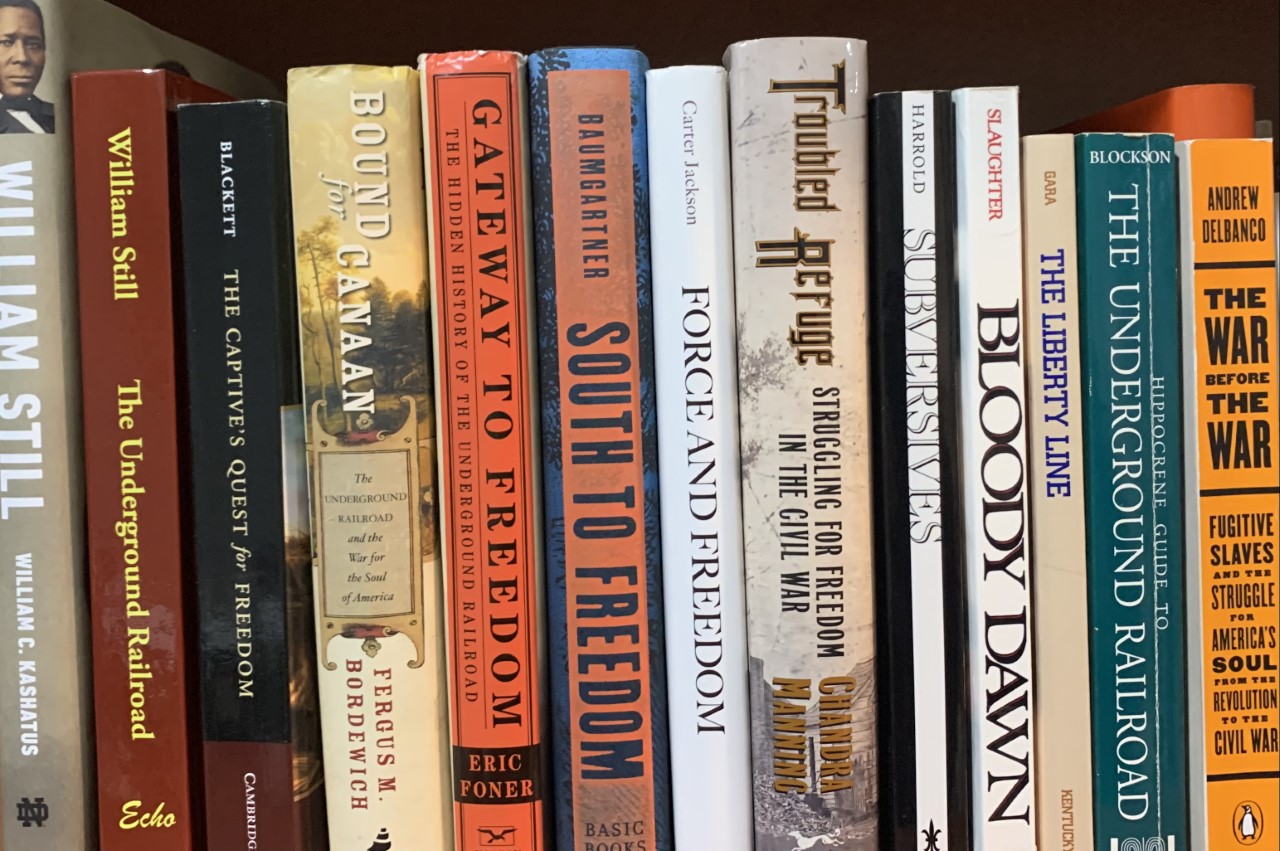

Banner image: Building on the foundations laid by William Still and other Underground Railroad veterans, successive generations of scholars have shed new light on the resistance to American slavery (photo: Matthew Pinsker)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

The earliest writings that reference activities which mirror the operations of the Underground Railroad were created by formerly enslaved African Americans who sought freedom. In these autobiographies, the authors shared the story of their escapes and the support they received from sympathetic individuals during their journeys. Frederick Douglass in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) was among the first to write about his life of enslavement and his journey to freedom. While he did not provide specific details about the help which he had received when leaving Maryland, Douglass acknowledged having been aided by anti-slavery activist David Ruggles once he safely reached New York. Ruggles also facilitated Douglass’s marriage and relocation to New Bedford, Massachusetts. Douglass soon connected there with other abolitionists and settled into his life as a free man.[1]

“Thank Heaven, I remained but a short time in this distressed situation. I was relieved from it by the

humane hand of Mr. DAVID RUGGLES, whose vigilance, kindness, and perseverance, I shall never

forget.” –Frederick Douglass, Narrative (1845) (House Divided Project)

Along with Douglass’s book, abolitionists helped published several other volumes in the 1840s and 1850s offering more details about the process of escape and the aid received by freedom seekers. The most detailed accounting of escape involving the Underground Railroad was provided in the Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851). [2] Brown was married and living in Richmond, Virginia when his wife and children were sold and sent further south. He vowed to seek his freedom and with the support of anti-slavery sympathizers was sealed in a box and shipped by train to the offices of the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society. After a 27-hour journey, he was released from the crate by William Still and others active in the Pennsylvania vigilance organization.

Additional portrayals of freedom seeking follow the experiences of flights from Maryland (Samuel Ringgold Ward and James W.C. Pennington),[3] Georgia (William and Ellen Craft),[4] Tennessee (Jermain Loguen),[5] Kentucky (Josiah Henson, William Wells Brown, and Henry Bibb),[6] and North Carolina (Harriet Jacobs).[7] In each instance support was provided to these freedom seekers at some point during their journey to freedom. Most traversed southern territory on their own only receiving aid after they reached the North. One exception was Harriet Jacobs who described in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) how her escape was aided by family and friends in North Carolina. Also, when Frederick Douglass wrote a second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), he provided more details of the important help he received from Baltimore’s African American community. Each of these volumes sought to highlight the inhumanity of enslavement, the desire to gain freedom by the enslaved, the travails of acting on this desire, and the aid provided as they made their journey northward. All were produced before the start of the Civil War and highlighted the willingness of the authors to risk seeking freedom despite the possibility of repercussions if they failed. Although the Underground Railroad is not often referred to specifically, there are parts of each journey which are dependent on the help of sympathetic individuals. The biography of Isaac T. Hopper produced by the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child highlighted elements of the fugitive aid network, however, and drew from Hopper’s previous newspaper accounts of freedom seekers, “Tales of Oppression.” Child greatly admired the dedicated Philadelphia Quaker who had served as treasurer of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York, and who became a figure some have labeled the “Father of the Underground Railroad.”[8]

After the conclusion of the Civil War, publications referencing the Underground Railroad generally took a different direction. The main authors or subjects were no longer individuals seeking freedom, but rather the people who provided support in one way or another.

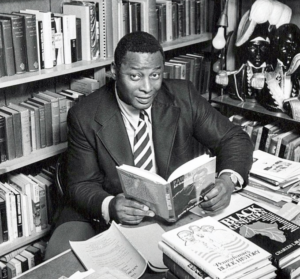

After the conclusion of the Civil War, publications referencing the Underground Railroad generally took a different direction. The main authors or subjects were no longer individuals seeking freedom, but rather the people who provided support in one way or another. Sarah Bradford produced the earliest of these works, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (1869), which highlighted the numerous accomplishments of Harriet Tubman. The intrepid efforts of Tubman as a conductor on the Underground Railroad took center stage in the volume and added to her reputation as a legendary figure at the heart of some of its most significant successes. William Still featured Harriet Tubman and her work with the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee in his book The Underground Railroad (1872). Tubman was also one of more than 800 freedom seekers Still helped. Still’s book was significant in that it captured the first-hand accounts of freedom seekers as they traveled north by way of Philadelphia. It provided a record of their names, where they came from, why they left, as well as the help and challenges they encountered during their travels.[9]

Like Still, Levi Coffin was a stationmaster. His reminiscences about his decades of helping freedom seekers offered a perspective on the operation of the Underground Railroad in Ohio and Indiana. Often described as the “President of the Underground Railroad,” Coffin revealed in his memoir the secrecy and subterfuge characteristic of its operation as well as the organization and resources required to sustain the work.[10] In A Woman’s Life-Work: Labors and Experiences of Laura S. Haviland (1887) the author elucidated her role as a conductor and stationmaster. As a conductor Haviland traveled south numerous times to abet the escape of enslaved men and women. Like many directly involved in the Underground Railroad. Haviland felt it her obligation to directly combat the injustices of enslavement.[11]

Subsequent to Haviland, publications about the Underground Railroad were not crafted by participants in the movement but by scholars investigating its operations. An early regional study from this perspective focused on southeastern Pennsylvania. Titled History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania and created by Robert C. Smedley in 1883, this work provided an in-depth explanation of the stationmasters and freedom seekers essential to understanding the effective operation of the system in the Keystone state. With a wider national view and probably the most influential volume from an academic perspective was The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (1898) by Wilbur H. Siebert a professor at Ohio State University. The publication represented more than fifty years of work by Siebert to document the operation of this system. His data gathering included corresponding with and interviewing former Underground Railroad participants through which he crafted a sense of the methods, routes, and strategies emblematic of its operation. His work with its focus on conductors and stationmasters became the standard for interpreting the Underground Railroad for several decades.[12]

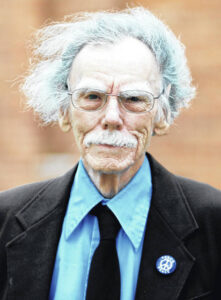

It is not until 1961 with the publication of The Liberty Line by Larry Gara that modern scholars started questioning the perspectives promulgated by Siebert. In particular, Gara argues for greater recognition of the efforts by freedom seekers.

Larry Gara (1922-2019) (Wilmington College)

It is not until 1961 with the publication of The Liberty Line by Larry Gara that modern scholars started questioning the perspectives promulgated by Siebert. In particular, Gara argues for greater recognition of the efforts by freedom seekers. In Gara’s view the Underground Railroad as described by Siebert did not have an impact until long after freedom seekers made their decisions to risk leaving. They navigated southern territory largely on their own until they reached free territory and the support of stationmasters north of the Mason-Dixon Line. While there were a few southern stationmasters like Thomas Garrett of Delaware, they were the exceptions. Gara also questions Siebert’s data-gathering methods, suggesting that the memories of the individuals whom he contacted were not trustworthy. Very likely, Gara asserts, they embellished their recollections to ensure their positive place in history as change agents. In raising these questions, Gara shifts the emphasis of studying the Underground Railroad to a greater focus on the courage and importance of freedom seekers.

Gara’s emphasis on freedom seekers is echoed in the work of Charles Blockson in The Underground Railroad (1994), which focuses on the courage, physical challenges, and dangers associated with the decision to escape that were central to the individual stories he highlights. This book followed an important 1984 article written by Blockson in National Geographic where he also highlights the courage of African American freedom seekers, the historical importance of the Underground Railroad, and the need for increasing examination of its participants and operations.[13] Using a different perspective, John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger in Runaway Slaves (1999) apply their study of runaway advertisements to better understand the phenomenon of seeking relief from the rigors of enslavement. They conclude that while running away frequently occurred, only a small portion of those individuals made use of the Underground Railroad. Most headed to nearby urban areas or neighboring wooded areas and after a few days or weeks returned. In their view, using the Underground Railroad was a small part of a larger movement to resist enslavement by the enslaved.[14]

Activists providing support to freedom seekers have been the focus of several subsequent publications. Catherine Clinton and Kate Clifford Larson each produce important works examining the motivation and courage of Harriet Tubman.[15] Stationmaster Levi Coffin’s decades-long participation in the organization is the focus of Charles Ludwig in Levi Coffin and the Underground Railroad (2004 ed.). While J. Blaine Hudson highlights other participants in the system in his Encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad (2015). Graham Russell Hodges analyzes the tireless efforts of a sometimes-overlooked activist in his publication David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City (2010). A much-needed biography of the more widely recognized William Still along with an analysis of the characteristics of the freedom seekers described in his book comes from William C. Kashatus, William Still: The Underground Railroad and the Angel at Philadelphia (2021). But one of the best overall narratives about the origins of the Underground Railroad and the figures key to its operation is Bound for Canaan (2005) by Fergus M. Bordewich. In his assessment, the Underground Railroad was the nation’s first interracial civil rights movement functioning as a loose network of freedom seekers and a cross-section of individuals opposed to slavery.[16]

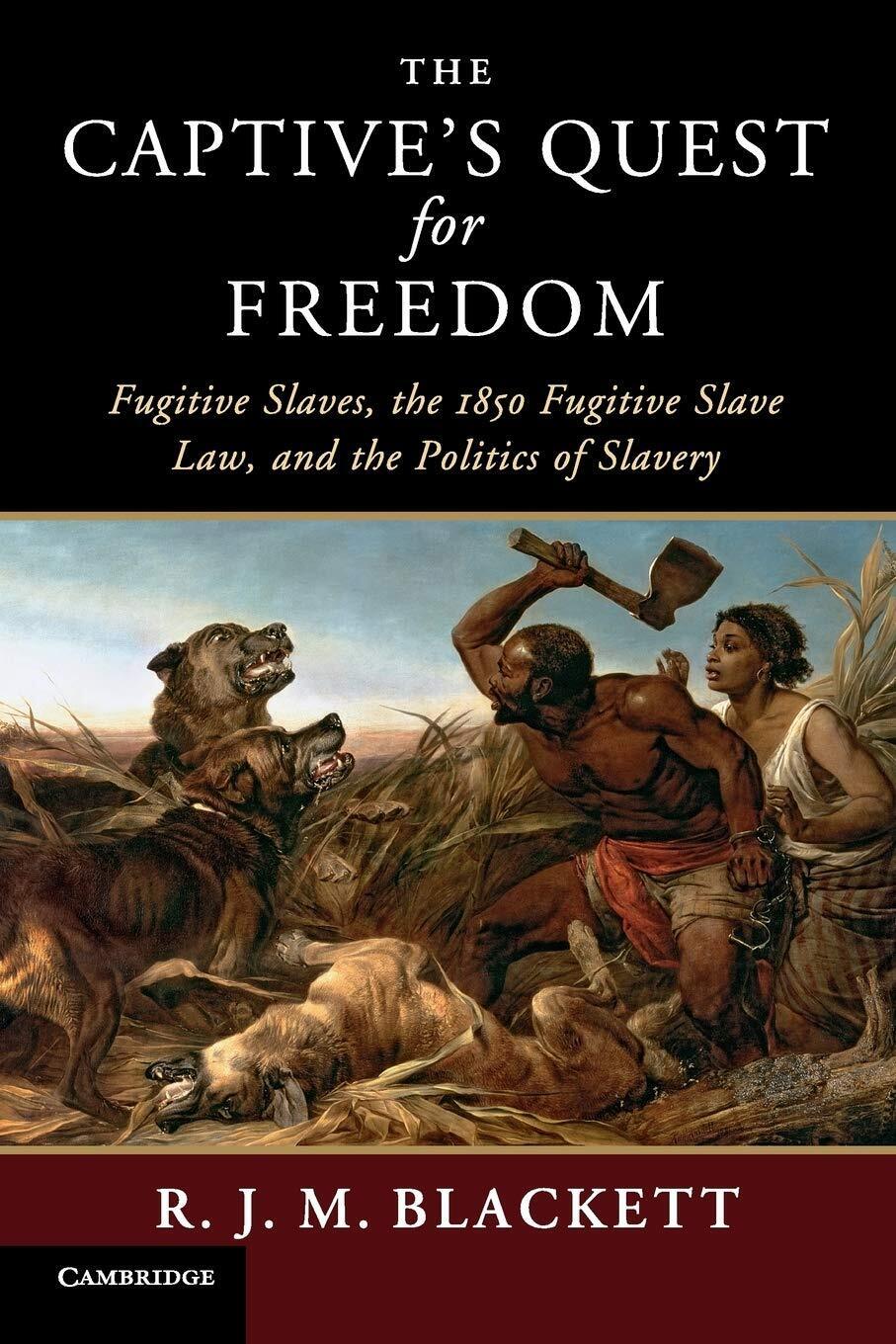

The collaboration which Bordewich describes characterizes the dash for freedom that 77 men and women took aboard the ill-fated vessel the Pearl in Washington, DC. Mary Kay Ricks details the plan, their capture, and fate in Escape on the Pearl (2007). Efforts like the attempt made by the Pearl fugitives took elaborate planning and sophistication even though it failed. Organizations such as the various New York vigilance committees stood ready to support freedom seekers, like those on the Pearl, once they reached northern cities like New York. The story of how these interracial committees defied federal laws, the courts and local officials and helped thousands of freedom seekers is the focus of Eric Foner’s Gateway to Freedom (2015). In that book, Foner uses the records of Sydney Howard Gay, a journalist and vigilance leader, to provide important new insights into inner workings of the network and the collaboration between Black and white New Yorkers. He reminds us in the process that vigilance committees operated in numerous cities and New York’s sometimes-competing groups offer an example of the mode of operation elsewhere.[17] Communication between these anti-slavery groups especially within the African American community flowed at national fraternal and religious organizations meetings. In between conducting official business attendees exchanged information about their work as Underground Railroad supporters. In Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad (2013), Cheryl Janifer LaRoche brings to the fore the critical role that free black communities played in aiding freedom seekers and the lines of communication they maintained through various organizations. R.J.M. Blackett echoes the importance of Black communities north and south in the process of freedom seeking in two seminal studies: Making Freedom (2013) and The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018). Both freedom seekers and Black communities opposed slavery and used what resources they had, including sheltering runaways or making the decision to escape, as ways of asserting their resistance to fugitive slave laws and the institution of slavery itself. In the process, Blackett asserts they had a major impact on the national debate over slavery.[18]

Alice Baumgartner turns the focus to a different region of the country in her exploration of freedom seekers headed toward Mexico in South to Freedom (2020). Enslaved individuals living in Texas and other south-central states believed antislavery laws in Mexico made that nation a potential promised land and traveled south to freedom, not north. Their flights to Mexico were an important factor in Texas’s push for independence from Mexico. As a regional study of underground railroad activism, Baumgartner’s work reflects the growing number of geographically specific studies being produced. Many of the works focus on efforts based in the middle of the country such as Keith Griffler’s work Front Line of Freedom (2004) and Ann Hagedorn’s Beyond the River (2002) which both highlight anti-slavery activism along the Ohio River. Blaine Hudson similarly explores Underground Railroad efforts in an adjacent southern state in Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland (2002). While Carol E. Mull, Julia Pferdehirt, and Lowell J. Soike bring to light similar activities in Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa.[19]

But the majority of the regional studies focus on the Atlantic seaboard led by William Kashatus’s Just Over the Line (2002) which casts a critical eye on Quaker views on slavery in Chester County, Pennsylvania. William J. Switala’s work highlights key routes and participants in Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania. Stanley Harrold’s Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (2003) offers an analysis of the thinking underlying Underground Railroad activism in and around that city. Underground Railroad efforts in Virginia receive attention from Cassandra Newby-Alexander in Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad (2017) as she details the constant active resistance of the enslaved by using the James River and other water routes as pathways to freedom. The importance of maritime escape paths is further reinforced in David Cecelski’s The Waterman’s Song (2012) and Timothy Walker’s edited volume Sailing to Freedom (2021). Other regional studies look at the impact of the Underground Railroad as far north as New Hampshire by Michelle Arnosky Sherburne and as far west as Nebraska by James Patrick Morgans.[20]

In Passages to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in History and Memory (2004) editor David Blight reminds us of the enduring place which the underground railroad has had in American historical memory.[21] It has impacted public discourse in the past and the present concerning the meaning of enslavement and freedom. It has further sparked numerous examinations of its operation and meaning. As it was in the 1800s, Underground Railroad operations remain a complex process to unravel and characterize as they had unique aspects in different times and geographic locations in the nation. While much has been written about the Underground Railroad and its participants, there is still more to learn.

Discussion Questions

- Who pioneered published writings about the Underground Railroad?

- Why was Larry Gara’s work on the Underground Railroad so important?

- How has the focus of Underground Railroad scholarship shifted in recent years?

Citations

[1] Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845).

[2] Brown’s first memoir, published in 1849, was ghostwritten by Charles Stearns; Narrative of Henry Box Brown (Boston: Brown and Stearns, 1849). Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (Manchester, UK: Lee and Glynn, 1851).

[3] Samuel Ringgold Ward, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro (London: John Snow, 1855); James W.C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith (London: Charles Gilpin, 1849).

[4] William and Ellen Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom (London: William Tweedie, 1860).

[5] Jermain Loguen, The Rev. J.W. Loguen, as a Slave and as a Freeman (Syracuse, NY: J.G.K. Truair, 1859).

[6] Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson (Boston: A.D. Phelps, 1849); William Wells Brown, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1847); Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself (New York: Published by the Author, 1849).

[7] Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Boston: For the author, 1861).

[8] Lydia Maria Child, Isaac T. Hopper: A True Life (Boston: Jewett, 1853).

[9] Sarah H. Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (Auburn, NY: WJ Moses, 1869); William Still, The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872).

[10] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, the Reputed President of the Underground Railroad (Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke, 1880).

[11] Laura S. Haviland, A Woman’s Life-Work (Chicago: C.V. Waite, 1887).

[12] R.C. Smedley, History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania (Lancaster, PA: Office of the Journal, 1883); Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad: From Slavery to Freedom (New York: MacMillan, 1898).

[13] Charles L. Blockson, “Escape from Slavery: The Underground Railroad” National Geographic vol. 166, no. 1 (July 1984): 3-39; Charles L. Blockson, Hippocrene Guide to the Underground Railroad (New York: Hippocrene, 1994).

[14] John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

[15] Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom (New York: Little, Brown, 2004); Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero (New York: Random House, 2004).

[16] Charles Ludwig, Levi Coffin and the Underground Railroad (orig. 1975; Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2004 ed.); J. Blaine Hudson, Encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015); Graham Russell Gao Hodges, David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2010); William C. Kashatus, William Still: The Underground Railroad and the Angel at Philadelphia (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, 2021); another recent notable Still biography comes from Andrew K. Diemer, Vigilance: The Life of William Still, Father of the Underground Railroad (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022); Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad/Harper Collins, 2005).

[17] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: William Morrow, 2008); Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015).

[18] Cheryl Janifer Laroche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014); R.J.M. Blackett, Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013) and The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[19] Alice L. Baumgartner, South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 2020); Keith P. Griffler, Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004); Ann Hagedorn, Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002); J. Blaine Hudson, Fugitive slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002); Carol E. Mull, The Underground Railroad in Michigan (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010); Julia Pferdehirt, Freedom Train North: Stories of the Underground Railroad in Wisconsin (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2011); Lowell J. Soike, Necessary Courage: Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle against Slavery (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2013).

[20] William C. Kashatus, Just Over the Line: Chester County and the Underground Railroad (West Chester, PA: Chester County Historical Society, 2002); William J. Switala, Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania: Second Edition (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008); Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2003); Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2017); David S. Cecelski, Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Timothy Walker, Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts, 2021); Michelle Arnosky Sherburne, Slavery & the Underground Railroad in New Hampshire (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2016); James Patrick Morgans, The Underground Railroad on the Western Frontier: Escapes from Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa and the Territories of Kansas, Nebraska and the Indian Nations, 1840-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010).

[21] David W. Blight, ed., Passages to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in History and Memory (Washington DC: Smithsonian Books, 2004).

Author Profile

SPENCER CREW is the Robinson Professor of US history at George Mason University. Crew received a PhD degree from Rutgers University in 1979 and in 2003, he was named to the Rutgers Hall of Distinguished Alumni. He served as president of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center for six years and worked at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution for twenty years. He became the first African-American director of the NMAH in 1994.

SPENCER CREW is the Robinson Professor of US history at George Mason University. Crew received a PhD degree from Rutgers University in 1979 and in 2003, he was named to the Rutgers Hall of Distinguished Alumni. He served as president of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center for six years and worked at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution for twenty years. He became the first African-American director of the NMAH in 1994.