Teaching the Constitution at War

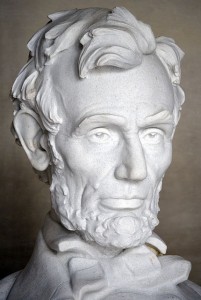

I think the constitution invests its commander-in-chief, with the law of war, in time of war.

Abraham Lincoln, August 26, 1863

By Matthew Pinsker

Abraham Lincoln has long been The Great Example in American history and never more so than whenever presidents claim sweeping war powers in the name of national security. Yet those who invoke Lincoln on behalf of aggressive presidential action should be wary of the precedents which they seek to enshrine, because as much as the great Civil War commander in chief assumed vast power to meet the nation’s gravest crisis, he also set important limits on his own authority. Unfortunately, those limits have been poorly understood or at least distorted in the inevitable partisan bickering that comes with each contested episode of national crisis management. The result has been a debate that often misses the nuances of Lincoln’s measured approach to civil liberties during wartime.

Abraham Lincoln has long been The Great Example in American history and never more so than whenever presidents claim sweeping war powers in the name of national security. Yet those who invoke Lincoln on behalf of aggressive presidential action should be wary of the precedents which they seek to enshrine, because as much as the great Civil War commander in chief assumed vast power to meet the nation’s gravest crisis, he also set important limits on his own authority. Unfortunately, those limits have been poorly understood or at least distorted in the inevitable partisan bickering that comes with each contested episode of national crisis management. The result has been a debate that often misses the nuances of Lincoln’s measured approach to civil liberties during wartime.

Most notably, President Lincoln set four significant limits on his war powers. First, he always argued that presidents should follow the constitutional text and claimed repeatedly that he had done what his oath under Article II had required of him. However, as any good student realizes, the question inevitably becomes one of interpretation. What exactly does it mean to “faithfully execute the office of President,” and how exactly does one “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution”? Yet these interpretive challenges suggested a second limitation for Lincoln. Though he sometimes asserted, like many nineteenth-century political figures, that the three branches of the federal government were co-equal in their abilities to decide  major constitutional questions, Lincoln also respected what this exhibition terms a doctrine for the chronology of powers. In other words, he believed that in times of military crisis, the the separation of powers operated in a certain chronological order that subjected the decisions of a wartime executive to significant constraints imposed after –and not before– major decisions in war-making. Third, Lincoln also believed that even where the commander-in-chief had his widest latitude, such as in the conduct of the war itself and in setting the nation’s grand strategy, he was still bound, however loosely, by the law of war. This international legal limitation has not been well understood, but nonetheless it was a real one for Lincoln. Finally, despite his ardent belief in the value of executive initiative, President Lincoln never ignored or forgot the most important fixed American bulwark in the defense of civil liberties: the election process. “We cannot have free government without elections,” Lincoln said on November 10, 1864. This was a complicated statement coming from someone who believed free government could exist in the face of a wartime suspension of other types of civil liberties. But Lincoln actually meant it, thus offering an expression of extraordinary faith in the principle of popular sovereignty.

major constitutional questions, Lincoln also respected what this exhibition terms a doctrine for the chronology of powers. In other words, he believed that in times of military crisis, the the separation of powers operated in a certain chronological order that subjected the decisions of a wartime executive to significant constraints imposed after –and not before– major decisions in war-making. Third, Lincoln also believed that even where the commander-in-chief had his widest latitude, such as in the conduct of the war itself and in setting the nation’s grand strategy, he was still bound, however loosely, by the law of war. This international legal limitation has not been well understood, but nonetheless it was a real one for Lincoln. Finally, despite his ardent belief in the value of executive initiative, President Lincoln never ignored or forgot the most important fixed American bulwark in the defense of civil liberties: the election process. “We cannot have free government without elections,” Lincoln said on November 10, 1864. This was a complicated statement coming from someone who believed free government could exist in the face of a wartime suspension of other types of civil liberties. But Lincoln actually meant it, thus offering an expression of extraordinary faith in the principle of popular sovereignty.

This exhibition offers a short introduction to Lincoln’s controversial views on war powers and suggests a number of different ways to teach and study them. Not everybody will agree with the interpretations and conclusions offered here, but few could deny that this is a topic of enduring importance and one worth arguing over in many different types of classrooms. Along the four pathways featured below, you will find a number of short essays, videos, and other multi-media resources that help set out various historical arguments about Abraham Lincoln and the contested history of presidential war powers. Please feel free to use any or all of them for educational purposes.

For classroom teachers, we have also created several specific ideas for teaching this topic. Just click on the link below to see a variety of ideas for lesson plans, Common Core units, and other pedagogical approaches.

Also, please don’t be shy about commenting or responding in ways that inject your own views. The greatest example any of us can set is to promote thoughtful debate about topics of profound importance. Just click on the link below to see how others have responded and to share your own ideas.

Finally, this online exhibition “Lincoln and War Powers” has been made possible by a number of generous contributions from institutions and individuals. For a full list of credits and acknowledgements, please click on the link below.