This post is the second of three posts on the Camp Nelson Stampede: see also Initial Stampede (Part 1) and Freedom and Community (Part 3)

DATELINE: FALL 1864, WOODFORD COUNTY, KY

For Patsey Leach, an enslaved woman in Woodford County, Kentucky, the worst began after her husband Julius went to Camp Nelson to enlist. “From that time,” Leach testified, slaveholder Warren Wiley “treated me more cruelly than ever whipping me frequently… saying my husband had gone into the army to fight against white folks and he my master would let me know that I was foolish to let my husband go.” Wiley vowed to “’take it out of my back,’ he would “Kill me by picemeal’ [sic].” [1]

By June 1864, the initial stampede to Camp Nelson had forced federal officials to open the ranks to all enslaved men in Kentucky, regardless of their slaveholders’ approval. However, the reworked federal policy still did not clarify the status of enslaved women like Patsey Leach. Undeterred, Leach and countless other enslaved women continued to head to Camp Nelson, where they sought refuge and an opportunity to reunite their families. Braving threats of violence from their slaveholders and all manner of dissuasion from US military officials, enslaved women pressured the US military and lawmakers back in Washington to expand federal policy to provide for the families of Black recruits. Enslaved women’s persistent efforts to reunite their families at Camp Nelson directly inspired a new federal law adopted in March 1865, which explicitly freed the wives and children of Black US soldiers.

MAIN NARRATIVE

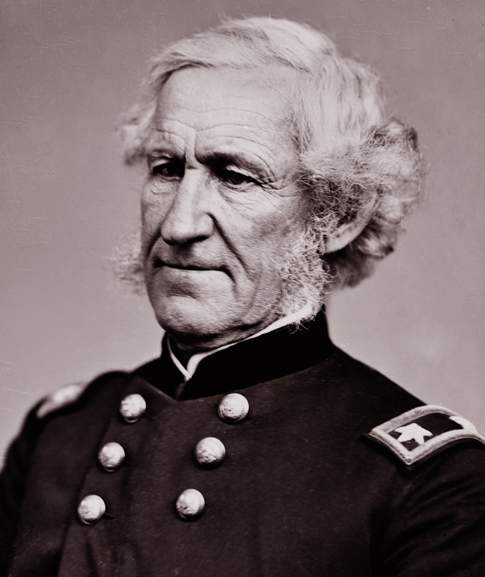

On June 20, 1864, US general Stephen Burbridge confessed that he was not sure about the status of enslaved women and children who were crowding into Camp Nelson alongside their husbands and fathers. Burbridge decided to wait until Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, the army’s top recruiter of African American troops, arrived. In the meantime, Burbridge made clear that “women and children cannot be left to starve” and instructed his subordinates to “establish a contraband camp at Camp Nelson.” [2]

US army adjutant general Lorenzo Thomas (House Divided Project)

When Thomas arrived at Camp Nelson in July 1864, he decided to backtrack. Thomas based his decision on Kentucky’s status as a loyal slave state, as well as his own assumptions that enslaved women and children would be nothing but a drain on army resources. Matters would be different, Thomas explained, in Confederate states where the Emancipation Proclamation applied and all enslaved people, male and female, were free upon reaching US lines. But in a loyal state like Kentucky, Thomas explained, “I conceive I have only to do with those who can be put into the army.” Thomas believed that he lacked the authority to liberate enslaved women and children, but he also feared that women and children would deplete army resources. “It will not answer to take this class of slaves,” Thomas wrote, “as employment could not be obtained for them, and they would only be an expense to the Government.” If enslaved women remained at home, Thomas calculated, their slaveholders, rather than the army, would be responsible for feeding them. Moreover, they would be on hand to help harvest grain that would be essential to feeding Kentuckians and the Union army. Thomas insisted that he was dutifully following orders; if President Lincoln gave him the authority him to liberate women and children, Thomas declared himself “ready to obey his mandate.” From the perspective of Black recruits and their family members, however, Thomas’s policy seemed callous and inhumane. [3]

Thomas’s General Orders No. 24, issued on July 6, 1864, spelled out the US army’s new policy in Kentucky of discouraging enslaved women from coming to military outposts, while also threatening to return any women and children already behind army lines. “None but able-bodied men will be received,” Thomas declared. Women and children “will be encouraged to remain at their respective homes, where, under the State laws, their masters are bound to take care of them.” But Thomas went a step further. Women “who may have been received at Camp Nelson will be sent to their homes,” where they would be “required to assist in securing the crops, now suffering in many cases for the want of labor.” [4]

Some US officers in Kentucky protested that Thomas’s orders violated federal law. It was one thing to discourage enslaved women and children from coming, but it was another to actively return women and children who had already entered Camp Nelson. In that respect, Thomas’s General Orders No. 24 seemed like a clear violation of Congress’s revised Articles of War adopted in March 1862, which forbade Union military personnel from returning freedom seekers to bondage, on pain of dismissal from the service. At Paducah in western Kentucky, Col. H.W. Barry refused to obey Thomas’s order. “I cannot return to Slavery, the wives and Children of men, whome… fought so gallantly,” Barry declared. Thomas arrested the good colonel for defying his orders, though War Department officials back in Washington eventually sided with Barry and the enslaved women. At least in western Kentucky, US officials would not turn enslaved women and children out of army lines. [5]

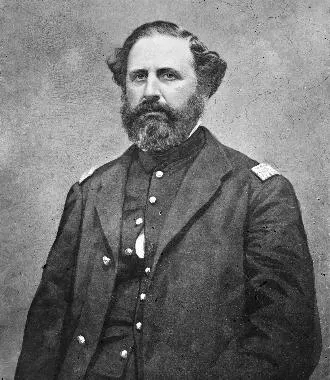

Brig. Gen. Speed Smith Fry, commandant of Camp Nelson (NPS)

No such protests came from Camp Nelson’s new commandant, Brig. Gen. Speed Smith Fry, a native Kentuckian who had already reached a general understanding with Thomas about the planned expulsion. The men agreed that they would select a date at which US forces would place all enslaved women and children outside the lines, furnishing them with just enough food to reach their slaveholders’ homes. Thomas even suggested that the US army give slaveholders advance notice of the expulsion so that they would be on hand to reclaim freedom seeking women and children. [6]

Impatient slaveholders were unwilling to wait for an official expulsion and showed up at Camp Nelson daily, using a combination of promises and threats to try to coerce freedom seekers back into slavery. “Their old owners came in carriages and on horseback every day to allure them by all kinds of promises and threats,” reported Sanitary Commission superintendent Thomas Butler. Sometimes slaveholders brought the wives of enslaved men along to camp, “and through them they attempt to bring back the servant and husband to slavery.” When such threats failed, slaveholders tried to sneak past camp guards and kidnap men and women back into slavery. [7]

Then suddenly and without warning, on Wednesday morning, November 23, 1864, enslaved women and children awoke to the sound of US soldiers gruffly shouting at them to leave camp. Within minutes, 400 enslaved women and children piled into six to eight large wagons and ominously trundled out of camp, to where they were not sure. [8]

To make matters worse, the morning was “bitter cold,” and “the wind was blowing hard,” recalled Joseph Miller of the 124th U.S. Colored Infantry. “Having had to leave much of our clothing when we left our master,” Miller explained, his wife Isabella and their four children were ”poorly clad” for such frigid temperatures–which hovered around 16 degrees Fahrenheit that morning. Miller was “certain that it would kill my sick child to take him out in the cold.” The soldier pleaded with one of the soldiers carrying out the expulsion. “I told him that my wife and children had no place to go and I told him that I was a soldier of the United States.” It “would be the death of my boy” to force him out into the biting cold without shelter. The guard was unmoved, however, and threatened to shoot Miller’s wife Isabella and their four children on the spot if they did not climb into an army wagon. [9]

Later that night, Miller caught up his family, taking shelter with other refugees in a ramshackle old meeting house near Nicholasville, six miles north of Camp Nelson. “The building was very cold having only one fire,” Miller explained. “My wife and children could not get near the fire, because of the number of colored people huddled together.” When Miller found Isabella, she and their children were “shivering with cold and famished with hunger.” His son had not survived the frigid cold. “My boy was dead,” Miller testified. “I Know he was Killed by exposure to the inclement weather.” The grieving father returned the next morning, where he “dug a grave myself and buried my own child.” [10]

AFTERMATH

The November 23 expulsion caused untold human suffering, but it also proved to be a critical turning point for the US army’s policy towards enslaved women and children in Kentucky. In the days that followed, Miller and other Black soldiers turned to sympathetic US officers in Camp Nelson to help share their harrowing ordeal with the public. Grief-stricken husbands and fathers dictated sworn affidavits before assistant quartermaster Capt. E.B.W. Restieaux. [11]

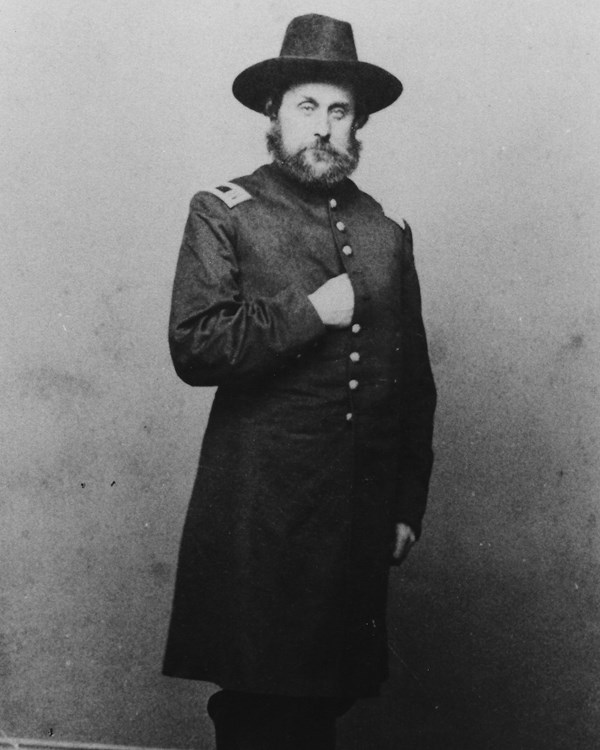

US army assistant quartermaster Capt. Theron E. Hall (NPS)

Another sympathetic quartermaster, Capt. Theron E. Hall, recognized that the tragedy could help rally public support behind the Black women and children, and perhaps even push Congress to take action to ensure that nothing of the sort ever happened again. “The slave Oligarchy,” Hall wrote, “put into my hands the most potent weapon I could use.” Hall wasted no time circulating the Black soldiers’ affidavits to major Northern newspapers and antislavery politicians. Almost overnight, the Camp Nelson expulsion became front-page news. “Cruel Treatment of the Wives and Children of U.S. Colored Soldiers,” read the headline of the New York Tribune on November 28. The paper’s gripping account of “a system of deliberate cruelty” shocked Northern readers. [12]

Official action soon followed. On November 27, General Burbridge directed General Fry to “not expell [sic] any Negro women or children from Camp Nelson.” Instead, Fry should “allow back all who have been turned out” and “if necessary erect buildings for them.” Several days later on December 2, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered that the quartermaster’s department construct permanent buildings to house Black women and children at Camp Nelson. “There will be much suffering among them this winter unless shelters are built and rations issued to them.” [13] Stanton’s order, writes historian Amy Murrell Taylor, “marked a significant blow to slavery in Kentucky, as it now opened the doors to any enslaved man, woman, or child wanting to enter the camp.” [14]

The expulsion also prodded Congressional lawmakers to action. Ohio senator Benjamin Wade read Joseph Miller’s affidavit into the senate record. Wade had visited Camp Nelson months earlier during the summer of 1864. Now on the Senate floor in January 1865, Wade roared that the expulsion had not only been inhumane, but it was against the US military’s interests to turn out Black women and children; doing so would discourage other enslaved Kentuckians from enlisting. “Colored men will not enlist while these things are allowed,” Wade argued. “They have the same feelings toward their wives and children that white men have… and where is the white man who would enlist in the Army of the United States and leave his wife and children subject tot the taunts, the insults, and the ignominy of a master.” [15]

The debate in Congress quickly crystallized around a bill that would free the wives and children of Black soldiers upon their enlistment. Congress approved the legislation on March 3, 1865. One week later on March 10, Stanton issued General Orders No. 10, declaring that for the purposes of enforcing the new law, the army would recognize marriages between enslaved people, even if Kentucky law did not. [16]

Back at Camp Nelson, Black families weathered the transition from slavery to freedom in what became known as the Refugees Home at Camp Nelson. (Continue reading part 3)

FURTHER READING

In recent years, historians have reconstructed Black families’ journeys to Camp Nelson and the details surrounding the infamous November 23, 1864 expulsion. A good starting place is Richard Sears’s Camp Nelson, Kentucky (2002), an edited collection of primary sources documenting the camp’s entire existence. The Freedmen and Southern Society Project’s Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation series 2 (The Black Military Experience), also features primary sources related to Black recruitment and Black family life at Camp Nelson. [17]

One of the first scholarly treatments of the expulsion, Victor Howard’s Black Liberation in Kentucky (1983), combs through army records to provide a detailed analysis of Black families’ fight for inclusion at Camp Nelson. [18] More recently, Amy Taylor’s essay, “How a Cold Snap in Kentucky Led to Freedom for Thousands” (2011) and her subsequent book Embattled Freedom (2018) show how the humanitarian crisis at Camp Nelson prodded congressional lawmakers to action. [19]

NOTES

[1] Affidavit of Patsey Leach, March 25, 1865, in Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 268-269.

[2] J. Bates Dickson to Capt. T.E. Hall, June 20, 1864, Lexington, Ky., in Sears, Camp Nelson, 72-73; Dickson to Sedgwick, June 30, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 87.

[3] OR, ser 3, v4, pt 1, 467, 474, [WEB]; Thomas to S.G. Hicks, July 17, 1864, in Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 260-261.

[4] OR, ser 3, v4, pt 1, 474, [WEB].

[5] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 260-262.

[6] Victor B. Howard, Black Liberation in Kentucky Emancipation and Freedom, 1862-1884 (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1983), 113-114; Order of Brig. Gen. Speed Smith Fry, July 6, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 93-94. On July 28, 1864, assistant adjutant general C.W. Foster replied to Thomas: “ Although the law prohibits the return of slaves to their owners by the military authorities, yet it does not provide for their reception and support in idleness at military camps.” See Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 263. Foster’s unhelpful reply did not address whether Thomas’s orders were in fact in violation of the revised Articles of War.

[7] Report of Butler, Sears, Camp Nelson, 83-84.

[8] Taylor, Embattled Freedom,201; Taylor, “How a Cold Snap in Kentucky Led to Freedom for Thousands: An Environmental Story of Emancipation,” 191-214, in Stephen Berry (ed.), Weirding the War: Stories from the Civil War’s Ragged Edges (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

[9] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 269-271; Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 201.

[10] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 269-271.

[11] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 269-271.; Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 202-203; Taylor, “How a Cold Snap.”

[12] Hall, quoted in Howard, Black Liberation in Kentucky, 116; Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 202-203; Taylor, “How a Cold Snap”; New York Tribune, quoted in Sears, Camp Nelson, 138.

[13] Burbridge to Fry, November 27, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 137; Townsend to Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army, December 2, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 146

[14] Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 203.

[15] Cong Globe, 38th Cong, 2nd sess., 160-162.

[16] Howard, Black Liberation in Kentucky, 79.

[17] Sears, Camp Nelson; Freedom ser. 2 (The Black Military Experience).

[18] Howard, Black Liberation in Kentucky, esp. chap. 8.

[19] Taylor, “How a Cold Snap”; Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 174-208.