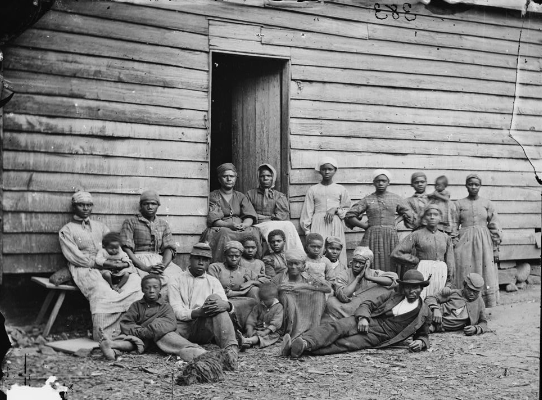

Banner image: The Civil War afforded new opportunities for enslaved people to find freedom behind US Army lines, such as this multi-generational family of “contrabands” in Beaufort, South Carolina photographed in 1862 (colorized by Amanda Donoghue, House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

As war raged along North Carolina’s shoreline, a woman gently settled a basket of eggs into a canoe alongside her children and walked the canoe through twelve miles of coastal waves to a Union Army encampment under the command of Gen. Ambrose Burnside. In some ways she replicated antebellum freedom seekers’ journeys on the Underground Railroad, but unlike most earlier travelers, who were men heading on their own to a northern state or out of the country, she was a woman who, along with her children, fled to a site much closer to home. She and more than 400,000 others escaped to Civil War contraband camps, which sprang up everywhere the Union Army entered the Confederacy and amplified the battle against slavery that earlier freedom seekers had waged on the Underground Railroad.[1]

Since the trans-Atlantic slave trade began in the 1500s, enslaved people resisted bondage. Freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad continued that fight as they carved individual paths out of enslavement. Yet in 1860, the institution of slavery remained strong and poised to grow. Even the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 provided no guarantee of slavery’s demise. After the War of 1812, the Seminole Wars, and the Mexican-American War, US slavery had emerged bigger and stronger. One main difference in the Civil War was an alliance which freedom seekers formed with the Union Army in contraband camps.

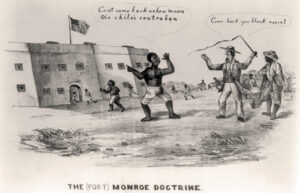

1861 political cartoon, “The (Fort) Monroe Doctrine” (House Divided Project)

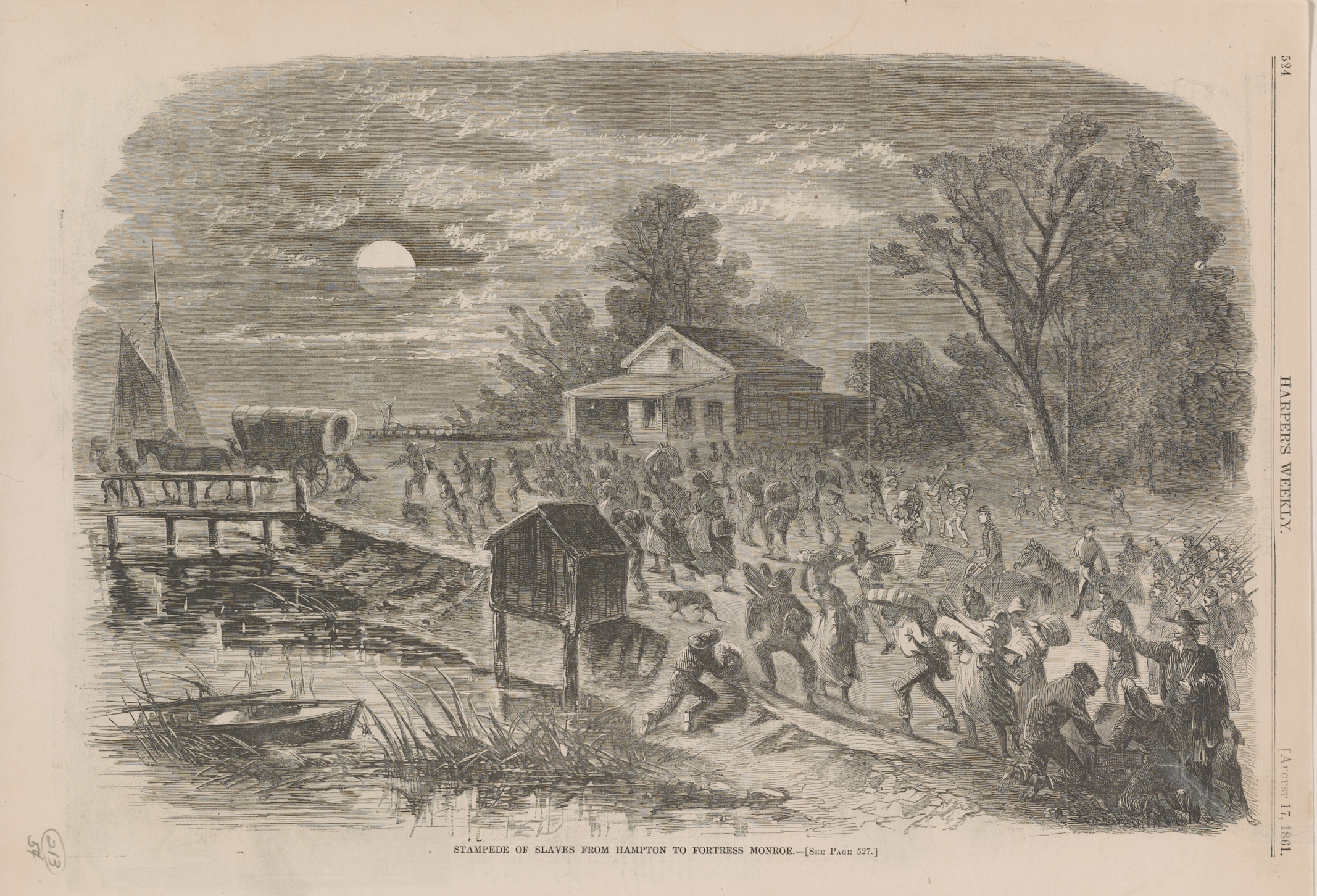

That alliance began in May 1861. Three enslaved men –Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend– had been put to work building Confederate fortifications. When they learned that their enslaver, Confederate Col. Charles Mallory, planned to move them away from their families to labor for the Confederate Army, they ran to the Union Army installation at Fort Monroe, Virginia. It was a risky move. In the daily, low-level war between slaveholders and enslaved people that was slavery, the US government had always sided with slaveholders. Now the three men gambled things would be different. The morning after their flight, Mallory demanded that the commanding officer, Gen. Benjamin Butler, return the men in compliance with the Fugitive Slave Act. Butler countered that Mallory’s use of the men to build fortifications as part of an armed rebellion against the United States permitted their confiscation as contraband property of war. Delighting in the irony, Butler used slaveholders’ own insistence on slave property rights to release the three men from their purported owner. The language stuck: freedom seekers who ran to the Union Army became known as “contrabands,” and the encampments where they spent the war were called contraband camps. [2]

The language stuck: freedom seekers who ran to the Union Army became known as “contrabands,” and the encampments where they spent the war were called contraband camps.

Clustering in the Washington, DC region, cascading down the Atlantic coast to Northern Florida, and dotting rivers and railroad lines in the war’s western theater, contraband camps reduced the distance out of bondage. More than 474,000 African Americans spent at least part of the war in a contraband camp, accounting for between 12 percent and 15 percent of the US slave population and substantially exceeding the number of free African Americans—221,702—living in the northern states in 1860.[3]

The shortened distance emboldened women and children to run. One mother and daughter made a dash for Union lines near Arlington, Virginia in November 1861. On an August day the following year, more than eighty women and children with no food or water, and with clothing hanging in tatters, made their way into Union lines near Fredericksburg. One Tennessee morning in spring 1863, an enslaved grandmother milking a cow caught sight of Union soldiers, gathered up thirty-one children and grandchildren, and clambered onto Union supply wagons heading for LaGrange. Like the North Carolina woman with the basket of eggs, these women were part of the demographic wave rushing into contraband camps. Especially once the Union Army began to enlist African American soldiers, camps consisted overwhelmingly of women, children, and the infirm as healthy, fighting-age men joined the army.[4]

“Contrabands” gathered at Cumberland Landing, Virginia in 1862 (Library of Congress)

Conditions often amounted to a humanitarian crisis because camps were impromptu settlements administered not by professional organizations like the United Nations (not yet in existence), but by a military focused on winning a war. Freedom seekers typically arrived lacking the “food to keep them alive.”[5] Clothing was in short supply, especially for women and children, so it was not long before garments “began to open in large rents or fall off and expose them to winter,” as one superintendent of contrabands in the Mississippi Valley observed.[6] Freedom seekers took shelter in any available space from deserted structures to barracks to drafty tents, but housing shortages persisted.[7] Inadequate sanitation created fetid breeding grounds for disease. A Union general summarized his observations of a camp at Helena, Arkansas by noting that “sickness rages fearfully among them in this unhealthy location,” and he was far from alone.[8] Other humans also posed threats. Union soldiers’ attitudes ranged widely, with some more than willing to rob, cheat, or harm freedom seekers. Confederates raided camps to re-enslave or murder inhabitants.

Despite the dangers, freedom seekers in contraband camps soon built communities. They went to great lengths to keep families together and sometimes to rebuild them. Near Memphis, two sisters separated by sale fifteen years earlier found each other and reunited with one of the sister’s sons whom neither had seen for seventeen years.[9] They built and attended schools where they learned to read from Union soldiers, white or Black northern aid workers, or members of the local free Black community.[10] They also formed worship communities ranging from congregations like the Union Christian Church of Corinth (Mississippi) to female-led prayer meetings in the Carolina lowcountry.[11]

Part of the Corinth Contraband Camp memorial in Mississippi (NPS)

Freedom seekers directly—and crucially—labored for the Union war effort. They repaired and maintained rail lines, worked on riverboats, and loaded and unloaded cargo on docks.[12] They grew food to feed Federal soldiers and cash crops to fill federal coffers. They cared for livestock, repaired burlap sacks for feeding horses on mobile campaigns, and drove mule teams that powered the army forward.[13] They laundered and nursed in Union hospitals.[14] A survey of superintendents of contrabands in the Mississippi Valley revealed that men, women, and children dug, ditched, planted, weeded, hoed, harvested, hauled, distributed, laundered, cooked, nursed, and more, for the Union war effort.[15]

Freedom seekers directly—and crucially—labored for the Union war effort.

They also spied for the Union Army, “heading from thirty to three hundred miles within the enemy’s lines . . . bringing us back important reliable information,” as one official reported.[16] Freedpeople made good spies because they knew the local terrain better than newly arrived soldiers did. Even children spied: one young boy named Charley risked three dangerous trips through the North Carolina countryside to gather intelligence about Confederate encampments and river crossings.[17] On Louisiana’s Atchafalaya River, a Black man led a Union scout on a reconnoiter of Confederate pickets.[18] In the naval clash between the Monitor and the Merrimack in March 1862, Union officers acknowledged that “the most valuable information we received in regard to the Merrimack and the operations of the rebels came from the colored people.”[19]

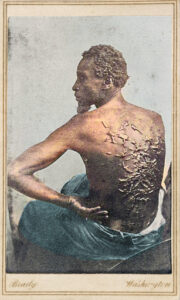

This Louisiana man escaped slavery in 1863 to fight for the Union army (colorized, House Divided Project)

Freedom seekers’ contributions to the Union war effort helped ensure that the war ended slavery. Repeatedly, ordinary Union soldiers confronted the question of who was most likely to aid the war effort: a freedom seeker supporting the Union, or an enslaver who sought the overthrow of it. The answer to that question turned ordinary soldiers into advocates for ending slavery, who in turn strengthened the pro-emancipation wing of the Republican Party in its contest with moderates and conservatives who had initially disavowed abolition as a war aim. Policy evolved over time, from the War Department’s endorsement of Butler’s contraband decision, through Confiscation Acts that permitted the emancipation of enslaved people owned by certain Confederates, through the Emancipation Proclamation freeing enslaved people in Confederate-controlled territory, through an 1864 National Union Party platform that included abolition by constitutional amendment. At each step, freedom seekers’ actions in contraband camps propelled momentum toward general abolition, in contrast to the re-enslavement that had followed previous wars.

Freedom seekers further used their proven usefulness to the war effort to craft a new, although uneven, relationship with the army and federal government. When Union troops were present, freedpeople were safer from attack or re-enslavement, gained a degree of personal mobility, could better protect their families, and gained access to schooling and other aspects of social life prohibited under slavery. Yet when the military’s priorities diverged from freedpeople’s aims, disappointment and heartbreak could result. For all its shortcomings, the new alliance offered real if incomplete gains.

The Underground Railroad did not end when the Civil War began; it shifted gears geographically and demographically and accelerated its pace.

The Underground Railroad did not end when the Civil War began; it shifted gears geographically and demographically and accelerated its pace. Instead of heading for distant states or foreign countries, wartime freedom seekers (disproportionately women and children) exited slavery through contraband camps. Like antebellum travelers on the Underground Railroad, wartime freedom seekers blazed trails for themselves out of bondage, but in contraband camps they did even more. By allying with the Union Army, they linked the destruction of slavery to Union military victory and influenced the progress and outcome of the war and emancipation. Amidst great risk, often in appalling conditions, and despite gaps between hopes for freedom and post-emancipation reality, freedom seekers fundamentally changed the United States from a slaveholding nation to a nation that would need to rebuild its foundations without slavery and with the inclusion of the formerly enslaved. The work that began when Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend set out for Fort Monroe continues to this day.

In 1861, wartime freedom seekers from Virginia and elsewhere helped accelerate a process to remake the foundations of the United States (Library of Congress)

Further Reading

- Berlin, Ira, Steven P. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985-2013.

- Click, Patricia C. Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, 1862-1867. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Manning, Chandra. Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2016.

- Rose, Willie Lee. Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

- Sears, Richard D. Camp Nelson, Kentucky: A Civil War History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002.

- Taylor, Amy Murrell. Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

- Walker, Cam. “Corinth: The Story of a Contraband Camp.” Civil War History 20:1 (1974), 5-22.

Citations

[1] Vincent Colyer’s Report to the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, (hereafter AFIC), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereafter NARA).

[2] Benjamin F. Butler, May 24, 1861, Benjamin F. Butler Papers, Library of Congress; Edward L. Pierce, “The Contrabands at Fortress Monroe,” Atlantic Monthly (Nov. 1861), 626-640.

[3] Ira Berlin et al. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867, ser. 1, vol. 2, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 76–78; Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, “Historical, Demographic, Economic, and Social Data: The United States, 1790–1970” (Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 1997).

[4] Soldier in the 7th Wisconsin Infantry, Dec. 16, 1861, Arlington Heights, VA, E.B. Quiner, Correspondence of Wisconsin Volunteers, Wisconsin Historical Society; Private Constant Hanks, 20th New York Militia, Aug. 8, 1862, Fredericksburg, VA, Constant Hanks papers, Duke University; Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin: The Reputed President of the Underground Railroad (New York: Augustus M. Kelley Reprints of Economic Classics, 1968), 633-35; Chaplain James Alexander, Sept. 1, 1863, Corinth, Mississippi, AFIC Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[5] R. S. King, September 15, 1862, St. Louis, MO, Records of US Army Continental Commands Record Group 393 (hereafter RG 393), NARA.

[6] Col. John Eaton, Superintendent of Contrabands, Department of Tennessee, March 27, 1863, Memphis, TN, NARA.

[7] Julia Wilbur, November 5, 1862, Alexandria, VA, Post Family Papers, University of Rochester; New York World, February 25, 1865; Boston Herald, June 4, 1863; William Slade, Mrs. Daniel Breed, and Mr. George E. H. Day to AFIC, NARA; James Allen Hoobler Collection, Tennessee State Library and Archives; Major Lucien Eaton, May 30, 1863, St. Louis, MO, RG 393, NARA; Contraband Relief Society Circular Letter, February 1863, Missouri Historical Society; Alex Phillips, July 9, 1864, St. Louis, MO, RG 393, NARA.

[8] Benjamin Prentiss, February 28, 1863, and June 16, 1863, Helena, RG 393, NARA.

[9] Laura Haviland, A Woman’s Life-Work: Labors and Experiences (Cincinnati: Walden & Stowe, 1882), 266-67.

[10] Elizabeth Botume, First Days Among the Contrabands (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1893), 41-49, 62, 66; Lewis C. Lockwood, Mary S. Peake, the Colored Teacher at Fortress Monroe (Boston: America Tract Society, 1862.

[11] Responses of Superintendents to Eaton’s Questionnaire, AFIC Records, NARA; Liberator, November 29, 1861; Laura Towne and Roberts Smalls to AFIC, NARA.

[12] J. R. Bigelow to AFIC, NARA; James Morrison MacKaye Papers, Library of Congress.

[13] Lucy Chase to AFIC, NARA.

[14] D. B. Nichols to AFIC, NARA.

[15] Responses to John Eaton Questionnaires, AFIC Records, NARA.

[16] Colyer Report, NARA.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Report of Horace Bell, scout, October 31, 1864, Records of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau (Civil War), NARA.

[19] C.B. Wilder to AFIC, NARA.

Author Profile

CHANDRA MANNING is an American historian and Professor of History at Georgetown who specializes in 19th century US History. She graduated from Mount Holyoke College, received an M.Phil in Irish history and literature from the National University of Ireland, Galway, and a Ph.D. from Harvard in 2002. Her first book, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (Knopf, 2007) won the Avery O. Craven Prize awarded by the Organization of American Historians. Her second book, Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (Knopf, 2016), about Civil War refugee camp, won the Jefferson Davis Prize awarded by the American Civil War Museum for best book on the Civil War.

CHANDRA MANNING is an American historian and Professor of History at Georgetown who specializes in 19th century US History. She graduated from Mount Holyoke College, received an M.Phil in Irish history and literature from the National University of Ireland, Galway, and a Ph.D. from Harvard in 2002. Her first book, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (Knopf, 2007) won the Avery O. Craven Prize awarded by the Organization of American Historians. Her second book, Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (Knopf, 2016), about Civil War refugee camp, won the Jefferson Davis Prize awarded by the American Civil War Museum for best book on the Civil War.