Banner image: A view from the stairs leading up to the Ripley, Ohio home of Underground Railroad activist John Rankin, a historic site now part of the NPS Network to Freedom (Wikipedia)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

In February 1847, slaveholder George Henderson suffered a rash of escapes from his riverfront plantation in Williamstown, Virginia, just across the Ohio River from Marietta, Ohio. At least a dozen African Americans enslaved by Henderson escaped over the course of several weeks, and some of these freedom seekers successfully made contact with the Underground Railroad in Marietta. They may have been motivated by Henderson’s intent to sell some of the enslaved workers on his plantation. There is also reason to believe that some within the plantation community knew how to contact the underground network in Ohio. One member of the community named Isaac had run away successfully in 1837, only to return later to rejoin his wife and daughter in Virginia. Isaac successfully spirited his family away in 1846, an indication that his previous escape had given him knowledge of the Underground Railroad in the area. Henderson was apparently also in the habit of sending his enslaved workers to conduct marketing in Marietta, thus opening another conduit of information that might facilitate future escapes.

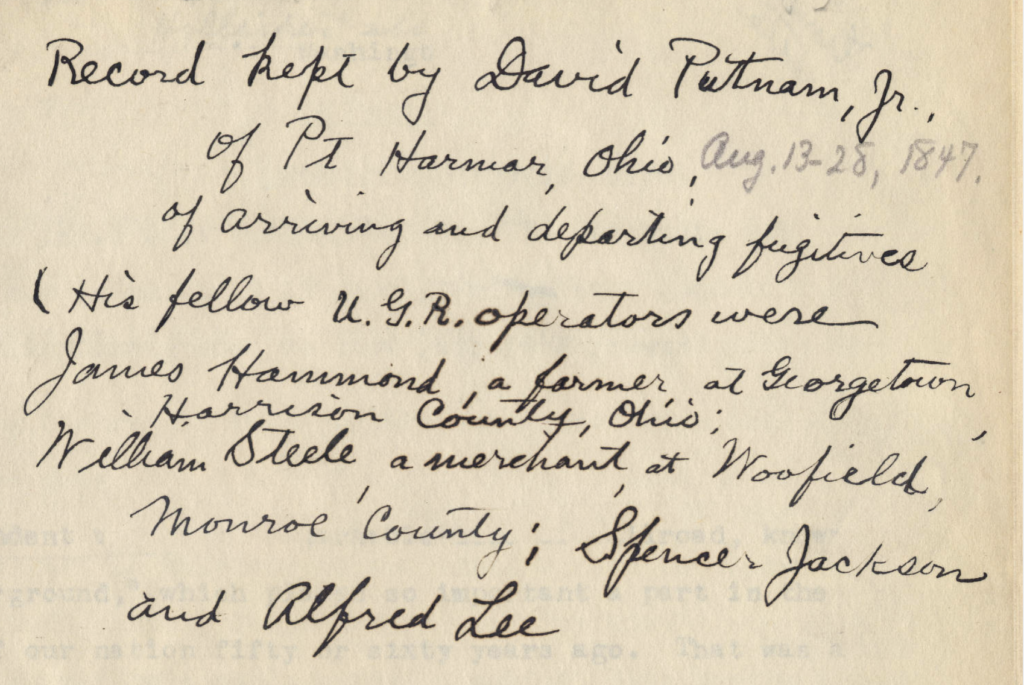

Two of those who fled the plantation were later seen on the property of David Putnam Jr. shortly after their escape. Putnam, grandson of Revolutionary War General Israel Putnam, was part of a wide-ranging underground network that assisted freedom seekers crossing the Ohio River between Gallipolis and Marietta. A fragment of a record book kept by Putnam from the summer of 1847 indicates that he conducted his operations by night, receiving those seeking his assistance between 1 and 2 am and sending them onward at 8 pm the following evening. Though Putnam operated in as much secrecy as possible, local slave catchers knew of his involvement and set a trap for him that February. Willard Green and a hired posse surrounded Putnam’s property while he was harboring Stephen, one of those who had escaped from Henderson. A standoff ensued in which both sides summoned help from associates in Marietta, and a large crowd was soon milling about the property. The darkness and commotion eventually allowed Putnam to slip Stephen and a guide into the crowd, and they successfully escaped. Henderson later sued Putnam, claiming $15,000 in damages, thus placing all of his losses at Putnam’s door. Putnam, however, presented evidence that the escapee at his house that night was not enslaved by Henderson. In the end, Henderson was unable to collect damages.[1]

Cover page from David Putnam’s 1847 Underground Railroad records (Ohio History Connection)

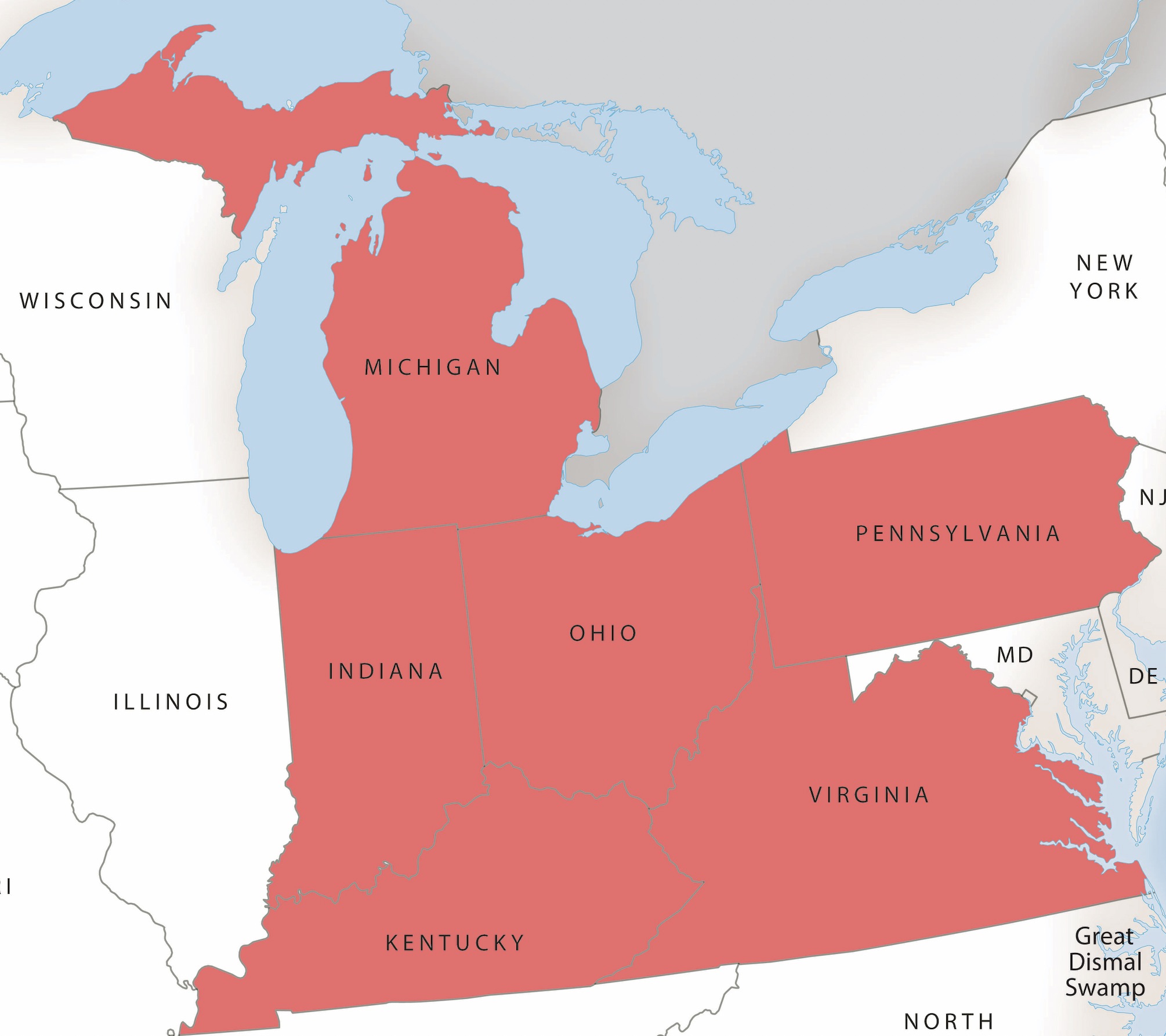

The siege of David Putnam’s house illustrates many of the dynamics that shaped Underground Railroad activities in the Ohio River Valley between Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Evansville, Indiana. Communities on both banks of the river were bound by trade and culture and comprised a borderland in which both people and information moved back and forth to a significant degree. For those enslaved in the counties south of the Ohio River, the greatest challenge lay not in finding their way to the river, or even in crossing it, but in navigating the unknown landscape of the north bank. Most white residents of the border counties of Ohio and Indiana were of southern heritage and shared in the white supremacist and proslavery culture of their southern neighbors. Slave catchers operated on both banks of the river and recruited posses from the underemployed white laborers of Ohio and Indiana. Thus, Underground Railroad activists like Putnam provided crucial assistance to freedom seekers, helping them elude slave catchers and transporting them out of the borderland as quickly and stealthily as possible. For this purpose, activists formed tightly organized networks and operated almost exclusively at night. They worked under continual threat of discovery and legal and violent retaliation. Together they helped thousands of those living in bondage to reach freedom.

For those enslaved in the counties south of the Ohio River, the greatest challenge lay not in finding their way to the river, or even in crossing it, but in navigating the unknown landscape of the north bank.

The counties of southwestern Indiana were strongly proslavery in their cultural orientation, and there is little reliable information about Underground activity in the western part of the state. Closer to New Albany and Jeffersonville, African American activists in those two cities and in free Black communities of Corydon, Beck’s Mill, and Lick Creek, in Harrison County, assisted freedom seekers and connected them with a small interracial network of activists starting at the home of James L. Thompson in Canton, Indiana, northwest of Salem. Thompson guided those seeking freedom northwest over the Muscatatuck River to Farmington. The network extended through Azalia, where activist John Thomas sent freedom seekers north to Carthage. There they turned east into Wayne County and the antislavery stronghold of Newport, Indiana.[2]

George DeBaptiste (Detroit Public Library)

A second network in Indiana was more robust and assisted much larger numbers of freedom seekers. It originated in Madison, Indiana, under the supervision of Black activists George DeBaptiste and Elijah Anderson. DeBaptiste and Anderson had numerous contacts on the Kentucky side of the river who spread word of the promise of freedom and provided assistance with the crossing. From Madison, an interracial group of guides brought freedom seekers through a network of refuges in Jefferson, Ripley, and Decatur counties. The route terminated at the home of Levi Coffin, a well-known activist in Newport, Indiana. From Coffin’s residence, many made the journey to Detroit, or took refuge in the free Black settlements of Cass County in Western Michigan. This network assisted hundreds of African Americans fleeing slavery over several decades, and in retaliation, a white mob recruited from both sides of the Ohio River attacked the Underground Railroad in Madison in 1846 and attempted to shut it down. Nevertheless, on two occasions in the late 1850s, activists fought pitched battles to rescue freedom seekers from the hands of slave catchers.[3]

Two networks in southwestern Ohio guided freedom-seeking African Americans north through the valley of the Great and Little Miami Rivers. One originated in Cincinnati, where a loose group of Black and white activists connected freedom seekers with sympathetic farmers visiting the city to conduct marketing. These farmers concealed those making their escape in farm wagons and carried them north through a dense network of Quaker and free Black settlements between Lebanon and Urbana, Ohio. From the north end of the valley, they were guided northeast across the Scioto River to the Quaker settlement of Alum Creek north of Columbus. From there, freedom seekers struck out for Sandusky and the Ohio Western Reserve. Activists of both races cooperated to rescue freedom seekers in Cincinnati on half a dozen occasions in the 1840s and 1850s but could not prevent the rendition of Margaret Garner and her family in 1856.[4]

The second network extended from Ripley, Ohio to Sardinia, and then northwest, joining the first in the upper end of the Miami River Valley. John Rankin, John Parker, and John Hudson played leading roles in Ripley, and activists in this network fought a running battle against slave catchers and kidnappers across several decades. According to folklore, after several tense confrontations at his home overlooking the town and the Ohio River Valley, Rankin hung a lantern in front of his house so that the enslaved people of Kentucky might mark the location of the path to freedom.[5]

In southeastern Ohio, David Putnam was part of a network of activists between Gallipolis and Marietta. Here too, interracial cooperation was essential, and violence was a constant presence. Free and enslaved African Americans residing in Virginia brought freedom seekers across the river at a dozen locations and passed them to activists who guided them toward Chesterhill. From there a dense network of refuges offered shelter on the way to Zanesville and Putnam, Ohio, which were connected by canal with the Western Reserve. Slave catchers raided the homes of several activists in this area, and dragged one, named Giles, across the river for trial.[6]

A final network extended up both banks of the Monongahela River in western Pennsylvania. Activists in the antislavery strongholds of Uniontown, Washington, and Pittsburgh offered shelter to freedom seekers, who often continued their journeys up into western New York, or northwest towards Cleveland and the Western Reserve. African American crowds in and around Pittsburgh rescued freedom seekers on four occasions between 1841 and 1847.[7]

Slavery, in all its facets, rested on violence. Freedom seekers staked everything on a successful escape and faced catastrophic punishment if caught. Underground activists also faced proslavery violence. Many found their houses surrounded by armed slave catchers. In 1839, slave catchers arrived in the free Black settlement of Cabin Creek in Randolph County, Indiana, a well-travelled refuge. They surrounded the home of an elderly African American couple who were harboring two granddaughters who had escaped from Tennessee. Their grandmother took up a corn cutter and stood in the door of her home, threatening to cut open the first man to cross her threshold. She held the posse at bay until Cabin Creek’s large African American community rallied to her aid. The girls escaped in the confusion. A similar standoff occurred in 1844 at the home of activists William and Martha McIntyre in Adams County, Ohio. A posse of slave catchers arrived and demanded to search the house. As white citizens, the McIntyres had the right to demand a warrant, and a crowd of neighbors warned the slave catchers against a warrantless search. When the posse persisted with their demands, Martha McIntyre lost her temper and threatened to scald the slave catchers with her washing water if they did not leave the premises.[8]

Slavery, in all its facets, rested on violence. Freedom seekers staked everything on a successful escape and faced catastrophic punishment if caught.

In situations in which slave catchers confronted underground activists alone, and without the assistance of neighbors, violent retaliation could be severe. James Thompson was caught at night while guiding two freedom seekers north in 1842. The slave catchers clubbed him off his horse and threatened to “blow his brains out” as they tied the African Americans and led them back to bondage. In Sardinia, Ohio, activist Lewis Pettijohn woke one night to the sound of slave catchers demanding entrance into his home. They proceeded to beat Pettijohn, and then invaded his wife’s bedroom, stripping the bedclothes from her to “see if the negro was not in bed.” Pettijohn and his wife were forced to flee their home. The posse, finding nothing, threatened to burn the town.[9]

This last threat was not entirely idle. Slave catching posses did run rampant on occasion through entire communities, conducting warrantless searches of white and Black households alike and threatening anyone who objected. In 1844 a posse rampaged through Redoak, Ohio looking for men who had escaped from the plantation of Edward Towers. As they approached the home of Black activist Robert Miller, Miller attempted to lead two of those they sought toward safety. When caught, he resisted and was stabbed to death. The posse continued on to the home of Black activist Absalom King, where a gun battle ensued. Towers’s son was shot and killed, and King was wounded before the sheriff arrived to restore order. Later in the day the posse returned, burned the houses of Miller and King, beat white activist Alexander Gilliland and lynched one of the freedom seekers who had defended King’s home.[10]

This climate of pervasive violence shaped the activities of the Underground Railroad in the borderland. Activists organized tight networks that could move freedom seekers between safe refuges by stealth and in the depths of night so as not to alert proslavery neighbors. These networks grew organically out of relationships among like-minded neighbors, religious congregants, and members of anti-slavery associations. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, the arrival of freedom seekers in a neighborhood forced sympathetic residents to utilize such relationships to facilitate the safe passage farther north. Over time and repeated use, these associations had grown by 1840 into dense and well-organized networks of those who had demonstrated their commitment to the cause. Activists guided freedom seekers to the next refuge and returned home before even the earliest risers of their farming communities were up and about. This understanding required trust and coordination between activists of both races. In some cases, it encouraged a racial division of labor in which white activists took advantage of their greater legal rights to harbor freedom seekers in their homes, while black activists played the role of guide and faced the dangers of retaliation at a distance from their families.

Underground Railroad installation (1977) by Cameron Armstrong on the campus of Oberlin College in Ohio (Oberlin College)

Whatever tactics they adopted, the objective of underground activists was the same, to move freedom seekers as quickly as possible to a place of relative safety, where they could be protected, and where their dignity as human beings and their worth as citizens was recognized. For many freedom seekers that place was Canada, but for others, the communities of the upper North served just as well. Slave catchers who ventured into such communities found that they and their recourse to violence met with a very different reception. In 1847, two slave catchers who pursued an African American couple named Roberts to Ohio’s Western Reserve, found that their arrival aroused the local community of Randolph. The door of the couple’s home was barred and the neighborhood was already rallying. The slave catchers professed peaceful intentions, but asked to speak with the couple privately, probably so that they could coerce a voluntary return by threatening violence against family members still in bondage. Members of the community insisted that no such interview could take place unless others were permitted to bear witness. When the slave catchers persisted, members of a growing crowd of neighbors began to fire off muskets in the distance. The slave catchers relented, and returned to the town center, where they were invited to stay the night and attend church in the morning. When they declined, over 200 members of the community formed a procession and “most gently escorted them out of town.”[11]

By the late 1850s, the sentiments on display in Randolph prevailed in an increasing number of communities across the Midwest. Attempts to recapture freedom seekers in Mechanicsburg, Ohio in 1857, and at Oberlin in 1858, resulted in armed confrontations with entire communities in which federal marshals were forced to release the captives. These incidents and the failure of the resulting criminal prosecutions generated national headlines and played a significant role in rising sectional tensions.[12] Thus did the activists of the Underground Railroad turn more and more of the territory of the United States into free soil.

Further Reading

- Blackett, R.J.M. The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, The 1850s Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. New York: Amistad / HarperCollins, 2005.

- Churchill, Robert H., The Underground Railroad and the Geography of Violence in Antebellum America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Coffin, Levi. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin. New York: Arno Press, 1968.

- Griffler, Keith P. Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004.

- Hagedorn, Ann. Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

Citations

[1] Marietta Intelligencer, February 11, 1847; “A Lawsuit in Slavery Times,” n.d., Marietta Public Library; and William B. Summers, “Insuperable Barriers: A Case Study of the Henderson v. Putnam Fugitive Slave Case,” The E.C. Barksdale Memorial Essays in History 13 (1993-1994): 113-146.

[2] E.H. Trueblood, “Reminiscences of the Underground Railroad,” Salem Republican Leader, March 16 and 23 and April 6, 1894, MIC 192, Wilbur H. Siebert Collection (1840-1954), Microfilm Edition, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, OH, Reel 3, Frames 1263-1276 (hereafter Siebert Papers, 3:1263-1276); and John Thomas to Wilbur Siebert, April 5, 1896, ibid., 3:0556-0558.

[3] Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: Amistad, 2005), 1-3 and 202-206; Keith P. Griffler, Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 46-48 and 84-87; Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (New York: Arno Press, 1968), 140-143, 160-170, and 178-186; F.M. Merrel to Wilbur Siebert, March 10, 1895, Siebert Papers, 2:0892-0895; and John H. Tibbets, “Reminiscences of Slavery Times,” Box 2, Folder 2, Theodore L. Steele Papers, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, IN. On rescue attempts, see Madison Courier, July 28, 1856 and New Albany Daily Ledger, May 10, 1860.

[4] Coffin, 304-312 and 335-337; Joel P. Davis to Wilbur Siebert, September 10, 1892, Siebert Papers, 9:0929-0939; J.H. Mendenhall, “Sketch of the Origin, Use, and Method of Operating the Old Underground Railroad,” ibid., 2:0926-0935; Mrs. Norman Dakin to Wilbur Siebert, October 12, 1898, ibid., 9:0912-0915; Excerpt from a Biography of Abraham Allen, n.d., ibid., 9:0897-0902; and Mark Haynes to Wilbur Siebert, September 12, 1892, ibid., 9:0921-0923. On rescues, see Paris, KY Western Citizen, July 9, 1841; Philanthropist, August 9, 1843; Cincinnati Gazette, February 19, 1845 and May 29, 1860; National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 19, 1851; and Liberator, October 28, 1853. On Garner, see New York Tribune, March 3, 1856.

[5] Ann Hagedorn, Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002); Narratives of the Sufferings of Lewis and Milton Clarke (Boston: Bela Marsh, 1846), 58; Coffin, 262-264; Interview of R.C. Rankin, April 8, 1892, Siebert Papers, 9:0399-0414; Isaac Beck to Wilbur Siebert, December 26, 1892, ibid., 9:0538-0552; and Henry Huggins to Wilbur Siebert, October 30, 1895, ibid., 9:0560-0567. The story of Rankin’s lantern was first discussed in sources dating from the early 20th century. See Hagedorn, 305 note 202.

[6] “Record of David Putnam, Jr., of Arriving and Departing Fugitives,” August 13-28, 1847, Siebert Papers, 11:1160 and 1163-1164; N.B. Sisson to Wilbur Siebert, September 16, 1894, and Sisson to Siebert, n.d., ibid., 10:0049-0055 and 10:0058-0066; Martha Millions to Wilbur Siebert, March 9, 1892, ibid., 11:0155-0161; Interview of Maj. T.A. Beaton, March 9, 1892, ibid., 9:0236-0239; Interview of Gen. R.R. Dawes, n.d., ibid., 11:1153-1155; and Interview of Daniel Strawter, n.d., ibid., 11:1152.

[7] Boyd Crumrine, History of Washington County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: H.L. Everts, 1882), 262; Excerpt from Joseph Fulton McFarland, 20th Century History of the City of Washington and Washington County, Pennsylvania (1910), Siebert Papers, 15:0351-0357; Charles L. Blockson, The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania (Jacksonville, NC: Flame International, 1981), 159-161; William J. Switala, The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001), 69-79; Richard J.M. Blackett, “‘…Freedom, or the Martyr’s Grave’: Black Pittsburgh’s Aid to the Fugitive Slave,” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 61 (1978): 117-134; Life, including his escape and struggle for liberty, of Charles A. Garlick (Jefferson, OH: J.A. Howells and Co., 1902), 5-7; Interview of Charles Garlick, August 9, 1892, Siebert Papers, 13:0046-0049; and Amos Jolliffe to Wilbur Siebert, November 17, 1895, ibid., 13:0085-0089. On rescues see Spirit of Liberty, November 6, 1841; Pennsylvania Freeman, June 19, 1845; Louisville Daily Journal, July 25, 1845; and Anti-Slavery Bugle, May 7, 1847.

[8] Coffin, 171-175; Nelson W. Evans and Emmons B. Stivers, A History of Adams County, Ohio from its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time (West Union, OH: E.B. Stivers, 1900), 407-408; and James W. Torrence to Wilbur Siebert, September 22, 1894, Siebert Papers, 9:0059-0062.

[9] “Reminiscences of the UGRR,” Salem, IN, Republican Leader, December 1, 1893; Hagedorn, 148-149; and Philanthropist, December 18, 1838.

[10] Georgetown Democratic Standard, December 31, 1844. This was one of a number of incidents in which freedom seekers and Underground activists were killed by slave catchers. See also Hagedorn, 187-188; Griffler, 35; and Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1857.

[11] Anti-Slavery Bugle, May 7, 1847; and Excerpt from Eber D. Howe, Autobiography and Recollections of a Pioneer Printer (Painesville, OH: 1878), Siebert Papers, 10:0972-0976.

[12] On the Mechanicsburg and Oberlin-Wellington rescues, see Benjamin F. Prince, “The Rescue Case of 1857,” Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 16 (1907): 292-309; and Jacob R. Shipherd, The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue (Boston: John P. Jewett and Co., 1859).

Author Profile

ROBERT H. CHURCHILL is Professor of History at Hillyer College at the University of Hartford where he teaches courses on American History, Global History, and Political Violence. At Brown University Churchill received a B.A. in History and a Masters in teaching; Churchill also holds a Ph.D. in Early American History from Rutgers University. Churchill’s publications include: To Shake Their Guns in the Tyrant’s Face: Libertarian Political Violence and the Origins of the Militia Movement (University of Michigan Press, 2009) and The Underground Railroad and the Geography of Violence in Antebellum America (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

ROBERT H. CHURCHILL is Professor of History at Hillyer College at the University of Hartford where he teaches courses on American History, Global History, and Political Violence. At Brown University Churchill received a B.A. in History and a Masters in teaching; Churchill also holds a Ph.D. in Early American History from Rutgers University. Churchill’s publications include: To Shake Their Guns in the Tyrant’s Face: Libertarian Political Violence and the Origins of the Militia Movement (University of Michigan Press, 2009) and The Underground Railroad and the Geography of Violence in Antebellum America (Cambridge University Press, 2020).