Ranking

#5 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

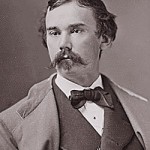

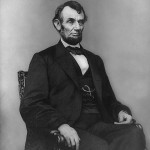

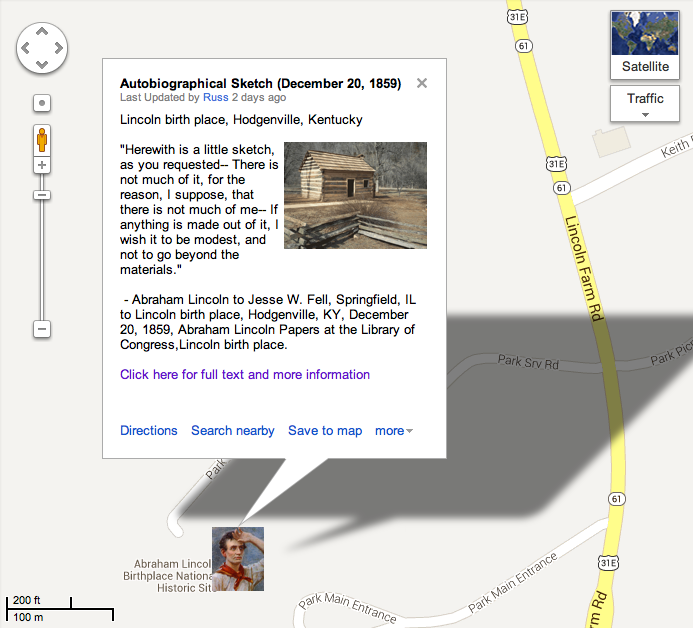

Context. In December 1859, Abraham Lincoln drafted his first extensive autobiographical narrative, a roughly 600-word sketch prepared at the request of an old friend and Republican newspaper editor Jesse W. Fell, who was asking on behalf of a Republican newspaper from Chester County, Pennsylvania that was preparing a series of profiles on the leading contenders for the 1860 Republican presidential nomination. The brief summary became the starting point for subsequent newspaper articles and campaign biographies and illustrates how Lincoln wanted his own story presented to voters in 1860. (By Matthew Pinsker)

“I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky….”

Also now available from the online annotation platform “Poetry Genius”:

Our verified Genius edition transcript

Our Common Core-inspired Genius edition “class” transcript

Audio Version

Recorded by Todd Wronski in January 2011

On This Date

HD Daily Report, December 20, 1859

The Lincoln Log, December 20, 1859

Image Gallery

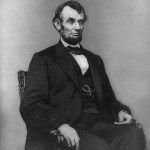

- Lincoln in 1860

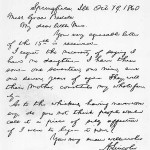

- Image of 1859 letter

- Jesse W. Fell

- Hardin County, Kentucky

- Spencer County, Indiana

- Lincoln as a Rail-Splitter, Illustration

- Lincoln the Rail Splitter, Artist’s Impression

- Lincoln in 1846

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Autobiographical Sketch (1859) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

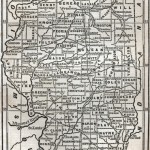

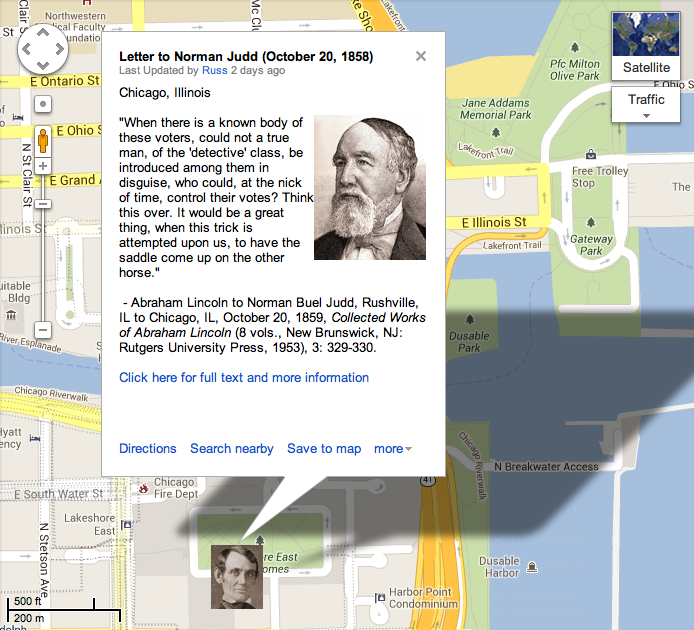

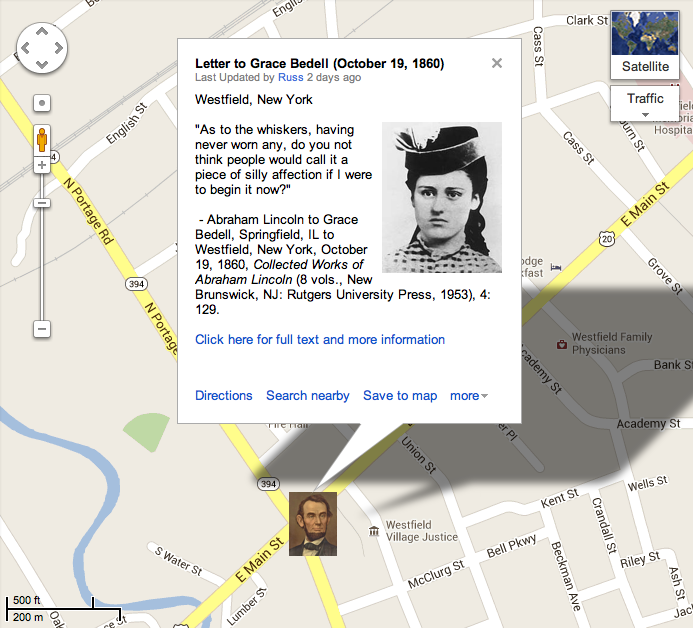

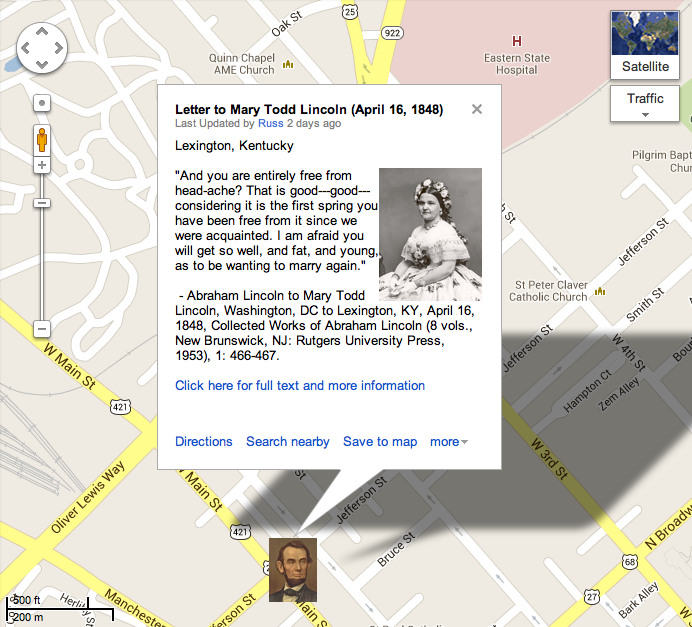

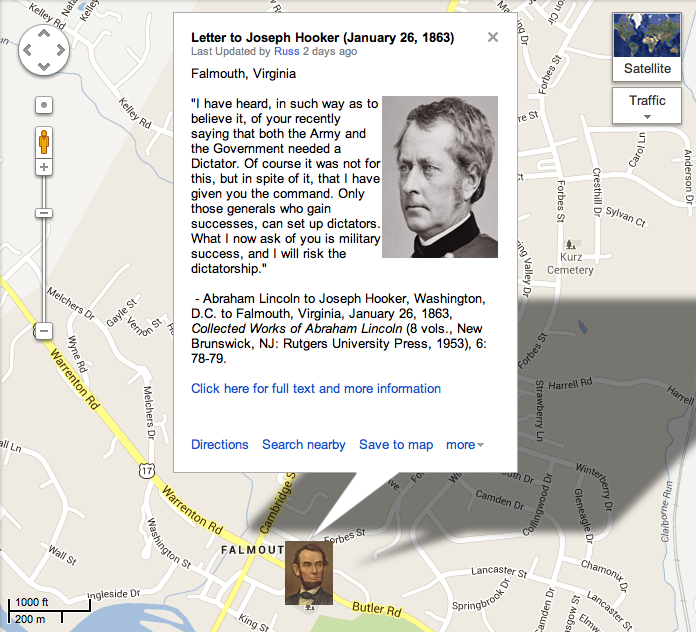

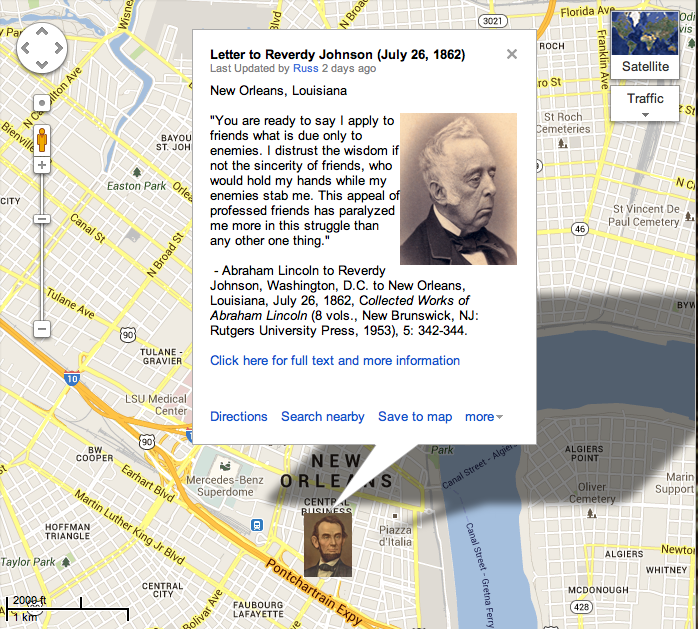

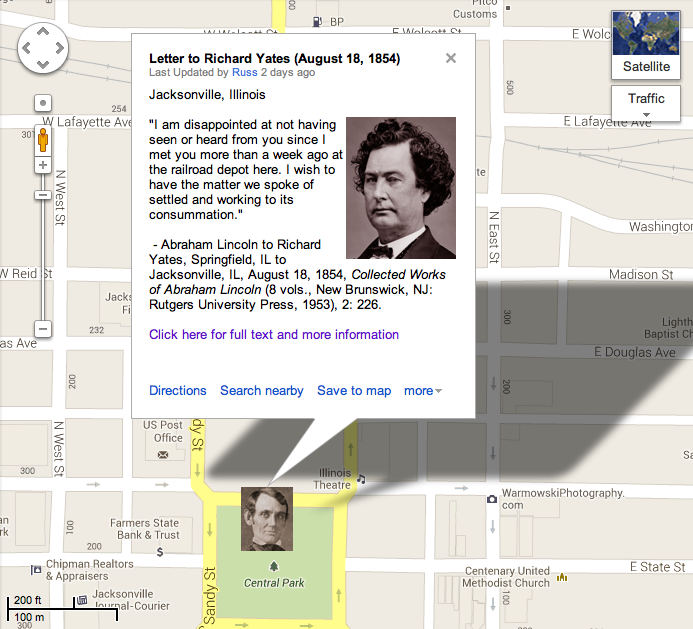

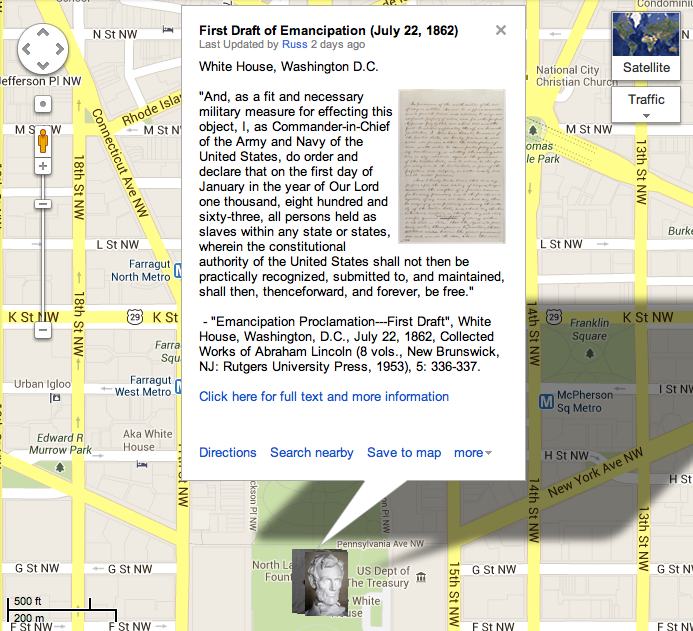

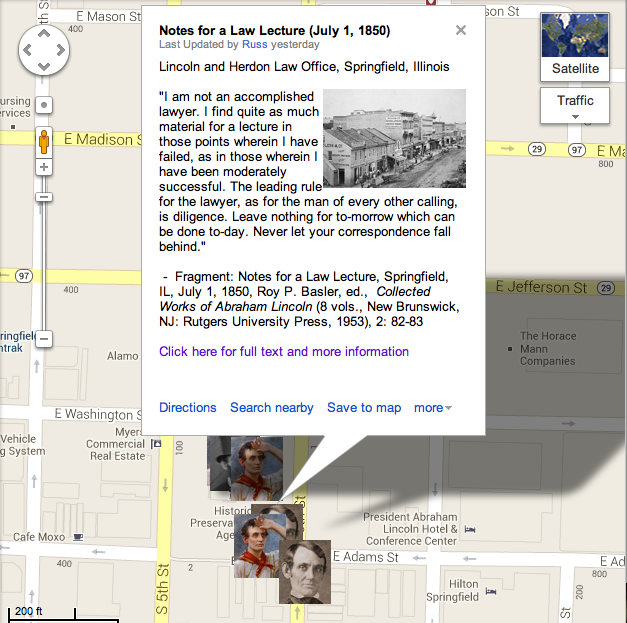

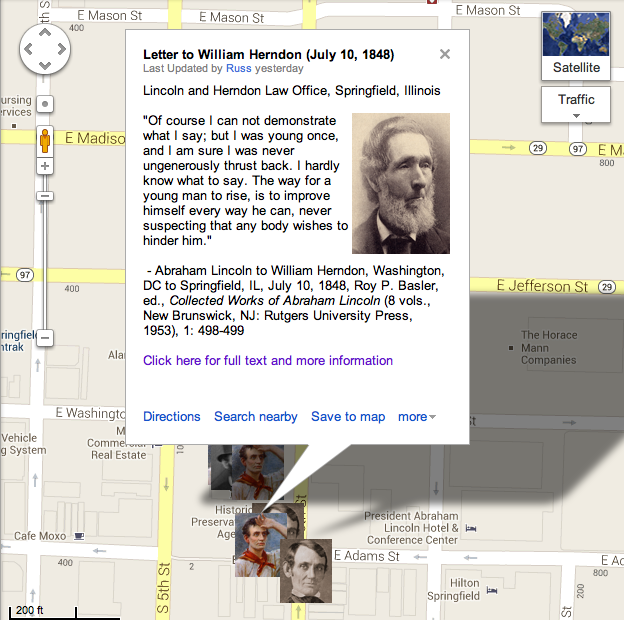

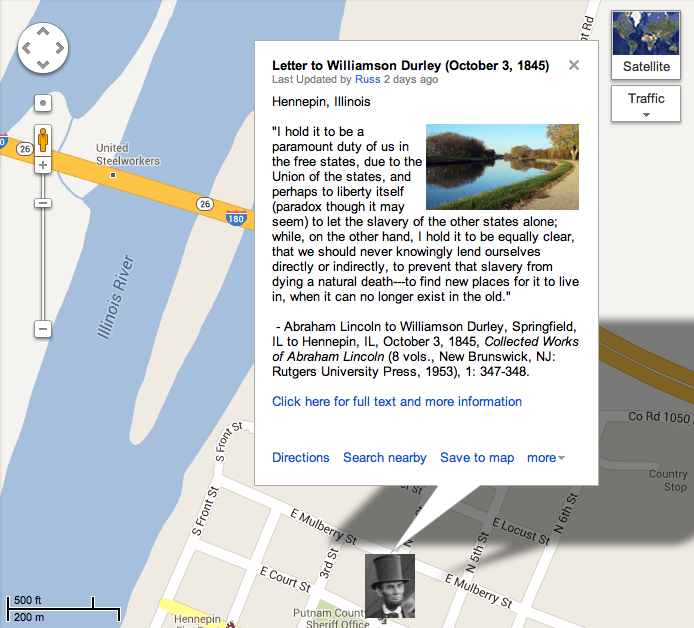

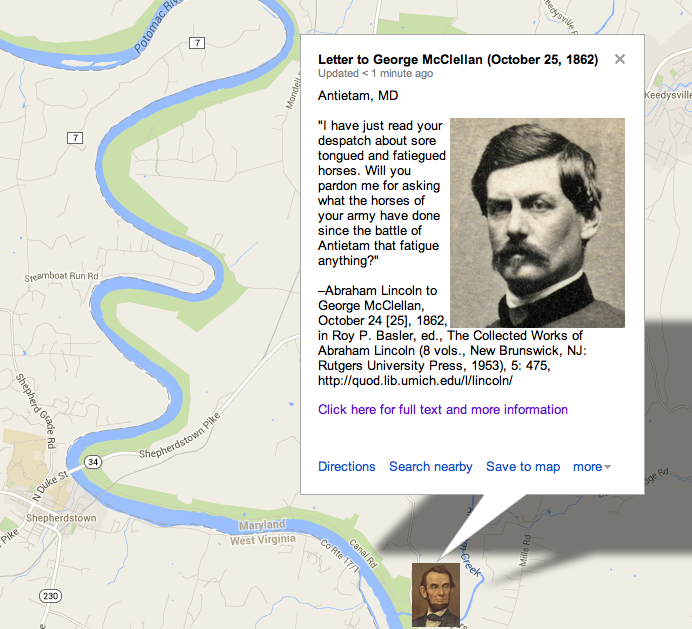

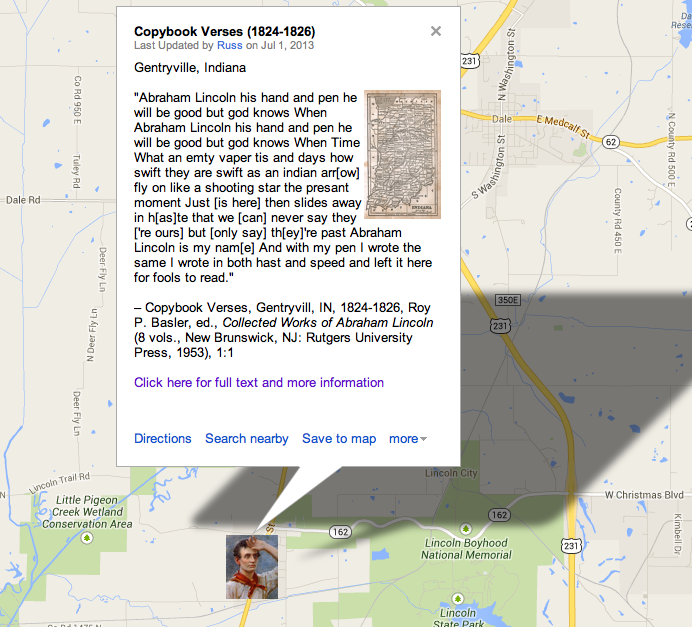

Custom Map

Click on the placemark image above to access the full map

Other Primary Sources

Chester County Times, “Abraham Lincoln,” February 11, 1860

How Historians Interpret

“[Jesse W. Fell] requested an autobiography of Lincoln for use among Eastern voters, who knew little or nothing about Lincoln’s life. The brief and modest autobiography Lincoln sent on December 20 was forwarded immediately to a Pennsylvania friend of Fell’s and was widely reprinted in newspapers in that key state. It is one of the more important sources of information on Lincoln’s family history and early life.”

–Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company: 1980), 108.

“In December 1859, Lincoln made another quiet move to gain broader recognition by preparing an autobiography for campaign purposes. Jesse W. Fell, a Bloomington politician, forwarded a request from Joseph J. Lewis, of the Chester County (Pennsylvania) Times, for biographical information he could use in preparing an article on Lincoln. Lincoln complied with a terse sketch that reviewed his homespun beginnings, summarized his public career, and ended: “If any personal description of me is thought desirable, it may be said, I am, in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing on average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and grey eyes –no other marks or brands recollected.” This he sent to Fell, noting, “There is not much of it, for the reason, I suppose, that there is not much of me.” Lewis evidently found the sketch meager, for he embroidered it with remarks on Lincoln’s oratorical gifts and on his long record of support for a protective tariff, so dear to Pennsylvanians. His article, widely copied in other Republican newspapers, was the first published biography of Lincoln.”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 237

“Early in Lincoln’s senatorial campaign against Stephen A. Douglas, on June 29, 1858, Charles H. Ray of the newly consolidated Chicago Press & Tribune wrote to Lincoln: “We want an autobiography of Abraham Lincoln, the next U. S. Senator from Illinois, to be placed at our discretion, for publication if expedient. ‘A plain unvarnished tale’ is what we would desire. You are the only man who can furnish the facts. To save the imputation of having done it to us, you might give Herndon the points, and he would send them to us. We do not care for a narrative — only a record of dates, place of nativity, parentage, early occupations, trials, disadvantages &c &c — all of which will make, if we are rightly informed, a telling story.” Lincoln’s reply is lost, but it is clear from Ray’s next letter that the candidate demurred. But Ray persisted. In his next letter he wrote: “In my way of thinking, you occupy a position, present and prospectively, that need not shrink from the declaration of an origin ever so humble. If you have been the architect of your own fortunes, you may claim the most merit. The best part of the Lincoln family is not, like potatoes, under the ground. Had you not better reconsider your refusal?” (See Ray to Lincoln, July, 1858). That Lincoln did not reconsider is evident in a letter Ray subsequently sent him in late July from upstate New York: “You will not consider it an unfavorable reflection on your antecedents, when I tell you that you are like Byron, who woke up one morning and found himself famous. In my journey here from Chicago, and now here — one of the most out-of-the-way, rural districts in the State, among a law-going and conservative people, who are further from railroads than any man can be in Illinois — I have found hundreds of anxious enquiries burning to know all about the newly raised up opponent of Douglas — his age, profession, personal appearance and qualities &c &c.” (Ray to Lincoln, July 28, 1858). Whether Lincoln actually relented and yielded to Ray’s repeated requests is not known, but Ray’s initial request — “only a record of dates, place of nativity, parentage, early occupations, trials, disadvantages &c &c” — seems an apt description of the autobiographical statements Lincoln eventually composed. What is clear is that the present document was not Lincoln’s first such attempt. That was written some six months earlier and was sent to Jesse W. Fell on Dec. 20, 1859. (See Abraham Lincoln, Autobiographical Sketch for Jesse W. Fell, December 20, 1859). While it is written in the first, rather than the third person, and is much more succinct than the present statement, it follows a similar outline, and some of its phrases are repeated here.”

—Editors of the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, Note 1, Autobiographical Notes, May-June 1860, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d0321400))

“Abraham Lincoln wrote this ‘little sketch’ of his first fifty years just five months before his nomination to the presidency. He composed it as a research tool for a newspaper feature designed to introduce the still largely unknown western politician to the East. ‘There is not much of it,’ Lincoln apologized in a cover letter, ‘for the reason, I suppose, that there is not much of me.’ Predictably, it was sumptuously embellished when adapted by the Chester County (Pennsylvania) Times on February 11, 1860, even though Lincoln wanted something ‘modest’ that did not ‘go beyond the materials.’ The article was widely reprinted in other pro-Republican organs. But it is the original Lincoln text that remains a principle source of our knowledge about the guardedly private public figure his own law partner complained was ‘the most shut-mouthed man I knew.’ In truth, the sketch rarely travels beyond perfunctory facts toward the realm of insight, and it ends with the vaguest of personal descriptions of the face that would soon become the most recognizable in America. Although he authored more than a million words altogether, Lincoln would produce nothing further about himself except for a slightly longer account of his early days written in 1860 as the basis of a campaign biography. Even though democracy could claim no more convincing validation than his own rise, Lincoln the writer hardly ever illuminated Lincoln the man. Where Lincoln is concerned, history comes no closer to autobiography than this.”

Further Reading

For educators:

- Matthew Pinsker, “Teaching Lincoln’s Autobiography in the Common Core”

- Library of Congress, Questions for Teachers From Lincoln’s Autobiographies

- National Park Service, “Young Abraham Lincoln” (Webrangers Activity for K-8)

For everyone:

- Burlingame, Michael. “Writing Lincoln’s Lives,” multi-media excerpt from Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008), online via Journal Divided, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/journal/2010/10/14/writing-lincolns-lives/

- Sage, Harold K. “Jesse W. Fell and the Lincoln Autobiography,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 3 (1981), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0003.106

Searchable Text

Springfield, Dec: 20. 1859

My dear Sir:

Herewith is a little sketch, as you requested– There is not much of it, for the reason, I suppose, that there is not much of me– If anything is made out of it, I wish it to be modest, and not to go beyond the materials– If it were thought necessary to incorporate any thing from any of my speeches, I suppose there would be no objection– Of course it must not appear to have been written by myself– Yours very truly

A. Lincoln

[ Enclosure:]

I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families — second families, perhaps I should say– My Mother, who died in my ninthtenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks, some of whom now reside in Adams, and others in Macon counties, Illinois– My paternal grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, emigrated from Rockingham County, Virginia, to Kentucky, about 1781 or 2, when, a year or two later, he was killed by indians, not in battle, but by stealth, when he was laboring to open a farm in the forest– His ancestors, who were quakers, went to Virginia from Berks County, Pennsylvania– An effort to identify them with the New-England family of the same name ended in nothing more definite, than a similarity of Christian names in both families, such as Enoch, Levi, Mordecai, Solomon, Abraham, and the like–

My father, at the death of his father, was but six years of age; and he grew up, litterally without education– He removed from Kentucky to what is now Spencer county, Indiana, in my eighth year– We reached our new home about the time the State came into the Union– It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods– There I grew up– There were some schools, so called; but no qualification was ever required of a teacher, beyond the reading, writing, and Arithmetic “readin, writin, and cipherin” to the Rule of Three– If a straggler supposed to understand latin, happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizzard– There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course when I came of age I did not know much– Still somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the Rule of Three, but that was all– I have not been to school since– The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I havehave picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity–

I was raised to farm work, which I continued till I was twenty two– At twenty one I came to Illinois, and passed the first year in Illinois— Macon County — Then I got to New-Salem ( then at that time in Sangamon, now in Menard County, where I remained a year as a sort of Clerk in a store– then came the Black-Hawk war; and I was elected a Captain of Volunteers — a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since– I went the campaign, was elated, ran for the Legislature the same year (1832) and was beaten — the only time I ever have been beaten by the people– The next, and three succeeding biennial elections, I was elected to the Legislature– I was not a candidate afterwards. During this Legislative period I had studied law, and removed to Springfield tomake practice it– In 1846 I was once elected to the lower House of Congress– Was not a candidate for re-election– From 1849 to 1854, both inclusive, practiced law more assiduously than ever before– Always a whig in politics, and generally on the whig electoral tickets, making active canvasses– I was losing interest in politics, when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused me again– What I have done since then is pretty well known —

If any personal description of me is thought desired desirable, it may be said, I am, in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and grey eyes — no other marks or brands recollected–