DATELINE: ST. LOUIS, OCTOBER 22, 1854

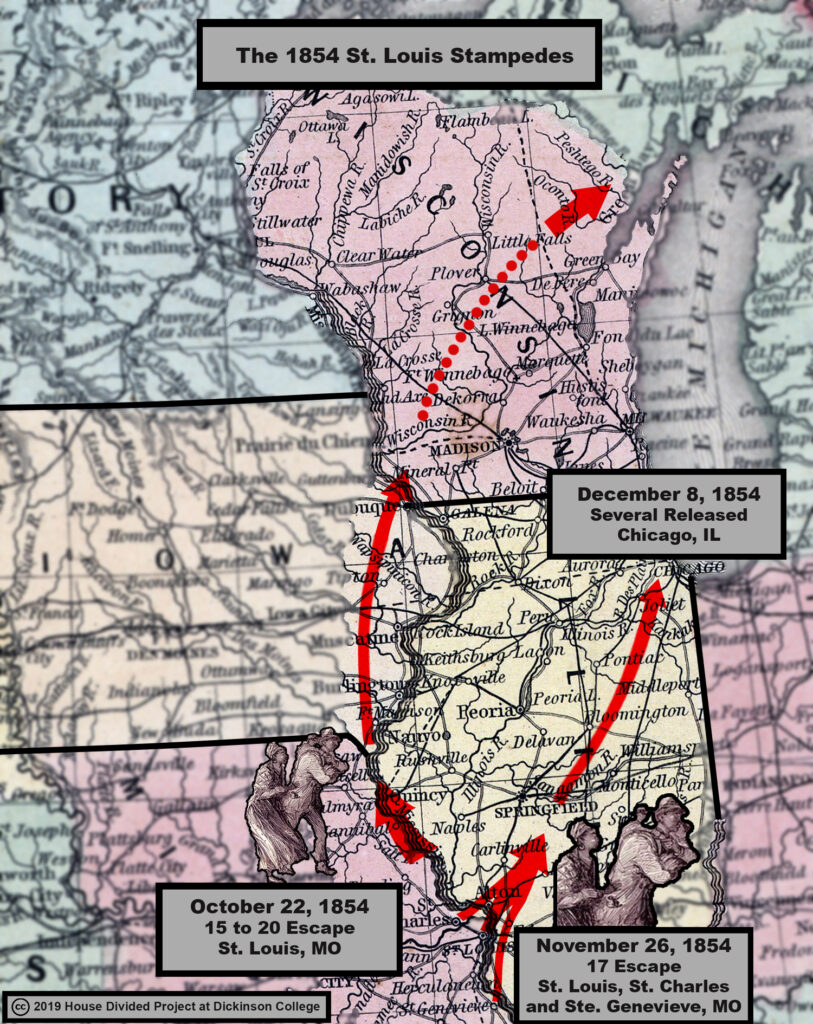

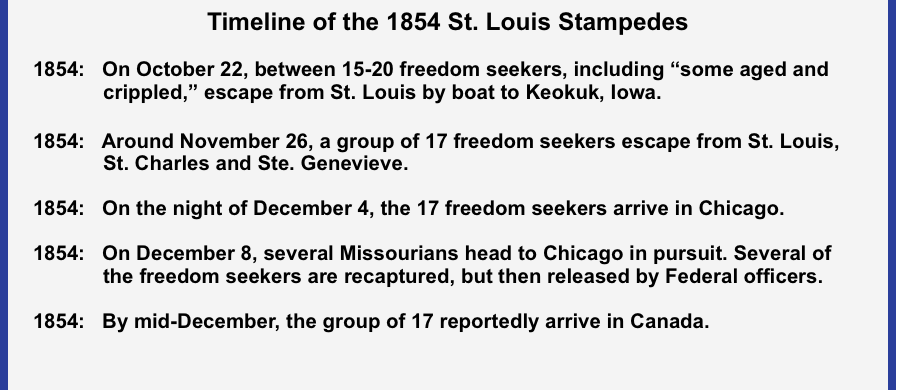

Around midnight on Sunday, October 22, 1854, a group of “fifteen or twenty” enslaved Missourians launched their bid for freedom. Having received permission from their slaveholders––four of St. Louis’ most prominent citizens and merchants––to attend church services, they seized the opportunity to escape. Yet this was no ordinary group of freedom seekers. The escapees included “a number of women and children,” as well as “some aged and crippled.” Given the group’s assortment of young and elderly members, it seemed “extremely probable,” in the view of one St. Louis newspaper, “that all, or a majority of them, will be retaken.” [1]

Scarcely a month later, around Sunday, November 26, another series of escapes once again sent shockwaves through St. Louis’ slaveholding class. Ten more freedom seekers set out from St. Louis, crossing paths with four enslaved people from nearby St. Charles, and three other runaways from Ste. Genevieve, farther to the south. “No traces have as yet been discovered of the fugitives,” reported a baffled St. Louis editor, who could only conclude that the freedom seekers were “under the hands of the most skillful guides.” [2] The St. Louis “stampedes” for freedom both confounded and unsettled slaveholders, while also revealing the tenuous nature of slavery in the border South.

To view an interactive map of this stampede, check out our StorymapJS version at Knight Lab

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

Contemporary newspapers used the term “stampede” in describing both the October and November escapes. Most quoted initial reports from the St. Louis Democrat, which ran an article headlined “Stampede Among the Africans” in late October 1854, and a column entitled “Another Slave Stampede,” following the second group escape. The Democrat‘s reports––with “stampede” in the title––were reprinted by Northern serials such as the Akron, Ohio Summit County Beacon and the New York-based National Anti-Slavery Standard. [3]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Missouri merchant, fur trader and slaveholder Pierre Chouteau, Jr. (South Dakota Historical Society)

The names, ages and genders of the “fifteen or twenty” freedom seekers who departed St. Louis on October 22 are unknown. However, the escapees were claimed by a cadre of prominent St. Louis merchants and slaveholders, who offered “heavy rewards” for their return. Three were held by 65-year-old Pierre Chouteau, Jr., the wealthiest man in St. Louis and head of a prominent Francophone family. Chouteau was a fur trader and merchant, claiming a total of 15 enslaved people in 1850. Yet his extended family counted over 100 enslaved people among their holdings, along with a reputation for mercilessly pursuing runaway slaves. Chouteau was also the father-in-law of John Sanford, who later became known for contesting Dred Scott‘s freedom suit. Among the three escapees claimed by Chouteau was a “young woman, nearly white,” whom the Chicago Democrat later alleged was his “natural daughter.” According to the paper, she was “about to be sold for the purposes of prostitution to a southern man” which prompted her escape. [4]

Three of the freedom seekers were claimed by 63-year-old Emmanuel Block, a well-to-do Austrian emigrant and neighbor of Chouteau. Block held some 24 enslaved people in 1850, ranging in age from a 50 year-old man to a 4 month-old infant. Yet October 1854 was not the first time Block was forced to grapple with his slaves’ innate desire for freedom. Back in 1850, Block had informed census takers that two of his enslaved people were “fugitives from the state.” Extremely wealthy nonetheless, by the time of the 1860 Census, Block was worth $50,000 (still well shy of Chouteau, who was worth $400,000). [5] Six more escapees were claimed by Edward James Gay, a 38-year-old merchant and grocer, while another “three or four” were held by cabinetmaker William H. Merritt, part of the St. Louis furniture firm Wayne & Merritt. [6]

St. Louis merchant Edward James Gay (Find A Grave)

Setting out around midnight on Sunday, October 22, the freedom seekers crossed the Mississippi River and reached Illinoistown (modern day East St. Louis, IL). When Chouteau, Block and the other slaveholders learned of the escape, they quickly dispatched St. Louis officers to recapture the freedom seekers, offering sizable rewards for their return. Yet while the officers scoured the vicinity, reasonably confident that they could overtake a group partly comprised of women, young children and “aged and crippled,” the escapees had other plans in mind. [7]

Rather than travel by land, the large group clambered on board a boat at Illinoistown, reportedly concealing themselves in “boxes marked as goods.” They traveled north up the river to Keokuk, Iowa, where they disembarked and reportedly continued by land to Wisconsin and from there to Canada. The runaways’ decision to travel first to Keokuk was no accident. By the 1850s, the bustling riverside city was fast becoming a regular stop for enslaved people striking out for their freedom. Around one year earlier, Charlotta Pyles and her extended family, numbering around 20, had fled slavery in Kentucky, traveling overland by way of St. Louis, crossing the Missouri River and eventually arriving in Keokuk. Pyles and her relatives had received assistance from a white guide named Nat Stone, who was no abolitionist, but agreed to lead the party in exchange for a hefty fee. Whether abolitionists or opportunists, white men like Stone were exactly the sort of outside actors whom St. Louis slaveholders feared the most. [8]

Although it remains unclear whether the latest group of runaways also obtained assistance, most slaveholders assumed they had. The St. Louis Democrat spoke for much of St. Louis’ slaveholding elite when it contended that the escapees must have acted “by the advice and control of the numerous underground railroad agents that infest our city.” The editors of the Republican agreed but pointed the finger at another white man named Davis. Just a few days earlier, authorities had arrested Davis after he “walked boldly” into a public establishment with a Black friend and “declared his Abolition sentiments.” The Republican claimed that the same man had later been caught forging passes for enslaved people, and the paper’s proslavery editor urged that “the authorities of our city cannot be too particular in watching and punishing the emissaries of Abolitionism, both black and white, that are known to be in our midst.” [9]

City authorities were in fact clamping down on free African Americans in October 1854, after what appears to have been an internal debate over strategy within the Black community spilled out into the open. Much of the controversy centered around Hiram Revels, the newly installed preacher at the AME church on the corner of Eleventh and Green streets who later would become the nation’s first-ever Black U.S. senator. Ever since he had arrived in St. Louis by way of Ohio in 1853, Revels’s blunt sermons had split his congregation. Contemporary reports do not identify what about Revels’s preaching was so polarizing, but Revels himself later recalled that he “sedulously refrained from doing anything that would incite slaves to run away from their masters… it being understood that my object was to preach the gospel to them, and improve their moral and spiritual condition even slave holders were tolerant of me.” Revels defended his approach as a matter self-preservation. Missouri’s strict Black codes required free African Americans to have a license to reside in the state, and Revels (who did not have a license) feared that any bold antislavery pronouncements on his part would attract the attention of city police. [10]

Revels’s conservatism may have clashed with members of his congregation who wanted to adopt a more confrontational tone, and perhaps with enslaved congregants busy plotting their own escapes. Tensions reached a fever pitch on Wednesday night, October 18 (just days before the October 22 stampede), when churchgoers interrupted Revels’s sermon, knocked him out of the pulpit, and engaged in a “skirmish of about fifteen minutes duration.” Some angry church members went straight to city authorities and informed on fellow free Blacks who were in the state without license, landing Revels and at least 14 others in prison. [11] Whether the dispute between Revels and his congregants had anything to do with the upcoming escape remains unclear, but what is clear is that the October 22 stampede took place amid heightened tensions within the Black community and as city police ramped up surveillance over the city’s free Black population.

St. Louis slaveholders were still reeling from the October 22 escape when another “stampede” of “some seventeen slaves” occurred over the weekend of Friday November 24 – Sunday, November 26. Coming as it did on the heels of the successful October stampede, the two large escape efforts may have been connected. Regardless, nervous St. Louis slaveholders viewed it as the continuation of what was in their eyes a disturbing trend of group escapes. [12]

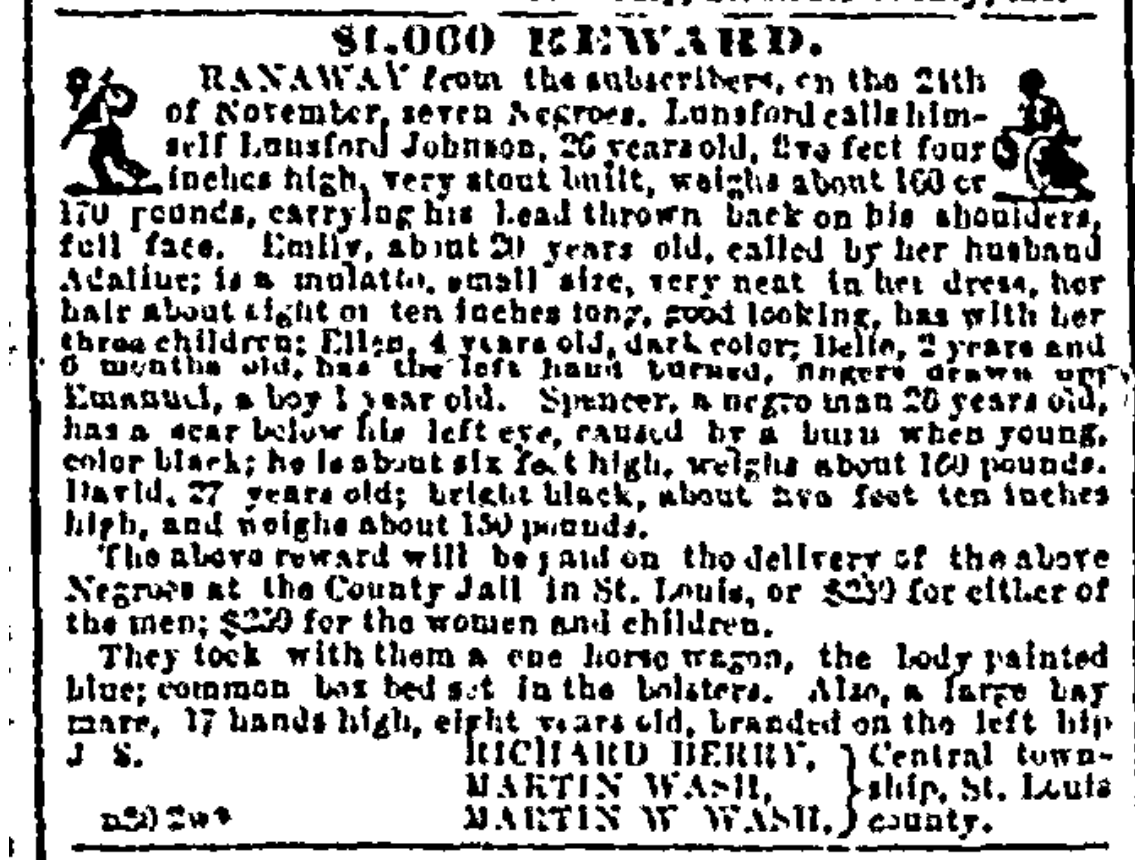

Slaveholders Richard Berry and Martin Wash posted a $1,000 reward for the recapture of the St. Louis freedom seekers. (St. Louis MO Republican, December 6, 1854, GenealogyBank)

The 17 freedom seekers who set out in late November included 10 enslaved people held in St. Louis, four from nearby St. Charles and three others from Ste. Genevieve. Of the group that escaped from St. Louis on Friday night, November 24, the names of seven individuals survive––26-year-old Lunsford Johnson, 20-year-old Emily (also called Adaline), and her three young children, four-year-old Ellen, two-year-old Belle, and one-year-old Edmund. Two other escapees can also be identified, a 26-year-old man named Spencer and a 27-year-old male named David. Lunsford, Emily and her three children were apparently held by a 34-year-old farmer named Richard Berry. Originally from Virginia, in 1850 Berry had laid claim to three enslaved people––a 22-year-old black male (possibly Lunsford), a 15-year-old mulatto female (possibly Emily) and a one-year-old male child. Later that year, in September 1850, he purchased two more enslaved people at his late father’s estate sale, paying $400 for 9-year-old Gilbert, and $420 for 7-year-old Jesse. Berry reportedly held a total of six enslaved people come November 1854. [10] Three other escapees were claimed by a “Mrs. Smith” of St. Louis, and two (likely Spencer and David) by Martin Wash, a 67-year-old farmer who, like Berry, was born in Virginia. Wash held 10 enslaved people in 1850, ranging in age from a 60-year-old black female to a two-year-old infant. [13]

Unlike the freedom seekers who had escaped in October, the escapees in late November opted to travel by land, heading towards Chicago. To effect their escape from St. Louis, Lunsford Johnson, David, Spencer, and Emily, along with her three young children made use of a blue-painted “one horse wagon.” We do not know the precise details of how or when the other ten freedom seekers fled bondage. According to one newspaper account, the 17 escapees from St. Louis, St. Charles and Ste. Genevieve set off in five separate groups, and “accidentally met on the road” to Chicago. Disgruntled slaveholders Richard Berry and Martin Wash posted a joint $1,000 reward for their recapture. Over the following weeks, the editors at the St. Louis Democrat and slaveholder Richard Berry were busily scanning Chicago papers for any reference to the escapees––which they found in the December 5 edition of the Chicago Tribune. The paper announced that “seventeen passengers arrived in our city by the underground railroad” on the night of Monday, December 4. While declaring that the freedom seekers were “immediately forwarded to ‘the land of the free'” (a reference to Canada), Berry was not convinced. He set out for Chicago immediately. [14]

Berry and three other unidentified Missourians travelled north to Chicago, arriving on Friday, December 8. They headed straight for the office of U.S. Commissioner John A. Bross––a federal official tasked with enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850––who issued warrants of arrest for the seventeen freedom seekers. U.S. District Attorney Thomas Hoyne dispatched his deputy marshal to aid Berry in recovering the escapees. Yet attempts to enforce the 1850 law in Chicago had a fraught history––the city’s African American community had routinely thwarted efforts to recapture escaped slaves since the law’s passage in September 1850. The anti-slavery community relied on both a covert vigilance network and open legal pressure to deter slave catchers. [15]

Although the warrants had been made out, Berry soon discovered that recapturing freedom seekers in Chicago was no simple task. Early on the morning of December 8, Berry spotted one of the male freedom seekers at the McCardel House Hotel on Dearborn Street. Berry “pointed out” the escapee to the deputy marshal, but the federal officer refused to seize him, “fearful of his life if he attempted the task alone.” Instead, the deputy marshal attempted to invoke Section 5 of the 1850 law, by calling out a posse comitatus, gathering citizens to enforce the law. When that failed, he called upon three of the city’s militia companies––two of whom refused to respond. None of the runaways were recaptured, and as a biracial crowd of protesters flooded the street, the slaveholders hurriedly departed the city. [16]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

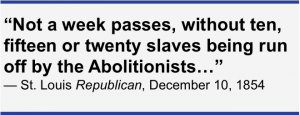

Back in Missouri, the St. Louis Republican fumed over the proceedings which had unfolded in Chicago. The “total failure of a recent attempt to execute the Fugitive Slave Law in Chicago,” was unacceptable in the eyes of the Missouri serial. “In Chicago the law is powerless,” the paper seethed, “and a Southern man, who goes there in pursuit of his property, does so at the peril of his life.” The “nullification” of the law had helped “seventeen slaves, belonging to citizens of this county” escape the clutches of their slaveholders. Moreover, slave stampedes were becoming uncomfortably common in the St. Louis area. “Not a week passes, without ten, fifteen or twenty slaves being run off by the Abolitionists,” the paper declared. Unwilling to acknowledge that enslaved people could harbor their own aspirations for freedom and plot their own escapes, the paper maintained that “these negroes have not left good homes without the aid and persuasion of white men” and “free negroes.” In order to curb these influences, the Republican demanded “a better police force,” which could be put to work expelling from St. Louis “every free negro who cannot establish his right to be here.” [17]

Back in Missouri, the St. Louis Republican fumed over the proceedings which had unfolded in Chicago. The “total failure of a recent attempt to execute the Fugitive Slave Law in Chicago,” was unacceptable in the eyes of the Missouri serial. “In Chicago the law is powerless,” the paper seethed, “and a Southern man, who goes there in pursuit of his property, does so at the peril of his life.” The “nullification” of the law had helped “seventeen slaves, belonging to citizens of this county” escape the clutches of their slaveholders. Moreover, slave stampedes were becoming uncomfortably common in the St. Louis area. “Not a week passes, without ten, fifteen or twenty slaves being run off by the Abolitionists,” the paper declared. Unwilling to acknowledge that enslaved people could harbor their own aspirations for freedom and plot their own escapes, the paper maintained that “these negroes have not left good homes without the aid and persuasion of white men” and “free negroes.” In order to curb these influences, the Republican demanded “a better police force,” which could be put to work expelling from St. Louis “every free negro who cannot establish his right to be here.” [17]

While Missourians denounced Chicago’s open defiance of the law, the 17 freedom seekers moved on to safer territory. Less than a week later, one paper reported that “the slaves had all reached Canada safely.” Moreover, the Chicago Democrat claimed that one of the escapees, the alleged daughter of Pierre Chouteau, was married to a white St. Louis man by a Catholic priest in Chicago. [18] In total, the October and November 1854 stampedes had resulted in the freedom of over 30 enslaved Missourians.

The stampedes had a clear and noticeable effect on the St. Louis slaveholders impacted by them. By 1860, Pierre Chouteau’s slaveholdings had dwindled down to just five people (from 15 a decade earlier). Yet Chouteau only conceded to census takers that one of his bond persons was a “fugitive from the state.” [19] Likewise, his neighbor Emanuel Block held three enslaved people as of 1860, considerably less than the 24 he had claimed in 1850. [20] Richard Berry, who had “lost five out of six” slaves in the November 1854 stampede, held two in 1860, while Martin Wash, the slaveholder of 10 slaves in 1850, held just one enslaved man in 1860. [21]

FURTHER READING

The initial reports on the stampedes were published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat (Newspapers.com) on October 24, November 1 and November 30, 1854. Later, the St. Louis Republican (State Historical Society of Missouri) printed a detailed editorial column on December 10, 1854 denouncing the failure to capture the 17 freedom seekers in Chicago.

The October and November 1854 stampedes from St. Louis have received little attention in scholarship, until Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018). In his chapter on Missouri and Illinois, Blackett mentions both escapes in the context of an “upsurge of stampedes” from St. Louis, which “troubled” slaveholders and exposed the precariousness of slavery in a border state. [22]

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- St. Louis MO Democrat, October 24, 1854 (Newspapers.com)

- St. Louis MO Democrat, November 30, 1854 (Newspapers.com)

- St. Louis MO Republican, December 9, 1854 (SHSM)

- Washington, D.C. Sentinel, December 12, 1854 (GenealogyBank)

- St. Louis merchant Pierre Chouteau held 15 enslaved people in 1850 (Ancestry)

- Richard Berry held three enslaved people in the 1850 Census (Ancestry)

[1] “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854.

[2] “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854.

[3] “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854; “Stampede Among the Africans,” Akron, OH Summit County Beacon, November 8, 1854; “Stampede Among the Africans,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, November 18, 1854; “Another Slave Stampede,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, December 30, 1854.

[4] Lea VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: Life on Slavery’s Frontier, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 189-191; “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854; 1850 US Census, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 121, Ancestry; 1860 US Census, Ward 4, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1020, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 4, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Morrison’s St. Louis Directory, for 1852, (St. Louis: Missouri Republican Office, 1852), 47, [WEB]; Find A Grave, [WEB]; “Over Jordan,” Chicago Weekly Democrat, December 16, 1854.

[5] “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854; 1850 US Census, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 119, Ancestry; 1860 US Census, Ward 4, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1019, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Kennedy’s Saint Louis City Directory for the year 1857, (Saint Louis: R.V. Kennedy, 1857), 24 [WEB] // Emancipations, St. Louis Circuit Court, NPS, [WEB] // Find A Grave, [WEB]

[6] “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854; 1850 US Census, Ward 2, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1276, Ancestry; Morrison’s St. Louis Directory, for 1852, 94, 172 [WEB]; Find A Grave, [WEB]; Green’s Saint Louis Directory for 1845, (Saint Louis, A. Fisher, 1844), 123, [WEB].

[7] “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854; “The Fugitive Slaves,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 1, 1854.

[8] For the story of Charlotta Pyles, see Laurence C. Jones, “The Desire for Freedom,” The Palimpsest 8:5 (May 1927): 153-163, [WEB]; Hallie Q. Brown, Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, reprint, 1926), 38, [WEB]; Berry DeRamus, Forbidden Fruit: Love Stories from the Underground Railroad (New York: Atria Books, 2005), 110-114.

[9] “African Exodus,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, October, 24, 1854; “The Fugitive Slaves,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 1, 1854.

[10] “Negro Riot,” St. Louis Republican, October 20, 1854; VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott, 301-302. Revels autobiography, quoted in U.S. Congressional Bioguide.

[11] “Negro Riot,” St. Louis Republican, October 20, 1854; “The Negro Riot,” St. Louis Republican, October 26, 1854; “Church Rioters,” St. Louis Republican, November 1, 1854; “Recorder’s Court,” and “County Jail,” St. Louis Republican, November 2, 1854; “White vs. Black,” St. Louis Republican, November 9, 1854. Authorities released Revels on November 11 on the grounds that the preacher had already been fined twice for being in the state without a license. “Discharged,” St. Louis Republican, November 14, 1854. Historian Lea VanderVelde noted that multiple African Americans applied for licenses soon after the October 1854 incident. See VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott, 434, n116.

[12] “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854.

[13] “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854; “$1,000 Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 6, 1854. The reward posted in the Missouri Republican pertained to the seven escapees named, and was co-signed by Richard Berry, Martin Wash and Martin W. Wash. It appears that Lunsford Johnson, Emily and the three children were claimed by Berry, while Spencer and David were held by the Wash family. For more on Berry’s slaveholding past, see “What is to Be Done Now!,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854; Thomas Berry Estate Sale, September 13, 1850, Slave Sales Court Ordered, NPS, [WEB]; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, South Half of Central St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Laws of the State of Missouri, passed by the Nineteenth General Assembly, (Jefferson, MO: James Lusk, 1857), 796-797, [WEB]; 1850 U.S. Census, District 82, St. Louis County, MO, Families 1121 and 1246, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Central Township, St. Louis County, MO, Families 473 and 495, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 82, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Central Township, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[14] “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854; “$1,000 Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 6, 1854; “Passengers by the U.G.R.R.,” Chicago Weekly Democrat, December 9, 1854; “News from the Fugitive Slaves,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, December 8, 1854.

[15] “What is to Be Done Now!,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854; “Slave Hunt in Chicago,” Chicago Free West, December 14, 1854; “Great Excitement, Slave Catchers Again Defeated,” Chicago Weekly Democrat, December 16, 1854; Richard Cahan, A Court that Shaped America: Chicago’s Federal District Court from Abe Lincoln to Abbie Hoffman, (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2002), 20, [WEB].

[16] “The Constitution and Law Nullified in Chicago,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 9, 1854; “What is to Be Done Now!,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854; “Slave Excitement at Chicago,” New York Herald, December 9, 1854; “Slave Excitement at Chicago,” Baltimore Sun, December 9, 1854; “Fugitive Slave Excitement in Chicago,” Washington, D.C. Sentinel, December 12, 1854; “Fugitive Slave Case,” Chicago Weekly Democrat, December 16, 1854.

[17] “What is to Be Done Now!,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854.

[18] “Brisk Business on the Underground Railroad,” Worcester, MA Spy, December 13, 1854; “Over Jordan,” Chicago Weekly Democrat, December 16, 1854.

[19] 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 4, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry.

[20] 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 5, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry.

[21] “What is to Be Done Now!,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 82, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Central Township, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry.

[22] Richard J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 145.