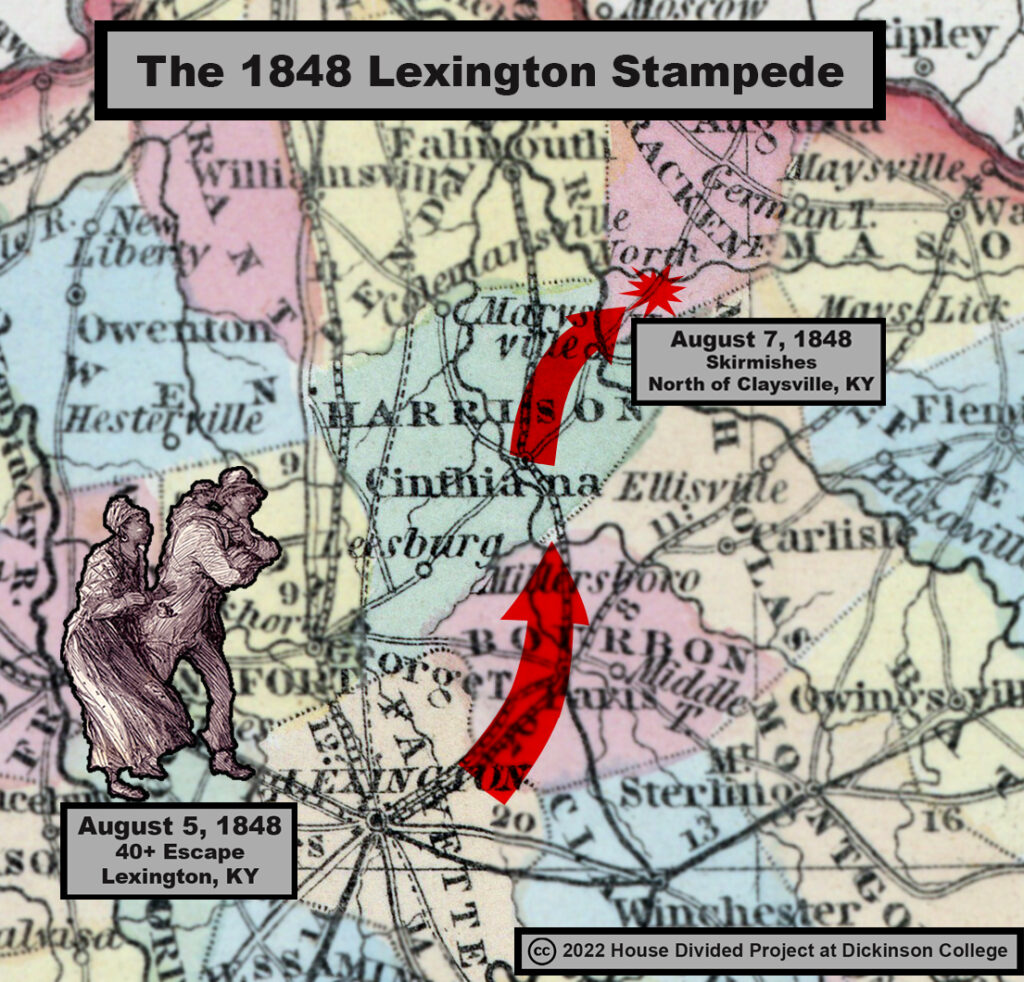

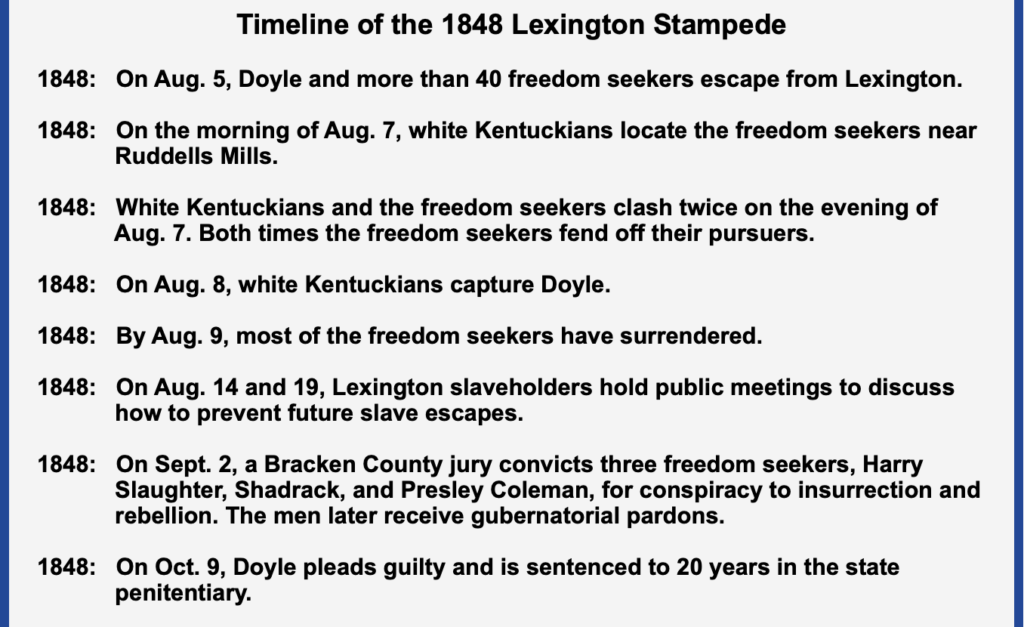

DATELINE: AUGUST 5, 1848, LEXINGTON, KY

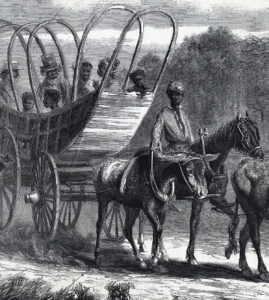

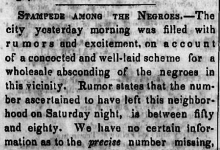

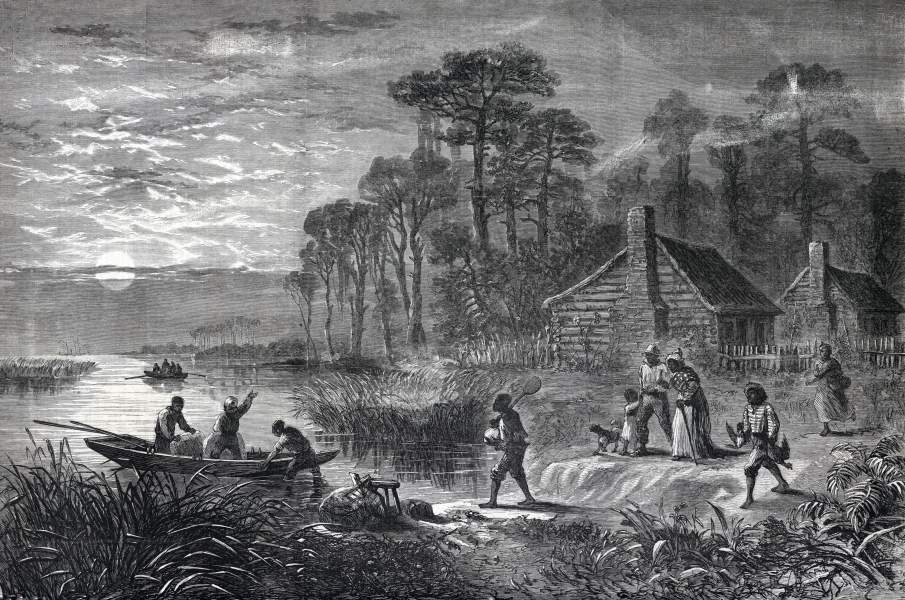

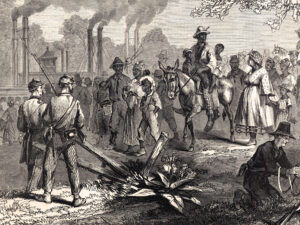

The sound of spirituals and dancing startled the white residents in Lexington, Kentucky from their sleep on Saturday night, August 5, 1848. Enslaved Kentuckians had gathered from miles around to hold another religious meeting just outside town. Annoyed but not alarmed, Lexington slaveholders did their best to ignore the festivities. But this occasion was different. When the services concluded, more than 40 enslaved men “arrayed in warlike manner,” armed themselves with “guns, pistols, knives and other warlike weapons,” and started north from Lexington along the Russell Cave Road. An Irish immigrant and professed ally of the freedom seekers, Edward J. “Patrick” Doyle, led the group towards the Ohio River. Newspapers in Kentucky and across the nation quickly labeled the mass escape attempt a “slave stampede.” [1] Perhaps more than any other single episode, the Lexington stampede helped define the powerful new “slave stampede” metaphor as an escape involving large numbers of heavily armed freedom seekers––what many pro- and antislavery readers alike understood as a form of mobile insurrection.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

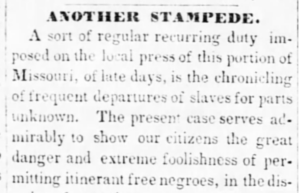

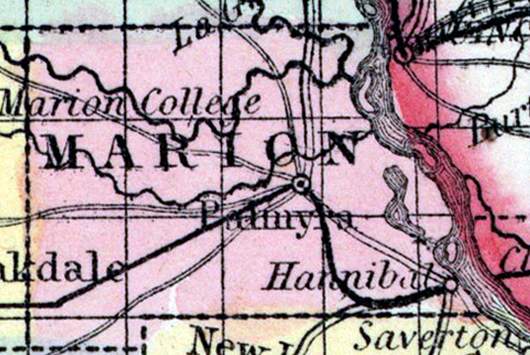

In August 1848, the “slave stampede” metaphor was barely a year old. Editors for the Lexington Atlas thought the term well-suited to describe the mass escape from their community and ran the headline “Stampede Among the Negroes” on Tuesday, August 8. Other papers in Kentucky and across the nation followed suit. Over 40 articles nationwide referred to the escape as a “stampede,” with some newspapers styling it the “great slave stampede” or “the giant stampede of negroes from the interior of Kentucky.” [2]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Edward J. “Patrick” Doyle had a checkered past by the time he suddenly appeared in Lexington, Kentucky during the summer of 1848. An Irish immigrant in his early 20s, Doyle had been expelled for bad behavior from the St. Rose Priory in Springfield, Kentucky, and again from the St. Thomas Seminary in Bardstown. Doyle then vocally renounced his Catholicism, claimed that vengeful Catholics had tried to murder him, and secured admission to Centre College in Danville, Kentucky by assuring school officials that he was a sincere Protestant convert. Academics were the least of Doyle’s troubles, however. Doyle’s criminal record was extensive. Authorities in Louisville had arrested him for trying to sell free Black Ohioans into slavery. Only weeks before Doyle arrived in Lexington in 1848, officials in Frankfort had jailed him on theft charges. Historian James Prichard has concluded that at his core, Doyle was an opportunist “willing to play both sides of any controversy if it lined his pockets.” [3]

But none of that was known to enslaved people near Lexington, Kentucky who saw Doyle as a potential liberator. Soon after Doyle arrived in Lexington, he began approaching enslaved residents and offering to guide them to freedom––for a fee. “A man named Doyle came to me and told me that he would pilot me across the Ohio river for $100,” recalled Harry Slaughter, then 32-years-old and enslaved near Lexington. Slaughter had extra motivation. The rest of his family and his girlfriend were free, and Slaughter “wanted to marry my sweetheart as a free man and not as a slave.” [4]

An enslaved man named Washington later testified that Doyle approached him four weeks before the escape. At first, Doyle simply “asked me to show him the way to the neighbouring house.” But soon after the pair set off, Doyle “asked me to show him a secret place as he had some communications to make.” As Washington led Doyle to a nearby sink hole where they could hold a private conversation, Doyle “locked his arm in mine & said he was just from Canada where he wished me to go and held out many fair promises to tempt me.” Doyle assured Washington that “the land was just as good, that I would be free & could get any office I wished and be as much respected as my master was here.” [5]

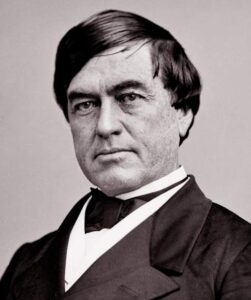

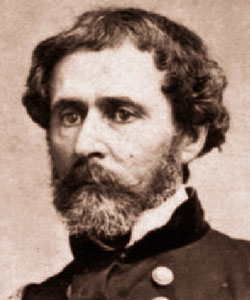

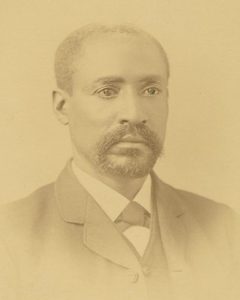

Kentucky slaveholder and antislavery politician Cassius M. Clay (Library of Congress)

Doyle and enslaved Kentuckians managed to assemble a large group of freedom seekers to make a dash for the Ohio River. The enslaved came from the households of some of Lexington’s most prominent residents, including Jack, an enslaved man who escaped from prominent Kentucky politician and gradual emancipation advocate Cassius M. Clay. Reports placed the total number of freedom seekers anywhere from 40 to 80. For its part, the Lexington Atlas calculated that 66 freedom seekers had escaped. Harry Slaughter remembered that the group consisted of “Doyle and forty-five of us negroes.” What is clear is that the escape was carefully planned down to the pretext and the day of the week. Leaders of the escape correctly assumed that assembling for a religious meeting would allay any suspicions local whites might have about such a large gathering of enslaved people, and also that by leaving on a Saturday night their absence would go mostly unnoticed by slaveholders until Monday. [6]

Doyle intended the mass escape to look like a military movement. On Sunday, Doyle produced a “saddle ba[g] full of pistols… & distributed them to the boys,” telling the freedom seekers “they would need them to kill the wolves… in Canada & on the road.” According to multiple freedom seekers, Doyle also “endeavor[ed] to make them march in… military order.” “We all marched in ranks,” a freedom seeker named Edmond later testified. “Those with pistols were in front & the rear & those with knives in the middle.” Doyle “galloped up & down from one end to the other & forbid our talking,” reported Washington. Doyle also threatened to kill any freedom seekers who contemplated leaving the stampede and returning home. “Doyle said he would blow the first one down who deserted,” recalled Edmond. [7]

Traveling all night Saturday, hiding during the daylight hours, and traveling again all night Sunday, the freedom seekers covered 25 miles from Lexington to Ruddells Mills undetected. The runaways fed themselves on ears of corn gathered along the way. But on Monday morning, August 7, local residents caught wind of the mass escape quietly passing through their neighborhood. Two young boys spotted the freedom seekers concealed in the woods near Ruddells Mill and rushed to notify local authorities. Around the same time, two freedom seekers (who were not identified by name) enslaved by Lexington lawyers T. Scott and B. Gratz strayed from the group in search of food and walked right into slaveholders in nearby Claysville. The two captives eventually admitted that there were “between 40 and 70 negroes… in the neighborhood, concealed in the woods,” which was “the first intimation the people of Harrison [county] had of the stampede.” To make matters worse for the freedom seekers, large crowds had already assembled at local polling places for that day’s gubernatorial election. Voters quickly mobilized in pursuit of the runaways. [8]

The freedom seekers and a slave-catching posse clashed twice on Monday evening, August 7, and both times the freedom seekers beat back their would-be captors and wounded pursuers. The first fight began around 7 pm, when Claysville physician Dr. B.F. Barkley and his posse of 10 men overtook the freedom seekers who were “encamped and fortified” northeast of Claysville on the Germantown road. Heavily armed and outnumbering their pursuers, the freedom seekers opened fire and forced Barkley’s ten men to retreat. One shot struck Harrison County resident and Mexican War veteran Charles H. Fowler in the left kidney, badly wounding him. [9]

As the fighting intensified, Doyle appeared to get cold feet. The stampede’s self-anointed leader mounted his horse and seemed intent on fleeing. Multiple enslaved witnesses saw Harry Slaughter grab the bridle and pull Doyle off the horse, shouting that Doyle “should not leave them after he had got them in he must say.” Doyle then tried to shoot his horse, but Slaughter intervened, protesting that the animal “had done no harm.” [10]

Minutes later, 10 more Harrison County residents arrived and Barkley made a second attempt to subdue the freedom seekers. Once again, the freedom seekers repulsed the assault and wounded yet another pursuer, peppering Joseph Duncan’s hat with bullet holes and then shooting his horse out from under him, “throwing him in the midst of the negroes.” Duncan used his revolver at close range and “succeeded in fighting his way through them,” though not before a freedom seeker knocked out a tooth. Still outnumbered, Duncan and the rest of Barkley’s posse retreated for a second time. “They [the freedom seekers] appear determined to fight for every inch of ground,” concluded the pursuers, “and are commanded by a white man or more.” Pursuers reported that Doyle “encouraged the blacks to rally and fire, at all times, when our boys would come on them.” [11]

But the freedom seekers had lost the advantage of secrecy, and soon would lose their advantage in numbers too. As reports of the stampede and fighting spread, Kentucky militia general Lucius Desha mobilized several hundred men from Harrison and Bracken counties to surround the freedom seekers and block their path to the Ohio River. Meanwhile, Cynthiana residents informed Lexington slaveholders by express dispatch that “your negroes are supposed to be surrounded” near the Harrison-Bracken county line and requested that the city send a “fresh set of men immediately, say 50 or 100, well armed.” To make the point abundantly clear, Cynthiana residents added tersely: “Send all you can and speedily, or all will be lost…. Come if you want any of your negroes. We have not time to say more.” Within hours of the dispatch reaching Lexington, authorities called a public meeting and quickly raised “fifty or sixty armed men.” [12]

Meanwhile, the stampede had lost its momentum and its leader. Harry Slaughter had prevented Doyle from abandoning the freedom seekers during the first skirmish, but Doyle apparently slipped away unnoticed during the second fight. In his absence, the military-like discipline Doyle had enforced unraveled. As pursuers closed in, “the men scattered in all directions,” remembered Slaughter. According to Washington, “all wished then to return home.” Demoralized and leaderless, “we became scattered some going ahead & others squatting around in the bushes,” Washington later testified. “I was completely lost & saw the boys were no more untill we were caught. I gave myself up & was exhausted from hunger & fatigue.” [13]

Harry Slaughter and Shadrack were among those who pressed on. The pair stuck together and “determined to get to the Ohio river, if possible.” The two men crossed into Bracken County and were approaching the Licking River near Milford when pursuers overtook them. “We plunged in and swam and waded across,” but a posse of a dozen men quickly surrounded them, subduing Shadrack while Slaughter continued to resist. “I cried out in a loud voice: ‘I will not be taken! The man that kills me is my friend! I had rather die here and now than go back to slavery!'” Slaughter had thrown away his bowie knife “for fear that I might kill one of them,” but proudly remembered that “I fought them for five minutes with my fist” before finally surrendering. In addition to Slaughter and Shadrack, vigilant whites had captured nine to 10 freedom seekers by Tuesday night, and around 40 by Wednesday evening (20 confined in the Claysville jail, and another 19 in Brooksville). [14]

The most anticipated capture came on Tuesday, when a scouting party apprehended Doyle about eight miles north of Claysville along Drift Run. The captors “were with great difficulty restrained from hanging the prisoner on the spot,” but General Desha intervened and had Doyle brought before local authorities in Claysville and then moved to the county jail in Cynthiana. There, a crowd of “several hundred” threatened to storm the jail, chanting “Kill him! Shoot him!! Burn him!!” Fearing that angry residents might make good on their threats, Dr. Barkley returned that night and quietly transferred Doyle from Cynthiana to the Lexington jail. [15]

AFTERMATH

To slaveholders, the mass escape had looked alarmingly like a mobile insurrection. Decades later, freedom seeker Harry Slaughter would insist the stampede was not an insurrection, although he acknowledged the freedom seekers’ intention to defend themselves with force if necessary. “The movement was afterwards referred to as an ‘insurrection,’ but it was misnamed,” Slaughter explained. “We did not intend to fight unless attempts were made to capture us, but we pledged ourselves that if we were overtaken by white men and they made an effort to capture us we would fight as long as possible.” [16]

To slaveholders, the mass escape had looked alarmingly like a mobile insurrection. Decades later, freedom seeker Harry Slaughter would insist the stampede was not an insurrection, although he acknowledged the freedom seekers’ intention to defend themselves with force if necessary. “The movement was afterwards referred to as an ‘insurrection,’ but it was misnamed,” Slaughter explained. “We did not intend to fight unless attempts were made to capture us, but we pledged ourselves that if we were overtaken by white men and they made an effort to capture us we would fight as long as possible.” [16]

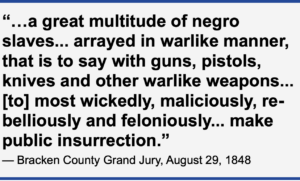

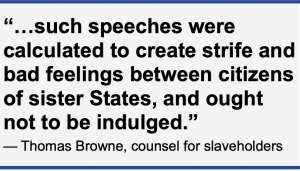

Slaughter’s distinction between defensive and offensive violence did not resonate with white Kentuckians. The criminal charges eventually brought against Doyle and Slaughter accused them of leading “a great multitude of negro slaves… arrayed in warlike manner, that is to say with guns, pistols, knives and other warlike weapons… [to] most wickedly, maliciously, rebelliously and feloniously… make public insurrection.” [17] When several of the enslaved participants went on trial, Judge Walker Reid’s instructions to the jury focused almost exclusively on which enslaved people fought in the two skirmishes, the part of the stampede which most closely resembled a slave rebellion. “All who were in company armed and ready to aid, at the time they fired upon their owners and other white men, who attempted to take them up, are guilty,” Reid opined. [18] In fact, the most enduring impact of the escape may well have been to help define the new “slave stampede” metaphor as a form of mobile insurrection.

During the ensuing trial, enslaved participants downplayed the stampede’s revolutionary edge, insisting that they just wanted to escape peacefully but were deceived by Doyle into waging violent resistance. “I had no intention to incite an insurrection [and] did not wish to harm a living soul,” the enslaved Washington maintained under cross-examination. “I wished to leave peaceably did not wish nor expect a fight.” Washington insisted he “was only allured by the insidious promises and advantages held out in the prospective by the white man.” Another freedom seeker, Edmond, made a similar statement under cross examination. “I wished to escape as easially [sic] as possible and did not wish to fight nor did I intend to do so.” Washington and Edmond may well have been sincere in their statements, but they also may have sought to play into white Southerners’ assumptions that large escapes and revolutionary resistance required white leadership. Indeed, the trial records also contain hints that at least some of the enslaved freedom seekers may not have been as reluctant to fight for their freedom as they later played it off. For instance, one white witness overheard Presley Coleman tell “the others to recollect the watchword was ‘Victory or Death.'” [19]

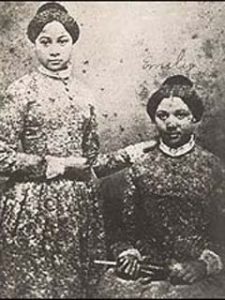

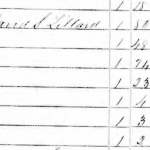

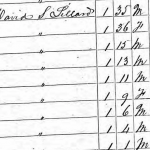

Rather than prosecute all the freedom seekers, Bracken County authorities singled out seven alleged ringleaders they believed had helped Doyle orchestrate the stampede: Harry Slaughter (held by Richard Pindell), Shadrack (held by Thomas Christian), Jack (held by politician Cassius M. Clay), Bill Griffin (held by John Chism), Presley Coleman (held by John Wardlow), Anderson (held by Alexander Prewett), and Jasper (held by Samuel R. Bullock). A grand jury indicted the seven men for assault with intent to kill Charles Fowler (the badly wounded posse member) and on insurrection and rebellion charges. Following a three-day trial that spanned from August 30 to September 1, jurors acquitted Jack, Bill Griffin, Anderson, and Jasper on both counts, but convicted Slaughter, Shadrack, and Presley Coleman for conspiracy to insurrection and rebellion. The court sentenced the three enslaved men to hang. [20]

Slaveholders orchestrated a petition campaign to secure gubernatorial pardons for all three condemned men, repeating the logic that the enslaved participants had been hoodwinked by Doyle. H.C. Pindell, the brother of Harry Slaughter’s enslaver, voiced his belief that Slaughter “was led off by the persuasions of Doyle perhaps by such overwrought pictures of the blessing son liberty as few men in bondage could resist. It would seem hard therefore to have him hung,” Pindell argued, “while Doyle escapes with a short confinement in the penitentiary.” Slaughter’s former enslaver also petitioned for his pardon, similarly reasoning that “this misstep of his should be wholy [sic] attributed to the wily persuasions of Doyle.” [21]

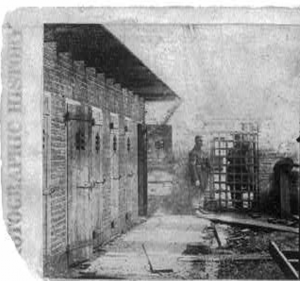

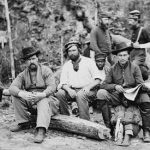

Slave sale at the Cheapside auction block in the public square at Lexington, Kentucky (Explore KY History)

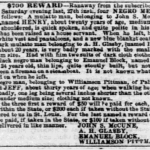

Slaveholders secured gubernatorial pardons for all three condemned men, though the assumption was that the rebellious men who had escaped the gallows would be sold to the Deep South as a warning to other enslaved people. That was the fate that seemed to be in store for Harry Slaughter. After Slaughter received his pardon, his slaveholder Sidney Edmiston moved him from the Bracken County prison to Pullum’s slave pen in Lexington, where he remained for “a month or more.” But Slaughter eventually persuaded Edmiston to allow him to purchase his freedom. “I immediately borrowed the money and married my sweetheart,” Slaughter recalled. The fate of Shadrack, Presley Coleman, and the countless other freedom seekers never charged with crimes but returned directly to their slaveholders remains unclear, though few were likely as fortunate as Slaughter. In December, a Memphis, Tennessee newspaper hinted that most of the recaptured freedom seekers had been sold south as punishment for their participation in the stampede. [22]

White Kentuckians hoped to set an example with Doyle. A Maysville, Kentucky journalist thought that the “fate of Doyle may teach others… that Kentucky is a dangerous soil for Abolitionist[s] to tread upon.” Following a preliminary hearing on August 17, a grand jury in Fayette County indicted Doyle for enticing slaves and inciting insurrection. Lexington politician, future U.S. vice president, and future Confederate John C. Breckenridge served as Doyle’s defense counsel. To be sure, Breckenridge remained firmly proslavery. Doyle’s conviction was certain, and Breckenridge’s presence as Doyle’s attorney merely reflected Lexington elites’ desire to demonstrate respect for law and order over vigilante violence. Doyle plead guilty on October 9 and Judge Walker Reid sentenced him to 20 years in the state penitentiary, where he died in 1863. [23]

Few abolitionists mourned Doyle’s fate. Just several years earlier, antislavery activists had rallied behind Calvin Fairbanks and Delia Webster, abolitionists who had also been convicted in Kentucky (not for inciting insurrection but rather for helping freedom seekers escape in violation of the state’s slave stealing statutes). But most antislavery newspapers viewed Doyle as an opportunist rather than a committed antislavery activist. An antislavery paper in Ohio sniped that Doyle had been “caught in his own trap” and suspected that if Doyle had succeeded, “his design was to betray them [the freedom seekers] to the kidnappers and secure the reward for their recapture.” In the words of one antislavery editor, “we feel much less pity for him than for the innocent men who trusted him as their friend.” [24]

As the trials unfolded, Lexington slaveholders gathered to debate what had gone wrong. Two public meetings held at the Court House on Monday, August 14 and Saturday, August 19 debated and recommended multiple proposals to city, county, and state authorities. Lexington slaveholders asked city officials to “organize a force that will suppress the flocking of slaves to the City without such written permissions form their owners,” and outlined a county-sponsored slave patrol to prevent “nocturnal gatherings” such as the one that had precipitated the stampede. Meanwhile, slaveholders suggested that the state legislature both enact new restrictions on free African Americans residing in the state and a new state tax to deter “peddlers and itinerant vendors” from traveling the countryside and having contact with enslaved people. In September, the Fayette County Court acted upon the committee’s recommendation and took steps to create a new patrol by dividing the county into “suitable districts.” [25]

The Lexington stampede also figured in arguments both for and against gradual emancipation during Kentucky’s 1849-1850 constitutional convention. A Tennessee editor noted with concern that many Kentucky slaveholders already were selling enslaved people farther south, including “when a stampede of 70 or 80 negroes takes place in Kentucky, and are recovered, they are at once handcuffed and sent South.” Later in July 1849, a supporter of gradual emancipation cited the ”slave stampede in Fayette last year” to insist the non-slaveholding whites had a right to weigh in on the future of slavery in the state. “Some 70 or more negroes ran away and passed through portions of three or four large slaveholding counties, and could not be arrested until they got among the non-slaveholders of Bracken county,” he reminded readers. [26]

FURTHER READING

The Lexington Atlas provided the most detailed contemporary reports about the escape and pursuit. [27] Harry Slaughter’s 1897 interview with the New York Sun, which billed him as the “last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection,'” remains the only extant account from a freedom seeker’s perspective. [28]

Scholars have discussed the mass escape attempt, but not in connection with the “stampede” metaphor. Historian J. Winston Coleman used court records to reconstruct the details of the escape in his study, Slavery Times in Kentucky (1940). Herbert Aptheker drew on Coleman’s research and situated the escape as an insurrection in his landmark study, American Negro Slave Revolts (1943). In a pair of articles (1998 and 2000), historian John Leming, jr. concluded that the Lexington episode was the “largest single slave uprising in Kentucky history.” In a 2023 essay entitled “‘This Priceless Jewell––Liberty’: The Doyle Conspiracy of 1848,” historian James Prichard emphasizes Doyle’s dubious past while also expertly documenting the legal fallout from the escape for Doyle and the captured freedom seekers. [29]

[1] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 8, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “For the Lexington Atlas,” August 10, 1848; Maysville (KY) Campaign Flag, “The runaway slaves again,” August 18, 1848; Omaha (NE) World-Herald, “Free Negro For 46 Years: Last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection’ Tells of Attempt to Escape,” August 16, 1897; Indictments, Bracken County (KY) Circuit Court, August 29, 1848, typescript copies in box 1, folder 8, J. Winston Coleman papers, University of Kentucky. The Slave Stampedes on the Southern Borderlands project would like to thank James Prichard of Lexington, Kentucky for sharing information from his extensive files and his forthcoming essay on the escape, which will be published in the edited volume Slavery and Freedom in the Bluegrass State (University of Kentucky Press, 2023).

[2] Articles that reference the escape as a stampede include: Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 8, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 9, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Abolition–Runaways–Public Meeting–Great Excitement–Threats of Vengeance,” August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 11, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, “Abolition – Runaways – Public Meeting,” August 11, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, August 12, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 12, 1848; Buffalo (NY) Commercial, “The Kentucky Runaways,” August 14, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, “Doyle – The Negro Abductor,” August 14, 1848; New York (NY) Evening Post, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 15, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Public Meeting,” August 15, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, August 16, 1848; New York (NY) Daily Herald, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 16, 1848; Buffalo (NY) Commercial, “The Runaway Slaves,” August 16, 1848; New York (NY) Evening Post, “The Runaway Slaves,” August 18, 1848; Cleveland (OH) Herald, “The Absconding Slaves,” August 19, 1848; Baltimore (MD) Sun, “The Kentucky Slave Stampede,” August 19, 1848; Buffalo (NY) Daily Republic, “Kentucky Run-Away Slaves,” August 19, 1848; Fayette (MO) Boon’s Lick Times, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 19, 1848; Pittsburgh (PA) Daily Morning Post,”Doyle, The Negro Abductor,” August 21, 1848; Middlebury (VT) Galaxy, “Slave Stampede in Kentucky,” August 22, 1848; Boston (MA) Weekly Messenger, “The Runaway Slaves,” August 23, 1848; Baltimore (MD) Sun, “Kentucky Slave Stampede,” August 23, 1848; Vidalia (LA) Concordia Intelligencer, “Negro Stampede in Kentucky,” August 26, 1848; New Orleans (LA) Crescent, August 28, 1848; Brooklyn (NY) Evening Star, “The Kentucky Slave Stampede,” September 12, 1848; Boston (MA) Liberator, “The Kentucky Slave Stampede,” September 22, 1848; Hallowell (ME) Maine Cultivator and Hallowell Gazette, “The Kentucky Slave Stampede,” October 14, 1848; Baltimore (MD) Sun, “Conviction of Doyle in Kentucky,” October 17, 1848; Alexandria (VA) Gazette, “Doyle Sentenced in Kentucky,” October 18, 1848; Windsor (VT) Journal, October 20, 1848; Sunbury (PA) American, October 21, 1848; Buffalo (NY) Courier, October 21, 1848; Camden (SC) Weekly Journal, October 25, 1848; New Orleans (LA) Crescent, October 27, 1848; Mobile (AL) Alabama Planter, “Conviction of Doyle in Kentucky,” October 30, 1848; Dubuque (IA) Weekly Miners Express, November 14, 1848; New Lisbon (OH) Anti-Slavery Bugle, “Caught in His Own Trap,” November 17, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Democrat, “Slavery Emancipation in Kentucky,” December 7, 1848; Louisville (KY) Examiner, “To the Citizens of Jefferson County,” July 28, 1849.

[3] Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, “Doyle – The Negro Abductor,” August 14, 1848; Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, August 16, 1848; James Prichard, “‘This Priceless Jewell–Liberty!:’ The Doyle Conspiracy of 1848,” lecture at Filson Historical Society, Lexington, KY, recorded July 30, 2021.

[5] Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848.

[6] Indictments, Bracken County (KY) Circuit Court, August 29, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 8, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “For the Lexington Atlas,” August 10, 1848.

[7] Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848; H.C. Pindell to Gov. William Owsley, August 25, 1848.

[8] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848; Omaha (NE) World-Herald, “Free Negro For 46 Years: Last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection’ Tells of Attempt to Escape,” August 16, 1897.

[9] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848

[10] Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848.

[11] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Abolition–Runaways–Public Meeting–Great Excitement–Threats of Vengeance,” August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 12, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 15, 1848; Maysville (KY) Campaign Flag, “The runaway slaves again,” August 18, 1848; Omaha (NE) World-Herald, “Free Negro For 46 Years: Last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection’ Tells of Attempt to Escape,” August 16, 1897.

[12] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Abolition–Runaways–Public Meeting–Great Excitement–Threats of Vengeance,” August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848; Maysville (KY) Campaign Flag, “The runaway slaves again,” August 18, 1848.

[13] Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848; Omaha (NE) World-Herald, “Free Negro For 46 Years: Last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection’ Tells of Attempt to Escape,” August 16, 1897;

[14] Omaha (NE) World-Herald, “Free Negro For 46 Years: Last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection’ Tells of Attempt to Escape,” August 16, 1897; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Abolition–Runaways–Public Meeting–Great Excitement–Threats of Vengeance,” August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848; Lewis Collins, History of Kentucky (Covington, KY: Collins, 1874), 2:57.

[15] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848; Maysville (KY) Campaign Flag, “The runaway slaves again,” August 18, 1848.

[17] Indictments, Bracken County (KY) Circuit Court, August 29, 1848.

[18] Judge Walker Reid to Gov. William Owsley, September 2, 1848.

[19] Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848.

[20] Indictments, Bracken County (KY) Circuit Court, August 29, 1848; Prichard, “‘This Priceless Jewell–Liberty!:’ The Doyle Conspiracy of 1848,” lecture at Filson Historical Society, Lexington, KY, recorded July 30, 2021.

[21] H.C. Pindell to Gov. William Owsley, August 25, 1848; Petition of Benjamin F. Graves, et. al., August 26, 1848.

[22] Omaha (NE) World-Herald, “Free Negro For 46 Years: Last survivor of the 1848 ‘Insurrection’ Tells of Attempt to Escape,” August 16, 1897. On the pardons, see Prichard, “‘This Priceless Jewell–Liberty!:’ The Doyle Conspiracy of 1848,” lecture at Filson Historical Society, Lexington, KY, recorded July 30, 2021. In the context of debates about gradual emancipation and the future of slavery in Kentucky, the Louisville Democrat commented: “Already, when a stampede of 70 or 80 negroes takes place in Kentucky, and are recovered, they are at once handcuffed and sent South.” See Memphis (TN) Herald, quoted in Louisville (KY) Daily Democrat, “Slavery Emancipation in Kentucky,” December 7, 1848.

[23] Maysville (KY) Campaign Flag, “The runaway slaves again,” August 18, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 18, 1848; Indictments, Bracken County (KY) Circuit Court, August 29, 1848. For more on Doyle’s trial, see Prichard, “‘This Priceless Jewell–Liberty!:’ The Doyle Conspiracy of 1848,” lecture at Filson Historical Society, Lexington, KY, recorded July 30, 2021.

[24] New Lisbon (OH) Anti-Slavery Bugle, “Caught in His Own Trap,” November 17, 1848; Philadelphia (PA) Freeman, “A Martyr, Or A Judas?,” December 21, 1848.

[25] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “For the Lexington Atlas,” August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “For the Lexington Atlas,” August 11, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Public Meeting,” August 15, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Meeting in Fayette,” August 21, 1848; J. Winston Coleman, Slavery Times in Kentucky (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 95-96. Lexington slaveholders even suggested that county courts be allowed to offer rewards for detecting white Underground Railroad agents.

[26] Memphis (TN) Herald, quoted in Louisville (KY) Daily Democrat, “Slavery Emancipation in Kentucky,” December 7, 1848; Louisville (KY) Examiner, “To the Citizens of Jefferson County,” July 28, 1849.

[27] Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Stampede Among the Negroes,” August 8, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “Abolition–Runaways–Public Meeting–Great Excitement–Threats of Vengeance,” August 10, 1848; Lexington (KY) Atlas, “The Runaway Negroes,” August 11, 1848.

[29] Coleman, Slavery Times in Kentucky, 88-92; Herbert Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943), 338;John Leming, jr., “Bracken County and The Great Slave Escape of 1848,” Northern Kentucky Heritage 5, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 1998): 32-38; Leming, “The Great Slave Escape of 1848 Ended in Bracken County,” The Kentucky Explorer (June 2000): 25-29; James M. Prichard, “‘This Priceless Jewell––Liberty’: The Doyle Conspiracy of 1848,” in Gerald Smith (ed.), Slavery and Freedom in the Bluegrass State: (Re)-visiting My Old Kentucky Home (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2023), 79-109.

at, ridiculed and insulted, for making legal and constitutional efforts to capture the flying refugees”–apparently referring to the Chicago

at, ridiculed and insulted, for making legal and constitutional efforts to capture the flying refugees”–apparently referring to the Chicago

drolly commented that “the Sheriff was at least four days behind time.” In nearby Hunstville, Missouri, the editor of the Randolph Citizen expressed what was fast becoming the general consensus: “There seems to be a poor chance for their recovery.”

drolly commented that “the Sheriff was at least four days behind time.” In nearby Hunstville, Missouri, the editor of the Randolph Citizen expressed what was fast becoming the general consensus: “There seems to be a poor chance for their recovery.”

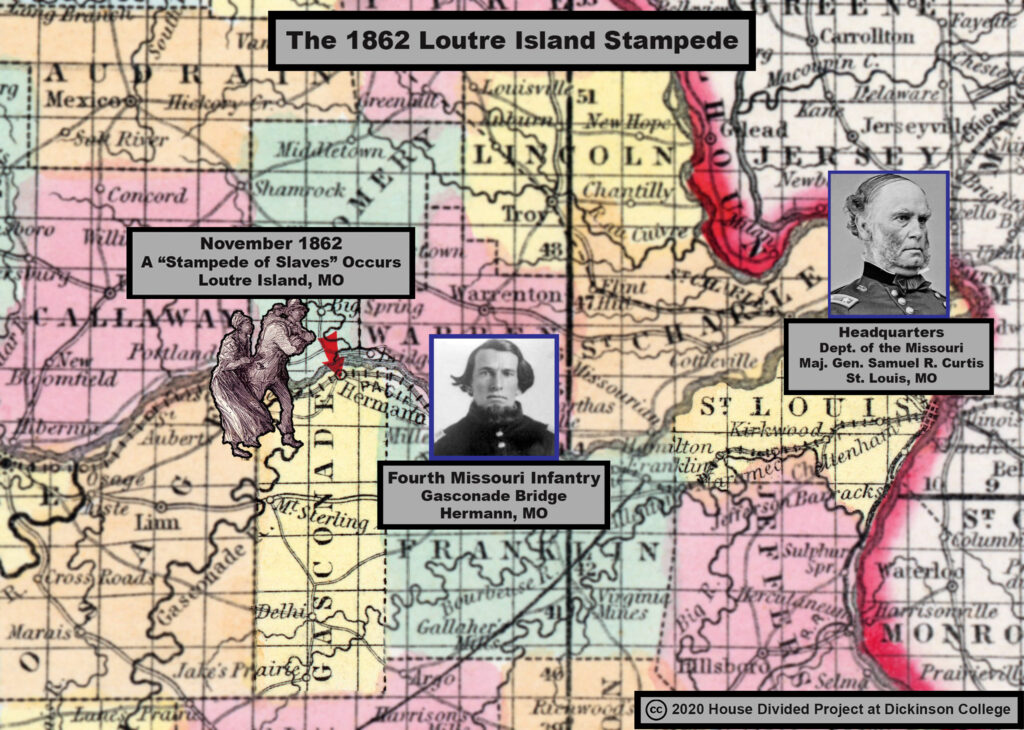

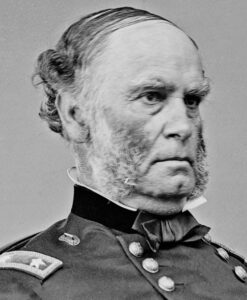

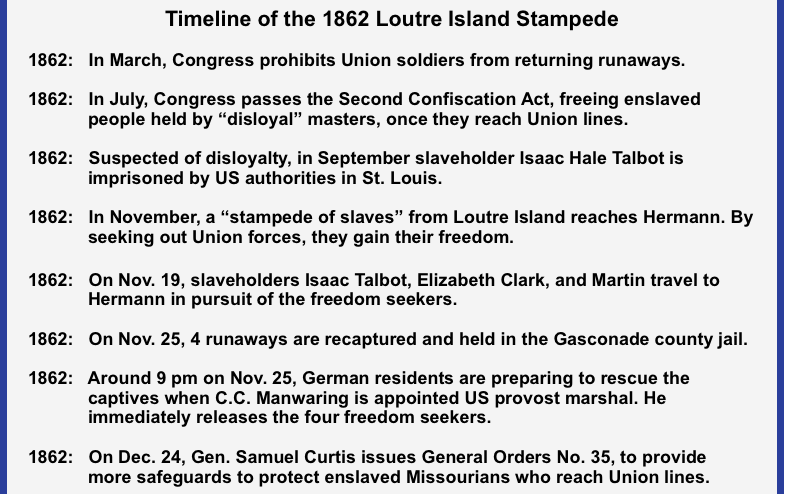

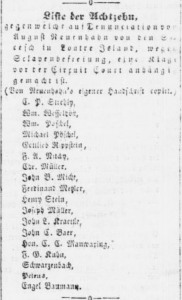

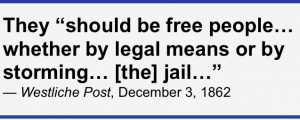

On November 19, not long after Captain Mundwiller permitted the freedom seekers to pass through his lines and ordered them to find work, slaveholders Isaac Talbot, Elizabeth Clark, and Martin travelled to Hermann and sought out the town’s justice of the peace, a Dutch immigrant named John B. Miché. He refused to arrest the freedom seekers under state laws, as the slaveholders insisted he do. Backed by several of the town’s prominent German residents, Miché reasoned that because the state had been under martial law since August 1861, “the matter belonged before the Federal authorities.” Back in St. Louis, the German Westliche Post thundered its approval of Miché’s actions, praising his adherence “to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican.” Undeterred, around a week later the slaveholders cajoled another justice of the peace, a German-born man named Karl Sandberger, to issue the warrants and arrest four freedom seekers, who on Tuesday, November 25 found themselves behind bars at the Gasconade county jail. The news “passed through town and surroundings like wildfire,” wrote one observer, and Hermann’s German population quickly mobilized in protest. By that afternoon, a large crowd had congregated outside the jail, uttering “threats and curses” at the slaveholders and vowing that the captives “should be freepeople” in the morning, “whether by legal means or by storming… [the] jail.”

On November 19, not long after Captain Mundwiller permitted the freedom seekers to pass through his lines and ordered them to find work, slaveholders Isaac Talbot, Elizabeth Clark, and Martin travelled to Hermann and sought out the town’s justice of the peace, a Dutch immigrant named John B. Miché. He refused to arrest the freedom seekers under state laws, as the slaveholders insisted he do. Backed by several of the town’s prominent German residents, Miché reasoned that because the state had been under martial law since August 1861, “the matter belonged before the Federal authorities.” Back in St. Louis, the German Westliche Post thundered its approval of Miché’s actions, praising his adherence “to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican.” Undeterred, around a week later the slaveholders cajoled another justice of the peace, a German-born man named Karl Sandberger, to issue the warrants and arrest four freedom seekers, who on Tuesday, November 25 found themselves behind bars at the Gasconade county jail. The news “passed through town and surroundings like wildfire,” wrote one observer, and Hermann’s German population quickly mobilized in protest. By that afternoon, a large crowd had congregated outside the jail, uttering “threats and curses” at the slaveholders and vowing that the captives “should be freepeople” in the morning, “whether by legal means or by storming… [the] jail.”