] William Parker, “Freedman’s Story,” The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 17 (March/February 1866), 161.

[8] Parker, “Freedman’s Story,” 283.

[9] Frederick Douglass’ Paper, September 25, 1851.

[10] Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and the Racial Violence in the Antebellum North (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 182.

[11] Jackson, 159.

Author Profile

KELLIE CARTER JACKSON is the Michael and Denise Kellen 68’ Associate Professor in the Department of Africana Studies at Wellesley College. She is the author of the award-winning book, Force & Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. Her essays have been featured in The New York Times, Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, NPR, and other outlets. Carter Jackson serves as a Historian-in-Residence for the Museum of African American History in Boston and is commissioner for the Massachusetts Historical Commission. She is the host and executive producer of “You Get a Podcast!: The Unauthorized Study of the Queen of Talk” and co-host of the Radiotopia podcast “This Day in Esoteric Political History.” Carter Jackson’s newest book is We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance to White Supremacy (Basic Books).

KELLIE CARTER JACKSON is the Michael and Denise Kellen 68’ Associate Professor in the Department of Africana Studies at Wellesley College. She is the author of the award-winning book, Force & Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. Her essays have been featured in The New York Times, Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, NPR, and other outlets. Carter Jackson serves as a Historian-in-Residence for the Museum of African American History in Boston and is commissioner for the Massachusetts Historical Commission. She is the host and executive producer of “You Get a Podcast!: The Unauthorized Study of the Queen of Talk” and co-host of the Radiotopia podcast “This Day in Esoteric Political History.” Carter Jackson’s newest book is We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance to White Supremacy (Basic Books).