In July of 1841, Illinois abolitionist Alanson Work and two of his students, George Thompson and James Burr “attempted to induce slaves of four different masters in Marion County to leave their owners and travel through Quincy and Chicago to freedom.”

These four enslaved people, presumably wary of the white abolitionists, instead alerted their slaveholders of the abolitionists’ presence. Work, Thompson, and Burr were then arrested and sentenced to twelve years in prison—the second longest slave stealing sentence in Missouri history. [1]. These three men were not the only abolitionists sent to prison in Missouri for “slave stealing,” the term denoted to describe those who are caught assisting the enslaved in their escape attempts. In Missouri courts, slave stealing was an act of grand larceny, and at least 42 “slave stealers” were imprisoned by Missouri circuit courts between 1837 and 1862.[2]

Legal scholar Harriet Frazier places this “slave stealing” episode within the larger historical context of centuries of escapes and the growth of the Underground Railroad in the decades leading up to the Civil War in her book Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those Who Helped Them (2004). Frazier’s book presents “unique and valuable information” about enslaved and free Blacks living in Missouri in the 18th and 19th centuries as well as the agents and processes of the Underground Railroad. Frazier’s background as a law professor at Central Missouri State University and a licensed attorney provides a unique lens to thoroughly analyze the ways that law, culture, and society shaped the nature of slavery and escapes in Missouri from 1763 to 1865.[3] The author presents a comprehensive overview of the history, legal system, and people in Missouri that shaped the experiences of the enslaved, as well as actions taken by slaves to assert their agency and achieve freedom. Frazier’s book notes numerous individuals and stories from the historical record that shed insight on the nature of slave stampedes.

Frazier claims that slave stampedes and the public panic surrounding them did not become significant in Missouri until the 1850s, following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act.[4] The term “stampede” is used once, in a reference to the Louisiana Journal article entitled “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County,” which describes the June 1860 escape of 11 enslaved people belonging to seven different slaveholders from Lewis County. Frazier does not comment on the use of the term “stampede,” but she writes that “these accounts of absconding slaves all appeared in Missouri newspapers after the Thirty-First Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in September 1850,” suggesting a direct connection between the Fugitive Slave Act and the recognition of slave stampedes in the media.[5]

Frazier also provides the names and stories of numerous abolitionists living in Missouri in the years leading up to the Civil War. In the fourth chapter, which describes the lives of numerous notable free blacks in the state, the Reverend John Meachum is mentioned again (learn more here). According to Frazier, Meachum’s abolition work primarily consisted of purchasing slaves to train them in professional skills such as carpentry and then free them. He also allegedly taught enslaved and free people of color to read and write in the basement of his church, and then, when the operation was shut down by the police, on a steamboat on the Mississippi River. However, a more complicated portrait of Meachum is revealed in a freedom suit filed against him by an enslaved woman named Judy. The decision was made to grant Judy her freedom, but Meachum’s opposition to Judy’s case throughout the trial paints a “less attractive side of Meachum than the one usually presented.”[6] Later in the book, Frazier mentions the 1855 arrest of Mary Meachum, John Meachum’s wife, for attempting to help nine slaves across the Mississippi River in their bid for freedom. In 2001, the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing and Rest Area in St. Louis was dedicated to commemorate this event.[7]

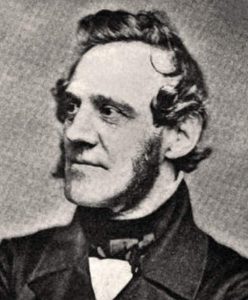

Another notable case was that of Dr. John Doy, who was already known for his friendship with John Brown, an infamous abolitionists who in 1858 freed 11 enslaved Missourians in a spontaneous raid.[8] In January of 1859, Dr. Doy and two other men were caught in Kansas by Missouri slaveholders the company of thirteen freedom seekers. Dr. Doy and one of the men with him, his son, were arrested for slave stealing and taken to Platte County, Missouri.

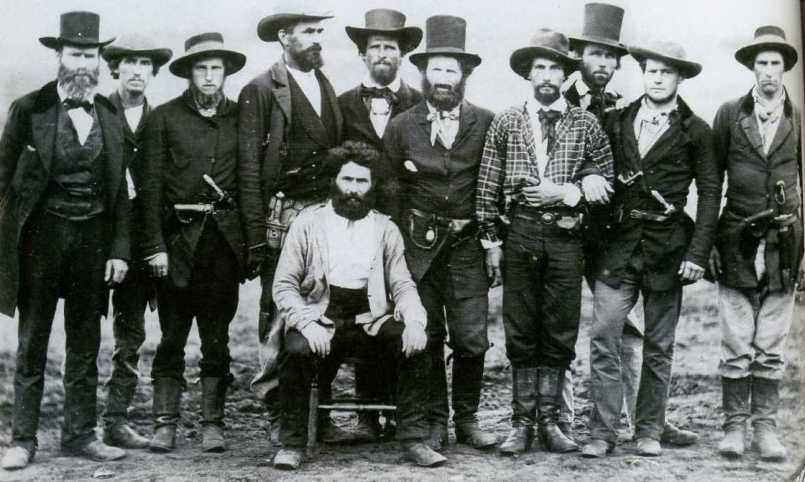

His case became so well known through newspapers and word of mouth that Doy and his son were kidnapped by an angry mob of Missouri slaveholders and almost lynched while awaiting trial. After numerous retrials, Doy was sentenced to five years in prison. However, on July 23, 1859, ten of his friends broke into the Buchanan County jail at midnight and successfully rescued Doy and returned him to Kansas. Dr. Doy wrote about this entire experience in his memoir, The Thrilling Narrative of Dr. John Doy of Kansas (1860), and continued to claim for the rest of his life that he had nothing to do with the escape of the thirteen slaves.[9] Most historians, such as Diane Mutti-Burke, dismiss this claim of Doy’s. Whether he did assist the freedom-seekers or not, however, Doy’s experience, and the experiences of other jailed abolitionists, reveal how much anger the pro-slavery population of Missouri felt towards white abolitionists who “stole” their property and stampeded them to freedom.

[1] Harriet C. Frazier, Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those Who Helped Them, 1763-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2004), 131-134.

[2] Frazier, 124, 131.

[3] “Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those Who Helped Them,” Judy Sweets, Kansas History 28:1 (2005), 75.

[4] Frazier, 101.

[5] Frazier, 102.

[6] Frazier, 76-78.

[7] Frazier, 173.

[8] Frazier, 145-150.

[9] Frazier, 154-161.