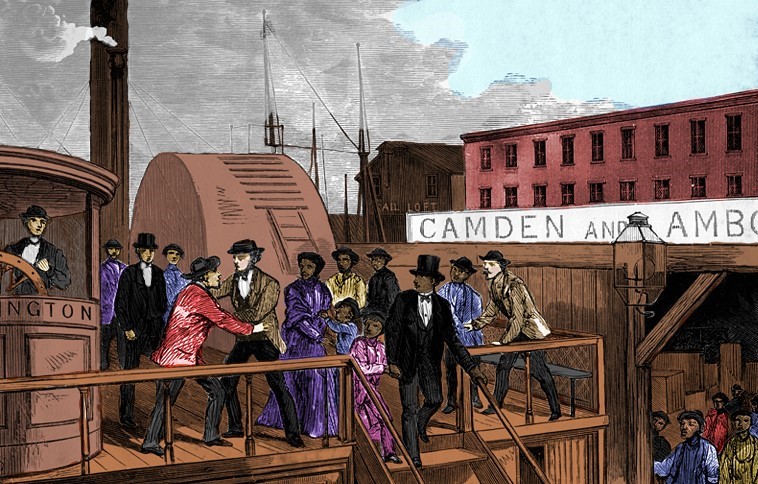

Banner image: In June 1860, slave catchers battled with freedom seekers who were escaping by boat across the Delaware Bay (illustration by John Osler, colorized by Jordan Schucker, House Divided Project)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

Thirty-one-year-old John Atkinson “was a prisoner of hope under James Ray, of Portsmouth, Va., whom he declared to be ‘a worthless sot.’ This character was fully set forth, but the description is too disgusting for record. . . Daily toiling to support his drunken and brutal master, was a hardship that John felt keenly, but was compelled to submit to up to the day of his escape….A part of John’s life he had suffered many abuses from his oppressor, and only a short while before freeing himself, the auction-block was held up before his troubled mind. This caused him to take the first daring step towards Canada, to leave his wife, Mary, without bidding her good-bye, or saying a word to her as to his intention of fleeing.”[1]

In 1854, Atkinson was hidden aboard the steamship City of Richmond that left the Norfolk harbor with the assistance of a free Black steward, John Minkins. Atkinson recalled his departure as particularly painful because in his haste he left without informing his wife, parents, or friends. Shortly after reaching the Philadelphia vigilance committee headed by William Still, he prepared to leave for St. Catharines in Canada West (later Ontario), the home of Harriet Tubman and other freedom seekers. Like many men who were forced to leave their families behind, it is unknown whether Atkinson was ever able to reunite with his wife. What is known is that he escaped during a period when there were so many fugitive departures that local newspapers were warning of “stampedes.” Other immigrants to St. Catharines included Dan Josiah Lockhart who escaped in 1847 from Frederick County, Virginia, William George who left from Harpers Ferry in 1851, Henry Banks who escaped with Isaac Williams from Ayler’s slave pen in Richmond, Virginia in 1854, Christopher Nicholson from Fredericksburg, and David West who arrived in 1854 from King and Queen County.[2]

In 1855, local authorities in Norfolk failed to discover more than twenty freedom seekers aboard the City of Richmond schooner (illustration by Edmund B. Bensell, colorized by Forbes, House Divided Project)

Historian Eric Foner observed that unlike most Underground Railroad operations in the nation, the assisted escapes along the eastern seaboard had clear networks that connected freedom seekers to northern stations. In contrast, further inland freedom seekers were more independent and typically had no one assisting them until they reached the edges of northern states. Once there, the networks of protection and assistance were finally available.[3]

Historian Eric Foner observed that unlike most Underground Railroad operations in the nation, the assisted escapes along the eastern seaboard had clear networks that connected freedom seekers to northern stations. In contrast, further inland freedom seekers were more independent and typically had no one assisting them until they reached the edges of northern states.

Historian David Cecelski, who examined the world of Black watermen along the eastern seaboard in the 1800s, noted that the stories of freedom seekers who escaped via the waterways “reveals a powerful, complex, and dissident undercurrent to maritime life.” Enslaved and free Black watermen, stewards, dockworkers, ferrymen, oystermen, seamen, hotel and tavern workers, skilled artisans, stevedores, and swampers used their jobs to create pathways to freedom for themselves and others.

The distinctive intertwined waterway landscape along the Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay produced a thriving national and international trade system. The Atlantic coastline was where the America’s population concentrated, especially in the port cities and towns. This was also where enslaved African Americans were concentrated until the domestic slave trade distributed an equal number within the interior cotton plantations from the Carolinas to Texas.[4] As early as the late 1600s, newspaper advertisements illustrated the importance of the waterways as the vehicle for freedom seekers along the eastern seaboard. Some traveled to port cities and towns to disappear within the free Black communities there or found refuge in the Great Dismal Swamp or the Everglades.

The principal southern ports that spanned from Jacksonville, Florida, Savannah, Georgia, Charleston, South Carolina, Wilmington, North Carolina, Norfolk, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland to northern cities such as Philadelphia, New York, and Boston were important departure points for the schooners and steamships. In particular, port cities with large African American populations and a robust port activity with ships running between Philadelphia, New York and Boston, were centers of Underground Railroad activity, despite efforts by slaveholders to create a security system to protect their interests. For example, Wilmington, regarded as the “asylum for Runaways” and the Great Dismal Swamp that spanned from North Carolina to Virginia, were hubs of activity, facilitated by the intricate system of rivers and canals that led to the Atlantic Ocean and the Chesapeake Bay. To the north, the Kanawha and Ohio rivers created important waterway routes for freedom seekers as abolitionists assisted often with stations spaced 30 to 40 miles apart. During the 1800s, these vessels transported cotton, tobacco, rice, corn, wheat, pork, naval stores, and other goods and products produced primarily by enslaved labor. These port cities located in low-lying areas connected to extensive river, canal, and marshland systems that went far into the interior where plantations were plentiful.[5]

The topography along the Atlantic Coast, combined with the population density of Blacks along the eastern seaboard and the heavy use of bound labor in the maritime and trade industries, provided enslaved people with unprecedented access to the countless domestic and international vessels that plied its shipping lanes. Most coastal freedom seekers followed the smaller rivers, canals, and creeks to the major Atlantic port areas. And these ports often had a reputation for being either magnets or asylums for runaways. For example, freedom seekers in eastern North Carolina traveled from the Albemarle Sound through the Dismal Swamp to the Norfolk harbor. Others sought escape aboard schooners that plied towns and villages along the smaller rivers.[6]

The topography along the Atlantic Coast, combined with the population density of Blacks along the eastern seaboard and the heavy use of bound labor in the maritime and trade industries, provided enslaved people with unprecedented access to the countless domestic and international vessels that plied its shipping lanes.

The coastal escape routes were well known among local inhabitants, especially in the greater Tidewater region of Virginia that included the areas from Great Dismal Swamp and Norfolk to the Richmond area. While African Americans and some whites created tight circles of cooperation that facilitated escapes, white merchants and slaveholders went to great lengths to tighten security and control, albeit with limited success. Some runaways were able to secure their freedom by hiding aboard vessels and from their captains and crew. Most, however, received assistance from captains and stewards, whose motivations were either financial or ideological.[7]

Nathan and Polly Johnson sheltered Frederick Douglass at their home in New Bedford, Massachusetts after his 1838 escape (NPS)

Historian Kathryn Grover notes in The Fugitive’s Gibraltar (2001) that merchants from New Bedford, Massachusetts frequently traded in Virginia. Some of those merchants were Quakers with strong antislavery leanings, such as Weston Howland and John Parker, owners of the sloop Regulator. Principally transporting flour between Alexandria and New Bedford, the Regulator was associated with assisting runaways from Richmond through Washington, DC. Similarly, the sloop Mercury, owned by Samuel Chadwick, reportedly transported fugitives along with goods between various urban ports in Virginia to Massachusetts throughout the first half of the 1800s. New Bedford was one of the few northern cities that allowed fugitives to receive food and provisions as part of their poor relief program. This was obviously important to freedom seekers as they established themselves in a new community. Despite this support, many of those who escaped to New Bedford and other northern cities, such as Newburyport, Massachusetts, Newport, Rhode Island, and Philadelphia tended to remain under the guise of an alias, primarily because slave catchers were always on the lookout for fugitive slaves.[8]

The work of William Still, who headed the Philadelphia vigilance committee during the 1850s, was invaluable for the coastal operations of the Underground Railroad from the Carolinas to Canada. His documentation of individuals who passed through his Underground Railroad station on their way to freedom from 1852 to 1861, provides a glimpse about activities, organization, and connections along the eastern seaboard where the majority of the nation’s population, both free and enslaved, lived. Still also was central in identifying steamships used by fugitives in their escape. Still recorded the efforts of numerous schooners, captains, and steamships, such as the City of Richmond, the Jamestown, the Pennsylvania, the Augusta, the Kesiah, and the Francis French as being among the primary vessels that plied the intricate system of waterways transporting freedom seekers to points north.[9]

William Still helped coordinate the rescue of Jane Johnson and her children as they passed through Philadelphia in 1855 (illustration from 1872, colorized by Gabe Pinsker, House Divided Project)

While William Still’s invaluable documentation of freedom seekers who passed through his station in Philadelphia continues to yield new clues about this clandestine system, most of the freedom seekers who departed from Georgia and Florida never reached the North. Instead, their destinations were much closer to home: the Bahamas, the Everglades, and Pensacola, Florida. Known as the saltwater railroad, those who escaped from slaveholders in Florida and Georgia sought freedom with the Seminole Indians, in the British-controlled Bahamas, and along the isolated areas around Pensacola whose inhabitants were indifferent to slavery and to enforcing the rights of slaveholders.[10]

After Great Britain’s Colonial Office proclaimed in 1825 that any enslaved Americans who reached the shores of the Bahamas would be considered free, the incentives to escape were clear for freedom seekers who were familiar with the waterways in southern Florida and the Caribbean. Following Britain’s abolition of slavery across the empire in 1834, records indicated that over 6,000 freedom seekers had indeed received freedom in the Bahamas during that period, including many from the United States, angering American slaveholders and their supporters.[11]

Despite the romanticized and overly dramatized versions of the Underground Railroad featuring enslaved fugitives racing along darkened roadways or through forests to freedom, the role of waterways was more dominant and often more successful. Traveling over land was replete with too many obstacles that included a dangerous, crowded roadway system. Traveling aboard ship, however, allowed for a quicker, more direct, and secretive mode of escape.[12] As was the case with John Atkinson, these secretive departures were sudden and often without notification to loved ones. Yet, once the freedom seekers arrived safely in the North, their journey was not over, nor their freedom guaranteed because slavery was legal in the United States, and the law required that the federal government ensure the return of all fugitives.

Escaping from Norfolk in Captain Lee’s skiff in 1857, illustration by Charles H. Reed, colorized by Gabe Pinsker (Smithsonian)

Further Reading

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. New York: Amistad / HarperCollins, 2005.

- Clavin, Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Drew, Benjamin. A North Side View of Slavery: The Refugee. Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856.

- Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W. Norton, 2015.

- Gara, Larry. The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky; Reprint edition, 1996; orig. 1961.

- Grover, Kathryn. Fugitives Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

- Miller, Steve and J. Timothy Allen. Slave Escapes and the Underground Railroad in North Carolina. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016.

- Still, William. The Underground Railroad. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872.

- Walker, Timothy, ed. Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021.

Citations

[1] William Still, The Underground Railroad (orig. pub. 1872; Oxford, UK: Benediction Classics, 2008), 297; Journal C of Station No. 2 of the Underground Railroad, Agent William Still, 1852–1857, Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers, HSP, edited by Peter P. Hinks, 105.

[2] Benjamin Drew, A North Side View of Slavery: The Refugee (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856), 19-30, 43-91; Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad / HarperCollins, 2005), 255; William Still Underground Railroad, 260, 297-300.

[3] Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), 44-47.

[4] 1820 Population Map, US Census Bureau; “Mapping Slavery in the Nineteenth Century,” courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Coast Survey, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference /maps/distribution_of_slaves_in_1860.html, Accessed August 22, 2021.

[5] Timothy Walker, editor, Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), 3-4; Steve Miller and J. Timothy Allen, Slave Escapes and the Underground Railroad in North Carolina (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016), 37, 39, 42.

[6] Timothy Walker, Sailing to Freedom, 57.

[7] Timothy Walker, Sailing to Freedom, 56.

[8] Kathryn Grover, The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 2-3, 8, 10-12.

[9] Fergus Bordewich, Bound for Canaan, 256-257.

[10] Matthew J. Clavin, Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 2, 8; Irvin Winsboro and Joe Knetsch, “Florida Slaves, the ‘Saltwater Railroad,’ the Bahamas, and Anglo-American Diplomacy,” Journal of Southern History 79 (February 2013), 51.

[11] Irvin Winsboro and Joe Knetsch, “Florida Slaves,” 56.

[12] Timothy Walker, Sailing to Freedom, 4.

CASSANDRA L. NEWBY-ALEXANDER is an associate professor of History at Norfolk State University and a dean at its College of Liberal Arts. Newby-Alexander also currently serves on the executive board of Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation Board. Newby-Alexander was the co-chair of the Virginia Commission on African American History Education in the Commonwealth and Historical Commission of the Supreme Court of Virginia. Newby-Alexander received a B.A. in American Government and African American Studies at the University of Virginia and her Ph.D. in American History from the College of William and Mary, where she was a graduate teaching assistant and earned a teaching fellowship. Newby-Alexander is the author of Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad (The History Press, 2017) An African American History of the Civil War in Hampton Roads (Arcadia, 2010).

CASSANDRA L. NEWBY-ALEXANDER is an associate professor of History at Norfolk State University and a dean at its College of Liberal Arts. Newby-Alexander also currently serves on the executive board of Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation Board. Newby-Alexander was the co-chair of the Virginia Commission on African American History Education in the Commonwealth and Historical Commission of the Supreme Court of Virginia. Newby-Alexander received a B.A. in American Government and African American Studies at the University of Virginia and her Ph.D. in American History from the College of William and Mary, where she was a graduate teaching assistant and earned a teaching fellowship. Newby-Alexander is the author of Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad (The History Press, 2017) An African American History of the Civil War in Hampton Roads (Arcadia, 2010).