One hundred fifty years ago today C. P. Kirkland, Jr. wrote home and described his journey from New York City to Washington DC. Kirkland was a member of the 71st New York Infantry and his regiment had been sent to defend Washington DC after the attack on Fort Sumter. The 71st New York had to endure a number of hardships on their trip, including poor quality of food. In New York Kirkland boarded the R. R. Cuyler, which as Kirkland described, “was very filthy, redolent of decayed meat, [and] bilge-water.” The soldiers’ rations were even worse. “The eating was perfectly disgusting – the junk was served out to the men from the hands of the cook,” as Kirkland noted. While he “could not touch it” at first, Kirkland explained that he eventually “reconciled to it” and was now “capable of eating any thing.” After this experience, Kirkland noted that he would never “complain about dirty water, molasses, or any thing else, that may have a few hairs, croton bugs, or any such thing in it.” Yet despite their “sufferings,” Kirkland observed that the men of the 71st New York “are sustained by the conviction that we are actuated by the spirit of a pure and a holy patriotism, and that our course is approved by all the good on earth, and by our Father in Heaven.” After Kirkland’s regiment disembarked in Annapolis, they continued on to Washington DC. You can read Kirkland’s entire letter on House Divided. In addition, you can learn more 71st New York Infantry Regiment from the sources listed on this unit bibliography from the U.S. Army Military History Institute in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

27

Apr

11

C. P. Kirkland’s Journey to Washington, DC

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries25

Apr

11

President Lincoln & the Maryland Legislature

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries Themes: Laws & Litigation One hundred fifty years ago today President Abraham Lincoln wrote General Winfield Scott about what he should do when the Maryland legislature met in Annapolis. While Lincoln had “considered… whether it would not be justifiable… to arrest, or disperse the members of that body,” he concluded that such action “would not be justifiable” since “they have a clearly legal right to assemble.” In addition, Lincoln noted that the United States Government could “not permanently prevent” the Maryland legislature from meeting. If arrested, Lincoln believed that upon their release from prison “they will immediately re-assemble, and take their action.” Yet if the Maryland legislature met and took action against the United States, Lincoln authorized General Scott to respond with force. If Maryland “arm[ed] their people against the United States,” Lincoln instructed Scott “to adopt the most prompt, and efficient means to counteract it, even, if necessary, to the bombardment of their cities.” In addition, Lincoln was also prepared to authorize “the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus” in Maryland. You can read more about the political situation in Maryland in David Detzer’s Dissonance: The Turbulent Days Between Fort Sumter and Bull Run (2006) and in Chapter 23 of Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008).

One hundred fifty years ago today President Abraham Lincoln wrote General Winfield Scott about what he should do when the Maryland legislature met in Annapolis. While Lincoln had “considered… whether it would not be justifiable… to arrest, or disperse the members of that body,” he concluded that such action “would not be justifiable” since “they have a clearly legal right to assemble.” In addition, Lincoln noted that the United States Government could “not permanently prevent” the Maryland legislature from meeting. If arrested, Lincoln believed that upon their release from prison “they will immediately re-assemble, and take their action.” Yet if the Maryland legislature met and took action against the United States, Lincoln authorized General Scott to respond with force. If Maryland “arm[ed] their people against the United States,” Lincoln instructed Scott “to adopt the most prompt, and efficient means to counteract it, even, if necessary, to the bombardment of their cities.” In addition, Lincoln was also prepared to authorize “the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus” in Maryland. You can read more about the political situation in Maryland in David Detzer’s Dissonance: The Turbulent Days Between Fort Sumter and Bull Run (2006) and in Chapter 23 of Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008).

22

Apr

11

After Fort Sumter – William Willey at Dickinson College

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries Themes: Carlisle & Dickinson One hundred fifty years ago today William Willey (Class of 1862) wrote to his father about whether he could remain at Dickinson College and described the conditions in Carlisle as residents prepared for war. Willey lived in western Virginia and his father was serving as a delegate at the Secession convention in Richmond, Virginia. As he told his father, “it is probable that they will not suffer any of us from the South to remain more than a day or two longer.” Willey, however, was not as concerned as other southern students. “The only ones that are in danger are the students from [South Carolina],” as Willey observed. Yet Willey hoped that he could remain at Dickinson College and graduate in 1862. “I will regret it more than any circumstance of my life, should I be compelled to go,” as Willey explained. In addition, Willey’s letter included his observations of Carlisle as residents prepared for war. “The depot is crowded with women bidding adieu to their husbands and sons, and all appear to be mad with excitement,” as Willey described. Carlisle residents even “compelled [Dickinson College] to hoist the stars and stripes,” as Willey noted. You can listen to this letter by clicking on the play button below:

One hundred fifty years ago today William Willey (Class of 1862) wrote to his father about whether he could remain at Dickinson College and described the conditions in Carlisle as residents prepared for war. Willey lived in western Virginia and his father was serving as a delegate at the Secession convention in Richmond, Virginia. As he told his father, “it is probable that they will not suffer any of us from the South to remain more than a day or two longer.” Willey, however, was not as concerned as other southern students. “The only ones that are in danger are the students from [South Carolina],” as Willey observed. Yet Willey hoped that he could remain at Dickinson College and graduate in 1862. “I will regret it more than any circumstance of my life, should I be compelled to go,” as Willey explained. In addition, Willey’s letter included his observations of Carlisle as residents prepared for war. “The depot is crowded with women bidding adieu to their husbands and sons, and all appear to be mad with excitement,” as Willey described. Carlisle residents even “compelled [Dickinson College] to hoist the stars and stripes,” as Willey noted. You can listen to this letter by clicking on the play button below:

Listen to William Willey’s letter:

20

Apr

11

Aftermath of the Baltimore Riot

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & Soldiers One hundred fifty years ago today Mayor George W. Brown wrote Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew and described the riot that took place the previous day in Baltimore, Maryland. The Sixth Massachusetts Regiment had left Philadelphia in the morning of April 19, 1861, but while crossing the between the President Street and the Camden railroad depots in Baltimore they were attacked in the streets by southern sympathizing rioters. The Sixth Massachusetts reached their Washington-bound train but not before they had suffered three killed and others wounded and opened fire in response, killing thirteen rioters. “Our people viewed the passage of armed troops to another State through the streets as an invasion of our soil, and could not be restrained,” as Mayor Brown explained. As “all communication between this city and…Boston by steamers [had] ceased,” Brown noted that “the bodies of the Massachusetts soldiers” had to remain in Baltimore and that they were “placed with proper funeral ceremonies in the mausoleum of Greenmount Cemetery.” Governor Andrew later replied that he was “overwhelmed with surprise that a peaceful march of American citizens over the highway to the defence of our common capital should be deemed aggressive to Baltimoreans.” You can read more about the Baltimore riot in David Detzer’s Dissonance: The Turbulent Days Between Fort Sumter and Bull Run (2006).

One hundred fifty years ago today Mayor George W. Brown wrote Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew and described the riot that took place the previous day in Baltimore, Maryland. The Sixth Massachusetts Regiment had left Philadelphia in the morning of April 19, 1861, but while crossing the between the President Street and the Camden railroad depots in Baltimore they were attacked in the streets by southern sympathizing rioters. The Sixth Massachusetts reached their Washington-bound train but not before they had suffered three killed and others wounded and opened fire in response, killing thirteen rioters. “Our people viewed the passage of armed troops to another State through the streets as an invasion of our soil, and could not be restrained,” as Mayor Brown explained. As “all communication between this city and…Boston by steamers [had] ceased,” Brown noted that “the bodies of the Massachusetts soldiers” had to remain in Baltimore and that they were “placed with proper funeral ceremonies in the mausoleum of Greenmount Cemetery.” Governor Andrew later replied that he was “overwhelmed with surprise that a peaceful march of American citizens over the highway to the defence of our common capital should be deemed aggressive to Baltimoreans.” You can read more about the Baltimore riot in David Detzer’s Dissonance: The Turbulent Days Between Fort Sumter and Bull Run (2006).

Listen to Mayor George Brown’s letter to Governor John Andrew:

Listen to Governor John Andrew’s reply to Mayor George Brown:

11

Mar

11

President James Buchanan’s Administration

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries, Places to Visit Themes: Contests & Elections, Laws & Litigation One hundred fifty years ago today James Buchanan was at his home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and wrote a letter to New York Herald editor James Gordon Bennett in which he reflected on his administration. The Herald, as Buchanan explained, had provided “able & powerful support…almost universally throughout my stormy and turbulent administration.” Yet overall Buchanan saw his administration as a success. “Under Heaven’s blessing the administration has been eminently successful in its foreign & domestic policy,” Buchanan noted. As for “the sad events which have recently occurred” during the secession crisis, Buchanan argued that “no human wisdom could have prevented” them. While “I feel conscious that I have done my duty,” Buchanan acknowledged that it “will be for the public & posterity to judge” if he had provided “wise & peaceful direction towards the preservation or reconstruction of the union.” After the Civil War, Buchanan continued to defend his administration’s policies in Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion (1866).

One hundred fifty years ago today James Buchanan was at his home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and wrote a letter to New York Herald editor James Gordon Bennett in which he reflected on his administration. The Herald, as Buchanan explained, had provided “able & powerful support…almost universally throughout my stormy and turbulent administration.” Yet overall Buchanan saw his administration as a success. “Under Heaven’s blessing the administration has been eminently successful in its foreign & domestic policy,” Buchanan noted. As for “the sad events which have recently occurred” during the secession crisis, Buchanan argued that “no human wisdom could have prevented” them. While “I feel conscious that I have done my duty,” Buchanan acknowledged that it “will be for the public & posterity to judge” if he had provided “wise & peaceful direction towards the preservation or reconstruction of the union.” After the Civil War, Buchanan continued to defend his administration’s policies in Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion (1866).

16

Feb

11

Lincoln Meets Grace Bedell

Posted by Matthew Pinsker Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Contests & Elections, Women & FamiliesJust 150 years ago today on Saturday afternoon, February 16, 1861, President-Elect Abraham Lincoln met twelve-year-old Grace Bedell on a train platform in Westfield, New York. Showing off his new facial hair, he kissed the young girl and reportedly said, ““You see I have let these whiskers grow for you, Grace.”

If you know this story, then you’re either a Civil War buff or a very attentive sixth-grader. The year before Grace Bedell had written presidential candidate Abe Lincoln (whom she addressed as “Hon. A.B. Lincoln”) in October 1860 from her family’s temporary residence in upstate New York, inquiring whether Lincoln had any daughters before urging him to “let your whisker grow” since “your face is so thin.” This is a charming story that many elementary school teachers describe in their classrooms because it conveys such an important message about empowerment. Young Grace had an endearing, childlike candor (“answer this letter right off” she wrote in closing) that apparently ignited the bored candidate’s fancy because he responded within days. “I regret the necessity of saying I have no daughters,” Lincoln replied, adding, “As to the whiskers, having never worn any, do you not think people would call it a piece of silly affectation if I were to begin it now?” The famous letters, however, have never before been exhibited in public until 2009 when they were brought together by the Library of Congress in an exhibition that is currently traveling around the country.

In Lincoln’s era, presidential candidates almost always stayed home and avoided making public statements. It was considered undignified and un-republican to seek the presidential office. Obviously a few things have changed, but at least one political truth has endured. Image mattered just as much then as now.

Most school children hear this much of the Lincoln-Bedell story at least once during their academic careers, and every Lincoln scholar knows about it. But until recently, nobody really believed there was any more to the relationship. After the war, Grace Bedell married a Union army veteran named George Billings. The couple moved to Kansas and forged a life on the western prairie. They had one son and no daughters. Every so often until her death in 1936, Grace Bedell Billings would make an appearance, consent to an interview, or respond to some new correspondent seeking details about her encounter with Lincoln. Yet the gun-toting homesteader seemed mostly indifferent to her recurring fifteen minutes of fame. Grandson George Billings wrote to Time magazine shortly after her death, thanking the editors for orchestrating a dramatization about her experience with Lincoln, and claiming credibly that one of her favorite expressions had always been, “I dislike making a fuss.” Today, Billings descendants are trying to raise funds to preserve her former home in Delphos, Kansas.

This effort received a boost in 2007 when a diligent Lincoln researcher named Karen Needles discovered a new letter from Grace Bedell to President Lincoln that was written in January 1864 and somehow had gotten overlooked in the voluminous files of the National Archives. “Do you remember before your election receiving a letter from a little girl residing at Westfield in Chautauqua Co. advising the wearing of whiskers as an improvement to your face,” Bedell asked, before informing the president in firm, clear handwriting, “I am that little girl grown to the size of a woman.” Young Grace had grown but her characteristic brashness remained. Reminding the president that he had signed his previous letter to her, “Your true friend and well-wisher,” Bedell asked, “Will you not show yourself my friend now?” It turned out that she wanted a job, but her reason was quite poignant. “My Father during the last few years lost nearly all his property,” she confided, “and although we have never known want, I feel that I ought and could do something for myself.” She had heard about “a large number of girls” who were “employed constantly and with good wages at Washington cutting Treasury notes and other things pertaining to that Department.” She wondered, “Could I not obtain a situation there?” The appeal closed by noting that her parents were “ignorant of this application” and gently pointing out that she had sent an earlier query to him that had gone unanswered. “Direct to this place” was the line that closed Grace Bedell’s third letter to Abraham Lincoln.

She never heard back from the president and never once mentioned this application in any of her post-war accounts. Yet there is some reason to believe that President Lincoln did respond to Grace’s request by writing to her parents directly. There have been many children’s books written about Grace Bedell, and most are inconsequential, but there has been one serious historical account produced by Fred Trump, a native of Westfield who ended up settling in Salina, Kansas, not far from the Billings farm in Delphos. That coincidence apparently drove Trump, a retired Department of Agriculture official, to prodigious effort in his research. He turned up many local accounts that appear nowhere else but in his 1977 book, Lincoln’s Little Girl.

Toward the end of his book, Trump relates how some members of the Bedell family claimed that President Lincoln tried to adopt Grace during the war. The author quoted from multiple accounts produced by a woman named Jennie Macomber, who had been a little girl herself in Westfield in 1860 and who later befriended members of the Bedell family. She recalled how they told her that the president had written Grace’s father during the war “and offered to adopt her as his own daughter.” Trump believed Macomber’s story, and corroborated it as much as he could, but also dutifully quoted several Lincoln experts who coolly dismissed the tale as “embroidery.” The late Roy P. Basler, editor of Lincoln’s Collected Works, informed Trump, “The Abraham Lincoln papers include no correspondence between Lincoln and the parents of Grace Bedell. The collections in this division are not known to contain any information corroborating this story.”

That was in 1977. But in 2007, there appeared this newly discovered letter that does offer at least some corroboration of the old family gossip. After reading the 1864 letter from Grace, it is easy to imagine that Abraham Lincoln responded to the story of the Bedell family’s financial struggles with a direct appeal to Grace’s father. The president might well have offered to have the young woman live in the White House while she worked as one of the war’s many Treasury Department girls. Too proud to admit his financial reversals, businessman Norman Bedell either declined or just ignored the unexpected offer. What seemed fanciful to Roy Basler, now appears more reasonable given this new letter. Of course, the irony is that like so much else in history, with more information, our certainty about the past suddenly seems far less secure.

19

Jan

11

Civil War Soldier Correspondence

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & SoldiersSoldier Studies is a free online database that contains over 1200 Union and Confederate soldiers’ letters between 1860 and 1865. Each soldier has a profile with key biographical information and links to all of their letters in the collection. Some profiles also include photographs and short essays about the soldier. For example, Soldier Studies has four letters by Henry H. Hitchcock, who served in Company A of the 12th New York. In June 1861 Hitchcock’s regiment was in Washington DC. After he saw the “post office, treasury building, White House, Smithsionian Institute, [and] the Washington Monument,” Hitchcock explained that he “never saw too much before in so short a time” and “had no idea of the splendor of the public buildings here.” You can also browse this collection by subject, search by keyword, or see the full list of soldiers’ who have profiles. Check this page for the latest updates to the site. In addition, Soldier Studies has several resources available for teachers, such as the “American Civil War Soldier WebQuest.” The site also has a collection of articles on a number of different topics, including “Caring for the Men: The History of Civil War Medicine” and “Civil War Pensions.” Soldier Studies was created by Chris Wehner, a high school history teacher in Colorado, and Devin Watson.

13

Dec

10

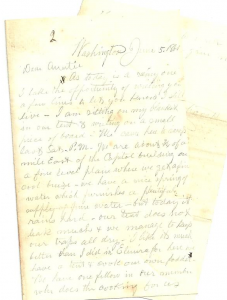

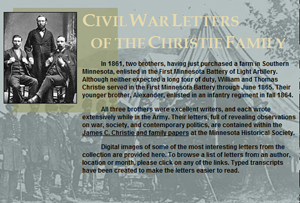

Civil War Letters of the Christie Family

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries, Recent Scholarship Themes: Battles & SoldiersThe Civil War Letters of the Christie Family at the Minnesota Historical Society offer an interesting perspective from three brothers who served in the Union army. Thomas and William Christie, who were both born in Ireland, enlisted in the First Minnesota Battery in 1861 and participated in the Vicksburg campaign as well as General William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea. Thomas had no difficulty in adjusting to “military life,” but noted that other soldiers in his regiment apparently found the transition to be a difficult one. “A great many of our men — and the Americans especially — cannot leave off those habits of Independence, which are so meritorious in the civilian, but so pernicious in the Soldier,” as Thomas observed. While they described their experiences during the war in detail, they also commented on contemporary political issues. William identified slavery as the cause of the conflict and supported President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. “For lighting the torch of Freedom,” William wrote that “the oppressed thoughout the land are this day Praying God to give us the victory.” Alexander, however, did not enlist until late 1864. After several months of training, his infantry regiment arrived in North Carolina in early April 1865 to participate in what he considered “the last great forward advancement of Sherman’s Army.”

In December 2010 the Minnesota Historical Society published a collection of these letters — Hampton Smith, Brother of Mine: The Civil War Letters of Thomas and William Christie (2010). “The letters are so engaging that one longs for more,”as a review in the Minneapolis – St. Paul Star Tribune notes. You can read the full review here.

10

Dec

10

Isaac L. Taylor at Gettysburg

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & Soldiers On July 2, 1863 at 5:40AM Isaac Taylor recorded in his diary that his regiment, the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, had arrived at Gettysburg. “Order from Gen. [John] Gibbon read to us in which he says this is to be the great battle of the war & that any soldier leaving ranks without leave will be instantly put to death,” as Taylor noted. By the end of the day 215 of the 262 soldiers in the regiment had been killed or wounded. While Isaac died, his brother, Patrick Henry Taylor, made it out of the battle without injury. After Patrick buried his brother, he added the final entry to the diary – Isaac had been “killed by a shell about sunset” and his grave was located “[about] a mile South of Gettysburg.” Four other Taylor brothers also served in other Union regiments during the Civil War. While Jonathan (Second Minnesota Battery of Light Artillery), Danford (Twelfth Illinois Cavalry), and Samuel (102nd Illinois Infantry) survived the war, Judson was in Company K of the Eleventh Illinois Cavalry when he died at Vicksburg on December 1, 1864. Isaac’s Taylor’s diary was published in the Minnesota History Magazine in 4 sections. You can download them as a PDF file: Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 3 ; Part 4. Several historians have studied the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry, including John Quinn Imholte’s The First Volunteers; History of the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment, 1861-1865 (1963), Richard Moe’s Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers (1993), and Brian Leehan’s Pale Horse at Plum Run: The First Minnesota at Gettysburg (2004). You can read another account of the regiment’s actions in James A. Wright’s No More Gallant a Deed: a Civil War Memoir of the First Minnesota Volunteers (2001).

On July 2, 1863 at 5:40AM Isaac Taylor recorded in his diary that his regiment, the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, had arrived at Gettysburg. “Order from Gen. [John] Gibbon read to us in which he says this is to be the great battle of the war & that any soldier leaving ranks without leave will be instantly put to death,” as Taylor noted. By the end of the day 215 of the 262 soldiers in the regiment had been killed or wounded. While Isaac died, his brother, Patrick Henry Taylor, made it out of the battle without injury. After Patrick buried his brother, he added the final entry to the diary – Isaac had been “killed by a shell about sunset” and his grave was located “[about] a mile South of Gettysburg.” Four other Taylor brothers also served in other Union regiments during the Civil War. While Jonathan (Second Minnesota Battery of Light Artillery), Danford (Twelfth Illinois Cavalry), and Samuel (102nd Illinois Infantry) survived the war, Judson was in Company K of the Eleventh Illinois Cavalry when he died at Vicksburg on December 1, 1864. Isaac’s Taylor’s diary was published in the Minnesota History Magazine in 4 sections. You can download them as a PDF file: Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 3 ; Part 4. Several historians have studied the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry, including John Quinn Imholte’s The First Volunteers; History of the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment, 1861-1865 (1963), Richard Moe’s Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers (1993), and Brian Leehan’s Pale Horse at Plum Run: The First Minnesota at Gettysburg (2004). You can read another account of the regiment’s actions in James A. Wright’s No More Gallant a Deed: a Civil War Memoir of the First Minnesota Volunteers (2001).

19

Nov

10

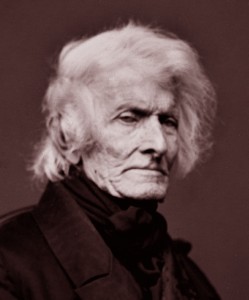

Election of 1860 – William Wilkins Letter

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Carlisle & Dickinson, Contests & Elections William Wilkins’ letter to James Webb, editor and publisher of the New York Courier and Enquirer, reveals an interesting view on some of the political perspectives that existed on the eve of the 1860 election. Wilkins, who graduated from Dickinson College in 1802, was a Pennsylvania Democratic politician who also served as Secretary of War in President John Tyler’s administration. While Wilkins had originally “intended to have told you something of myself,” he noted that Webb’s political “pamphlet has driven all such things out of my head and set if off ‘a wool gathering.’” Wilkins’ was not happy with Webb’s take on slavery. George Washington “never dreaming he was fighting for kidnapped Africans of the Lowest order of human beings,” Wilkins argued. Wilkins also believed that southerners should be allowed to bring slaves into any territory. “Where is the great right of migration?,” Wilkins asked. Yet Wilkins was careful to note that he did not count Webb among the radical abolitionists. “You must not suppose I include you…in [the] certain mad, fanatical category as full of political wickedness as was John Brown,” Wilkins explained. Wilkins hoped that sectional tensions would be resolved without resorting to disunion, as there could be no “secession, without pulling down the entire wonderfully and wildly constructed fabric” of the Union. While Wilkins’ wife asked him “to burn…this horrible letter,” he refused and sent it onto Webb. You can read the full text of this letter online at House Divided.

William Wilkins’ letter to James Webb, editor and publisher of the New York Courier and Enquirer, reveals an interesting view on some of the political perspectives that existed on the eve of the 1860 election. Wilkins, who graduated from Dickinson College in 1802, was a Pennsylvania Democratic politician who also served as Secretary of War in President John Tyler’s administration. While Wilkins had originally “intended to have told you something of myself,” he noted that Webb’s political “pamphlet has driven all such things out of my head and set if off ‘a wool gathering.’” Wilkins’ was not happy with Webb’s take on slavery. George Washington “never dreaming he was fighting for kidnapped Africans of the Lowest order of human beings,” Wilkins argued. Wilkins also believed that southerners should be allowed to bring slaves into any territory. “Where is the great right of migration?,” Wilkins asked. Yet Wilkins was careful to note that he did not count Webb among the radical abolitionists. “You must not suppose I include you…in [the] certain mad, fanatical category as full of political wickedness as was John Brown,” Wilkins explained. Wilkins hoped that sectional tensions would be resolved without resorting to disunion, as there could be no “secession, without pulling down the entire wonderfully and wildly constructed fabric” of the Union. While Wilkins’ wife asked him “to burn…this horrible letter,” he refused and sent it onto Webb. You can read the full text of this letter online at House Divided.