Banner image: Crossing the Potomac River at night in 1856; original illustration by Charles H. Reed for William Still’s Underground Railroad (1872), colorized by Gabe Pinsker (National Portrait Gallery)

- Download PDF version of this essay (coming soon)

- See related Timeline entries

Writing on the eve of the Civil War, it was clear to a Cleveland editor that, in running away, the enslaved were the driving force behind the Underground Railroad. The observation calls on us to place at the center of this politically charged movement the enslaved themselves and the decisions they made to leave. Their actions are the mortar holding together the mosaic that is the Underground Railroad.

Why did the enslaved leave the places and family they knew for the uncertainty of new lives among strangers? Did they act on their own initiative? Were they assisted by family and friends? Were they enticed to leave by outsiders? By their actions, the enslaved tell us much about what they thought of freedom. Not surprisingly, they did not have things their own way. Slaveholders acted to recover lost property and to stymie what, by the late 1840s, they considered an “epidemic of runaways.” They formed associations to protect their interests and pressured state legislatures to pass laws to stem the flow of escapes. A proliferation of police forces kept an eye out for escapees. Local struggles had wider political significance as they came to dominate state politics. Those clashes gained national significance once the escapees made it to free soil and slaveholders attempted to retake them.

Stanley Harrold’s Border War (2010) (UNC Press)

As Stanley Harrold shows, cross-border clashes were a feature of relations between Upper South and Lower North states going back to the early 1800s brought about by the actions of the enslaved and the determination of slaveholders to reclaim their property. There were, he posits, “cultural boundaries” between the two sections that influenced the ways the sectors reacted to the unfolding fugitive slave crisis. Robert Churchill agrees, although he divides the Lower North into three distinct regions: the border region, what he calls the “contested region” (running through the middle of the northern states), and finally, the free soil region farther north, each exhibiting what he describes as a “distinct culture of violence” in its reactions to the clash over escaping slaves. Both Harrold and Churchill provide us with a template for examining those pieces of the mosaic that paint a picture of what occurred on the northern front of the Underground Railroad. We need to know more about the nature of those “cultures.” One other feature of the movement needs to be addressed: northerners who went south, as slaveholders believed, to entice the enslaved to abscond. Their actions attempted to beard the lion in his den. They were rarely successful, but they provided proof, if slaveholders needed confirmation, that their property was under direct assault. These abolitionist emissaries, South Carolina argued on the eve of leaving the Union in 1860, persuaded “thousands of …slaves” to abandon “their homes.” Those who left were “incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.” The citizens of the South, one Georgian observed, had been “deprived of their property” and for attempting to seek redress, as promised by law, had sometimes even “lost their liberty and their lives.” [1]

The best way to understand the nature of the conflict between escapees and the system they threatened to undermine is to tell the stories of those who defied all odds to attain their freedom. Doing so requires us to understand what drove others to assist them as well as those who worked to undermine their search for freedom. Admittedly, not all those who left headed to free soil. Many of the 500,000 that John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger estimate left plantations in the late antebellum period sought refuge in cities and towns in the South. A number of recent studies suggest these were not mere truants seeking a temporary respite but were determined to forge a new life of freedom among urban Black and working-class white populations in the area. Admittedly, it is much more difficult to tease out the nature of that assistance. It is clear, however, by evidence drawn from court cases, that many managed to carve out spaces of freedom in the urban South. Much more work needs to be done in order to get a fuller picture of these urban sanctuaries. [2] Whatever their destinations, the stories of their escapes provide us with a valuable mechanism for understanding what drove the enslaved to seek freedom.

The best way to understand the nature of the conflict between escapees and the system they threatened to undermine is to tell the stories of those who defied all odds to attain their freedom.

Here are some stories by way of example. When Henry Banks left Front Royal in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley in February 1853, he was following in the footsteps of many who had decided, largely on their own initiative, to break the bonds of slavery. There is some suggestion that family and friends assisted Banks. He might have been following a known line of escape. In a series of letters sent back to Front Royal, Banks tried to throw fugitive slave hunters off his trail. In spite of what he wrote, those who wished to recapture him knew he was heading for the African American community in Philadelphia, a place, one slave catcher lamented, that contained many “receptacles for fugitives” which made it difficult to retake them. It was, the slave catcher claimed, like “looking for a needle in a haystack.” It appears that members of Philadelphia’s Black community protected Banks. The presence of the slave catcher, however, must have unnerved him. Within days, he was on the move again, this time to a community of manumitted slaves from Virginia who had settled at the opposite end of the state south of Pittsburgh. It is not always easy to identify the individuals, whether enslaved, free Blacks or whites who aided escapees such as Banks.[3]

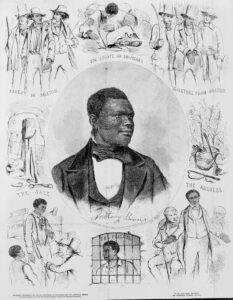

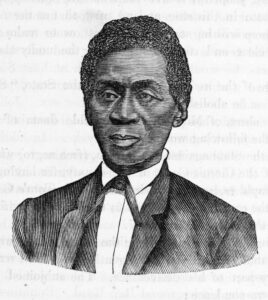

Rev. Samuel Green (NYPL)

If we are unable to identify those in Front Royal who assisted Banks, we get a glimpse into local support in the case of Reverend Samuel Green on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. It was clear to local authorities in 1858 that Green was implicated in escapes from the area. It was rumored he was related to Harriet Tubman and had helped her on her many trips south to bring out the enslaved. He had helped his son, a former slave, get to Canada and had even visited him there. Try as they may, the authorities, as they indelicately observed, could not put the ropes on Green. They knew the route escapees regularly took out of Cambridge, Maryland passed close to Green’s home. Following another group escape, the local police raided the home where they found incriminating evidence including maps, train timetables and a letter from his son in Canada suggesting it was time to send out the next contingent of runaways. None of this was enough evidence to tie Green to the escapes. But during the raid, they found a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin which violated an 1841 state law banning free Blacks from possessing abolitionist literature or information. The state silenced Green by sentencing him to ten years in the state penitentiary.[4]

Support from whites deeply troubled local authorities. F. George Cope, a well-known grocer in Louisville, Kentucky, helped Rachel, a twenty-six-year-old enslaved woman, escape to Canada in November 1856. Cope was in love with Rachel and had plans to join her in Canada, but his love was unrequited. Rachel’s owner sued Cope for the loss of his slave. Although he was never convicted of the crime, the case dragged on for years during which time Cope languished in prison. State penitentiary records, supplemented by fugitive slave advertisements, provide a valuable archive to address the extent of white and Black support for fleeing slaves. [5]

In early 1855, two unnamed whites, one a woman, accompanied Phillip Nettles, supposedly a free Black, onto a ship about to leave Baltimore for Jamaica. The captain hired Nettles as a cook, but it soon became clear that Nettles could not cook. In fact, he was not free but an enslaved man named John Anderson. Rather than drop Anderson off at any of the ports-of-call along the Atlantic coast and face the prospect of being charged with harboring a slave, the captain clapped Anderson in chains and continued to Jamaica. Once the brig dropped anchor in Savanna-la-Mar, boats filled with locals paddled out to the ship, freed Anderson, and took him before a local magistrate who declared him a free man. When asked why he had come to Jamaica, Anderson spoke for many: “I have been kept in bondage and hearing that this was a free country I tried to get here.” We need to take a deeper look at the ways free soil beyond the United States, such as Jamaica and the Bahamas, affected the coastal slave trade along the Atlantic by providing a free space for fugitive slaves. [6]

There is no doubt that the assistance of Blacks and whites played a critical role in the operations of the Underground Railroad in the North. Those who arrived in Pittsburgh before Henry Banks did could rely on African Americans who staffed local hotels to guide them to members of the Philanthropic Society, a Black vigilance committee that is reputed to have never lost a freedom seeker. That may explain why the city became a haven for escaping fugitives. As the impact of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law bore down on African American communities throughout the North, one Pittsburgh editor was surprised to discover how many fugitive slaves were residents of the Black community when scores of them left for Canada in the weeks after President Millard Fillmore signed the law. All along the divide between slavery and freedom, African Americans, as Keith Griffler shows, were “central to the development and operation of the Underground Railroad.” [7]

There is no doubt that the assistance of Blacks and whites played a critical role in the operations of the Underground Railroad in the North.

After their dramatic escape from slavery in Georgia in 1848, William and Ellen Craft were directed to a Black hotelier who sent them to Robert Purvis who, in turn, directed them to a Quaker family on a farm just outside Philadelphia. When in 1827 James Pembroke left slavery in northern Maryland and entered Pennsylvania, William and Phebe Wright, leaders of the Underground Railroad in Adams County, took him in and employed him on their farm. Although the advertisement announcing Pembroke’s escape suspected he could read and write, the newly freed man recalled that the Wrights taught him to read, write, and cipher. After months with the Wrights, Pembroke, now known as J. W. C. Pennington, left for the anonymity and relative safety of New York City, where he became active in the city’s vigilance committee. Years later, Pennington would officiate at the wedding of Frederick Bailey (later Douglass) and Anna Murray after his escape from slavery in Baltimore. From his new home in Rochester, in Churchill’s “free soil region,” Douglass became involved in the effort to protect those who settled in the city and to guide those who chose to move on to Canada. It was a rare event when fugitives were returned from this area.

Stories of the Underground Railroad need to include the activities of those, Black and white, who went south to free slaves. Much of Harriet Tubman’s activities are now well known, but there were others who defied similar odds to bring slaves out. Some paid for it with their lives. Seth Concklin managed to get the family of Peter Still out of Alabama in early 1851. They got as far as Indiana where they were captured. Concklin’s body was found floating in the Ohio River. The escapees were returned. In December 1848, Richard Dillingham was caught transporting slaves out of Nashville, Tennessee. Dillingham died of typhoid in prison. Calvin Fairbank, an Oberlin graduate, served fourteen years of a fifteen year sentence in the Kentucky state penitentiary for aiding an enslaved woman named Tamar to escape from Louisville (for his second spell in Kentucky prison) before he was pardoned in 1864. The operations of the Underground Railroad in southern states were filled with stories of unnamed and almost mythical “white men” and free Blacks who were involved in helping slaves escape. Louis Talbert escaped from northern Kentucky in 1845 and made his way to eastern Indiana where he was aided by Levi Coffin and members of the local Underground Railroad. Talbert would later return multiple times to Kentucky to take out family and friends. This is an area that cries out for further examination. They were just a few of what William Still described as a “long list” of people who “suffered and died in the cause of freedom.” [8]

Finally, we need to come to grips with the many ways that the crisis over fugitive slaves influenced abolitionist views of slavery. Those who ran vigilance committees such as William Still in Philadelphia and Sydney Howard Gay in New York City spent hours interviewing those who made contact with their organizations. These freedom seekers provided invaluable details about the nature of slavery. For many abolitionists it was their initial exposure to first-hand information about the ways of slavery, the sort of information that no book or pamphlet could detail. Those who settled in northern cities and towns came to play pivotal roles in the abolitionist movement. Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Jermain Loguen, Henry Bibb, the Crafts and many more spoke of slavery in ways that had a profound effect on their co-workers in the movement. Consequently, when slave catchers came to Boston in search of the Crafts, the Black community and their white supporters rallied to protect them. Leading that effort was Lewis Hayden who had escaped from Kentucky with his wife aided by Calvin Fairbank. The sight of Anthony Burns being returned to slavery under military escort in 1854 left otherwise conservative supporters of the movement stunned. It was rumored a “large amount of money” had been raised for a rescue. Some proposed the formation of secret societies to prevent such returns to slavery. At a meeting of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, there were calls for abandoning non-violence for more direct action. Some joined the “Anti-Man Hunting League” an organization that planned to kidnap the kidnappers of fugitive slaves. Even Amos Lawrence, a Cotton Whig, was radicalized by events. “We went to bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs,” he wrote, “and waked up stark mad Abolitionists.”[9] We need to understand the ways freedom seekers influenced such radicalization.

Unspooling these stories of fugitive slaves and those who assisted them in both the South and North promises to widen our understanding of the Underground Railroad.

Discussion Questions

- What do the stories of freedom seekers such as Henry Banks or operatives such as Rev. Samuel Green begin to reveal about the nature of the Underground Railroad?

- Why does Blackett claim that studies of the Underground Railroad “need to include the activities of those, Black and white, who went south to free slaves”?

- How might the stories of fugitives and their struggles have influenced the abolitionist movement?

Citations

[1] Stanley Harrold, Border War. Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Robert H. Churchill, The Underground Railroad and the Geography of Violence in Antebellum America, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020). Eric Foner describes the URGG as a puzzle, many of whose parts are missing. See Gateway to Freedom. The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015).

[2] John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). See also essays in Damian Alan Pargas, ed., Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018).

[3] R.J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 308-311.

[4] Blackett, 316-18.

[5] See J. Blaine Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002).

[6] See Jeffrey R. Kerr-Ritchie, Rebellious Passage: The Creole Revolt and America’s Coastal Slave Trade (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019) and Matthew J. Clavin, Aiming for Pensacola. Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015).

[7] Keith P. Griffler, Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004).

[8] William Still, The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872).

[9] Quoted in Blackett, 428.

Author Profile

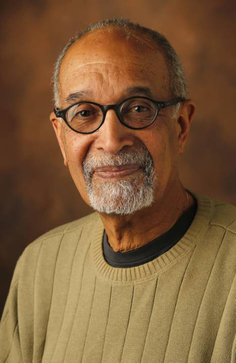

R.J.M. BLACKETT is an emeritus professor of history at Vanderbilt University, where he held the Andrew Jackson Chair. He specializes in United States and Caribbean history, particularly their efforts to end slavery and racial discrimination. Previously, he was the visiting Harmsworth Professor at Oxford University and taught at the University of Pittsburgh, Indiana University, and the University of Houston. He received his bachelor’s degree in International Relations from the University of Keele, England and his master’s degree in American Studies from the University of Manchester, England. He is the author of numerous books including The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (Cambridge, 2018).

R.J.M. BLACKETT is an emeritus professor of history at Vanderbilt University, where he held the Andrew Jackson Chair. He specializes in United States and Caribbean history, particularly their efforts to end slavery and racial discrimination. Previously, he was the visiting Harmsworth Professor at Oxford University and taught at the University of Pittsburgh, Indiana University, and the University of Houston. He received his bachelor’s degree in International Relations from the University of Keele, England and his master’s degree in American Studies from the University of Manchester, England. He is the author of numerous books including The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (Cambridge, 2018).

Additional online resources for RJM Blackett

- INTERVIEW: Black Perspectives with ASALH (2018)

- INTERVIEW: Q&A With History Today (March 2023)

- VIDEO: Making Freedom (C-SPAN, 2016)

- VIDEO: Captive’s Quest (GLI / Yale, 2018)