Banner image: Freedom seekers like the family depicted in Eastman Johnson’s 1862 painting, “A Ride for Liberty,” often found state laws to be as relevant as the federal code in determining the outcome of their quest for liberation. (Brooklyn Museum)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

Freedom seekers faced a bewildering array of state laws in their Underground Railroad journeys. Hostile state laws made the experience more difficult, although it never stopped them from trying. Beginning in the 1820s, free states began passing personal liberty laws that extended legal protection to freedom seekers, just as slave states began consolidating their slave property and “slave stealing” laws. Conflict between these legal systems played out on the national stage. The Supreme Court declared many free states’ personal liberty laws unconstitutional in 1842, but free states found other ways to protect freedom seekers.

From colonial days, slave states devoted considerable resources to prevent freedom-seeking. Black people were required to carry proof of status if free, or permission to travel if enslaved. Colonies forbade enslaved people to gather, and often punished whites and free Blacks who entertained enslaved people in their homes. This was not limited to southern colonies. The city of New York forbade enslaved Black people in 1682 from leaving their enslavers’ homes without permission, from gathering together in groups of four or more, or fraternizing with free Blacks and whites. Southern slave colonies authorized slave patrols to roam the countryside in search of runaways and rebels and endowed them with the power to enter plantations and slave quarters without a search warrant. Both the slave patrols and the laws restricting mobility survived the colonial era and became permanent features of the slave states’ legal regimes.[1]

Freedom seeking increased after American independence, especially as the last of the states north of the Mason-Dixon line abolished slavery. Enslavers took measures to secure their property. In addition to securing a Fugitive Slave Clause in the Constitution, they shored up their own legal regimes. In 1805, Virginia made the “carrying away” of enslaved persons a misdemeanor. In 1806, Georgia threatened with capital punishment any enslaved or free Black person who sought to “inveigle, delude, or entice” any enslaved person to run away. Such state laws only reaffirmed a legal regime that already punished “slave stealing” as larceny under the common law.[2]

Freedom seekers in the first decades of the new republic encountered hostile legal regimes in the free states as well. In 1804, Ohio enacted its highly restrictive “Black Laws,” which required Black migrants to register upon arrival in the state and to provide proof of employment and security. Ohio also assisted enslavers reclaiming fugitive slaves by providing arrest warrants and, in 1807, explicitly forbidding Black testimony in cases where either party was white. It was not clear if such laws were intended to discourage migration of Black people generally, or freedom seeking by enslaved persons specifically, but Ohio’s laws were reflective of hostile attitudes in northern states to freedom seeking.[3]

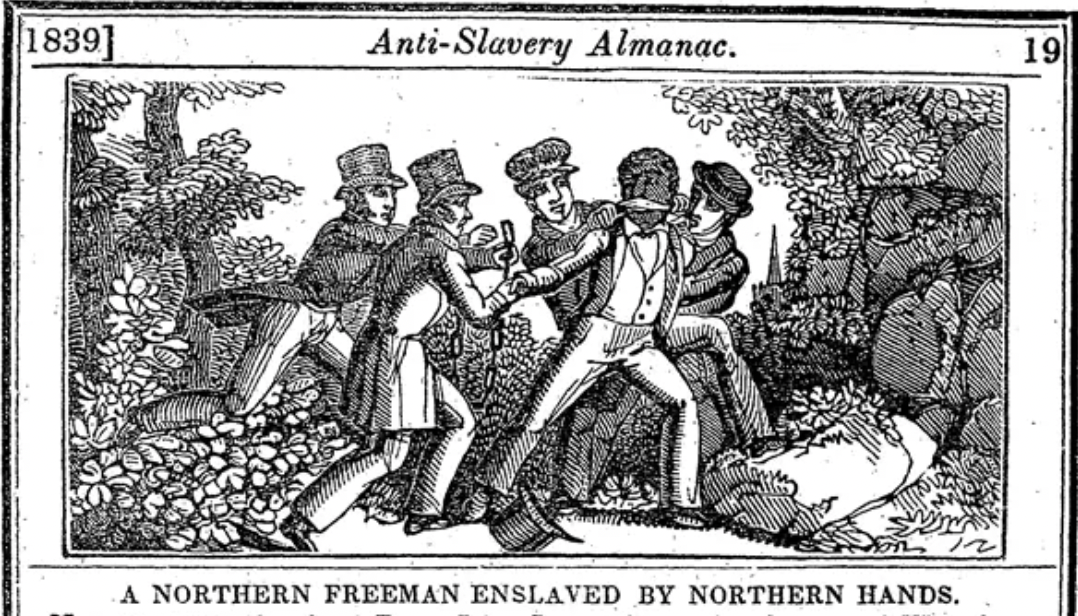

Anti-Slavery Almanac, “A Northern Freeman Enslaved By Northern Hands” (1839) (NPS)

Restrictive laws did not stop freedom seekers. Louisiana’s legislature recognized the problem in 1816 when it passed a law making the ship captains responsible for enslaved people who used ships to escape the state. Ship captains were required to prove the freedom of any Black people on board their ship before a mayor or magistrate, and to stop a vessel upon discovery of any stowaway and deliver him or her to the nearest sheriff or justice of the peace. If a stowaway was discovered on board, the captain was liable for criminal penalties, and bore the burden of proof in demonstrating his innocence in concealing the stowaway.[4]

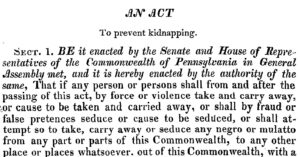

Pennsylvania’s 1820 anti-kidnapping law ushered in a wave of personal liberty laws throughout the North (House Divided Project)

After 1820, northern states adopted new laws, more friendly to freedom seekers. In 1820, Pennsylvania withdrew state support for enslavers. No longer could enslavers rely on Pennsylvania marshals, justices of the peace, judges, or jailors. This proved crippling to enslavers. Other states revised their laws to provide legal protections for alleged fugitives. Indiana in 1824 provided additional securities for people claimed as fugitive slaves by allowing them a jury trial if they claimed freedom. New Jersey passed a law in 1826 that required enslavers to provide a statement under oath in order to receive a warrant and to provide evidence apart from their own testimony to claim an alleged fugitive. Pennsylvania in 1826 adopted a law similar to New Jersey’s but required at least two witnesses to prove the identity of an alleged fugitive. New York in 1828 provided a jury trial for alleged fugitives. These personal liberty laws of the northern states created a more hospitable environment for freedom seekers in free states. They shifted the burden of proof in fugitive slave cases onto enslavers and extended at least a small measure of due process rights to alleged fugitives.[5]

These personal liberty laws of the northern states created a more hospitable environment for freedom seekers in free states. They shifted the burden of proof in fugitive slave cases onto enslavers and extended at least a small measure of due process rights to alleged fugitives.

Southern states, meanwhile, consolidated their laws to aid enslavers. Tennessee revised its criminal code in 1829 to punish those who took an enslaved person, “with or without [their] consent,” from an enslaver. Kentucky passed a law in 1830 making it a crime for any person “seducing or enticing any slave to leave his lawful owner” and depart from the state. In 1835, Georgia and Missouri both specifically targeted free Blacks who assisted enslaved people seeking freedom. Louisiana strengthened its statutes as well, making ship captains civilly liable if their vessels were used to spirit freedom seekers out of Louisiana. In 1842, Missouri clarified its law by specifically making it a crime to “aid or assist in enticing, decoying, or persuading, or carrying away, or sending out of this state” an enslaved person. By the mid-1840s, every slaveholding state had a robust regime of state laws that specifically punished “slave stealing.”[6]

Calvin Fairbank served a total of seventeen years in Kentucky prison for “slave stealing” (House Divided Project)

Slaveholding states also stepped up enforcement of their laws. In 1841, Missouri sentenced three Illinois abolitionists to 12 years in prison for slave stealing. In 1844, a New York abolitionist, Charles Torrey, was sentenced in Maryland for six years for the same offense. In 1846, Calvin Fairbank crossed from Ohio into Kentucky. He convinced Delia E. Webster, a schoolteacher in Lexington, to assist him in aiding Lewis Hayden and his wife and child in escaping from slavery. The escape effort was successful, but Fairbank and Webster were arrested when Fairbank attempted to convey Webster safely back to her home and job in Lexington. Both were convicted. Delia Webster was sentenced to two years, although she was pardoned after two months once she agreed to denounce abolitionism. Fairbank received a 15-year sentence and served four years before being pardoned, thanks to Lewis Hayden, who arranged to compensate his former enslaver in exchange for the pardon.[7] But the defiant Fairbank got arrested again only two years later and ended up serving another 13 years, for a total of seventeen years imprisoned as a convicted “slave stealer” in the Kentucky penitentiary.

The rigorous enforcement of “slave-stealing statutes” was accompanied by national controversy over the northern states’ personal liberty laws. Enslavers complained that these laws unconstitutionally burdened them when pursuing fugitive slaves into the free states. It was certainly true that the free states’ laws raised evidentiary standards for enslavers beyond the requirements of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, and this raised the legal question of whether state law and federal law was in conflict. In 1834, the Supreme Court of New York held that New York’s personal liberty law was unconstitutional because its requirement of a jury trial conflicted with federal law. In New York, the state’s Supreme Court was not the highest court, and the case was appealed to the New York Court for the Correction of Errors. The result was upheld, but Chancellor Reuben Walworth wrote a lengthy opinion arguing that the state’s personal liberty law was valid. In neighboring New Jersey, Chief Justice Horatio Hornblower wrote a lengthy opinion arguing that the state’s personal liberty law took precedence over federal law. The law was, to say the least, unsettled.[8]

New York governor William Seward refused to extradite three Black sailors to face slave stealing charges in Virginia (House Divided Project)

“Slave stealing” statutes also generated constitutional controversy. In 1837, two Maine men sailed out of Savannah harbor with Atticus, an enslaved man. Atticus’s enslavers filed a criminal complaint, and the governor of Georgia requested the Maine sailors’ extradition. Maine’s governor refused to extradite the two men, on the grounds that the affidavit was defective and that the men had been involved in ordinary commerce when in Savannah. It prompted a hot reply from the Georgia governor and resolutions from multiple southern legislatures. In 1839, three free Black sailors helped an enslaved man named Isaac escape Virginia. Governor William Seward of New York refused to extradite the three sailors. He cited technical reasons, but he also justified his decision by referencing international law. Slavery did not exist in New York, Seward reasoned, and since there was no comparable crime of “slave stealing” in the state, there was no basis to extradite. Virginia retaliated in 1841 by passing a law requiring all vessels owned or operated by New Yorkers to submit to a special inspection, for which ship owners would bear the costs. Virginia’s legislature promised to repeal the law if New York would surrender the fugitives and also repeal its personal liberty law. Neither side yielded, however.[9]

Roughly contemporaneously, another extradition controversy occurred regarding Pennsylvania’s personal liberty law. Edward Prigg and a party of slave catchers entered into Pennsylvania in 1837, then captured and forcibly took Margaret Morgan and her children to Maryland, claiming they were the property of a woman named Margaret Ashmore. Pennsylvania indicted Prigg under the criminal provisions of its personal liberty law, but Maryland’s governor was loathe to extradite him. Negotiations between the two states eventually produced a judicial solution. A test case was created and went to the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1842, the Supreme Court ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania that the free states’ personal liberty laws were unconstitutional.[10]

The US Supreme Court’s ruling changed the landscape for freedom seekers. Direct legal protection had been eliminated, although some states, like New York, defiantly kept their personal liberty laws on the books. Another option for free states, however, was to withdraw state support for enslavers who sought to capture freedom seekers. Massachusetts passed the first “non-cooperation” personal liberty law in 1843, following the public outrage over the arrest of freedom seeker George Latimer. The Latimer Law, as it came to be known, forbade state officers to assist in fugitive slave renditions in any manner. Pennsylvania passed its own non-cooperation law in 1847, and Rhode Island followed suit in 1848. Ohio repealed its fugitive slave law but did not go so far as to forbid state officers to assist in fugitive cases.[11]

Enslavers complained bitterly that non-cooperation laws in the North made fugitive slave rendition next to impossible.

Political cartoon from 1840 emphasizing the importance of state laws concerning slavery (Library of Congress)

Enslavers complained bitterly that non-cooperation laws in the North made fugitive slave rendition next to impossible. Enslavers received federal support with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, but that law triggered a northern backlash. In 1855, Massachusetts passed a new personal liberty law that interposed the state between enslavers and freedom seekers. Anyone arrested as a fugitive slave could petition for a writ of habeas corpus from the state supreme court. Either party could also request a jury trial, where a final determination of the alleged fugitive’s status would be made. Slave catchers were liable for imprisonment and fines up to $5,000 for wrongful seizures. Wisconsin passed an identical law in 1857, although it added a section pledging state support for anyone facing criminal charges under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Ohio passed a personal liberty law as well that did not go quite as far. It was essentially a non-cooperation law but added criminal penalties for anyone who attempted to remove an alleged fugitive slave without following federal law.[12]

These new personal liberty laws were a muscular form of state interposition between freedom seekers and enslavers. Another form of interposition was to continue to resist extradition requests. When the governor of Kentucky in 1859 formally requested the extradition of Willis Lago, a free Black man indicted for aiding enslaved people to escape to Ohio, Governor Salmon P. Chase refused to extradite him. Chase’s successor, Governor William Dennison, continued to refuse, in defiance of federal law. In 1861, the U.S. Supreme Court held in the case of Kentucky v. Dennison that the federal government did not have the power to compel governors to extradite people charged with crimes in other states, even if those governors were constitutionally obligated to deliver up fugitives from justice.[13]

By the time of the election of 1860, state laws had altered significantly from the first days of the republic. Notably, many free states had adopted state laws that protected freedom seekers, sometimes in direct defiance of the proslavery federal government. That some free states intensified this resistance in the 1850s was one of the many harbingers of disunion and civil war.

Further Reading

- Baker, H. Robert. Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012.

- Blackett, R. J. M. The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Resistance to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Harold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting over Slavery Before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W.W. Norton, 2015.

- Lubet, Steven. Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Morris, Thomas D. Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780-1861. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

Discussion Questions

- How did northern “personal liberty” state laws provide some help for freedom seekers and their allies? How did southern “slave stealing” state laws attempt to punish and deter freedom seekers and their allies?

- The “bewildering array” of laws which tried to regulate attempted (or accused) escapes from enslavement that author Robert Baker describes in this essay were examples of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century federalism. Why is the complicated nature of American federalism so important for understanding the coming of the Civil War?

Citations

[1] For New York’s 1682 law restricting mobility, see Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776, vol. 1 (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1905), 92. For Virginia’s law of 1672, see William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, vol. 2 (New York: R. & W. & T. Bartow, 1823), 299.

[2] Virginia, “Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia,” in Rights of Things and Persons Section XII, vol. 1 (Richmond, Va: Thomas Ritchie, 1819), 428; Oliver H. Prince, ed., A Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia, vol. 1 (Milledgeville, GA: Grantland & Orme, 1822), 376.

[3] Stephen Middleton, The Black Laws in the Old Northwest: A Documentary History, Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies, no. 152 (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1993).

[4] An Act to prevent the carrying away of slaves, 1816 La. Laws 8 (Feb. 13, 1816).

[5] Lucius Q. C. Elmer, ed., Digest of the Laws of New Jersey. Containing Also the Constitutions of the United States, and of This State, and the Rules and Decisions of the Courts, vol. 1 (Bridgeton, NJ: James E. Newell, 1838), 529; “Personal Liberty Law,” 1825 Pa. Laws 150 (March 25, 1826); “An Act to Prevent Kidnapping,” 1827 NY Laws 348.

[6] John Haywood and Robert L. Cobbs, Statute Laws of the State of Tennessee, of a Public & General Nature, Revised and Digested (Knoxville, TN: F. S. Heiskell, 1831), 246; C.S. Morehead and Mason Brown, Digest of the Statute Laws of Kentucky, of a Public and Permanent Nature, vol. 2 (Frankfort, Ky.: Albert G. Hodges, 1834), 1302; The Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri (St. Louis: J. W. Dougherty, 1845), 359, 1026; Prince, A Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia, 1:801.

[7] Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 51–52, 122; Richard J.M. Blackett, “Resistance to Slavery in Middle Tennessee: Fugitive Slaves, the Underground Railroad, and the Politics of Slavery in the Decade before the Civil War,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 76, no. 4 (2017): 300–341; Blackett.

[8] Many of these judicial opinions are reproduced in Paul Finkelman, ed., Fugitive Slaves and American Courts: The Pamphlet Literature (New York: Garland Pub, 1988).

[9] Michael D. Thompson, “Working on the Docks: Waterfront Labor, Coastal Commerce, and Escaping Enslavement from Charleston, South Carolina,” in Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad, ed. Timothy D. Walker (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), 36–53. Some of the primary sources connected with this affair can be found in William Henry Seward and Frederick William Seward, Autobiography of William H. Seward, from 1801 to 1834: With a Memoir of His Life, and Selections from His Letters from 1831 to 1846 (New York: D. Appleton, 1877).

[10] Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. 539 (1842).

[11] Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780-1861 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), 107–29.

[12] General Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, vol. 1 (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1859), 735; “An Act Relating to the writ of Habeas Corpus,” 1857 Wis. Laws 12; Joseph R. Swan, ed., The Revised Statutes of the State of Ohio, of a General Nature, in Force August 1, 1860, vol. 1 (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1870), 418.

[13] Kentucky v. Dennison, 65 U.S. 66 (1861).

Author Profile

H. ROBERT BAKER is an associate history professor at Georgia State University. He received his bachelor’s degree in history from Pomona College in California, his master’s degree in interdisciplinary studies from the University of Manitoba, Canada, and his doctorate in history from University of California, Los Angeles. He authored two books: Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution (University Press of Kansas, 2012) and The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War. (Ohio University Press, 2006). His area of interest is the influence of historical consciousness on constitutional thinking, as well as the nature of constitutional change over time.

H. ROBERT BAKER is an associate history professor at Georgia State University. He received his bachelor’s degree in history from Pomona College in California, his master’s degree in interdisciplinary studies from the University of Manitoba, Canada, and his doctorate in history from University of California, Los Angeles. He authored two books: Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution (University Press of Kansas, 2012) and The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War. (Ohio University Press, 2006). His area of interest is the influence of historical consciousness on constitutional thinking, as well as the nature of constitutional change over time.

Related Works and Appearances by H. Robert Baker

- Panel on Constitutional History (CSPAN, 2022)