DATELINE: NOVEMBER 1852, NEAR PETERSBURG, KY

Federal Hall plantation, photographed in 1938 (Cincinnati Enquirer, September 15, 1968, Newspapers.com)

Late one night, three enslaved people—two men and one woman, whose names were not recorded—quietly left Federal Hall, a plantation overlooking the Ohio River just northeast of Petersburg, Kentucky. Crossing the Ohio River into Indiana, their escape marked the latest in a series of group escapes that had slaveholders across northern Kentucky noticeably on edge. [1] Slaveholder Abraham Piatt’s subsequent efforts to recapture the three enslaved people uncovered an elaborate network of Black and white activists along the borderlands working to assist and shelter freedom seekers.

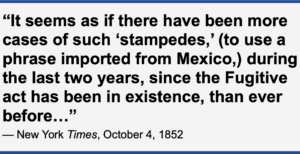

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

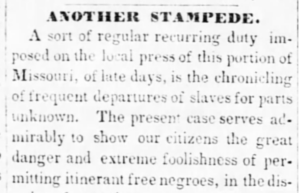

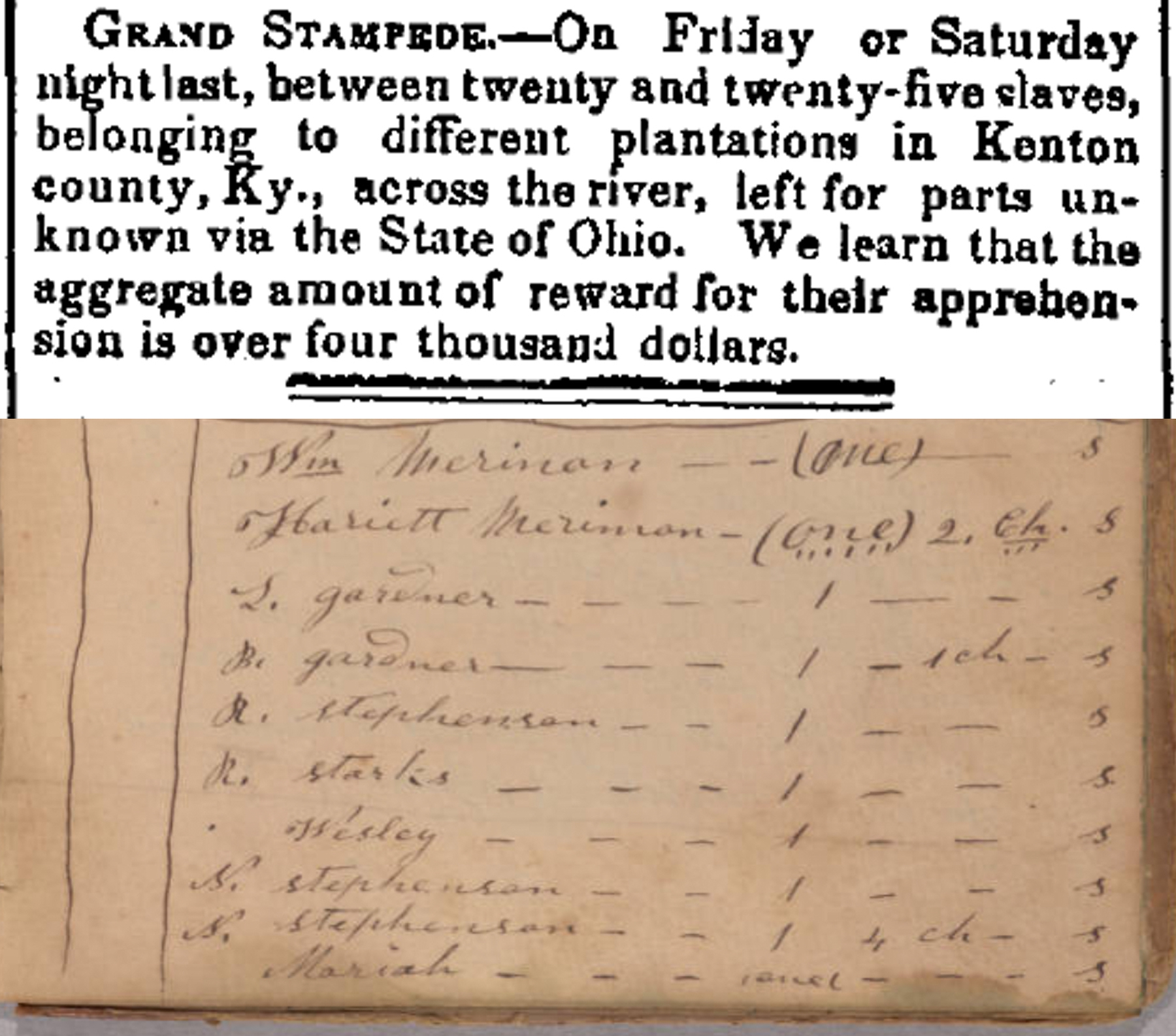

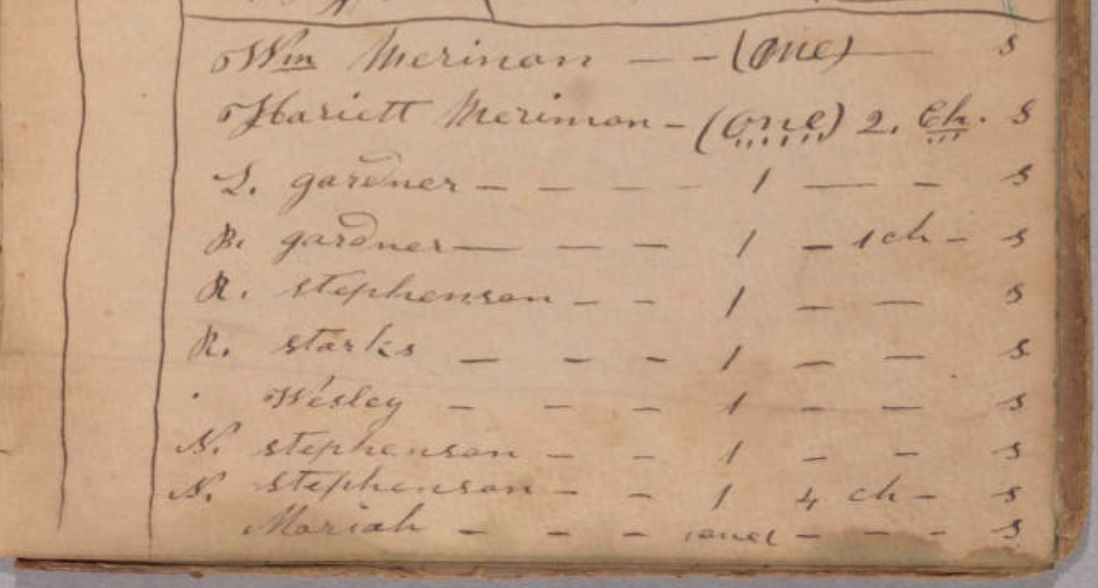

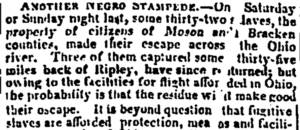

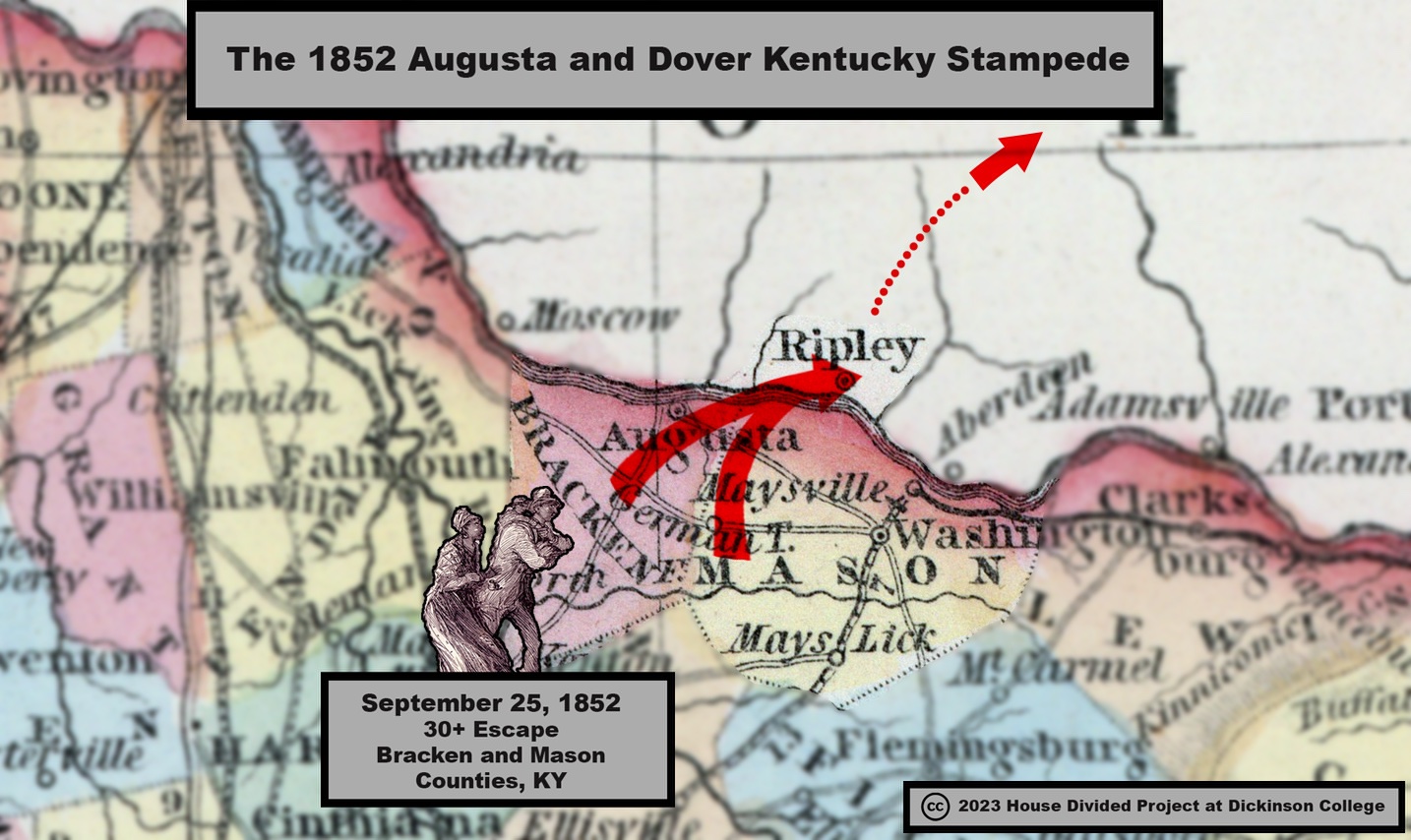

During the fall of 1852, newspaper reports described a wave of mass escapes or “stampedes” from the Kentucky borderlands, including one “stampede” of some 30 people from Augusta and Dover, Kentucky in late September. Contemporary observers understood the escape of the three freedom seekers as the latest episode of this growing “stampede” phenomenon. Reporting on the escape of “three negroes, belonging to Mr. Abraham Piatt, of this county,” the Boone County News warily observed: “This makes twenty-nine slaves that have ran away from this county since the first of September.” [2] White Kentuckian Jonas Crisler made a similar observation in a November 11 letter. “There has been at least 30 ran off this faul [sic],” Crisler wrote. “14 at and about Burlington and the rest about Petersburg. [from slaveholders] Abraham Piatts, Thomas Graves, and William Whittaker.” [3]

At least one newspaper directly linked the escape of the three freedom seekers to the term “stampede.” The Xenia, Ohio Torchlight described “a stampede among Kentucky slaves in which a number succeeded in effecting their escape,” before going into greater detail on the escape of the three freedom seekers from Piatt’s Federal Hall plantation. [4] The paper’s editors may have assumed that the three freedom seekers split off from a larger group of escapees, or simply may have used the term “stampede” to refer to the growing pattern of escapes collectively, rather than to a specific episode of mass flight.

MAIN NARRATIVE

White Kentuckians like Jonas Crisler were sure that the freedom seekers had help. In his November 11 letter bemoaning the escape of “at least 30” of “the most valuable” enslaved people in the county, Crisler aired his suspicions that a network of activists spanned the Ohio River to assist freedom seekers. “I have no doubt if things continue negroes slaves will be scarce neare [sic] the O. River,” Crisler added, “particularly if old Mat Bots and his clan continues their privilege they have had I believe they have been their pilots and is yet.” [5] It remains unclear exactly whom Crisler was referring to, but he clearly suspected that the freedom seekers had friends to help “pilot” them to freedom.

Crisler’s hunch was at least partly accurate. There was indeed an active Underground Railroad network across the river in Rising Sun, Indiana, spearheaded by a free Black family––the Barkshires. Originally enslaved in Boone County, the Barkshires moved across the Ohio River along with their slaveholder’s widow, Nancy Hawkins, during the mid-1830s. Once in Indiana, Mrs. Hawkins took the precaution of formally manumitting (or freeing) the Barkshire family: Samuel Barkshire (already freed in Kentucky in 1833), his wife Harriet (freed in 1838) and their children Arthur, Garrett, Matilda, Emily, Woodford, and Minerva (all formally freed in 1848). [6]

From their new home in Rising Sun, the Barkshires led a highly active Underground Railroad network. Kentucky freedom seeker John White told an abolitionist that he escaped during the 1840s with help from “his colored friends, at Rising Sun.” Several years later, when White crossed back into Kentucky to help his wife and children escape, his “colored friends” advised White to “row across to a point above Rising Sun,” where they would meet him with a wagon ready to escort him and his family to freedom. White’s attempt to rescue his family came up tragically short, but his multiple interactions with Black activists in Rising Sun point to the existence of a coordinated Underground Railroad network along the banks of the Ohio River. [7]

The people enslaved on the Piatt’s Federal Hall plantation were aware of this Underground Railroad network in Rising Sun. At least one person enslaved by the Piatts, the family’s coachman (whose name was not recorded) reportedly escaped with the help of Woodford Barkshire, the family’s youngest son. Enraged, the Piatts organized a posse, which traced the missing coachman “across the Ohio [River] and into Indiana about five miles from Barkshire’s depot.” The Piatts blamed Woodford Barkshire for the escape of their enslaved coachman, but were never able to recapture the coachman. [8]

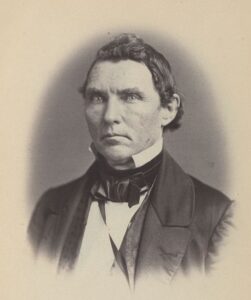

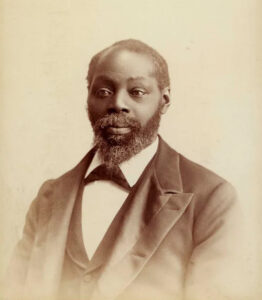

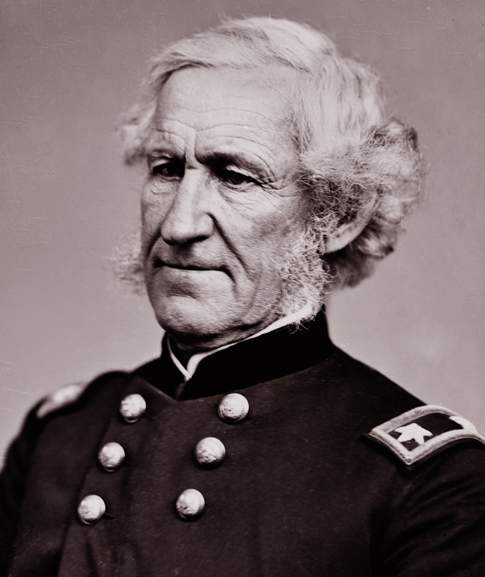

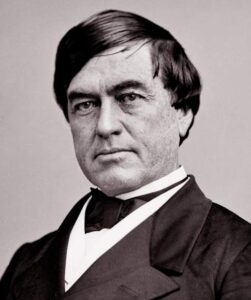

Levi Coffin (House Divided Project)

It is unclear whether the three freedom seekers who escaped in November 1852 received assistance from the Barkshires or other free Blacks at Rising Sun, but evidence suggests they did obtain help from Underground Railroad activists in Cincinnati. One account (a recollection penned in 1891) places the freedom seekers at the Cincinnati home of prominent white abolitionist Levi Coffin. Together with William H. Brisbane, a former South Carolina slaveholder-turned-abolitionist, Coffin “put them on a train on the old Mad River & Lake Erie Railroad, and paid their fare to Sandusky City.” [9] Although Coffin did not describe this specific escape in his post-Civil War memoir, the abolitionist related that he “often raised money, bought tickets, and forwarded the fugitives by rail to Detroit, Sandusky, or some other point on the lakes, when it was not likely that hunters were ahead of them.” [10]

Coffin may have thought the coast was clear, but the freedom seekers were not yet clear of the Piatts. Soon after the freedom seekers left Cincinnati aboard the Mad River & Lake Erie Railroad, they crossed paths with Donn Piatt––the nephew of their slaveholder Abraham Piatt. Much about the encounter on the moving rail car remains unclear. It may well have been sheer coincidence that put Donn Piatt on the same northbound train as the enslaved people who had just escaped from his uncle’s Kentucky plantation. But at least one source suggests otherwise. An 1891 recollection, penned by an abolitionist who later assisted the freedom seekers, alleged that the Kentucky Piatts telegraphed ahead to their Ohio relatives “to watch the trains” for the three enslaved people. [11]

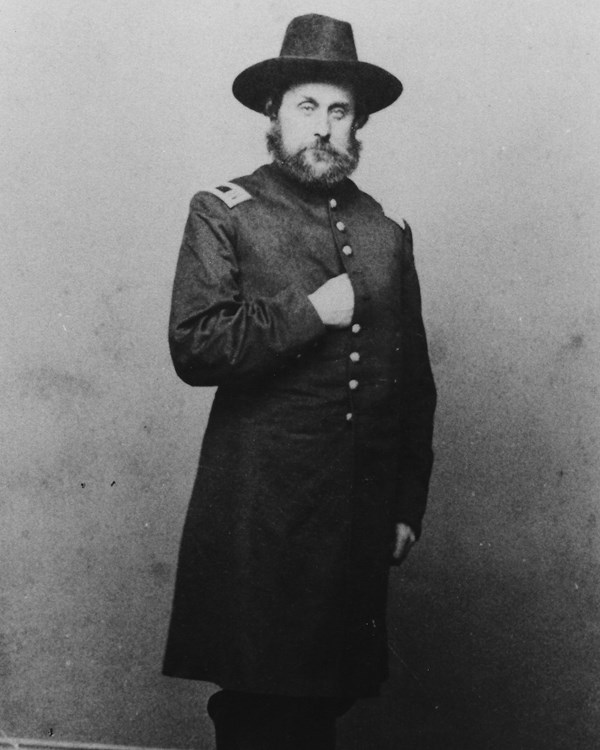

An 1854 painting depicting Donn Piatt (Charles Grant Miller, Donn Piatt: His Work and Ways, 1893, Internet Archive)

On the surface, Donn Piatt was an odd choice to “watch the trains” for the freedom seekers. Born in Ohio in 1819, Piatt was a lawyer and journalist whose antislavery sympathies were publicly known. As his biographer notes, Piatt stood guard outside the Cincinnati office of abolitionist James Birney’s newspaper, the Philanthropist, to defend the paper from a proslavery mob in 1836. A decade later, Piatt was the driving force behind a petition to Congress “remonstrating against the admission of Texas or any other State into the Union as a slave State.” Two years later in 1848, Piatt doubled-down on his opposition to new slaves states when he joined the Free Soil Party, an offshoot of the Democratic Party which protested the expansion of slavery into the western territories. [12]

Crucially, Piatt’s political opposition to the expansion of slavery did not necessarily translate into a belief in racial equality or a willingness to help enslaved freedom seekers. Rather, all the evidence strongly points to the conclusion that Donn Piatt was determined to return the three freedom seekers to his slaveholding uncle. [13] Aboard the train from Cincinnati, Piatt approached the freedom seekers with a proposition. He “told them that his father who resides near West Liberty, was in want of laborers.” If “they would stop with him” and exit the train at West Liberty, Piatt promised steady work. Even better, Piatt and his father would purchase their freedom. [14] It remains unclear how much Piatt actually divulged during this initial interaction. Did he reveal his connection to their enslaver, his uncle? Did the freedom seekers recognize Piatt? Whatever the circumstances, Piatt’s ploy worked. Through some mix of persuasion, intimidation, or perhaps a little of both, the three enslaved Kentuckians got off the train with Piatt at West Liberty, Ohio.

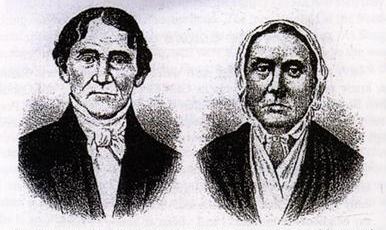

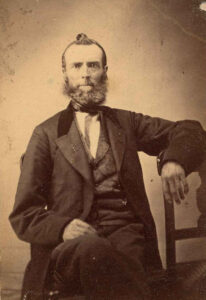

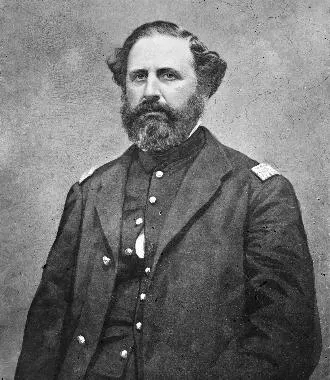

Benjamin McCullough Piatt, the father of Donn Piatt and older brother of slaveholder Abraham Piatt (Find-A-Grave)

Soon after the encounter, on Thursday afternoon, November 11, 1852, Donn Piatt’s father, the retired judge Benjamin McCullough Piatt, telegraphed his slaveholding brother Abraham that they had apprehended the freedom seekers. Abraham and the Kentucky Piatts started in pursuit. [15]

When the free Black community near West Liberty learned of the arrangement the Piatts had struck with the freedom seekers, they sprung into action. Local Black residents “understood the character of the Piatts,” and recognized that the freedom seekers were in grave danger so long as they stayed with the Piatts. Free Black Oliver Ash was the first to discover that the freedom seekers were with the Piatts. Ash attempted to speak with the freedom seekers, but the Piatts—probably fearing what Ash would say—would not allow the local Black activist “to get access to them.” Undeterred, Ash turned to two sympathetic white lawyers in nearby Bellefontaine, William H. West and James Walker. Upon Ash’s request, the two attorneys filed a writ of habeas corpus before the local probate court. The writ required “old [Benjamin] Piatt to bring them before a judge at Bell[e]fontaine, and to show by what authority he held them.” [16]

Aware that their Kentucky relatives were already en route, Benjamin and Donn Piatt attempted to stall the proceedings. “The Piatts present attempted by all means within their power, to delay proceedings until the arrival of their Kentucky relatives on the incoming train due within a very few hours,” recalled Robert T. Kennedy, then a 12-year-old boy who witnessed the affair. Attorney William West similarly remembered how Benjamin Piatt “resisted the discharge of the negroes and talked against time,” desperately trying to drag out the hearing. Despite the Piatts’ delay tactics, the case moved swiftly and Judge Ezra Bennett—whose sympathies seemed to lie with the freedom seekers—pronounced them “free to go where they pleased.” [17]

Even so, the local Black community recognized that the Kentucky Piatts might arrive at any moment. Antislavery activists rushed the three freedom seekers out of the hearing room “to a carriage already in waiting,” driven by Black barber William E. Johnson, a leading activist in Bellefontaine’s African American community. Twelve-year-old Robert Kennedy, together with other young “abolition boys” and interested onlookers, watched Johnson drive the freedom seekers northward. “I can see that carriage now,” Kennedy recalled in 1893, “with its closely drawn curtains and its two horses, going at the top of their speed, moving up the hill and disappearing out of sight toward that Mecca of all escaping slaves the ‘Quaker Bottoms.’” [18]

AFTERMATH

Actually, the freedom seekers would not find refuge with Quakers, but with college students. Johnson drove the three freedom seekers about eight miles north to the village of Northwood. There, the freedom seekers spent the next two weeks with the faculty and students of Geneva College, a small Presbyterian school. (The school still exists today, but at a new location in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania). Two Geneva students—R.H. Johnston and Robert Archibald McAyeal—each wrote accounts during the 1890s detailing how they provided sanctuary to the freedom seekers on or near campus. Johnston, son of the college’s founder, recalled that some of the freedom seekers stayed with his father, while others concealed themselves in a nearby cave. Protecting the freedom seekers were “students well armed with revolvers and double barreled shot guns.” [19]

After about two weeks, a group of students that included McAyeal, J.M. Elder, J.S.T. Milligan, D.J. Shaw, and J.R. Johnston took out “a large covered wagon as though going hunting.” “We assumed the appearance of a hunting party, each one carrying a rile,” recalled McAyeal. Instead of going hunting, the students transported the freedom seekers north through Kenton, Findlay, Perrysburg and then east to Sandusky—“a two days’ and part of two nights’ drive,” McAyeal remembered. [20]

Advertisement for Capt. Sylvester Atwood’s steamboat, the Arrow. (Sandusky, OH Register, November 22, 1852, Newspapers.com)

At Sandusky, the freedom seekers boarded Capt. Sylvester Atwood’s steamboat, the Arrow. Advertised as the “Cheapest, Quickest, and Most Pleasant Route” to Chicago, Atwood’s steamer left Sandusky daily at 6:30 p.m. [21] As the Geneva students surely knew, Atwood was not only a skilled steamboat captain, but a reliable friend to enslaved people. Freedom seeker William Edwards, who escaped aboard the Arrow in 1848, had witnessed Atwood’s antislavery principles in action. “In crossing from Sandu[s]ky to Amherstburg [Canada] there were some slave holders on the boat,” Edwards recalled. The enslavers offered Atwood $50 to land at Detroit first, so that they could reenslave Edwards, but Atwood “said he wouldn’t for $500.” [22]

By 1852, slaveholders were also growing wise to Atwood’s Underground Railroad connections. The exact same month that Atwood helped the three freedom seekers from Boone County, another slaveholder sued Atwood to “recover the value of eight salves that took passage on that boat to Detroit or Canada.” [23]

The pending lawsuit hanging over Atwood’s head did not deter him from helping the three freedom seekers. One of the Geneva students joined the freedom seekers aboard the Arrow “and saw them safely landed at Malden, Canada,” near Amherstburg, “where they were safe under the British flag.” [24]

FURTHER READING

The most detailed contemporary account of the escape and subsequent court case, “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” was originally published by the Xenia, Ohio Torchlight and widely reprinted by antislavery newspapers. [25]

In 1888, Donn Piatt published a short story about the escape entitled “Old Shack,” which notably softened the reality of his family’s ties to slavery. Piatt based the story around an old enslaved man named “Shack,” who claimed to have been his grandfather’s “body-servant during the Revolution and through the war of ’12.” According to Piatt, Shack one day appeared at his father’s West Liberty, Ohio home “at the head of about twenty colored men, women, and children, escaped salves from my grandfather’s farm, Federal Hall, Boone County, Kentucky.” Inflating the number of freedom seekers from three (as all contemporary accounts stated) to 20, Piatt also conveniently elided his own role in redirecting the freedom seekers off the train and to his father’s home. Moreover, Piatt maintained that his father, Benjamin, “was perfectly amazed at their appearance, for slavery at Federal Hall, as he remembered it, was purely nominal. The negroes worked when they felt like it, which was very seldom.” Piatt claimed that when his father notified the Kentucky relatives “that his negroes were at [the family home called] Macochee,” his grandfather, Col. Jacob Piatt (who had died nearly two decades earlier in 1834) “replied by post, in a letter that cost twenty-five cents, that he felt very much relieved at their going, and hoped steps might be taken to prevent their return,” denouncing the enslaved people’s “laziness, lying, and theft.” As contemporary sources make clear, the Kentucky Piatts actively pursued the three enslaved people. [26]

During the 1890s, historian Wilbur Siebert collected accounts from antislavery lawyer William H. West and Robert Kennedy, who shed light on the response of Bellefontaine’s Black community and the habeas corpus hearing. [27]

[1] Boone County News, quoted in Louisville (KY) Courier, November 13, 1852

[2] Boone County News, quoted in Louisville (KY) Courier, November 13, 1852

[3] Jonas Crisler letter, November 11, 1852, Crisler Family Papers, Kentucky Historical Society, excerpted at African Americans on the Kentucky Borderlands, [WEB].

[4] “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” Ravenna (OH) Ohio Star, December 1, 1852

[5] Jonas Crisler letter, November 11, 1852, Crisler Family Papers, Kentucky Historical Society, excerpted at African Americans on the Kentucky Borderlands, [WEB].

[6] Hillary Delaney, “The Underground Railroad at Slavery’s Banks: An Unlikely Alliance,” Untold Indiana (October 4, 2018), [WEB].

[7] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, The Reputed President of the Underground Railroad (Cincinnati, OH: Western Tract Society, 1876), 216-222, [WEB].

[8] “Underground Railroad: More Western Memories––How Slaves Were Harbored and Forwarded to Canada Before the War,” Brooklyn (NY) Eagle, May 24, 1887.

[9] “A Reminiscence of the Slavery Era,” Boston (MA) Daily Traveller, December 5, 1891

[10] Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, 594, [WEB].

[11] Henderson (KY) Democratic Banner, “R[u]naway Slaves,” November 25, 1852; “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” Ravenna (OH) Ohio Star, December 1, 1852; Boston Travleler

[12] Peter Bridges, Donn Piatt: Gadfly of the Gilded Age (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2012), 16-23.

[13] Piatt’s biographer, Peter Bridges, casts doubt that Donn Piatt was the family member aboard the train who encountered the freedom seekers. Bridges suggests that Piatt’s antislavery background made it unlikely he would take such action. Moreover, Bridges points out that a widely reprinted 1852 article identifies the culprit as “one Don Piatt, an ex judge of the Hamilton Common Pleas Court.” Piatt’s father, Benjamin McCullough Piatt, was a former judge at the time; whereas Donn Piatt “was still on the bench at Cincinnati” in 1852. See Bridges, Donn Piatt, 22-24. However, the recollection of antislavery lawyer William H. West clearly identifies Donn Piatt, not his father, as the person who first encountered the freedom seekers. See Interview with William H. West, August 11, 1894, Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]

[14] “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” Ravenna (OH) Ohio Star, December 1, 1852

[15] Boone County News, quoted in Louisville (KY) Courier, November 13, 1852

[16] “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” Ravenna (OH) Ohio Star, December 1, 1852; Interview with William H. West, August 11, 1894, Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]

[17] “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” Ravenna (OH) Ohio Star, December 1, 1852; Robert T. Kennedy to Wilbur Siebert, January 22, 1893, Bellefontaine, Oh., Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]; Interview with William H. West, August 11, 1894, Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]

[18] Interview with William H. West, August 11, 1894, Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]; Robert T. Kennedy to Wilbur Siebert, January 22, 1893, Bellefontaine, Oh., Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]

[19] RH Johnston 1894; “A Reminiscence of the Slavery Era,” Boston (MA) Daily Traveller, December 5, 1891. Especial thanks to Kae Kirkwood, archivist at Geneva College, for her help identifying Richard Archibald McAyeal (Class of 1853) as the likely author of the 1891 reminiscence. (The author of the 1891 article identified himself as a student at Geneva in 1852 but signed his name simply “R.A.M.”)

[20] “A Reminiscence of the Slavery Era,” Boston (MA) Daily Traveller, December 5, 1891; RH Johnston 1894]

[21] “Cheapest, Quickest, and Most Pleasant Route,” Sandusky (OH) Register, November 22, 1852

[22] Statement of Dr. William Edwards of Amherstburg, Ontario, August 3, 1896, Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB].

[23] Marysville (OH) Tribune, November 17, 1852. The charges may have been dropped. I have been unable to find any outcome of this case.

[24] “A Reminiscence of the Slavery Era,” Boston (MA) Daily Traveller, December 5, 1891

[25] “Fugitive Slave Case in one Chapter,” Ravenna (OH) Ohio Star, December 1, 1852

[26] Donn Piatt, The Lone Grave of the Shenandoah, And Other Tales (Chicago, New York, and San Francisco: Belford, Clarke & Co., 1888), 81-85, [WEB].

[27] Robert T. Kennedy to Wilbur Siebert, January 22, 1893, Bellefontaine, Oh., Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]; Interview with William H. West, August 11, 1894, Wilbur Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]

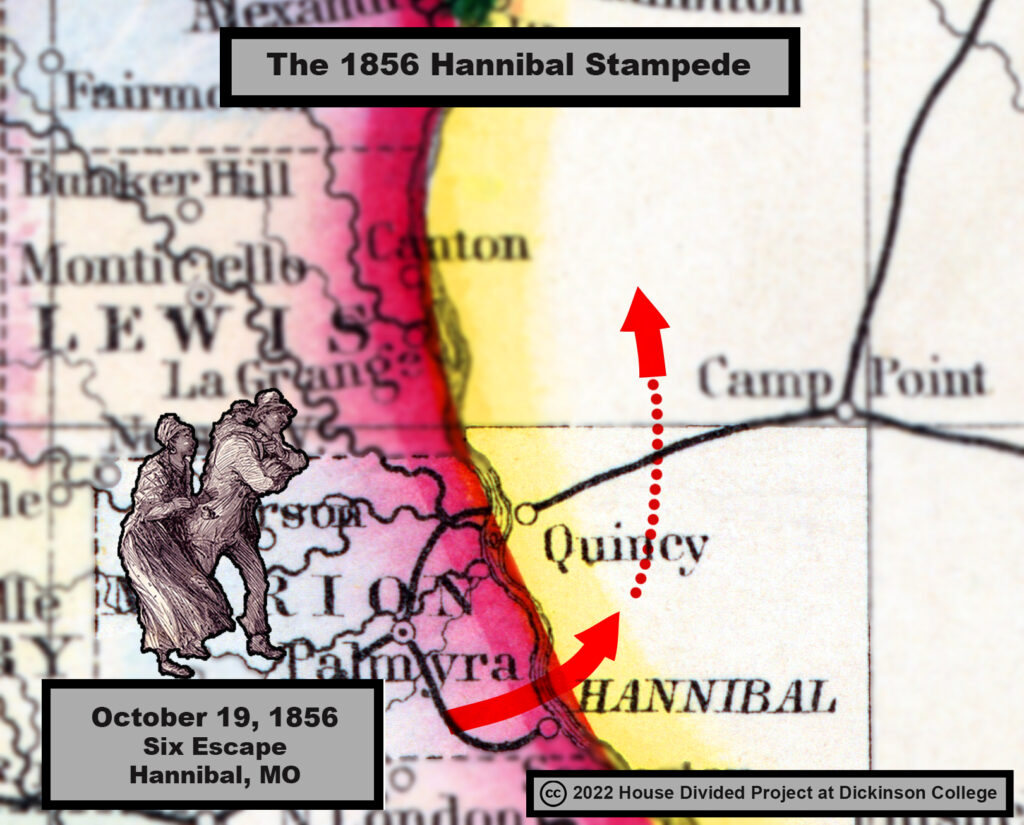

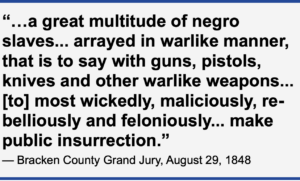

To slaveholders, the mass escape had looked alarmingly like a mobile insurrection. Decades later, freedom seeker Harry Slaughter would insist the stampede was not an insurrection, although he acknowledged the freedom seekers’ intention to defend themselves with force if necessary. “The movement was afterwards referred to as an ‘insurrection,’ but it was misnamed,” Slaughter explained. “We did not intend to fight unless attempts were made to capture us, but we pledged ourselves that if we were overtaken by white men and they made an effort to capture us we would fight as long as possible.” Slaughter’s distinction between defensive and offensive violence did not resonate with white Kentuckians. The criminal charges eventually brought against Doyle and Slaughter accused them of leading “a great multitude of negro slaves… arrayed in warlike manner, that is to say with guns, pistols, knives and other warlike weapons… [to] most wickedly, maliciously, rebelliously and feloniously… make public insurrection.” [12] In fact, the most enduring impact of the escape may well have been to help define the new “slave stampede” metaphor as a form of mobile insurrection.

To slaveholders, the mass escape had looked alarmingly like a mobile insurrection. Decades later, freedom seeker Harry Slaughter would insist the stampede was not an insurrection, although he acknowledged the freedom seekers’ intention to defend themselves with force if necessary. “The movement was afterwards referred to as an ‘insurrection,’ but it was misnamed,” Slaughter explained. “We did not intend to fight unless attempts were made to capture us, but we pledged ourselves that if we were overtaken by white men and they made an effort to capture us we would fight as long as possible.” Slaughter’s distinction between defensive and offensive violence did not resonate with white Kentuckians. The criminal charges eventually brought against Doyle and Slaughter accused them of leading “a great multitude of negro slaves… arrayed in warlike manner, that is to say with guns, pistols, knives and other warlike weapons… [to] most wickedly, maliciously, rebelliously and feloniously… make public insurrection.” [12] In fact, the most enduring impact of the escape may well have been to help define the new “slave stampede” metaphor as a form of mobile insurrection.