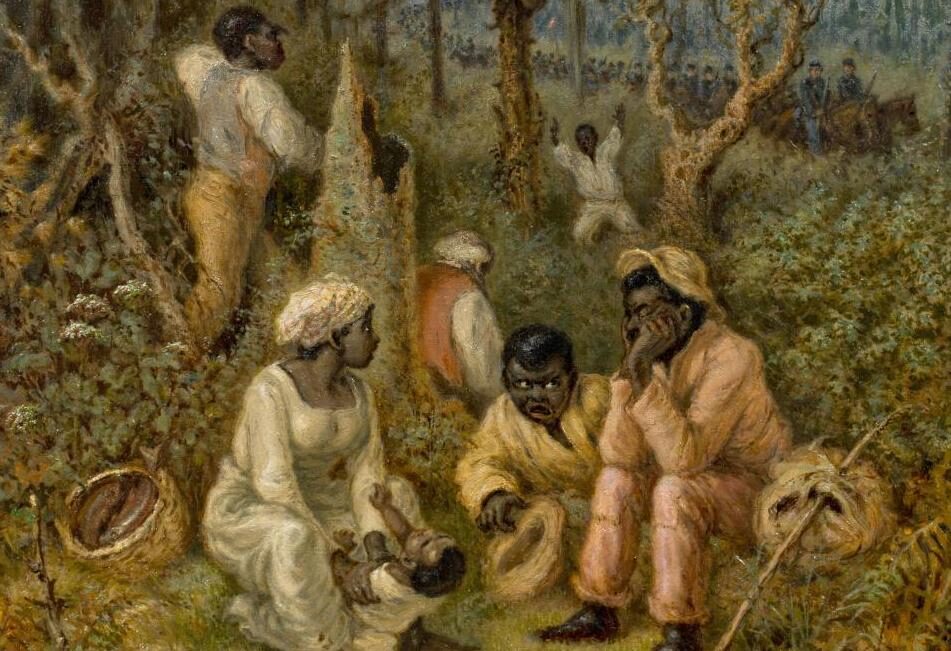

Banner image: Freedom seekers often found refuge in remote southern terrain, as artist and former Union soldier David Edward Cronin depicted in this 1888 painting, “Fugitive Slaves in the Dismal Swamp, Virginia” (NY Historical Society)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

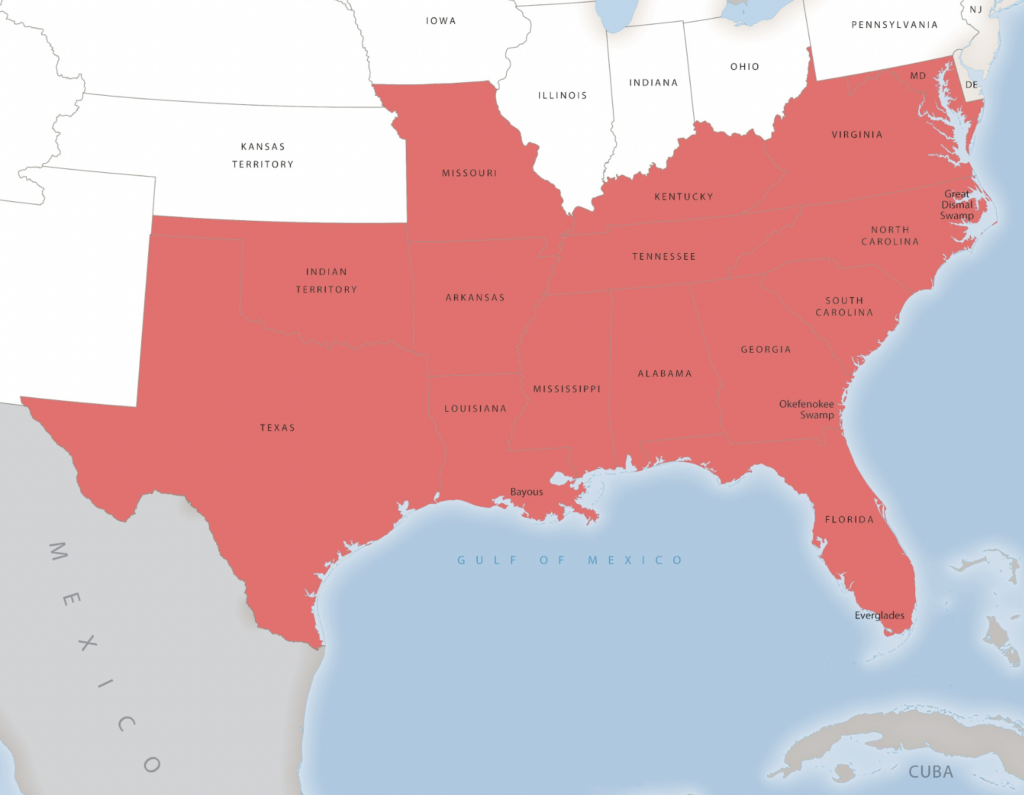

The revolutionary era witnessed major transformations in the geography of slavery and freedom throughout the United States. As the northern states (including the Northwest Territory) either prohibited slavery outright or placed it on the road to extinction through gradual abolition schemes between 1777 and 1804, the southern states witnessed an unprecedented expansion of slavery into the newly acquired territories of the trans-Appalachian South, propelled by the cotton boom of the early 1800s. This development bifurcated the new nation into a “free” North and a “slave” South. The consequences of northern abolition for enslaved people’s opportunities to successfully flee slavery in the antebellum period were far-reaching. Whereas prior to the American Revolution slavery had been legally sanctioned throughout the colonies, in the antebellum period some 100,000 were lured by northern free soil to permanently escape bondage. Freedom seekers indeed helped transform the northern states into sanctuary spaces. As one prominent Massachusetts politician observed in 1837, “every free state is now an asylum for runaway slaves.”[1]

John Thompson escaped from Alabama to Pennsylvania in 1857, hiding aboard railroad cars at night (illustration by Wilbur F. Osler, colorized by Gabe Pinsker, House Divided Project)

Not all African Americans fled northward, however. Indeed, many—if not most—remained within the slaveholding states, despite the existence of free soil elsewhere on the continent. From Baltimore to the Great Dismal Swamp to the Seminole communities of Florida, freedom seekers could be found throughout the slaveholding states, hiding out in a wide variety of social and geographic settings. Generally speaking, slave flight within the antebellum South can be divided into three categories. First, freedom seekers practiced urban marronage, fleeing to towns and cities across the southern states and attempting to pass for free Blacks. Second, they practiced wilderness marronage, seeking refuge in remote settings that provided natural cover (including woods and swamps that lay within the boundaries of plantations). And third, they practiced marronage with sympathetic Native American communities who helped protect them from recapture.

Urban Marronage

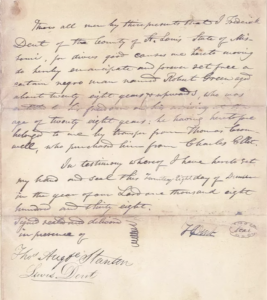

1838 manumission from Missouri (NPS)

In the antebellum period urban marronage quickly became the most widely practiced and popular form of internal slave flight, as any perusal of runaway slave ads makes abundantly clear. Runaways were frequently suspected of “passing for free” in southern towns and cities. Although passing for free was not uncommon in the colonial period, opportunities for successfully doing so were greatly enhanced in the antebellum period due to the dramatic growth of urban free Black populations in the early 1800s. At the same time that the northern states were enacting abolition and embracing a commitment to free soil, the southern states briefly opened the doors to Black freedom by facilitating individual manumission and self-purchase arrangements, especially in the Upper South between 1790 and 1810. By 1810 more than 10 percent of the African American population of the Upper South was classified as free. Even in the Lower South the proportion of free Blacks increased from under 2 percent in 1790 to almost 4 percent by 1810. Many manumitted and self-purchased African Americans gravitated to towns and cities. Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, Charleston, and countless smaller towns across the southern states saw their free black communities considerably augmented in the early decades of the 1800s. By the eve of the Civil War a majority of the African American populations in both Baltimore and the District of Columbia were free. Opportunities for runaways to achieve anonymity and pass for free in the urban South expanded significantly, and untold numbers of freedom seekers therefore headed for towns and cities.

In the antebellum period urban marronage quickly became the most widely practiced and popular form of internal slave flight, as any perusal of runaway slave ads makes abundantly clear.

Two factors in particular motivated some freedom seekers to make for nearby towns and cities within the slaveholding states, rather than free soil states and territories beyond the South. First, enslaved people’s social and occupational networks often lured and led them to urban areas. Runaway slave advertisements in southern newspapers as well as antebellum court records reveal that runaways within the South usually had free Black contacts in urban areas who could provide them with vital assistance and information. These included family, friends, friends of friends, or acquaintances made during a hiring stint or while running an errand for the master in town. Second, and just as important, was the fact that flight to southern towns and cities provided freedom seekers with opportunities to flee slavery without severing all ties with loved ones. Fleeing beyond the borders of the antebellum South might have provided runaways with a safer and more legitimate claim to freedom, but it also had the major disadvantage of separating refugees from their homes and families—potentially forever. For many freedom seekers, even those who lived within relatively easy reach of free soil, state and international borders seemed like a door of no return that they were unwilling to pass through if they could avoid it.

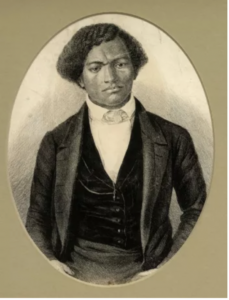

Frederick Douglass used a forged pass in making his escape from Baltimore in 1838 (NPS)

Passing for free in the urban South entailed a fair bit of theater. It entailed looking and acting free and erasing visible markers that gave one away as an enslaved person. Freedom seekers employed a wide variety of strategies to disguise their slave status. Their first order of business was usually to exchange the uncomfortable and drab garb accorded to country slaves and acquire the more fanciful clothing worn by urban free Blacks. Second, they became fully integrated within free Black communities, “disappearing” in free Black neighborhoods, free Black homes and boarding houses, free Black churches, and free Black places of business. Third, they hired their labor as if they were free Blacks, performing all manner of both skilled and unskilled jobs that tended to be dominated by urban African Americans. Men especially worked about the wharves, as stevedores and dockworkers, but also in construction and other day-labor services. Women usually worked as washerwomen, domestics, and in the markets. Fourth, and most importantly, they acquired false papers to “prove” that they were free, should any suspicious person demand to see them. A black market in forged passes and forged freedom certificates thrived throughout the urban South, providing opportunities for crafty freedom seekers to stay at large indefinitely.

Wilderness Marronage

“Living in a hollow tree,” from William Still, Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Gabe Pinsker (House Divided Project)

Although most southern freedom seekers practiced urban marronage in the antebellum period, others practiced various forms of wilderness marronage. Two forms in particular can be distinguished. First, bands of freedom seekers formed small communities in remote and desolate areas, largely detached from plantation society. Unlike urban maroons, wilderness maroons lived in “survival” conditions, with only the most basic self-made shelters and subsisting on what they could hunt and scavenge. Occasionally they were known to emerge from the woodlands to plunder plantations for food and supplies. Cases of runaway slaves “lurking in swamps, woods and other obscure places, killing hogs and committing other injuries to the inhabitants of the Territory” of antebellum Florida were common enough that in 1828 the territorial legislature enacted a law to regulate their recapture by ordinary white civilians. Bands of runaways in the lowcountry swamps of South Carolina in the 1820s caused such “alarm and danger” to local plantation owners that they petitioned the state legislature for military assistance, convinced that the maroons were preparing to launch an insurrection.[2] Certain regions were known as popular hideaways for wilderness maroons because they were difficult to traverse by slave catchers and militias. Swamplands in particular—most notably those in the South Carolina and Georgia lowcountry, southern Louisiana, and especially the Great Dismal Swamp on the border between Virginia and North Carolina—were common destinations for freedom seekers.

Second, individual freedom seekers became “borderland maroons.” Most wilderness maroons indeed did not seek freedom in remote areas, but rather settled in the wooded borderlands of plantations and farms. Unlike their more isolated counterparts, borderland maroons retained contact with loved ones who remained in bondage and who constituted a vital lifeline in their bids to achieve freedom from slavery. Borderland maroons were known to remain at large for years, living in makeshift shelters, “lurking” about forests and swamps, “sleeping out” in warm weather and sometimes taking shelter in outbuildings or even family members’ cellars or attics in the winter. For food and information regarding potential recapture, they relied heavily upon their loved ones in the slave quarters.

Native American Marronage

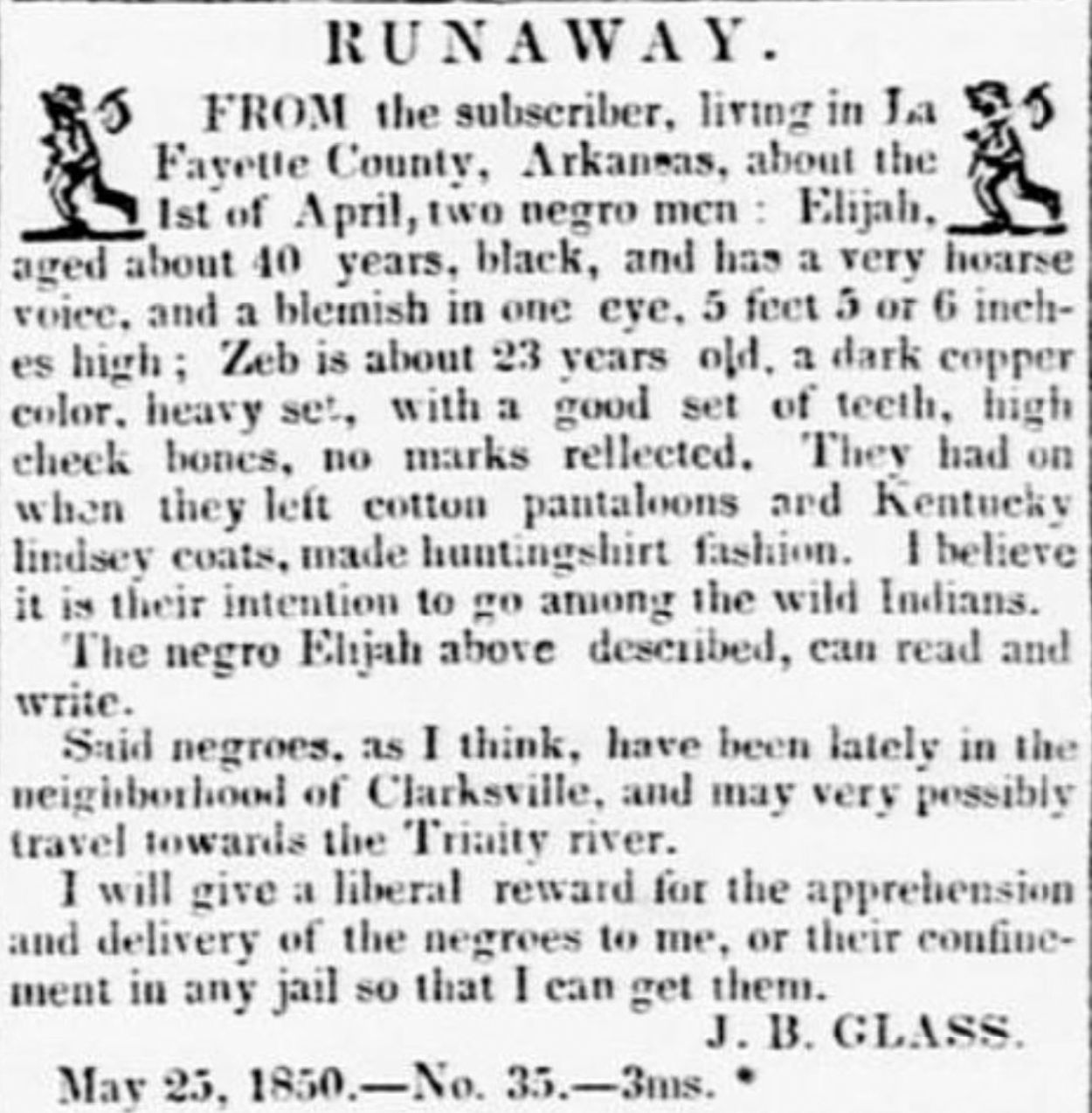

Finally, antebellum southern freedom seekers sought refuge with sympathetic Native American communities, who protected them from recapture and reenslavement. This strategy of escape also originated in the colonial period when many indigenous communities all along the Atlantic seaboard accepted runaways in their ongoing struggles with European colonial authorities. South Carolina slaves fled westward into enemy Indian country in 1735 and were “sheltered & protected by the Tuskerora Indians,” a situation that so infuriated the colonial Assembly that it offered a bounty to freemen or slaves who killed or captured any members of that nation.[3] In colonial Georgia, 20 runaway slaves advertised between 1763 and 1775 were headed for indigenous communities in the backcountry. However, protection for fugitives was not always forthcoming, and many Native American communities were known to return runaway slaves to the English or even kill them.

In the antebellum period, the devastating effects of war, colonization, removal, and westward expansion greatly diminished opportunities for marronage with indigenous communities, but there were exceptions. The Black Seminoles of northern Florida constituted the most well-known and long-lasting (though certainly not the only) of such communities. The Black Seminoles originated in the late 1600s and early 1700s, when Spanish Florida promised asylum and protection to runaway Africans from rival English settlements in the Carolina lowcountry. Spanish authorities demanded a conversion to Catholicism and military service along the border near St. Augustine. In practice, many freedom seekers evaded such demands by seeking refuge with indigenous communities who were also fleeing into the borderlands of Florida—mostly Creek but also Choctaw and Appalachicola. Over time, these blended Native peoples came to form a distinct community called the Seminole. African freedom seekers were granted sanctuary by Seminole leaders and allowed to cultivate their own land in return for paying annual tributes (in the form of crops and game) and participating in armed conflicts when they arose. The system benefitted both parties—Africans gained freedom and protection from reenslavement, and the Seminoles gained important allies in the constant colonial threats to their communities.

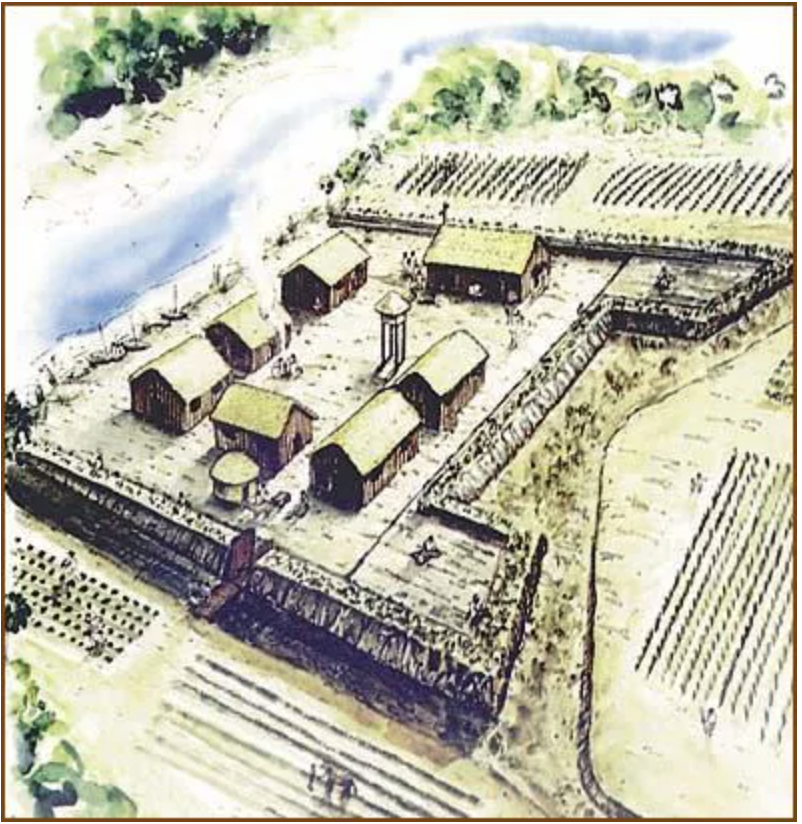

The historic site that was Fort Mose near St. Augustine is part of the NPS Network to Freedom (NPS)

The Black Seminole maroon settlements were continually augmented by new waves of freedom seekers, including during and after the American Revolution. Each generation vigorously defended its settlements against slave catchers and US army incursions. In the early years of the republic the Seminole maroon communities caused lawmakers serious concerns, especially when they supported the British in the War of 1812. The United States waged two wars against the Seminole in the antebellum period, the first in 1817-1818 and the second in 1835-1842 (during attempts to forcibly remove much of the community to Indian Territory). After the first war, many Black Seminoles began to move farther into central and south Florida, and beyond to the Bahamas, and by the 1840s many had been forcibly removed west.

The Black Seminole maroon settlements were continually augmented by new waves of freedom seekers, including during and after the American Revolution. Each generation vigorously defended its settlements against slave catchers and US army incursions.

The widespread existence of maroon communities within the slaveholding states illuminates the complicated geography of freedom that existed in North America in the decades preceding the US Civil War. For enslaved people seeking to flee bondage in the antebellum South, freedom could be found in virtually every direction and in a wide variety of geographical, political, and social settings, reminding us that beacons of freedom were not limited to “free soil.”

An 1850 runaway ad described freedom seekers intending “to go among the wild Indians” (Texas Runaway Slave Project)

Further Reading

- Franklin, John Hope and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Diouf, Sylviane. Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

- Pargas, Damian Alan, ed. Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018.

- Rivers, Larry Eugene. Runaways and Rebels: Slave Resistance in Nineteenth-Century Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013.

- Clavin, Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Citations

[1] Henry B. Stanton, Remarks of Henry B. Stanton, in the Representatives’ Hall, on the 23nd (sic) and 24th of February, Before the Committee of the House of Representatives, of Massachusetts, to Whom was Referred Sundry Memorials on the Subject of Slavery (Boston: I. Knapp, 1837), 62.

[2] “An act related to crimes and misdemeanors committed by slaves, free negroes and mulattoes,” in Acts of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida, Passed at Their Seventh Session (Tallahassee: William Wilson, 1828), 174-190; Petition of Inhabitants of Clarendon, Clarmont, St. James, St. Stephens, and Richland districts to the Senate of South Carolina, ca. 1824, reprinted in John Hope Franklin & Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 303-306.

[3] Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W.W. Norton, 1974), 260.

Author Profile

DAMIAN ALAN PARGAS is the Professor of History and Culture of North America at Leiden University in the Netherlands and executive director of the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies in Middelburg. Pargas studied social history at Leiden University, receiving his MA and PhD. Pargas has written two books and several articles on American slavery, slave family-life, and slave migration in the 19th century. From 2011-2014 Pargas worked in a Veni postdoctoral fellowship from the Dutch Council for Scientific Research (NWO) for his project “Newcomers in Chains: Slave Migrants in the Antebellum South, 1820-1865.” Additionally, Pargas is a board member of the Netherlands American Studies Association as well as founder and chief editor of the Journal of American History. Pargas supervises the NOW project “Newcomers in Chains: Slave Migrants in the Antebellum South, 1820-1865.”

DAMIAN ALAN PARGAS is the Professor of History and Culture of North America at Leiden University in the Netherlands and executive director of the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies in Middelburg. Pargas studied social history at Leiden University, receiving his MA and PhD. Pargas has written two books and several articles on American slavery, slave family-life, and slave migration in the 19th century. From 2011-2014 Pargas worked in a Veni postdoctoral fellowship from the Dutch Council for Scientific Research (NWO) for his project “Newcomers in Chains: Slave Migrants in the Antebellum South, 1820-1865.” Additionally, Pargas is a board member of the Netherlands American Studies Association as well as founder and chief editor of the Journal of American History. Pargas supervises the NOW project “Newcomers in Chains: Slave Migrants in the Antebellum South, 1820-1865.”