DATELINE: NEAR FALL CREEK, ILLINOIS, MARCH 23, 1863

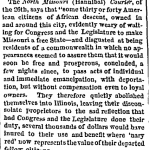

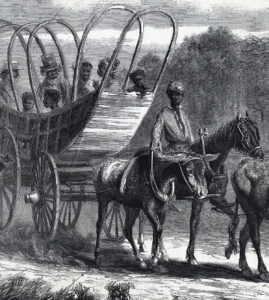

Freedom seekers set out for Union lines. (House Divided Project)

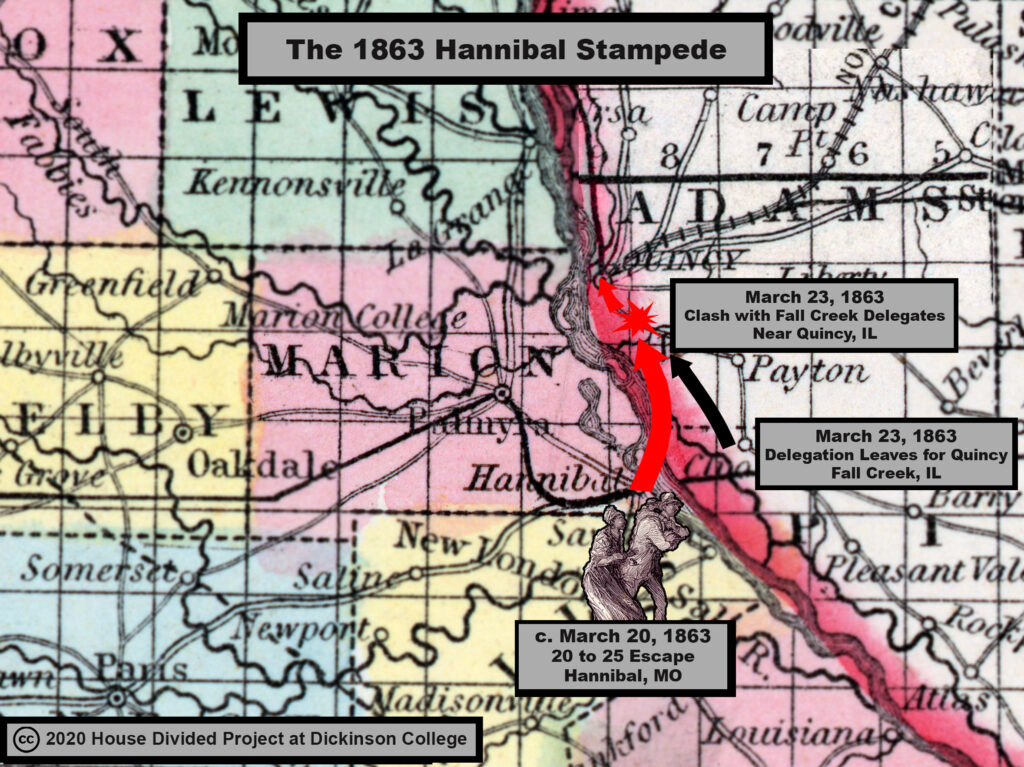

On Monday, March 23, 1863, Wash Minter and around 20 to 25 other freedom seekers who fled slavery in a “stampede” from Hannibal, Missouri, were plodding their way towards Quincy, Illinois. Having successfully crossed the Mississippi River and already traversed several miles through southern Illinois, on the rain-soaked, “almost impassable” road to Quincy, the large group of runaways ran head first into a delegation of fiercely anti-black Democrats from the neighboring town of Fall Creek, Illinois. As it happened, this contingent of white “farmers and workingmen” were bound for a countywide Democratic meeting in Quincy, where later that evening they would pronounce themselves in favor of preserving the Union, but emphatically “opposed to a war for the freedom of the negro.” [1]

Crossing paths with a group of enslaved people capitalizing on the chaos of war to seize their own freedom, these northern Democrats reacted violently. One of the runaways, Wash Minter, later recounted how the “gang of ruffians,” as he called the Democrats, disarmed and robbed the exhausted freedom seekers, many of whom were women and children. [2] Coming just months after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, this tense encounter between freedom seekers and anti-black Democrats along the muddy road to Quincy laid bare how enslaved people’s own determined footsteps towards freedom were upending slavery, much to the discomfort of some white northerners.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

Multiple newspapers throughout the country used the term “slave stampede” to describe the mass escape of enslaved people from Hannibal in late March 1863. Quoting from a report in the Hannibal North Missouri Courier, the Chicago Tribune ran the headline “Slave Stampede,” while the Vincennes (IN) Gazette used the title “Slave Stampede from Hannibal.” The same report was reprinted by newspapers in places such as Saint Joseph, Missouri, Lancaster, Pennsylvania and Atchison, Kansas in April 1863. [3]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Wash Minter and the 20 to 25 other enslaved people who took flight from Hannibal in March 1863 were claimed by four prominent slaveholders from the riverside town in northeastern Missouri. Minter, and possibly his enslaved family members, were held by a 40-year-old well-to-do widow named Sarah Carter. Although his age is unclear, Minter was familiar to many readers in Quincy, having worked for years as a porter at the popular Planter’s House in Hannibal. He was likely hired out (or rented) to work at the hotel, and apparently used the opportunity to earn some of his own wages. Quincy’s Democratic organ, the Herald, later sniped that Minter “can hardly be considered a contraband” (the term commonly applied to enslaved people who crossed into Union lines) “as he has had the use and profit of his own labor for some time past.” [4]

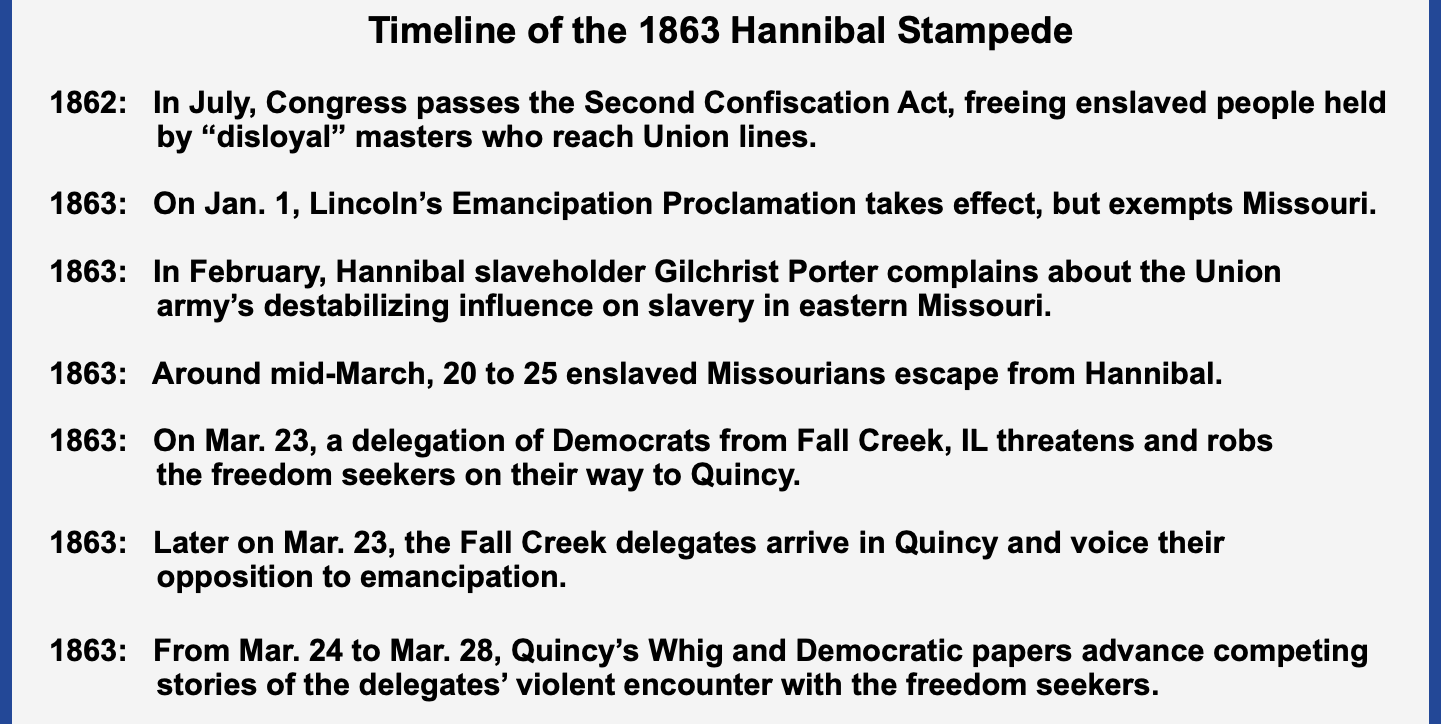

Hannibal, Missouri, c. 1857. (House Divided Project)

The names of Minter’s fellow escapees are unknown, though five fled from another prominent Hannibal slaveholder, 46-year-old Gilchrist Porter. They included 21-year-old Squire, 15-year-old Winston, as well as Squire’s older sister, 27-year-old Bett, who brought her two young children: four-year-old Fred and two-year-old Mary Ellen. Their enslaver, Porter, was a native Virginian and former congressman from Missouri, Porter was then serving as a judge for the state circuit court. [5] Two more bond people escaped from miller Brison Stillwell, also aged 46, who was then serving as mayor of Hannibal. [6] Rounding out the group of freedom seekers were some 15 enslaved people who left the home of Robert F. Lakenan, a 43-year-old attorney. [7]

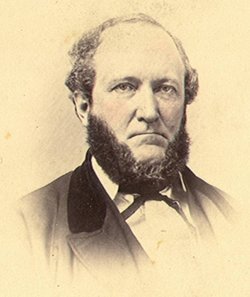

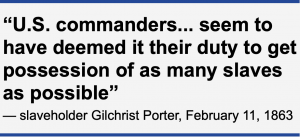

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, white Missourians found themselves deeply divided about the future of their state. While many, such as Robert Lakenan, declared their support for the Confederacy, other slaveholding residents emerged as staunch Unionists. [8] Hannibal’s Judge Gilchrist Porter was among the latter, though along with many other Missouri Unionists, he looked to the U.S. government as the surest source of protection for his enslaved property. In February 1863, on the heels of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Porter fired off a letter to his congressman, but intended for Lincoln’s eyes, in which he complained loudly about “the injury to loyal [slave] owners” brought about by the Union army’s presence and U.S. policies. [9]

Disconcerting as the chaos of war proved for anxious slaveholders like Judge Porter, that very uncertainty offered enslaved Missourians like Wash Minter and his family a glimmer of hope, albeit a very murky one. Enslaved men and women attentively monitored the rapidly changing circumstances war had wrought, eavesdropping on the conversations of their nervous enslavers, and gleaning information via the proverbial grapevine, as free African Americans and other bond people swapped news and stories. In war-torn Missouri, border state slavery, which had long seemed precarious, increasingly unravelled before disgruntled slaveholders’ eyes, as enslaved men and women looked to the Union army as a source of potential liberation. [10]

The path to freedom became somewhat clearer in July 1862, when Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act. The new law freed any enslaved people held by disloyal slaveholders (even if that disloyal enslaver resided in a Union state, such as Missouri). In practice, it meant that if enslaved people could reach Union lines and persuade northern soldiers that their slaveholders were traitorous Confederates, they could gain their freedom. As historian Diane Mutti Burke observes, most northern soldiers within the Department of the Missouri took enslaved people’s word at face value, and were loath to return escapees, even to slaveholders who professed themselves loyal Unionists. Northern soldiers’ willingness to turn a blind eye to legal niceties reflected both the rank and file’s growing disdain for the institution of slavery, as well as pressing practical needs. Two years into a grueling civil war, freed people––both men and women––were proving themselves vital to the functioning of U.S. armies, finding work as laborers, teamsters, cooks, laundresses and nurses. [11]

Hannibal slaveholder and Unionist Gilchrist Porter complained to Lincoln about the effects the Emancipation Proclamation was having on the ground in Missouri. (Find A Grave)

Writing in February 1863, slaveholder Gilchrist Porter seethed that “U.S. commanders… seem to have deemed it their duty to get possession of as many slaves as possible––& to take special pains to inform them that their being employed in Government service, even so short a time, entitles them to their freedom.” Yet even when northern soldiers scrupulously followed the letter of the law, only freeing people held by disloyal slaveholders, the presence of Union forces still had a destabilizing effect on slavery throughout Missouri. Many enslaved men and women held by loyal slaveholders “are strongly tempted to escape… beyond the limits of the State,” Porter warily observed, “as many of them hereabouts have done.” As he scribbled off his note to Lincoln, Porter reflected anxiously on his own holdings in mobile human property. “Before the rebellion broke out I owned & still own 11 slaves,” he added. Scarcely a month later, five of those enslaved people would strike out for their freedom, realizing Porter’s worst fears. [12]

Given the circumstances, the “slave stampede” that followed in late March 1863 came as little surprise to Porter and the rest of Hannibal’s slaveholding elite. The 20 to 25 enslaved men, women and children who crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois perhaps sought freedom and employment behind Union lines, or as Porter outlined, simply decided to capitalize on the upheaval brought about by the war to effect their escape. Minter, for one, undoubtedly had the promises of the Second Confiscation Act in mind. He made a point of telling the editor of the Quincy Whig that he and his fellow escapees fled from disloyal slaveholders who “had deserted them for situations in [Sterling] Price’s [Confederate] army.” [13]

Given the circumstances, the “slave stampede” that followed in late March 1863 came as little surprise to Porter and the rest of Hannibal’s slaveholding elite. The 20 to 25 enslaved men, women and children who crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois perhaps sought freedom and employment behind Union lines, or as Porter outlined, simply decided to capitalize on the upheaval brought about by the war to effect their escape. Minter, for one, undoubtedly had the promises of the Second Confiscation Act in mind. He made a point of telling the editor of the Quincy Whig that he and his fellow escapees fled from disloyal slaveholders who “had deserted them for situations in [Sterling] Price’s [Confederate] army.” [13]

Once on the Illinois side of the river and en route to Quincy, on Monday, March 23, the group encountered the violent gang of Democrats. Although the freedom seekers were “armed to the teeth with revolvers, &c.,” the group numbered many women and children, and even some of the men, like Wash Minter, were balancing their weapons in one arm and their infant children in the other. The mud-spattered, weary group made an easy target for racially-motivated violence, and as Minter later narrated to the Quincy Whig, the band of 15 armed Democrats seized their weapons and snatched around $40 from the freedom seekers, except for Minter. When one of the Illinoisans pointed a pistol at his head and demanded he turn over his weapons, Minter “told them they were welcome to his weapons,” which he “only carried… to defend his property.” Yet when the white men came for his cash, Minter defiantly replied “that they couldn’t have that without killing him first.” Though the Fall Creek delegates reportedly pried upwards of $40 from the other escapees, Minter retained his money, holding steadfast to his newly-realized freedom. [14]

Quincy’s Democratic paper, the Herald, ran the initial story of the scuffle, putting a positive spin on the Fall Creek Democrats’ disarming of the “n––r revolution.” The editors eagerly portrayed the group of heavily armed African Americans traversing the southern Illinois countryside as symptomatic of the perils that “abolition-‘republican’ party” policies posed to white racial hierarchy. When the Quincy Whig responded with an interview of Wash Minter and the freedom seekers’ side of the story, the Herald thundered back, dismissing Minter’s claims that the escapees fled from disloyal slaveholders. With the exception of Lakenan, the Democratic press noted, Carter, Porter and Stillwell were all loyal Unionists, undercutting the escapees’ claims to obtain their freedom behind Union lines. [15]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

The ultimate fate of Wash Minter and his 20 to 25 compatriots is unknown, though it appears their determined “stampede” from Hannibal successfully secured their freedom. No reports of their recapture circulated, and it is unlikely that Union soldiers would have returned the group of runaways, even in light of the Herald‘s assertions that many had fled from loyal Unionist slaveholders. Yet the newly freed people still faced the daunting tasks of finding food, shelter, and employment. Likely in search of employment, the group lingered around Quincy throughout late March, long enough for the Herald to denigrate their “conduct” and claim that the freed men and women “are now the cause of much excitement and ill-feeling.” With no sympathy for their plight, the paper pointedly asserted that the black Missourians had “forsaken good homes and kind treatment, only to receive the ‘cold shoulder’ from their abolition seducers, and become a burden to themselves and the community in which they intended to locate.” [16]

FURTHER READING

The March 26, 1863 edition of the Hannibal North Missouri Courier reported a stampede of “some thirty or forty American citizens of African descent, owned in and around this city.” However, reports from the two rival Quincy presses provided more detailed descriptions of the escapees, including the Quincy Whig‘s interview with Wash Minter. Those reports suggest that the group numbered around 20 to 25. The most precise account of the freedom seekers actually comes from the Democratic Herald, which identified the affected slaveholders, in the process arriving at a total of 23 enslaved people. [17]

To date, the Hannibal “stampede” for freedom has not been featured in any scholarship.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1863 (ProQuest Historical Newspapers)

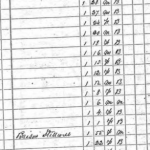

- The enslaved people held by Hannibal slaveholders Robert F. Lakenan and Brison Stillwell were among those who escaped in the March 1863 stampede (Ancestry)

- A bird’s eye view of Hannibal, c. 1869. (Library of Congress)

[1] “Arming the Negroes—‘whither are we Tending?'” and “Democratic Mass Meeting,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, March 24, 1863; “Arming the Negroes–‘Whither Are We Tending?'” Quincy, IL Whig, March 28, 1863; “Slave Stampede,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1863.

[2] “Arming the Negroes—‘whither are we Tending?'” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, March 24, 1863; “Arming the Negroes–‘Whither Are We Tending?'” Quincy, IL Whig, March 28, 1863; “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863.

[3] “Slave Stampede,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1863; “Slave Stampede from Hannibal,” Saint Joseph, MO Weekly Herald, April 2, 1863; “Slave Stampede from Hannibal,” Vincennes (IN) Gazette, April 4, 1863, p. 4; “Slave Stampede from Hannibal,” Lancaster, PA Inquirer, April 6, 1863; “Slave Stampede from Hannibal,” Atchison, KS Freedom’s Champion, April 11, 1863.

[4] “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863; Sarah Carter, “a highly respectable lady,” was the widow of Jesse Carter, who “has been in his grave for years,” noted the Quincy Herald, at least prior to 1860. By the eve of the war, the widowed Carter was living near Hannibal with her son Timoleon. She was identified as the slaveholder of Wash Minter by a column in the Quincy Herald, though the slave schedule in the 1860 U.S. Census lists only three enslaved women held by her, 64, 50 and 40 years in age respectively. See 1850 U.S. Census, Miller Township, Marion County, MO, Family 588, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Miller Township, Marion County, MO, Family 419, Ancestry; 1870 U.S. Census, Miller Township, Marion County, MO, Family 57, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 4, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Ancestry.

[5] “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863; History of Marion County, Missouri (St. Louis, E.F. Perkins, 1884), 2:613-614, [WEB]; 1860 U.S. Census, 3rd Ward, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Family 1258, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]. For the names of the five freedom seekers who escaped from Porter, see Deposition of Aaron R. Levening, July 7, 1863, Marion County Free Negro Records, 1832-1864, Marion County Circuit Court Records, reel C18557, Missouri State Archives.

[6] “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863; 1860 U.S. Census, 3rd Ward, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Family 1158, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[7] “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863; 1860 U.S. Census, 3rd Ward, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Family 1149, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, Hannibal, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]; The most detailed description of the group of freedom seekers, which was provided by the Quincy Herald, identified two escapees from Lakenan and 15 from Mayor Stillwell. However, given that Lakenan held exactly 15 bond people, and Stillwell claimed five, according to the 1860 U.S. Census, it is likely the paper confused the number of escapees from each slaveholder.

[8] “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863; also see Diane Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 268-281.

[9] Gilchrist Porter to John B. Henderson, February 11, 1863, Series 1, General Correspondence, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, [WEB].

[10] Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border, 279-285.

[11] Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border, 285-287.

[12] Porter to Henderson, February 11, 1863, Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, [WEB].

[13] “Arming the Negroes–‘Whither Are We Tending?'” Quincy, IL Whig, March 28, 1863.

[14] “Arming the Negroes—‘whither are we Tending?'” and “Democratic Mass Meeting,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, March 24, 1863; “Arming the Negroes–‘Whither Are We Tending?'” Quincy, IL Whig, March 28, 1863; “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863.

[15] “Arming the Negroes—‘whither are we Tending?'” and “Democratic Mass Meeting,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, March 24, 1863; “Arming the Negroes–‘Whither Are We Tending?'” Quincy, IL Whig, March 28, 1863; “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863.

[16] “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863.

[17] “Slave Stampede,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1863; “Arming the Negroes—‘whither are we Tending?'” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, March 24, 1863; “Arming the Negroes–‘Whither Are We Tending?'” Quincy, IL Whig, March 28, 1863; “The Whig’s N–rs,” Quincy, IL Daily Herald, quoted in St. Louis, MO Republican, March 31, 1863.