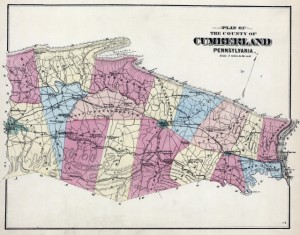

Cumberland County History, a historical journal compiled annually by the Cumberland County Historical Society, has provided nearly three decades of research into the county’s long history. The journal has published several articles on Civil War soldiers from the surrounding community. They utilize several primary documents and effectively offer insight into the emotional departure from loved ones, the lives of soldiers during the war, and the enemy just beyond the Mason-Dixon Line.

Cumberland County History, a historical journal compiled annually by the Cumberland County Historical Society, has provided nearly three decades of research into the county’s long history. The journal has published several articles on Civil War soldiers from the surrounding community. They utilize several primary documents and effectively offer insight into the emotional departure from loved ones, the lives of soldiers during the war, and the enemy just beyond the Mason-Dixon Line.

James A. Holechek features the Civil War experiences of John Cantilion in his article “From Carlisle and Fort Couch: The War of Corporal John A. Cantilion.” By tracing his service in the United States army through to his untimely death in November 1863, Holechek surmises the emotions inherent to leaving loved ones behind as a soldier and, conversely, watching a loved one leave to fight in battle. Letters became the only connection between Cantilion and his wife and children. Accordingly, Holechek used these letters as a window into how the separation affected both parties.

The letters of Lt. Thomas William Sweeny are discussed and provided in part in “Carlisle Barracks –1854-1855: From the Letters of Lt. Thomas W. Sweeny, 2nd Infantry,” edited by Robert Coyer. Sweeny stayed in the Carlisle Barracks for some time during the 1850s before moving to Missouri as a general recruiter for the Union. His time spent in Missouri, as argued by Coyer, “played a major part in keeping the state from seceding.” Most of Coyer’s article centers around several letters he wrote to his wife through 1854 and 1855, part of the time he spent at the Barracks. Though these letters could not note the anguish of separation of loved ones during the war, the tense and difficult relations between the couple become apparent when reading even the first letter.

Patricia M. Coolmeyer collects the perspectives of Civil War soldiers from southern Pennsylvania through the extensive use of personal letters, diaries, and local newspapers. Her article, “Southern Sentiments: A Look at Attitudes of Civil War Soldiers,” illustrates the ways Carlisle, given its geographic proximity to the Mason-Dixon Line, often exchanged its culture and relations with the South. As a result, towns like Carlisle did not uniformly despise the South but rather saw an “active pro-Southern element.” This lack of uniformity emerged in Pennsylvanian soldiers. From one perspective, Union soldiers saw Southerners as “quite a fine looking, gentlemanly set of fellows. Others shaped their perceptions based on the beautiful landscape of the South. Each soldier found different ways to build their allegiance to the Union, but, as Coolmeyer makes clear, it did not always emerge out of a hatred of the South.

The Cumberland County Historical Society has granted us special permission to publish these articles. We encourage readers to utilize their resources, for they have compiled an extensive library filled with primary documents and modern scholarly research. Please consult their website for more information including how to contact the Society.