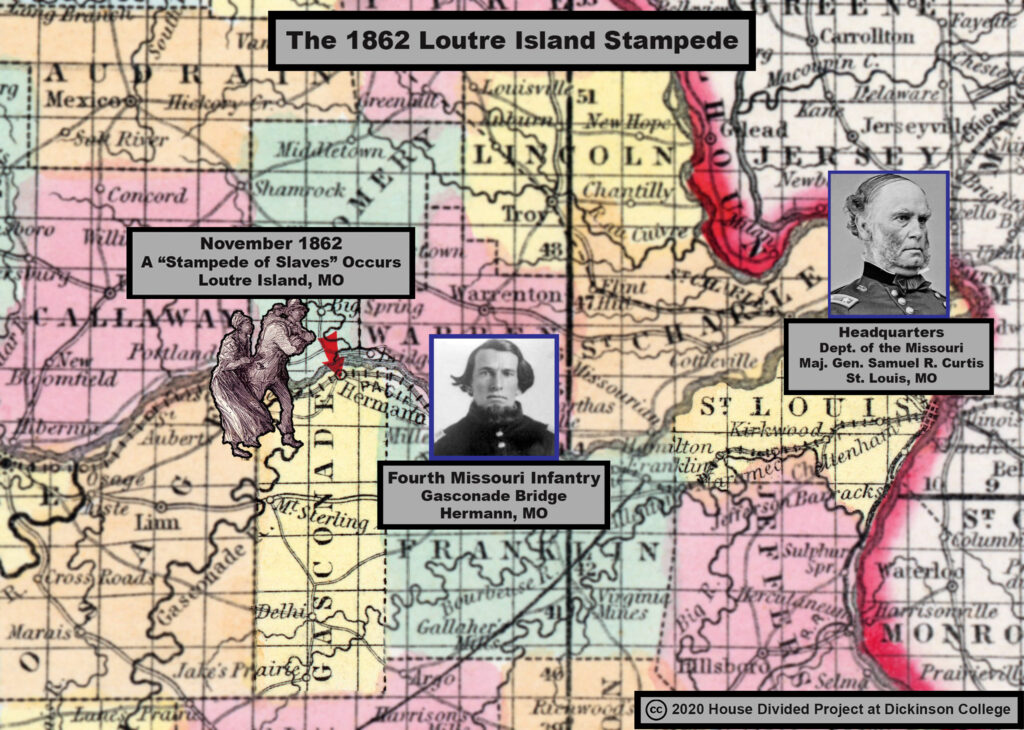

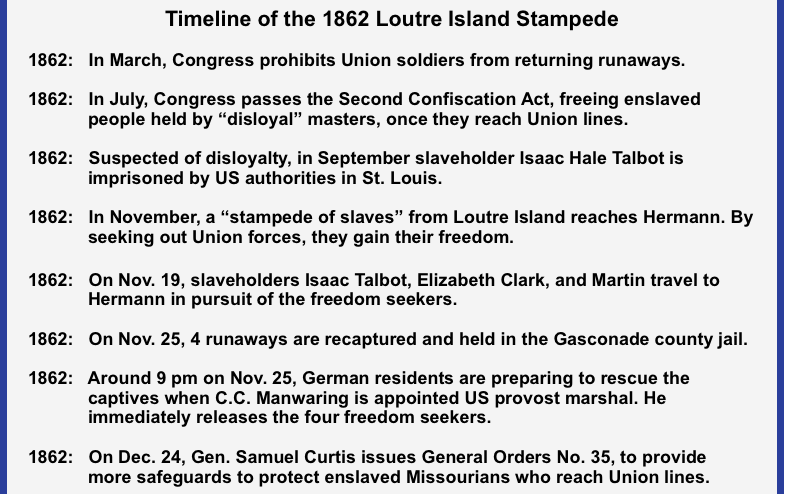

DATELINE: NOVEMBER 1862, GASCONADE BRIDGE, NEAR HERMANN, MO

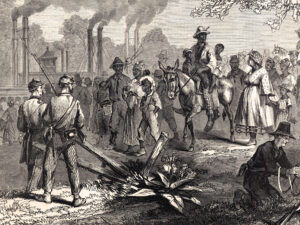

Enslaved people seeking refuge behind Union lines. (House Divided Project)

In November 1862, Union soldiers guarding a vital bridge crossing near Hermann, Missouri opened their lines to allow “a stampede of slaves” from nearby Loutre Island to pass through. Once behind Union lines, the group of enslaved Missourians believed they had finally realized their hard-won freedom. So did the Union soldiers who greeted them, however curtly. The officer on duty, Capt. Bathasar Mundwiller of the Fourth Missouri Infantry, was short on rations and had “no work for them,” so he ordered the freedom seekers out of his camp, assuring them they could find work throughout Union-controlled Gasconade county, where “no one could interfere with them.” [1]

Comforting as Mundwiller’s words may have been, the status of the thousands of enslaved men, women, and children flocking to Union encampments across the country was anything but settled. Despite federal legislation that protected these runaways or “contrabands,” as they were called during wartime, and despite the recent announcement of President Abraham Lincoln’s impending Emancipation Proclamation, many Missouri slaveholders refused to relinquish their claims to lucrative human property without a fight. They still asserted that the Union’s various antislavery policies did not change anything for “loyal” slaveholders from states like Missouri which had rejected secession. On Wednesday, November 19, 1862, three defiant slaveholders thus clattered into Gasconade county and had local authorities arrest four of the freedom seekers from Loutre Island. [2] Yet as they would soon discover, recapturing runaways was no simple task in Gasconade county, home to a sizable community of German emigrants who were not shy about expressing their anti-slavery views. The events that followed reveal how enslaved Missourians’ pursuit of freedom collided with new legal and political developments to help shift the balance of power in wartime Missouri.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

An initial dispatch fired off by a local citizen to Union authorities reported that “a stampede of slaves had taken place from beyond the river.” Subsequently his letter, including its mention of a “stampede,” was reprinted in the St. Louis Missouri Democrat, the New York-based National Anti-Slavery Standard and Douglass’ Monthly. The same letter also served as the basis for a brief report about the same “stampede of slaves” published by the New York Tribune in early December. President Abraham Lincoln may well have perused one of those many press reports. Just weeks later in January 1863, Lincoln privately told two Republican senators that “the negroes were stampeding in Missouri.” Whether or not Lincoln had specifically called to mind the Loutre Island escape, the episode was part of the growing tide of “stampedes” in late 1862 that informed the president’s strategy to push for compensated emancipation in Missouri. [3]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Capt. Bathasar Mundwiller of Company E, Fourth Missouri Infantry, ordered the freedom seekers from Loutre Island to find work in Gasconade county (Geni)

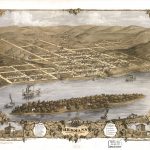

The enslaved people who made their way behind Union lines in November 1862 had escaped from Loutre Island, a narrow strip of fertile bottomland situated directly across the Missouri river from the town of Hermann. Unfortunately, neither local presses nor Union officers bothered to record any details about the freedom seekers, even such basic markers as how many individuals crossed the Gasconade bridge and filed into Captain Mundwiller’s camp.

What is clear is that these unnamed refugees from slavery fled the farms of three slaveholders, widely-reputed to be Confederate sympathizers. Two escapees were claimed by Isaac Hale Talbot, whose family had lived on Loutre Island for decades. On the eve of the war, Talbot held as many as 26 people in chains, and his loyalties became suspect during the summer of 1862, when he attempted to avoid compulsory service in Missouri’s enrolled militia by fleeing to Canada or Europe. Union authorities caught up with him, however, detaining Talbot in a St. Louis prison cell for the better part of a month. The other slaveholders were Elizabeth Clark, a suspected secessionist who had laid claim to nine enslaved people in 1860, and a man identified only as Martin. [4]

Gasconade county, Missouri. (House Divided Project)

By the fall of 1862, most enslaved people throughout war-ravaged Missouri, and indeed much of the south, had come to recognize that the surest path to freedom, unpredictable as it was, lay behind Union lines. The enslaved men and women living at Loutre Island would have been well aware of the Union outpost located just miles south at Hermann. They might also have had an inkling about the reception that awaited them. After all, the ranks of the Fourth Missouri Infantry, which was posted at Gasconade bridge, were filled with German immigrants, a burgeoning population within the state ever since the late 1840s. Many Germans had fled their homeland following the failed liberal revolution of 1848. For this reason, many of the new German immigrants tended to hold more anti-slavery views than most native-born southern whites. Moreover, Gasconade county itself was home to a large number of European-born residents, also more likely to be sympathetic to the freedom seekers. Writing to a St. Louis-based German-language newspaper shortly after the escape, one local resident declared that “Hermann’s free Germans” did not want their county turned into “a slave hunting area.” [5]

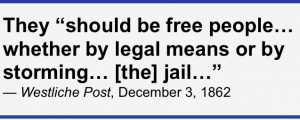

On November 19, not long after Captain Mundwiller permitted the freedom seekers to pass through his lines and ordered them to find work, slaveholders Isaac Talbot, Elizabeth Clark, and Martin travelled to Hermann and sought out the town’s justice of the peace, a Dutch immigrant named John B. Miché. He refused to arrest the freedom seekers under state laws, as the slaveholders insisted he do. Backed by several of the town’s prominent German residents, Miché reasoned that because the state had been under martial law since August 1861, “the matter belonged before the Federal authorities.” Back in St. Louis, the German Westliche Post thundered its approval of Miché’s actions, praising his adherence “to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican.” Undeterred, around a week later the slaveholders cajoled another justice of the peace, a German-born man named Karl Sandberger, to issue the warrants and arrest four freedom seekers, who on Tuesday, November 25 found themselves behind bars at the Gasconade county jail. The news “passed through town and surroundings like wildfire,” wrote one observer, and Hermann’s German population quickly mobilized in protest. By that afternoon, a large crowd had congregated outside the jail, uttering “threats and curses” at the slaveholders and vowing that the captives “should be freepeople” in the morning, “whether by legal means or by storming… [the] jail.” [6]

On November 19, not long after Captain Mundwiller permitted the freedom seekers to pass through his lines and ordered them to find work, slaveholders Isaac Talbot, Elizabeth Clark, and Martin travelled to Hermann and sought out the town’s justice of the peace, a Dutch immigrant named John B. Miché. He refused to arrest the freedom seekers under state laws, as the slaveholders insisted he do. Backed by several of the town’s prominent German residents, Miché reasoned that because the state had been under martial law since August 1861, “the matter belonged before the Federal authorities.” Back in St. Louis, the German Westliche Post thundered its approval of Miché’s actions, praising his adherence “to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican.” Undeterred, around a week later the slaveholders cajoled another justice of the peace, a German-born man named Karl Sandberger, to issue the warrants and arrest four freedom seekers, who on Tuesday, November 25 found themselves behind bars at the Gasconade county jail. The news “passed through town and surroundings like wildfire,” wrote one observer, and Hermann’s German population quickly mobilized in protest. By that afternoon, a large crowd had congregated outside the jail, uttering “threats and curses” at the slaveholders and vowing that the captives “should be freepeople” in the morning, “whether by legal means or by storming… [the] jail.” [6]

To view an interactive map of this stampede, check out our StorymapJS version at Knight Lab

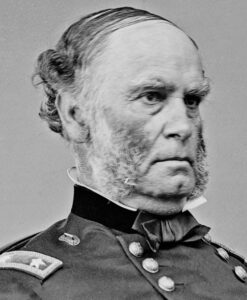

Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, commander of the Department of the Missouri. (House Divided Project)

In the meantime, a concerned German editor and activist named F.A. Nitchy had written to Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis, then commander of the Union’s Department of the Missouri, which was headquartered in St. Louis at the northwest corner of Fourth Street and Washington Avenue. “A stampede of slaves” had occurred, Nitchy explained, and slaveholders were determined to seize the freedom seekers under Missouri’s state slave code. The situation “may give rise to a conflict between State laws and Federal authority,” Nitchy argued. The Second Confiscation Act liberating enslaved people held by disloyal masters was a federal law, and Unionists like Nitchy believed that local officials could not vet slaveholders’ loyalty; only federal officials or the US military could do so.

The afternoon mail brought a dispatch from Curtis, who affirmed that Miché “did right in withholding his warrant,” and advised him to “arrest and bring before [a] Provost Marshal these slaveholders, if they occasion any more trouble.” Provost marshals, the US army’s system of military police, had become responsible for protecting freedom seekers who were likely free under the Confiscation Acts. But there was no provost marshal in Gasconade County. Nitchy and local Unionists pleaded with Curtis to appoint a local Gasconade county man, C.C. Manwaring, as acting provost marshal for the region. Their choice made sense. Manwaring after all was a leading local voice advocating for emancipation in Missouri. Days earlier, he had been elected to represent Gasconade county in the Missouri State House, where in 1863 he would serve on a committee that recommended a statewide convention to consider eliminating slavery. [7]

As they awaited further word from Curtis, Hermann’s angry citizenry had settled on a plan to “abstain from any violence until nine o’clock at night,” when they apparently meant to storm the jail and rescue the captive freedom seekers. With the hour rapidly approaching and no word yet from department headquarters, tensions rose to a fever pitch, and local residents began to arm themselves with “weapons and crushing tools.” Just around 9 pm, Manwaring’s appointment arrived via telegraph, and the new acting provost marshal immediately released the four freedom seekers. [8]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

By running to Union lines, the enslaved Missourians had not only forced the issue of their own freedom, but also prodded Union officials to take additional action to ensure that recent legislation from Washington was being effectively implemented. After all, their escape came on the heels of three critical new developments in federal policy. First in March 1862, Congress passed the revised Articles of War, prohibiting Union soldiers from returning runaways to their slaveholders. Then in July, Congress approved the Second Confiscation Act, authorizing Union forces to liberate enslaved people of any “disloyal” persons as “captives of war,” declaring them “forever free.” Finally in September, President Lincoln publicly unveiled his Emancipation Proclamation, set to take effect on January 1, 1863, promising to liberate all slaves in areas of rebellion and not under Union control. Acting Provost Manwaring had to consider all of these new developments as he sat down in late November and laid out his justifications for “turning them loose.” First, he argued, the group had come within the lines of the Fourth Missouri and “placed themselves under the protection of Capt. Mundweller.” Manwaring reasoned that because the revised Articles of War made it clear that Union soldiers were to have no part in returning runaways, once the freedom seekers had entered Mundwiller’s lines they could not be forcibly re-enslaved. Manwaring then proceeded to describe the slaveholders, taking pains to demonstrate that each were known to be Confederate sympathizers. This was crucial, as the Second Confiscation Act allowed the armies to liberate runaways from disloyal persons, even if they were resident in a loyal state –like Missouri. [9]

Although Manwaring’s legal justifications held up, concerns lingered about how to safeguard the many other freedom seekers who claimed freedom under the Second Confiscation Act. Having learned a lesson from the events at Hermann, F.A. Nitchy and other Republicans urged US military higher-ups to make it clear that the authority to determine who was a loyal or disloyal slaveholder under the law rested with the US army, and it alone. They hoped to prevent slaveholders from scouring the countryside until they found a local official willing to aid them, and instead force slaveholders to deal directly with the US army. “It is to be expected, that many similar cases will arise,” Nitchy advised Curtis. Hermann Unionists pleaded with the general to issue “an authoritative order or re-publication of orders already existing touching the subject.” [10]

One month later on December 24, Curtis issued General Orders No. 35, which provided that all provost marshals within the Department of the Missouri must “protect the freedom and persons of all such captives or emancipated slaves, against all persons interfering with or molesting them.” Should any slaveholders like Talbot, Clark, and Martin dare to come behind US lines and try to re-enslave freedom seekers, the order stipulated, provost marshals were to arrest them on the spot. The orders also instructed provost marshals to issue “certificates of freedom” to all enslaved people who were likely free under the Second Confiscation Act. Soon after, enslaved people throughout Missouri who blazed paths to Union lines were obtaining military-issued certificates. In February 1863, two enslaved men, Henry and Henderson Bryant, escaped from Boone county and made their way behind Union lines at Jefferson City, where they secured certificates of freedom. [11] Through their actions, the enslaved individuals who launched the Loutre Island stampede prompted Union officials in Missouri to expand the protections offered freedom seekers under the Second Confiscation Act, helping to pave the way for slavery’s destruction in the state.

Over the winter of 1862-1863, loyal slaveholders complained to President Lincoln that General Orders No. 35 was enticing their enslaved people away. Lincoln was attentive to what loyal slaveholders had to say, because he hoped to pass compensated emancipation in Missouri; the November 1862 elections had resulted in a pro-emancipationist majority in the state legislature (which included state legislator-elect Manwaring from Hermann). On January 9, Missouri senator John Henderson asked Lincoln to instruct “Genl Curtis to so manage the negro question in Missouri, as to avoid ill feeling on the part of Union men, for a week or few days. In that time I hope to have a bill passed to settle it forever.” Henderson feared that Curtis’s General Orders No. 35 were antagonizing loyal slaveholders and jeopardizing the coalition needed to pass compensated emancipation. Later that same day, Lincoln called two Republican senators, Illinois’s Orville Browning and New Hampshire’s John Hale, into the White House. “Since the [Emancipation] proclamation the negroes were stampeding in Missouri,” Lincoln told the two senators, “which was producing great dissatisfaction among our friends there.” Lincoln urged the two men to support a $25 million congressional appropriation for compensated emancipation in Missouri. Meanwhile, through Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and general-in-chief Henry Halleck, Lincoln directed Curtis to rescind his General Orders No. 35. Curtis eventually persuaded Lincoln to let the orders stand, but it remained clear that freedom seekers’ enthusiastic response to General Orders No. 35 was complicating the president’s hopes for accomplishing abolition by state action, rather than through military emancipation. [12]

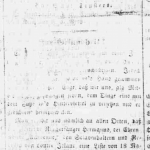

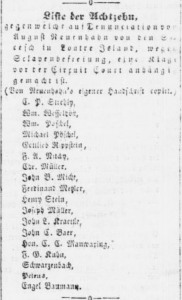

Names of the eighteen alleged abolitionists. (Hermanner Volksblatt, April 11, 1863, Library of Congress)

Even with General Orders No. 35 still on the books, the Loutre Island slaveholders were determined to recover damages from the Hermann residents who played an active role in aiding the freedom seekers. In April 1863, a local newspaper published the names of 18 alleged abolitionists: C.P. Strehly, William Wesselhoeft, William Poeschel, Michael Posechel, Gottlieb Rippstein, F.A. Nitchy, Chr. Mueller, John B. Micke, Ferdinand Metzler, Henry Stein, Joseph Mueller, John L. Kraettle, Jon C. Baer, F.G. Kuhn, Schawrzenbach, Petrus, Engel Baumann, and C.C. Manwaring. Slaveholders Talbot, Clark, and Martin reportedly planned to file charges in state court for $2,000 worth of damages, some of which was expected to go to a local man named Achtenne, who had acted as a slave catcher and aided the slaveholders back in November. But the same Hermann paper that reported the pending charges expressed confidence that the enslavers had no case. U.S. authorities have “conclusive proof that those rebels of Loutre Island” were disloyal and therefore had “forfeited all their property” under the Second Confiscation Act. It is unclear if charges were ever filed. [13]

While slaveholders mulled legal action through state and local courts, the status of the Loutre Island freedom seekers remained unclear—even to some US military officials. When some of the freedom seekers returned to Hermann several months later in May 1863, a slave catcher working for John Plunkett (Mrs. Clark’s overseer) tried to convince the new provost marshal, NJ Camp, to return them to Clark. Camp wrote to departmental headquarters for guidance, noting that “the late article of war forbids me returning fugitives,” and asking for “written instructions how to act.” Two days later, Camp received a short response from department headquarters, directing him to follow General Orders No. 35. The US army would not return freedom seekers to Mrs. Clark; instead they would protect them. [14]

FURTHER READING

The most detailed accounts of the Loutre Island stampede are found in the correspondence between Nitchy, Manwaring and General Curtis. These documents are reprinted in the edited compilation Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation. The St. Louis Missouri Democrat reprinted excerpts of Nitchy’s correspondence, with additional commentary, while the German-language Westliche Post, also of St. Louis, ran an eyewitness account penned by a German resident of Hermann. [15]

Despite contemporary news coverage, the episode has been largely overlooked by historians. However, scholars have written about Curtis’s General Orders. No. 35 and the controversy those new guidelines stirred back in Washington. Leslie Schwalm situates the orders within the broader context of Curtis’s appointment as department commander in September 1862. Once in charge, she notes, Curtis began a vigorous push “to ensure the widest possible application” of the Confiscation Acts. General Orders No. 35 marked the culmination of Curtis’s efforts, though President Lincoln, fearful Curtis might be going too far and antagonizing slaveholding Missouri Unionists, urged the department commander to “keep peace” and mollify his orders. [16] Joseph Reidy traces Curtis’s campaign to broadly implement the Confiscation Acts back even further. Starting in February 1862, while commanding Union troops near Helena, Arkansas, Curtis had been issuing certificates of freedom to runaways, though as Reidy observes, with mixed results. In a theatre of war where Union units moved frequently and in unpredictable ways, those certificates could either be worthless, or even backfire should Confederate troops overtake certificate-bearing freedom seekers. [17] Scholars have also stressed the uncertainty clouding the fate of freedom seekers who found their way behind Union lines during the early stages of the war. While recounting a similar confrontation between slaveholders and U.S. authorities in nearby Pacific, Missouri during the spring of 1862, Chandra Manning emphasizes the “vagueness” of federal policy and U.S. officers’ struggles to interpret and enact it on the ground. [18]

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- Enslaved people behind Union lines, near Yorktown, Virginia, May 1862. (Library of Congress) Photo taken by John F. Gibson

- Young enslaved men behind Union lines near Washington, D.C., c. 1861. (Library of Congress) Photographer unknown.

- Union encampment at Cumberland Landing, Virginia, 1862. (Library of Congress)

- Suspected of disloyalty for attempting to flee the state, slaveholder Isaac Hale Talbot pleads his case with U.S. authorities in St. Louis. Weeks later, he would again clash with Union officers in Hermann while attempting to re-enslave several freedom seekers. (Ancestry)

- Hermann, Missouri in 1869. (Library of Congress)

- A c.1930s view of a bridge across the Missouri River at Hermann. A smaller Civil War-era bridge was destroyed by Confederates in October 1864. (Library of Congress)

- Report announcing that slaveholders intend to sue Hermann residents who aided the freedom seekers. (Hermanner Volksblatt, April 11, 1863, Library of Congress)

[1] C.C. Manwaring to Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, November 26, 1862, in Ira Berlin, Barbara J. Fields, Thavolia Glymph, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland (eds.), Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985-2013) series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 439-440.

[2] “Slave Catching at Hermann,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 29, 1862.

[3] F.A. Nitchy to Curtis, November 19, 1862, in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 438-439; “Slave Catching at Hermann,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 29, 1862; “Reported Capture of a Supply Train,” New York Tribune, December 5, 1862; “Slave-Catching Under Difficulties,” New York National Anti-Slavery Standard, December 13, 1862; “Slave-Catching Under Difficulties,” Douglass’ Monthly, January 1863, 775. On Lincoln’s comments, see this post.

[4] Isaac H. Talbot to Provost Marshal of St. Louis, September 25, 1862, and Talbot to Col. W.L. Lovelace, September 25, 1862, Union Provost Marshals’ File of Papers Relating to Individual Civilians, 1861-1867, RG 109, National Archives, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Loutre Township, Montgomery County, MO, Ancestry; Manwaring to Curtis, November 26, 1862, in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 439-440.

[5] “Die Freibeit triumpbirt!” St. Louis, MO Westliche Post, December 3, 1862 (translated using GoogleTranslate); Regina Donjon, German & Irish Immigrants in the Midwestern United States,1850-1900 (London: Palsgrave MacMillan, 2018), 187-188; Bathasar Mundwiller, Find-A-Grave, [WEB]; On German immigrants and slavery, see Kristen Layne Anderson, Abolitionizing Missouri: German Immigrants and Racial Ideology in Nineteenth Century America (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2016).

[6] “Slave Catching at Hermann,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 29, 1862; “Die Freibeit triumpbirt!” St. Louis, MO Westliche Post, December 3, 1862 (translated using GoogleTranslate); 1870 U.S. Census, Hermann, Gasconade County, MO, Ancestry

[7] “Slave Catching at Hermann,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 29, 1862; Nitchy to Curtis, November 19, 1862, in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 438-439; “Missouri Legislature,” St. Louis MO Republican, December 1, 1862; Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Missouri at the First Session of the Twenty-Second General Assembly (Jefferson City, MO: n.p., 1863) 243-256, [WEB]. For the location of Curtis’s headquarters (the present-day site of the Missouri Athletic Club), see Official Register of Missouri Troops for 1862 (St. Louis: Adjutant General’s Office, 1863), 115 [WEB]. In May 1864, Manwaring was murdered by Confederate guerrillas. See “A Guerrilla Raid,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, reprinted in Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1864.

[8] “Slave Catching at Hermann,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 29, 1862; “Die Freibeit triumpbirt!” St. Louis, MO Westliche Post, December 3, 1862 (translated using GoogleTranslate).

[9] Manwaring to Curtis, November 26, 1862, in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 439-440; James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), 210, 226-236.

[10] Nitchy to Curtis, November 19, 1862, in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 439-443.

[11] General Orders No. 35, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), series 1, vol. 22, pt. 1, 868-871, [WEB]; On Henry and Henderson Bryant, see OR, ser. 1, vol. 34, pt. 4, 191, [WEB].

[12] John Henderson to Lincoln, [January 9, 1863], Abraham Lincoln Papers, LOC, [WEB]; Theodore Calvin Pease and James G. Randall (eds.), The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning (Springfield, IL: Illinois State Historical Society, 1925), 1:611-612, [WEB]; Stanton to Curtis, January 14, 1863, and Halleck to Curtis, January 15, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, pt. 2, 41, [WEB].

[13] Hermann Hermanner Volksblat, April 11, 1863. Original available at Chronicling America, Library of Congress. For translation, see Selected Articles of the Hermanner Volksblatt, 1860-1864, St. Louis Civil War Project, Missouri Digital Heritage, [WEB].

[14] N.J. Camp to Capt. C.C. Allen, May 20, 1863, Hermann, Mo., RG 109, National Archives (copy at Missouri State Archives, reel F1238. For Allen’s response, see RG 393, pt. 4, entry 1762, vol. 617DMo, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

[15] Nitchy to Curtis, November 19, 1862, Manwaring to Curtis, November 26, 1862, and General Orders No. 35, issued December 24,1862, in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, series 1, vol. 1, book 1, 439-443; “Slave Catching at Hermann,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 29, 1862; “Die Freibeit triumpbirt!” St. Louis, MO Westliche Post, December 3, 1862 (translated using GoogleTranslate).

[16] Leslie A. Schwalm, Emancipation’s Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 55.

[17] Joseph P. Reidy, Illusions of Emancipation: The Pursuit of Freedom and Equality in the Twilight of Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 84.

[18] Chandra Manning, Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 196-197.