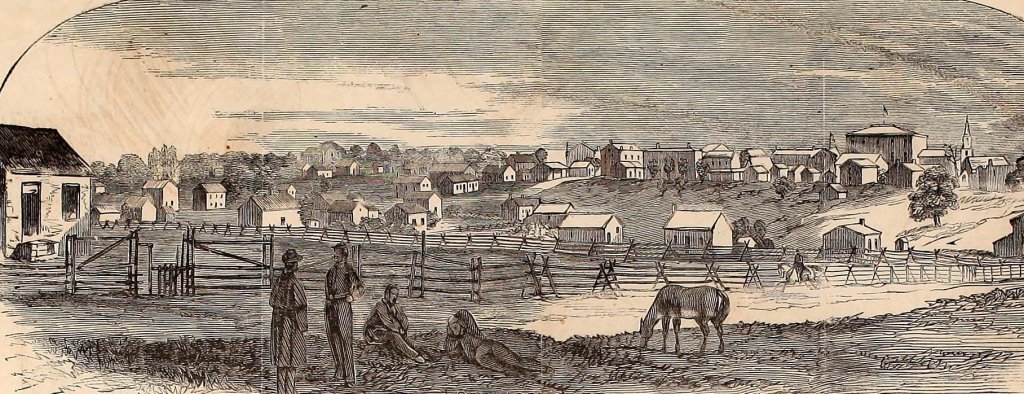

DATELINE: SEPTEMBER 24, 1852, MAYSVILLE, KY

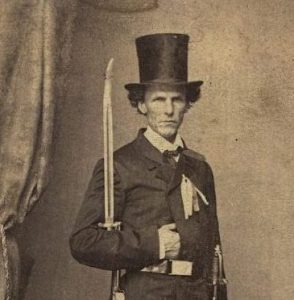

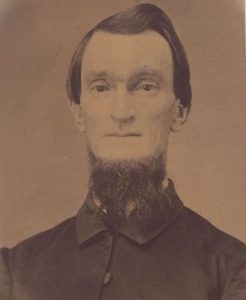

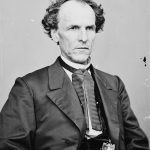

US army general and 1852 Whig presidential nominee Winfield Scott (House Divided Project)

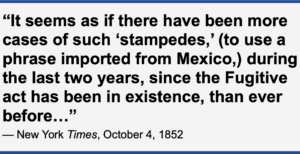

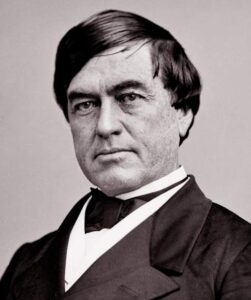

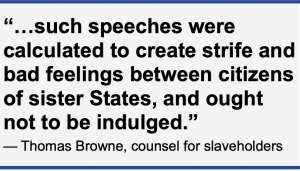

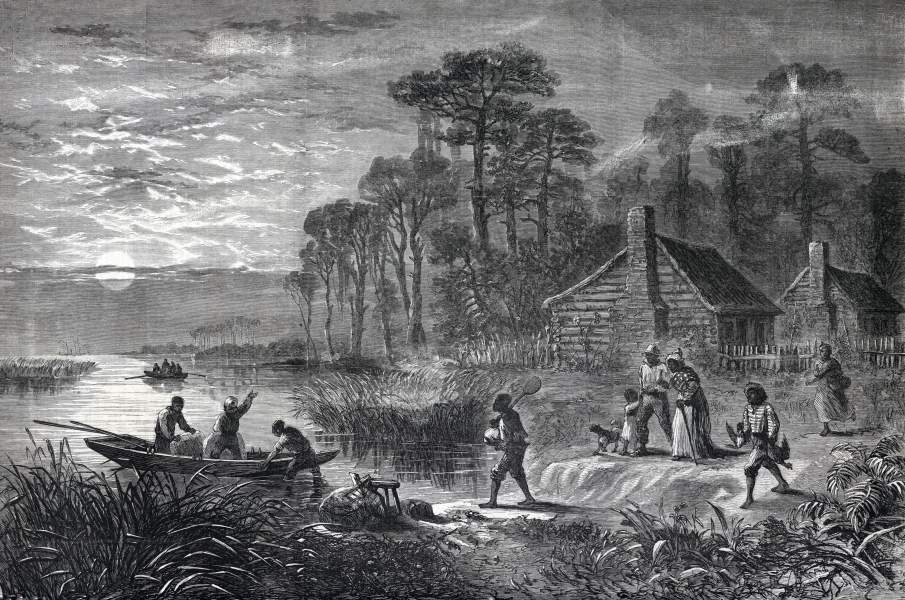

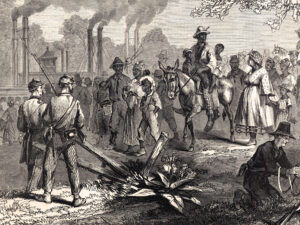

Cannons thundered in salute as Whig presidential candidate Winfield Scott stepped off the dock at Maysville, Kentucky on Friday evening, September 24, 1852. Much like his Democratic rival, Franklin Pierce, Scott aimed to dodge the divisive issue of slavery in hopes of appealing to both Northern and Southern voters. But enslaved Kentuckians had other ideas. Their actions would make avoiding slavery all but impossible during the final weeks of the campaign. While many of their slaveholders traveled to Maysville that weekend and weighed whether to cast their ballots for the Whig nominee, more than 30 enslaved Kentuckians made a political decision of their own when they crossed the Ohio River on Saturday night, September 25 and exited slavery. [1] The latest “slave stampede” from the Kentucky borderlands led to an armed standoff between slaveholders and antislavery vigilance forces in Ripley, Ohio, ratcheting up sectional tensions on the eve of the 1852 presidential election.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

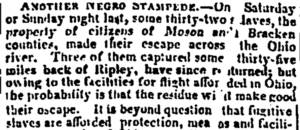

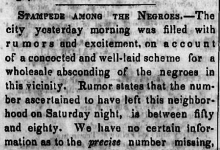

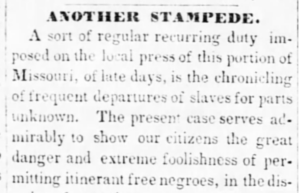

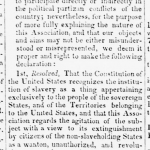

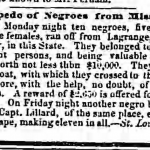

“Another Negro Stampede,” Maysville Eagle, quoted in Louisville (KY) Daily Journal, October 2, 1852 (ProQuest)

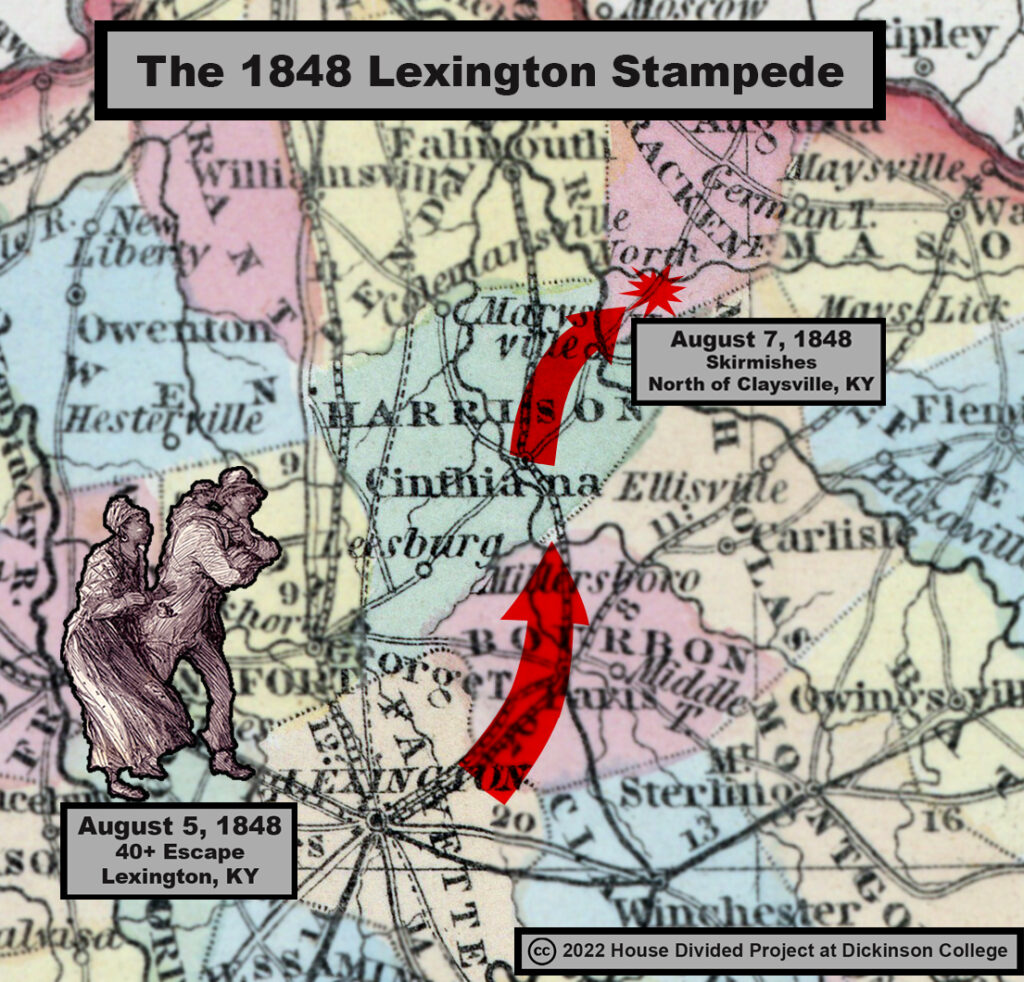

Observers in Kentucky and across the nation were quick to label the mass escape a “stampede.” The headline from nearby Maysville, Kentucky lamented “Another Negro Stampede.” Meanwhile, New York Times and Richmond Enquirer reported on the “Great Slave Stampede” from Kentucky. Writing just days after the escape, Kentucky abolitionist John G. Fee estimated it to be “one of the largest stampedes, perhaps, ever known in the State, and at the same time successful.” [2]

MAIN NARRATIVE

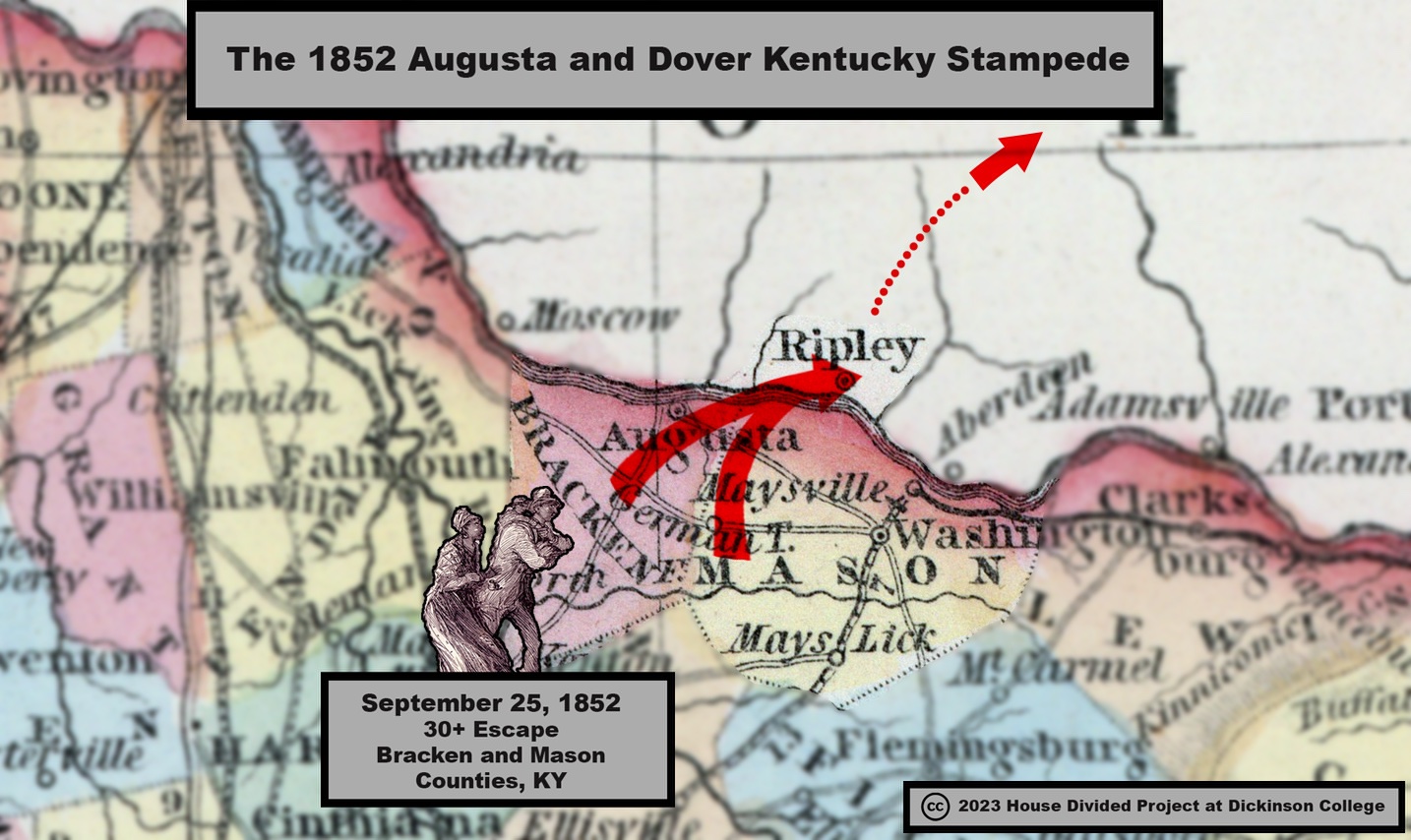

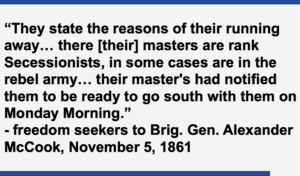

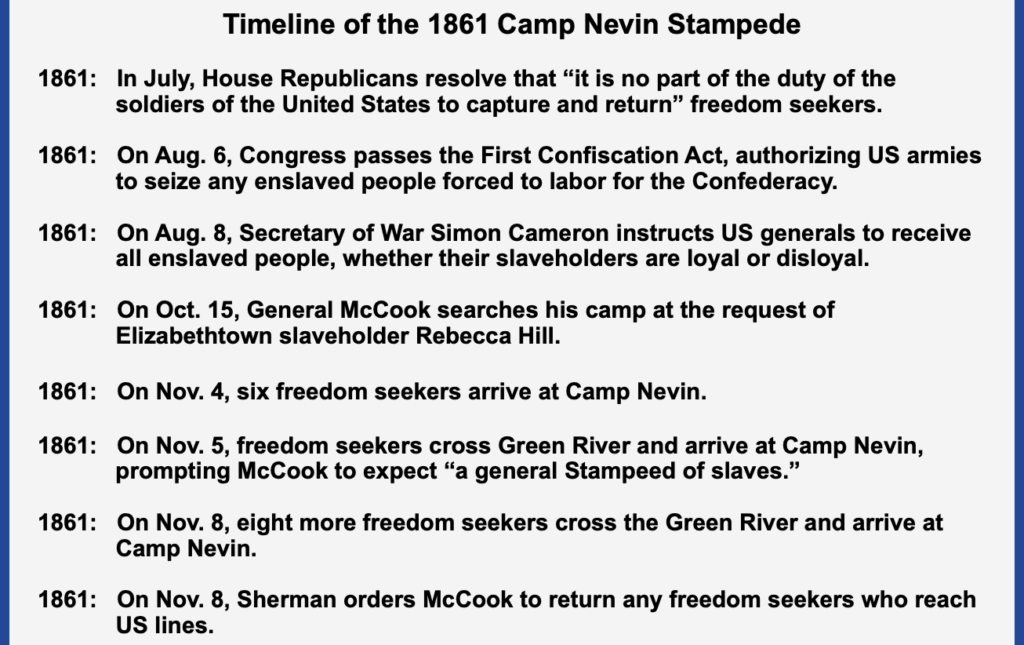

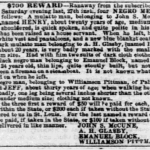

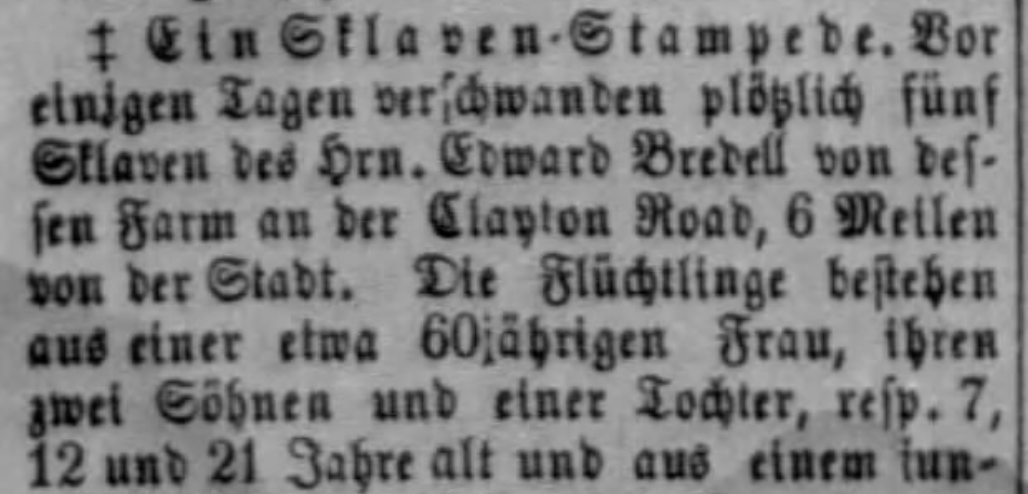

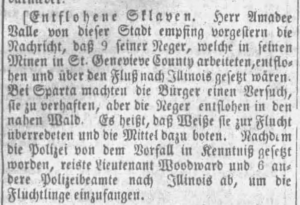

Enslaved people in the border counties of Bracken and Mason correctly anticipated that the political festivities would provide them with an excellent opportunity to escape. After all, Scott’s visit to Maysville was just the highlight of a crowded lineup of political gatherings. Whigs held a convention nearby at Ripley, Ohio, while Scott continued to draw large crowds as he campaigned across northern Kentucky. The political fervor swept up countless white Kentuckians, including many slaveholders who flocked to hear Scott speak. “Their absence, no doubt, afforded the slaves a splendid opportunity to plot and mature their plans for escape,” suggested one Ohio editorialist. More than 30 enslaved people did just that on Saturday evening, September 25, leaving from the riverside towns of Augusta and Dover, Kentucky and crossing the Ohio River to Ripley. [3]

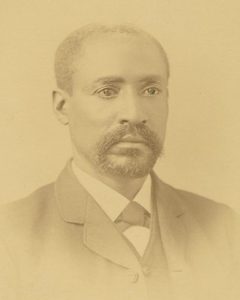

Black abolitionist John Parker assisted freedom seekers from his Ripley, Ohio home, now a museum (Ripley Bee)

It was no accident that the large group of freedom seekers headed straight for Ripley, a riverside community known for its extensive Underground Railroad network. Ripley activists such as Presbyterian minister John Rankin, free Black John Parker, and white miller Thomas McCague regularly assisted freedom seekers. Parker, who later boasted that he had assisted over 400 people across multiple decades, often ventured into Kentucky to personally guide enslaved men and women across the Ohio River to Rankin’s home or McCague’s mill. Parker recalled one daring trip when he piloted a group of freedom seekers from the border counties of Kentucky to McCague’s home, where he instructed them to hide in some hay. This particular group of freedom seekers stood out in Parker’s memory, but not positively. The freedom seekers ignored his repeated pleas to lower their voices and in fact “became so noisy” that Parker and McCague had to relocate the group to McCague’s attic. The veteran abolitionists were “glad to get rid of them as soon as it was dark.” [4]

The unruly freedom seekers whom Parker described may well been those who left Augusta and Dover as part of the September 1852 “stampede,” but his recollection does not provide enough details to say for sure. What is clear is that the freedom seekers from Augusta and Dover reached McCague’s mill by Sunday morning, September 26, very possibly with assistance from Parker. [5]

Once in Ripley, the large group of freedom seekers split over strategy. The majority preferred to stay with McCague and wait until dark the next evening to continue their journey. A smaller contingent of five people insisted on pressing forward immediately. Their decision proved costly. Slaveholders eventually caught up with the smaller group about 35 miles north of Ripley and recaptured three individuals. [6]

Meanwhile, slaveholders had easily traced the larger group of freedom seekers to their hideout in Ripley. Around 2 am on Monday morning, September 27, slaveholders sleuthing around McCague’s mill discovered a bundle of clothing dropped by the freedom seekers. Slaveholders confidently proclaimed that they had “pinned” the runaways. Expecting to recapture the freedom seekers any minute, the Kentuckians requested that their neighbors hurry to Ripley to provide testimony to support their claims in potential legal proceedings. Emboldened by the news, more white Kentuckians streamed into Ripley, “armed to the teeth with double-barrelled shot guns, rifles, pistols, clubs and bowie-knives.” One Kentuckian even crossed the river toting “a carpet sack full of handcuffs.” [7]

Ripley’s free Black community was equally determined to protect the freedom seekers. Black residents armed themselves and laid siege to the hotel where the slave catchers had assembled. With both sides heavily armed, observers worried that the standoff might lead to bloodshed. “Fears are entertained of a serious disturbance,” a correspondent for the New York Herald reported on Monday, September 27 from across the river in Maysville. “The Kentuckians remain there on the watch, and are determined to recover the slaves.” [8]

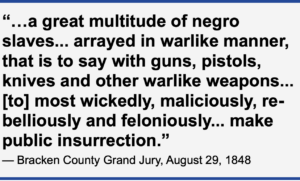

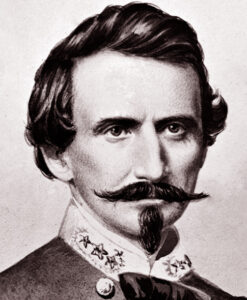

Ripley residents taunted slave catchers with cheers for Free Soil party presidential nominee John P. Hale (House Divided Project)

Ripley’s African American community spearheaded the resistance, though white residents also stonewalled slave catchers’ efforts. Local officials refused to grant slaveholders search warrants to enter McCague’s mill. Although free Black John Parker and several other Ripley abolitionists voluntarily permitted the Kentuckians to search their homes on Monday, September 27, they had no intention of actually assisting the slave catchers. Wherever the freedom seekers were concealed, Ripley abolitionists diverted the slave catchers down what proved to be a series of dead ends. All the while, local residents taunted the Kentuckians after every failed search. “Each failure to make any discovery, was followed with the shout, hurra[h] for Hale,” a barbed reference to the Free Soil party’s presidential candidate, John P. Hale. [9]

By Monday night, slaveholders’ earlier optimism had evaporated. Before long, the Kentuckians headed home empty-handed. The Maysville, Kentucky Eagle ruefully conceded that because of “the facilities for flight afforded in Ohio… the probability is that the residue [of freedom seekers] will make good their escape.” [10]

AFTERMATH

Slaveholders’ anger over the successful stampede put a large target on John Parker’s back. On Friday night, October 1, several Kentuckians attempted to kidnap the veteran abolitionist. Three Kentuckians, George Jennings, Charles Gibbons, and Burn Coburn, waited in a skiff on the river’s edge while they sent an enslaved man named William Carter to Parker’s front door. “I am a runaway, my wife and children are across the river,” Carter explained, pleading with Parker to cross the river with him and help his family escape. Fortunately for Parker, his wife Miranda “intuitively mistrusted the man.” After listening to Carter’s story, Parker agreed that “there was something radically wrong with his story and himself.” Parker pulled a pistol and Carter cracked. The enslaved man admitted that “he was only a decoy, sent by four men” who “were lying behind a log on the riverbank” waiting to seize Parker. One of the would-be kidnappers, Jennings, was Carter’s master, and had “threatened to kill him if he had not come and told the story he did.” [11]

While Parker narrowly avoided kidnappers, observers throughout the country recognized that the latest successful “slave stampede” had the potential to escalate sectional tensions right on the eve of the presidential election. “The escape of the troop of slaves from Kentucky into Ohio, and probably thence to Canada, will be a source of a great irritation in that part of the country,” predicted the Washington correspondent for the New York Times. [12] Kentucky abolitionist minister John G. Fee feared that the state’s nascent antislavery political movement would be blamed for the stampede and was astonished when the Free Soil party’s vice presidential nominee, George W. Julian, was able to campaign unmolested across Mason and Bracken counties only days after the mass escape from those very same counties. “One of the largest stampedes, perhaps, ever  known in the State, and at the same time successful, has just come off,” Fee boasted, “yet no disturbance in our meetings.” Fee thought he had witnessed “a wiping out of Mason and Dixon’s line” and the “partial destruction of the prejudice between North and South.” [13]

known in the State, and at the same time successful, has just come off,” Fee boasted, “yet no disturbance in our meetings.” Fee thought he had witnessed “a wiping out of Mason and Dixon’s line” and the “partial destruction of the prejudice between North and South.” [13]

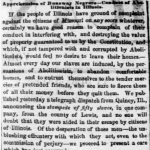

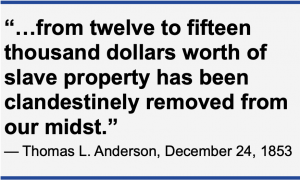

Fee’s hopes for sectional detente proved short-lived, however, because slaveholders in Kentucky and across the South quickly concentrated their ire on Ripley residents who had defied the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act by assisting the freedom seekers. “It is beyond question that fugitive slaves are afforded protection, means and facilities, by people of Ohio, regardless of the obligations and duties devolved on them by the Constitution and Laws of the United States,” complained the Maysville Eagle just days after the standoff in Ripley. The Eagle issued a stern warning to its neighbors across the Ohio River: “the people of Kentucky cannot, will not, and ought not longer to submit to such outrage upon their property rights.” Ripley residents who jeered slave catchers with shouts for Free Soil party presidential candidate John Hale “may laugh now,” the Eagle ominously predicted, “but they will not mock when the Kentuckians, wronged, robbed, outraged, and derided as they have been, shall be roused to vengeance.” [14] The Louisville Courier likewise denounced the “reprehensible” conduct of Ripley officials and reported that “great indignation… pervades the entire community from whence the slaves escaped.” [15] In fact, the resistance in Ripley incited outrage across the South. As far away as Raleigh, North Carolina, a proslavery editor denounced the resistance in Ripley as a “monstrous outrage” and hoped that the Kentuckians would “crush the black armed mob who thus dare to outrage the law of the land.” [16]

Although the stampede did not alter the outcome of the presidential contest––which Democrat Franklin Pierce won handily––it did contribute to the American public’s mounting sense that group escapes were becoming more frequent since the Compromise of 1850. “It seems as if there have been more cases of such ‘stampedes,’ (to use a phrase imported from Mexico,) during the last two years, since the Fugitive act has been in existence, than ever before,” remarked a correspondent for the New York Times. The correspondent attributed the growing trend of group escapes to enslaved people’s realization that a successful escape would require “parties of some force and numbers” who “must go prepared to fight.” [17]

Although the stampede did not alter the outcome of the presidential contest––which Democrat Franklin Pierce won handily––it did contribute to the American public’s mounting sense that group escapes were becoming more frequent since the Compromise of 1850. “It seems as if there have been more cases of such ‘stampedes,’ (to use a phrase imported from Mexico,) during the last two years, since the Fugitive act has been in existence, than ever before,” remarked a correspondent for the New York Times. The correspondent attributed the growing trend of group escapes to enslaved people’s realization that a successful escape would require “parties of some force and numbers” who “must go prepared to fight.” [17]

FURTHER READING

The two most detailed contemporary accounts of the stampede include a report (apparently from a Kentucky newspaper) reprinted at length in a Raleigh, North Carolina newspaper, and a Ripley resident’s account of the confrontation written on October 4 and subsequently published in a Cleveland newspaper. [18] The mass escape has received no sustained coverage in scholarly works to date.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- Ripley abolitionist John Rankin (House Divided Project)

- Abolitionist John G. Fee (House Divided Project)

NOTES

[1] “Gen. Scott in Maysville,” Maysville Eagle, September 25, 1852, quoted in Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, September 28, 1852; “Great Slave Stampede,” New York (NY) Herald, September 29, 1852.

[2] Maysville Eagle, quoted in “Another Negro Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Daily Journal, October 2, 1852; “Great Slave Stampede,” New York (NY) Herald, September 29, 1852; “Stampede of Slaves,” Washington (DC) Daily Republic, September 30, 1852 “Great Slave Stampede,” Richmond (VA) Enquirer, October 1, 1852; “A Stampede of Slaves,” Richmond (VA) Daily Dispatch,October 1, 1852; “Slave Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, October 4, 1852; “Great Slave Stampede,” Raleigh (NC) North Carolina Star, October 6, 1852; “Another Stampede,” Kenosha (WI) Telegraph, October 8, 1852; “Slave Stampede,” Meigs County (OH) Telegraph, October 19, 1852; “Great Slave Stampede,” Natchez (MS) Mississippi Free Trader, October 20, 1852; Rocklin (CA) Placer Herald, November 13, 1852. For Fee’s remark, see “C.M. Clay and Geo. W. Julian,” Washington (DC) National Era, October 14, 1852.

[3] “The Stampede,” Cleveland (OH) Leader, October 14, 1852.

[4] John P. Parker, Stuart Seely Sprague (ed.), His Promised Land: The Autobiography of John P. Parker, Former Slave and Conductor on the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 138-139.

[5] “Great Slave Stampede,” Raleigh (NC) North Carolina Star, October 6, 1852; “The Stampede,” Cleveland (OH) Leader, October 14, 1852.

[6] “Great Slave Stampede,” New York (NY) Herald, September 29, 1852; Maysville Eagle, quoted in “Another Negro Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Daily Journal, October 2, 1852; “Great Slave Stampede,” Raleigh (NC) North Carolina Star, October 6, 1852.

[7] “Great Slave Stampede,” Raleigh (NC) North Carolina Star, October 6, 1852; “The Stampede,” Cleveland (OH) Leader, October 14, 1852.

[8] “Great Slave Stampede,” New York (NY) Herald, September 29, 1852.

[9] “The Stampede,” Cleveland (OH) Leader, October 14, 1852.

[10] Maysville Eagle, quoted in “Another Negro Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Daily Journal, October 2, 1852.

[11] “The Stampede,” Cleveland (OH) Leader, October 14, 1852; Parker, His Promised Land, 146-151. Parker recalled that the attempted kidnapping took place in July, but he was relating the story decades later to a reporter. However, Parker’s account closely matches the description provided in early October 1852 by a Ripley resident (whose letter appeared in a Cleveland newspaper), so much so that I feel confident both accounts refer to the same attempted kidnapping.

[12] “Washington – Flight of Negroes,” New York (NY) Times, October 4, 1852.

[13] “C.M. Clay and Geo. W. Julian,” Washington (DC) National Era, October 14, 1852.

[14] Maysville Eagle, quoted in “Another Negro Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Daily Journal, October 2, 1852.

[15] “Slave Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Daily Courier, October 4, 1852.

[16] “Great Slave Stampede,” Raleigh (NC) North Carolina Star, October 6, 1852.

[17] “Washington – Flight of Negroes,” New York (NY) Times, October 4, 1852.

[18] “Great Slave Stampede,” Raleigh (NC) North Carolina Star, October 6, 1852; “The Stampede,” Cleveland (OH) Leader, October 14, 1852.

To slaveholders, the mass escape had looked alarmingly like a mobile insurrection. Decades later, freedom seeker Harry Slaughter would insist the stampede was not an insurrection, although he acknowledged the freedom seekers’ intention to defend themselves with force if necessary. “The movement was afterwards referred to as an ‘insurrection,’ but it was misnamed,” Slaughter explained. “We did not intend to fight unless attempts were made to capture us, but we pledged ourselves that if we were overtaken by white men and they made an effort to capture us we would fight as long as possible.” [16]

To slaveholders, the mass escape had looked alarmingly like a mobile insurrection. Decades later, freedom seeker Harry Slaughter would insist the stampede was not an insurrection, although he acknowledged the freedom seekers’ intention to defend themselves with force if necessary. “The movement was afterwards referred to as an ‘insurrection,’ but it was misnamed,” Slaughter explained. “We did not intend to fight unless attempts were made to capture us, but we pledged ourselves that if we were overtaken by white men and they made an effort to capture us we would fight as long as possible.” [16]

at, ridiculed and insulted, for making legal and constitutional efforts to capture the flying refugees”–apparently referring to the Chicago

at, ridiculed and insulted, for making legal and constitutional efforts to capture the flying refugees”–apparently referring to the Chicago

drolly commented that “the Sheriff was at least four days behind time.” In nearby Hunstville, Missouri, the editor of the Randolph Citizen expressed what was fast becoming the general consensus: “There seems to be a poor chance for their recovery.”

drolly commented that “the Sheriff was at least four days behind time.” In nearby Hunstville, Missouri, the editor of the Randolph Citizen expressed what was fast becoming the general consensus: “There seems to be a poor chance for their recovery.”

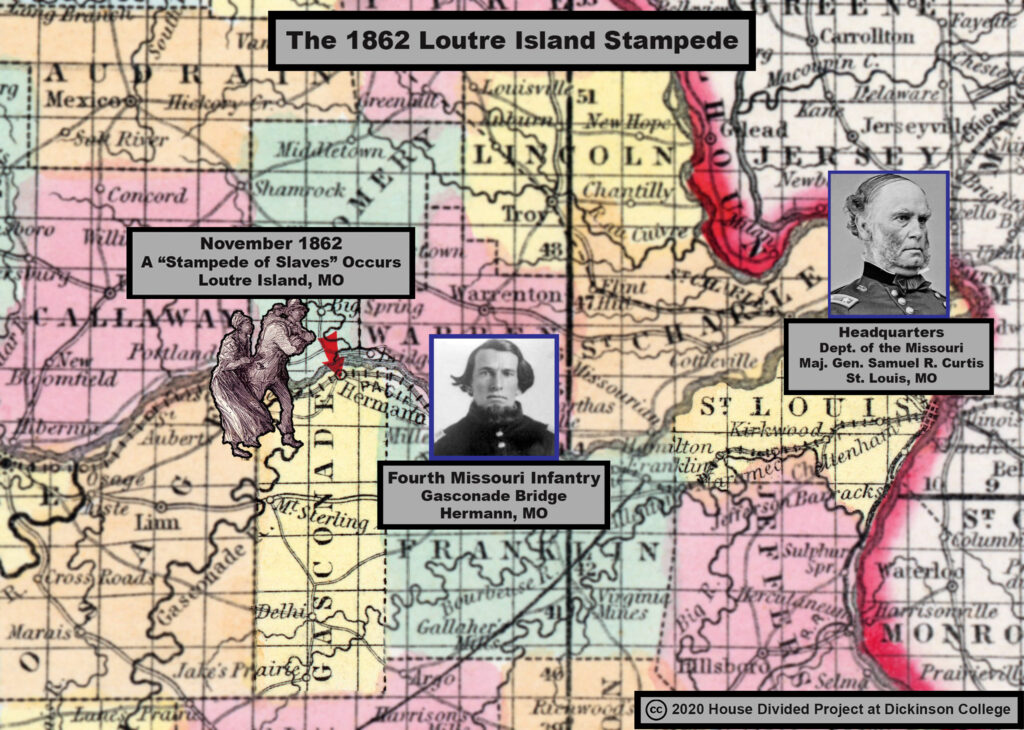

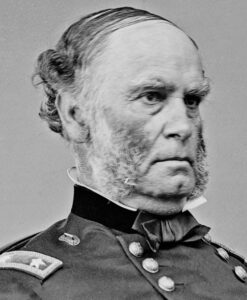

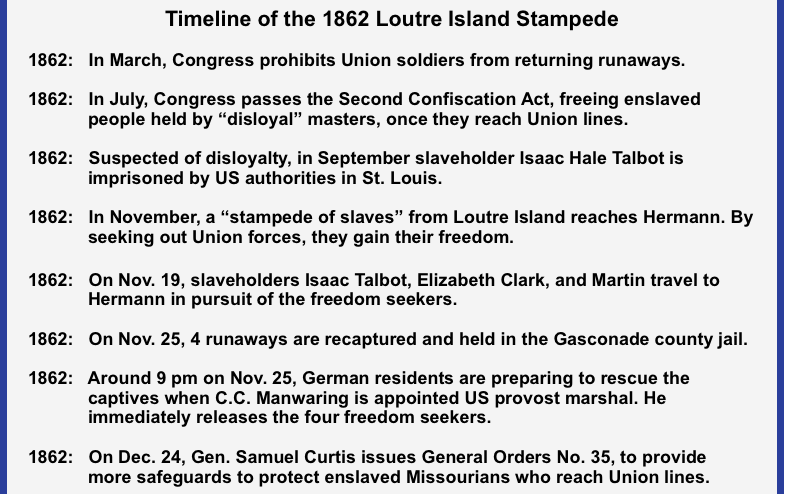

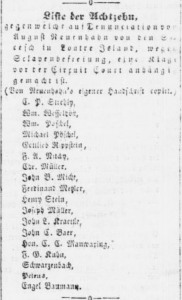

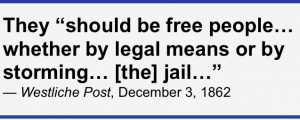

On November 19, not long after Captain Mundwiller permitted the freedom seekers to pass through his lines and ordered them to find work, slaveholders Isaac Talbot, Elizabeth Clark, and Martin travelled to Hermann and sought out the town’s justice of the peace, a Dutch immigrant named John B. Miché. He refused to arrest the freedom seekers under state laws, as the slaveholders insisted he do. Backed by several of the town’s prominent German residents, Miché reasoned that because the state had been under martial law since August 1861, “the matter belonged before the Federal authorities.” Back in St. Louis, the German Westliche Post thundered its approval of Miché’s actions, praising his adherence “to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican.” Undeterred, around a week later the slaveholders cajoled another justice of the peace, a German-born man named Karl Sandberger, to issue the warrants and arrest four freedom seekers, who on Tuesday, November 25 found themselves behind bars at the Gasconade county jail. The news “passed through town and surroundings like wildfire,” wrote one observer, and Hermann’s German population quickly mobilized in protest. By that afternoon, a large crowd had congregated outside the jail, uttering “threats and curses” at the slaveholders and vowing that the captives “should be freepeople” in the morning, “whether by legal means or by storming… [the] jail.”

On November 19, not long after Captain Mundwiller permitted the freedom seekers to pass through his lines and ordered them to find work, slaveholders Isaac Talbot, Elizabeth Clark, and Martin travelled to Hermann and sought out the town’s justice of the peace, a Dutch immigrant named John B. Miché. He refused to arrest the freedom seekers under state laws, as the slaveholders insisted he do. Backed by several of the town’s prominent German residents, Miché reasoned that because the state had been under martial law since August 1861, “the matter belonged before the Federal authorities.” Back in St. Louis, the German Westliche Post thundered its approval of Miché’s actions, praising his adherence “to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican.” Undeterred, around a week later the slaveholders cajoled another justice of the peace, a German-born man named Karl Sandberger, to issue the warrants and arrest four freedom seekers, who on Tuesday, November 25 found themselves behind bars at the Gasconade county jail. The news “passed through town and surroundings like wildfire,” wrote one observer, and Hermann’s German population quickly mobilized in protest. By that afternoon, a large crowd had congregated outside the jail, uttering “threats and curses” at the slaveholders and vowing that the captives “should be freepeople” in the morning, “whether by legal means or by storming… [the] jail.”