Banner image: Many freedom seekers in search of greater security chose to settle in Canada West, depicted in this 1857 map, where slaveholders had no legal recourse to recapture them (House Divided Project)

Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

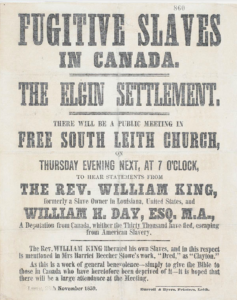

1859 anti-slavery broadside from Canada West (Library and Archives Canada)

From the late 1700s until shots rang out in Charleston Harbor before dawn on April 12, 1861, Canada, particularly Ontario, then known as Canada West or Upper Canada, stood as a beacon of freedom to enslaved Blacks. In 1856, abolitionist Benjamin Drew called the area a “Refuge for the Oppressed” and stressed that it had become a destination for thousands who followed the North Star.[1] The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada reported that the Underground Railroad fueled the growth of Ontario’s Black population, from about 500 in 1791 to some 30,000 persons in 1852. After Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, free Blacks who feared kidnapping and resented Black Codes adopted by most northern states joined increasing numbers of enslaved persons seeking safety in the northern dominion. The magnitude of this migration, which scholars continue to study and debate, suggests that early Ontario was more than just an Underground Railroad terminus or a scattering of safe houses on a strange landscape where activists sheltered freedom seekers. Rather, the Underground Railroad in Canada West represented a remarkable community of Blacks and whites—men and women who exercised agency in myriad ways to advance the cause of freedom. Working together, and with others in the United States and Britain, they established institutions and framed legislation that confirmed Canada as a place of formal freedom, a safe haven for those fleeing slavery and a bastion from where militants could challenge the hateful institution and check its reach above the Mason-Dixon Line. This biracial coalition’s advocacy, determination, transnational relationships, and initiatives ensured that Canada West remained a sanctuary for freedom seekers. These men and women expelled slave catchers and kidnappers; journeyed to the South to rescue enslaved persons; lobbied legislators in Canada and London to protect the freedom of all residents; petitioned the Queen and her representatives in the name of higher law; and finally, after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, they mobilized to wage a war of liberation.

The origins of this [Canadian] antislavery community can be traced to the escape, recapture, and resistance of James Somerset, an enslaved Black man whose owner took him to England and then sought to return him to slavery in the Americas.

The origins of this antislavery community can be traced to the escape, recapture, and resistance of James Somerset, an enslaved Black man whose owner took him to England and then sought to return him to slavery in the Americas. Somerset’s freedom fight caught the attention of London abolitionists, such as Granville Sharp who brought his case before the Court of the King’s Bench. In 1772, Chief Justice Lord Mansfield ruled that slavery was “so odious” it could not be allowed unless it was sanctioned by positive law.[2] Finding no statute or judicial precedent supporting slavery in England, Mansfield declared Somerset free and stated that he could not be forcibly returned to slavery, establishing the free-soil principle in England. Sharp, William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Olaudah Equiano and other abolitionists demanded that the free-soil principle be applied to Britain’s American possessions. Responding to an antislavery groundswell in early Ontario ignited by the sale of an enslaved woman named Chloe Cooley, John Graves Simcoe, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada and a friend of Wilberforce, sought to do just that in 1793. When Peter Martin, a prominent Niagara Black man who along with other bystanders had witnessed Cooley’s desperate resistance as an American slaveholder forced her on a boat, petitioned the province’s Executive Council. Simcoe seized the opportunity to push An Act to Limit Slavery through the colonial legislature despite resistance from several slaveholders on his council.[3] Although the resulting gradual abolition law freed only enslaved children when they reached the age of 25, it also prohibited the importation of enslaved people, thus rescinding King George III’s Imperial Act of 1790 that had been designed to protect Loyalist slaveholders’ rights to human property after they moved to Canada. Simcoe’s act served as the death knell for Canadian slavery, since it effectively freed any slaves arriving from other countries. Soon after it came into effect, court decisions in neighboring Lower Canada, the province of Quebec, rendered slavery untenable there as well.

Canadian emancipator, John Graves Simcoe (Archives of Ontario)

News of the emerging sanctuary in Britain’s northern possession traveled quickly through Black communities in the United States, enhancing Canada’s appeal and sparking the first major wave of African Americans following the North Star across the border. Migration gained momentum after 1807 when Britain banned the transatlantic slave trade, and the Royal Navy began intercepting slaving vessels on the high seas. In 1819, embracing the Somerset free-soil principle, Upper Canada’s Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson, responding to American demands to extradite fugitives from slavery, informed Washington that the northern dominion had “adopted the Law of England.”[4] Robinson emphasized that regardless of what had been the status of freedom seekers prior to arriving in Canada, when they set foot on Canadian soil, they were forever free. This extradition refusal, coupled with news of Britain’s recognition of the valor of Black Canadians serving in the War of 1812, including granting them homesteads in Oro Township, further enhanced Canada West’s appeal for Black Americans.

In the 1820s, Ontario’s attractiveness also benefited from a new strand of British abolitionism rooted in both the Bible and the law. In the pamphlet Immediate, Not Gradual Emancipation (1824), Elizabeth Heyrick, an outspoken English Quaker and leading abolitionist, declared that slaveholders had no right to interpose themselves between the Creator and His earthly beings, and she branded slavery “a sin to be forsaken immediately.”[5] Writing from London in 1828, Lord Aberdeen staunchly rejected renewed American demands for the extradition of fugitive slaves, telling the United States ambassador to Britain Albert Gallatin that “the law of Parliament gave freedom to every slave who effected his landing upon British ground.”[6]

African Americans reacted—in print and by traveling to Britain’s northern dominion in increasing numbers. In The Appeal, in Four Articles (1830), the radical Black abolitionist David Walker concluded the British were now “the best friends the coloured people have.”[7] With cotton plantations spreading across the American South and Black Laws sweeping the free states, Britain’s northern dominion was even more inviting—particularly as growing numbers of Black residents built vibrant, welcoming communities. After the 1829 Cincinnati race riot, 32 families moved near London, Ontario, to establish an all-Black settlement, which they named Wilberforce. It soon had substantial livestock, pigs, horses, a grist mill, a sawmill, a school, and two churches. Further, Sir John Colborne, Upper Canada’s new lieutenant governor, began to openly welcome Black residents. In a letter to James C. Brown, a leading Black Ohioan, he stressed the difference between Canada and the United States. “Tell the Republicans on your side of the line,” wrote Colborne, “we do not know men by their colour. If you come to us, you will be entitled to all the privileges of the rest of His Majesty’s subjects.”[8] Colborne’s message rang true in 1833 when he refused to extradite Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, two fugitives from Kentucky slavery who were rescued in Detroit and spirited across the river to Windsor. That same year the Imperial Parliament passed the Emancipation Bill abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire, effective August 1, 1834.

British abolition initiated another wave of migration that further strengthened Black communities in Canada. The burgeoning Black population established churches, benevolent societies including 14 chapters of the famous True Band Society, the legendary Canadian Black militia known as the Coloured Corps, as well as schools, farms, and businesses. The increasing number of Blacks fueled Canada West’s antislavery militancy. In 1835, Canadian Blacks pursued slave catchers across the border after they had kidnapped the Stanford family in St. Catharines. The Canadians rescued the Black family in a pitched battle near Buffalo that the African American novelist William Wells Brown dubbed “one of the most fearful fights for freedom.”[9] The militants returned the Stanfords to St. Catharines and demanded authorities indict two Canadians who participated in the kidnapping. In 1837, when a sheriff jailed a freedom seeker named Solomon Moseby for having stolen a Kentucky slaveholder’s horse for an escape to Canada, about two hundred Niagara Black men, supported by their wives and white neighbors, rescued him, signaling to American slaveholders that fugitive slave renditions would not be tolerated north of the border. Later that same year, the case of Jesse Happy, another Kentucky freedom seeker who had also escaped with his owner’s horse but left it at the border so that he would not be charged as a felon, saw British officials confirm their stance on extradition. They responded to American demands for Happy’s extradition by declaring that individuals would only be extradited if they committed acts that were crimes in Canada; the officials noted that flight from slavery was not a crime since slavery was illegal in the northern dominion.

Against this background, The Colored American celebrated Canada as “salubrious and fertile as any other country under the sun” and forecast that “hundreds of thousands of our brethren” would soon find sanctuary there.

Against this background, The Colored American celebrated Canada as “salubrious and fertile as any other country under the sun” and forecast that “hundreds of thousands of our brethren” would soon find sanctuary there.[10] When in 1841 Britain curtly rejected American extradition demands to return Blacks who revolted on the slave ship Creole, murdering crew members and commandeering the vessel to the Bahamas, the newspaper’s prediction seemed sound. London officials indicated that the alleged mutineers and murderers acted only “to obtain their Freedom” and stressed that because British law recognized natural rights to freedom, self-theft represented defense of the right to liberty. When Lord Ashburton met Secretary of State Daniel Webster later in the year to negotiate the agreement that became the Treaty of Washington of 1842, the British cabinet instructed him to “repudiate any proposal to surrender up a person charged with the mere offence of escaping from Slavery.”[11]

Britain’s diplomatic stance set the stage for additional Black settlements in Canada—Queen’s Bush, the Dawn Settlement that included the manual school known as the British-American Institute, the Refugee Home Society near Windsor, and the Elgin Association in Raleigh Township, the home of the famous Buxton Mission School. Along with Black churches, the Buxton Mission School became central to Black institutional life in the northern dominion, and it produced a generation of remarkable Black Canadian leaders. Renewed African American migration also increased the vibrancy of Black communities in such urban centers as Toronto, Hamilton, and St. Catharines. In 1841, some 12,500 Blacks made Toronto their home. By mid-century, Canadian Black communities were benefiting from truly outstanding leadership—men and women with energy, vision, a wide range of skills, good relationships with antislavery Canadian whites, and ties to transnational antislavery networks in Britain, Europe, and America, including Underground Railroad operatives in such urban centers as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Syracuse, Rochester, Sandusky, Ripley, Cincinnati, Oberlin, Detroit, and Chicago. These Canadian leaders collaborated with the likes of Lewis Hayden, Theodore Parker, Stephen Foster, and Abby Kelley in Massachusetts, Thomas Garrett and William Still in the mid-Atlantic states, David Ruggles, Samuel May, and Frederick Douglass in New York, George DeBaptiste in Michigan, John Anthony Copeland, John Rankin, and Levi Coffin in Ohio, Elijah Anderson in Indiana, and the famous Underground Railroad activist known as Charley in Chicago, Illinois.

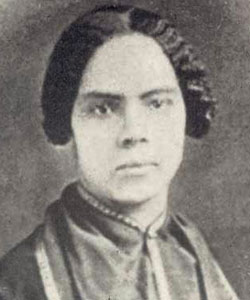

Mary Ann Shadd, “one of Canada’s greatest Black teachers and editors” House Divided Project)

Some Canadian leaders, such as Harriet Tubman and Madison Washington of the Creole revolt, had escaped slavery and risked everything returning from Canada to the South to rescue enslaved family members and friends. Tubman established the Salem Chapel of the St. Catharines British Methodist Episcopal Church as a refuge for hundreds fleeing slavery. Other notable Canadian Blacks who had endured slavery included Alexander Hemsley, Josiah Henson, Anthony Burns, Jermain Wesley Loguen, Henry Bibb, and Samuel Ringgold Ward. They too provided leadership, worked tirelessly in their adopted communities, and became instrumental in the transnational antislavery movement. Some stirred audiences as they spoke on both sides of the Canada-United States border; others advocated in print. During his exile to Canada after the 1851 Jerry Rescue in Syracuse, Jermain Loguen penned his famous antislavery letter to New York governor Washington Hunt. In his final years, Anthony Burns (who had once been captured in Boston in 1854) ministered to a St. Catharines Zion Baptist congregation that included many formerly enslaved persons. He also revealed his radical abolitionism when he wrote to The Liberator declaring that if kidnappers tried to re-enslave him, he would enforce Patrick Henry’s motto “Liberty or Death.”[12] Henry Bibb promoted the Canadian Canaan in his newspaper The Voice of the Fugitive.[13] Samuel Ringgold Ward collaborated with the legendary Canadian Black editor Mary Ann Shadd, making The Provincial Freeman a mouthpiece for Blacks on both sides of the border.[14] Shadd, still regarded today as one of Canada’s greatest Black teachers and editors, relentlessly rallied antislavery militants, voicing powerful opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and US Supreme Court chief justice Roger Taney’s majority opinion in the Dred Scott case in 1857. Shadd employed Osborne P. Anderson, the Black Canadian who survived the 1859 Harpers Ferry Raid. She had likely introduced him to John Brown in Chatham, Ontario and later edited Anderson’s account of the attack on the federal arsenal. She became one of the most effective recruiting officers for the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Salem Chapel in St. Catherine’s, Harriet Tubman’s church (Wikipedia)

Some Canadian Black community leaders had been born free in America but moved across the border seeking safety from kidnappers or refuge from Black Laws. They too became key operatives in transnational antislavery networks and assisted freedom seekers arriving in Canada West. The Rev. William M. Mitchell served a Baptist congregation in Toronto while maintaining ties with Underground Railroad activists in the Ohio country where he had lived; he also collaborated with William Still in Philadelphia. The Rev. William Troy moved to the Canadian side of the Detroit River, where he established Windsor’s First Baptist Church. He welcomed freedom seekers into his congregation, helped them settle on Canadian soil, and later published many of their narratives.[15]

Some Canadian Black community leaders had been born free in America but moved across the border seeking safety from kidnappers or refuge from Black Laws.

Black community leaders joined forces with such antislavery whites as the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada president Michael Willis, Globe and Mail newspaper publisher George Brown, noted politician William Hamilton Merritt, the Lane Seminary rebel and educator Hiram Wilson, Elgin Association founder Reverend William King, the Belleville botanist Dr. Alexander Ross who led rescue missions to the American South, and Laura Haviland, who, after moving to Michigan, guided hundreds of freedom-seekers to her native Ontario. As they challenged slavery south of the border, together they also sought to halt race prejudice in Canada West.

From the outbreak of the American Civil War until Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, members of the biracial coalition that represented the Underground Railroad in Canada West turned their gaze southward. After January 1, 1863, they rallied for the Union in what the outstanding Black Canadian doctor Anderson Ruffin Abbott so aptly called “a war for humanity.”[16] Some 2,500 Black Canadians put their lives on the line in the struggle, including Canada West’s distinguished Black doctors schooled at Buxton and Toronto—Alexander Thomas Augusta, John H. Rapier, Jerome Riley, Martin Delany, and Anderson Ruffin Abbott. They joined Harriet Tubman, Mary Ann Shadd, William Troy, and other remarkable Blacks, taking much-needed resources, skills, determination, courage, and vision southward to support the United States and later meet the challenges of Reconstruction.

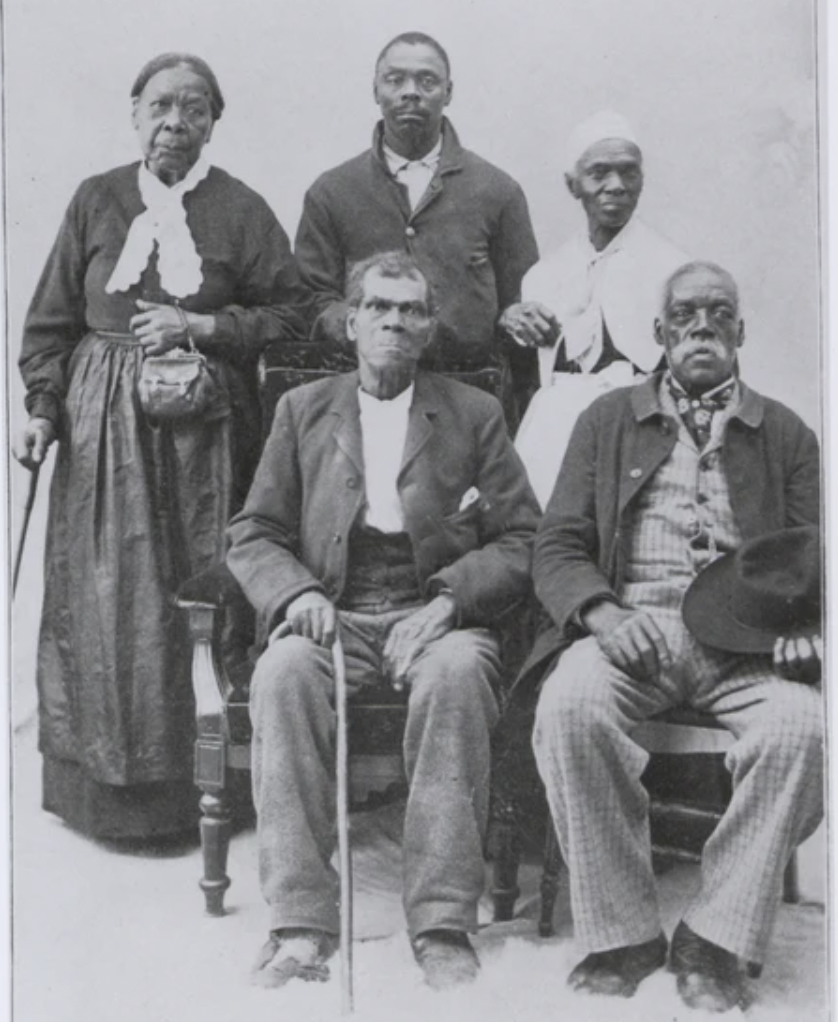

Black Canadians who had been refugees from American slavery, gathering in Windsor, Ontario (formerly Canada West) during the 1890s (From Wilbur Siebert, The Underground Railroad (1898), p. 190)

Further Reading

- Barker, Gordon S. Fugitive Slaves and the Unfinished American Revolution, Eight Cases, 1848-1856. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishers, 2013.

- Brown-Kubisch, Linda. The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black Pioneers, 1839-1865. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2004.

- Smardz Frost, Karolyn. I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land: A Lost Tale of the Underground Railroad. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

- Smardz Frost, Karolyn and Veta Smith Tucker, eds. A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance, and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2016.

- Mackey, Frank. Done with Slavery: The Black Fact in Montreal 1760-1840. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010.

- Damian Alan Pargas, Freedom Seekers: Fugitive Slaves in North America, 1800-1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Reid, Richard . African Canadians in Union Blue: Volunteering for the Cause in the Civil War. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2014.

- Robbins, Arlie C. Legacy to Buxton. North Buxton, Ontario: A. C. Robbins, 2013.

- Winks, Robin W. The Blacks in Canada: A History. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997.

Citations

[1] Benjamin Drew, The North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856), 39.

[2] https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/docs/state_trials.htm

[3] An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for

Servitude, Statutes of Upper Canada Cap. 7, 33 George III, 1793.

[4] William Renwick Riddell, “The Fugitive Slave in Upper Canada,” Journal of Negro History 5, no. 3 (July 1920): 344.

[5] Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition (orig. pub. 1824; Philadelphia: Philadelphia A.S. Society, 1837), 3.

[6] Samuel Gridley Howe, The Refugees from Slavery in Canada West. Report to the Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission (Boston: Wright & Potters, printers, 1864), 14. See also Niles’ Register, (December 27, 1828), 290.

[7] David Walker, Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly to Those of the United States (Boston: David Walker, 1830), 47.

[8] Quoted in Gary E. French, Men of Colour: An Historical Account of the Black Settlement on Wilberforce Street in Oro Township, Simcoe County, Ontario, 1819-1949 (Orillia, Ontario: Dyment-Stubley Printers, 1978), 21.

[9] St. Catharines’ British American Journal, July 23, 1835.

[10] Colored American, January 22, 1839.

[11] Alexander L. Murray, “The Extradition of Fugitive Slaves from Canada: A Re-evaluation,” Canadian Historical Review 43 (1962), 304-306.

[12] The Liberator, August 13, 1858.

[13] Henry Bibb, ed., Voice of the Fugitive (Sandwich, Canada West: Henry Bibb, 1851-1852).

[14] Mary Ann Shadd and Samuel Ringgold Ward, eds., The Provincial Freeman (Windsor, Toronto, Chatham, 1853-1857).

[15] William Troy, Hair-Breadth Escapes from Slavery to Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000)

[16] Anderson Ruffin Abbott Papers, Anderson Ruffin Abbott Collection, Toronto Reference Library; See also Richard Reid, African Canadians in Union Blue: Volunteering for the Cause in the Civil War (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2014), 207.

Author Profile

GORDON S. BARKERis a full professor of history at Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke , Quebec, Canada, where he specializes in African American, Revolutionary America, and Civil War Era history. He received undergraduate degrees in Economics and History from McGill University and his MA and PhD from the College of William and Mary. His works have appeared in leading scholarly journals such as the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography and the American Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties. He has authored two major books called Fugitive Slaves and the Unfinished American Revolution: Eight Cases, 1848-1856 (McFarland, 2013) and The Imperfect Revolution: Anthony Burns and the Landscape of Race in Antebellum America (The Kent State University Press, 2010) as well as several book chapters in edited volumes.

GORDON S. BARKERis a full professor of history at Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke , Quebec, Canada, where he specializes in African American, Revolutionary America, and Civil War Era history. He received undergraduate degrees in Economics and History from McGill University and his MA and PhD from the College of William and Mary. His works have appeared in leading scholarly journals such as the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography and the American Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties. He has authored two major books called Fugitive Slaves and the Unfinished American Revolution: Eight Cases, 1848-1856 (McFarland, 2013) and The Imperfect Revolution: Anthony Burns and the Landscape of Race in Antebellum America (The Kent State University Press, 2010) as well as several book chapters in edited volumes.