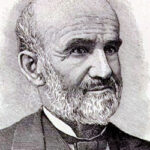

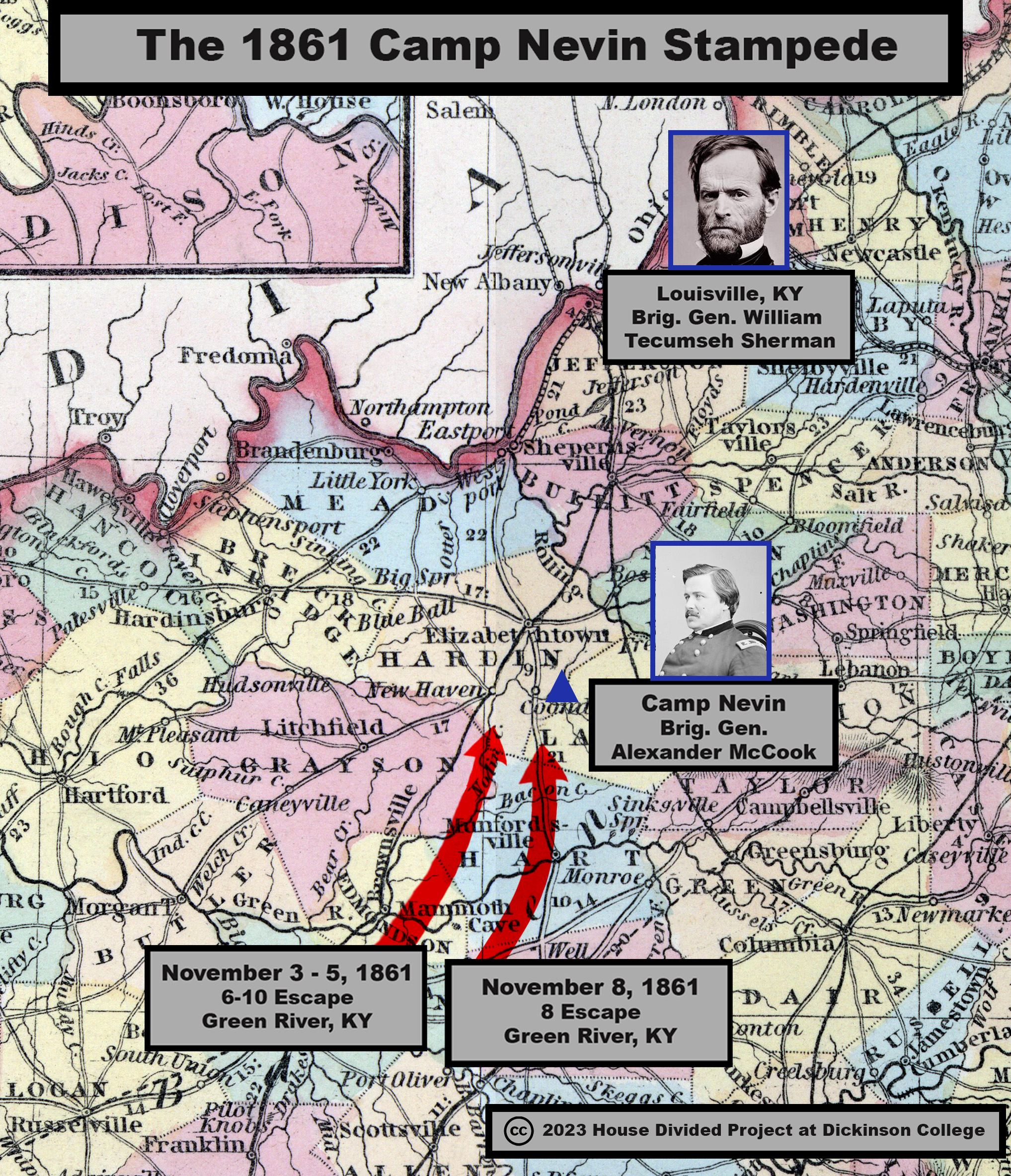

DATELINE: NOVEMBER 5, 1861, CAMP NEVIN, TEN MILES SOUTH OF ELIZABETHTOWN, KY

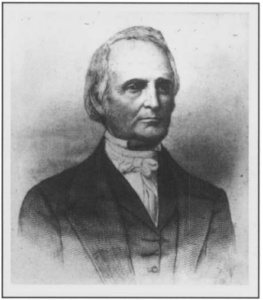

US general Alexander McDowell McCook hardly knew what to do about the enslaved people making a beeline for his camp from all over central Kentucky. Freedom seekers had been “a source of annoyance” to the general ever since he pitched camp along the banks of the Nolin River some 10 miles south of Elizabethtown, but the number and frequency of escapes seemed to be increasing daily. “Ten have come into my Camp within as many hours,” McCook reported on November 5, “and from what they say, there will be a general Stampeed of slaves from the other side of Green River.” Enslaved Kentuckians had been emboldened to run to US army lines by news of the federal government’s various new antislavery policies. But McCook’s primary concern remained keeping Kentucky in the Union, and for the time being that meant conciliating slaveholders. Instead of receiving the freedom seekers per War Department policy, McCook proposed “to send for their master’s and diliver [sic] the negro’s to them on the out-side of our lines.” [1] Group escapes forced otherwise reluctant US generals like McCook to take action and address slavery, though not always the type of action enslaved people wanted. In the critical border state of Kentucky, the official response of US military and civil authorities throughout the fall of 1861 continued to tilt in favor of conciliating slaveholders.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

In an internal report to his superior officer on November 5, US general Alexander McCook described the growing pattern of group escapes and expressed concern that his camp would soon be overrun by “a general Stampeed of slaves.” [2] Contemporary newspapers described the series of escapes to Camp Nevin, but so far no articles have been identified which refer to the escapes as a stampede.

MAIN NARRATIVE

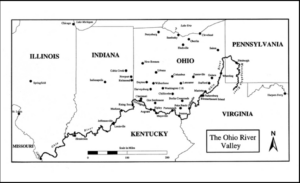

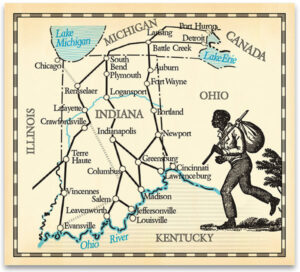

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the slave state of Kentucky officially remained neutral. But after Confederate forces disregarded neutrality and entered the state in September, US forces responded by moving into position in northern and central Kentucky.

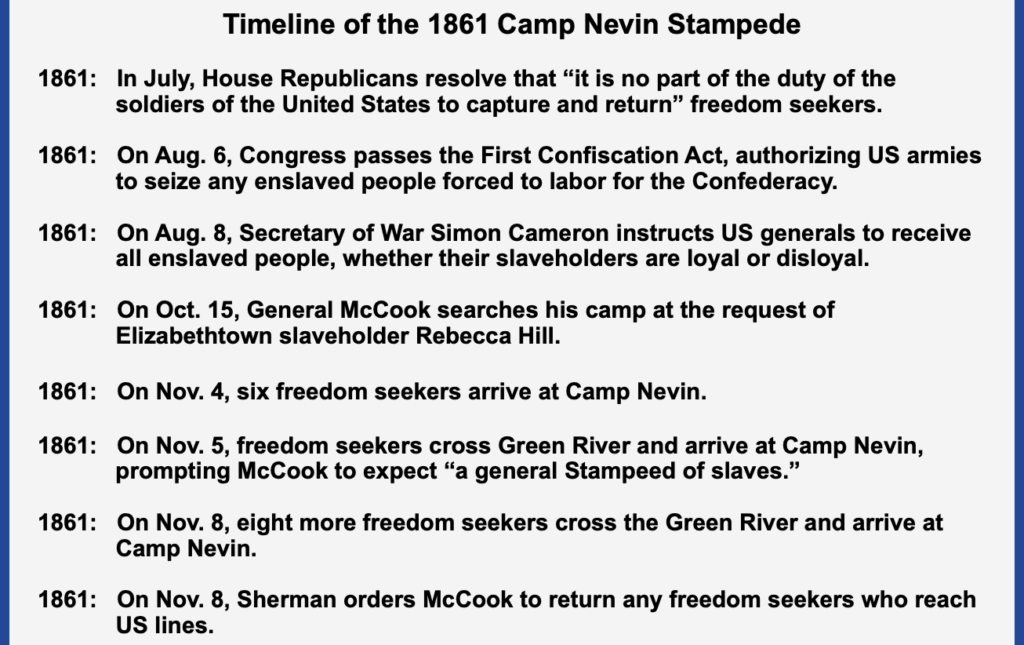

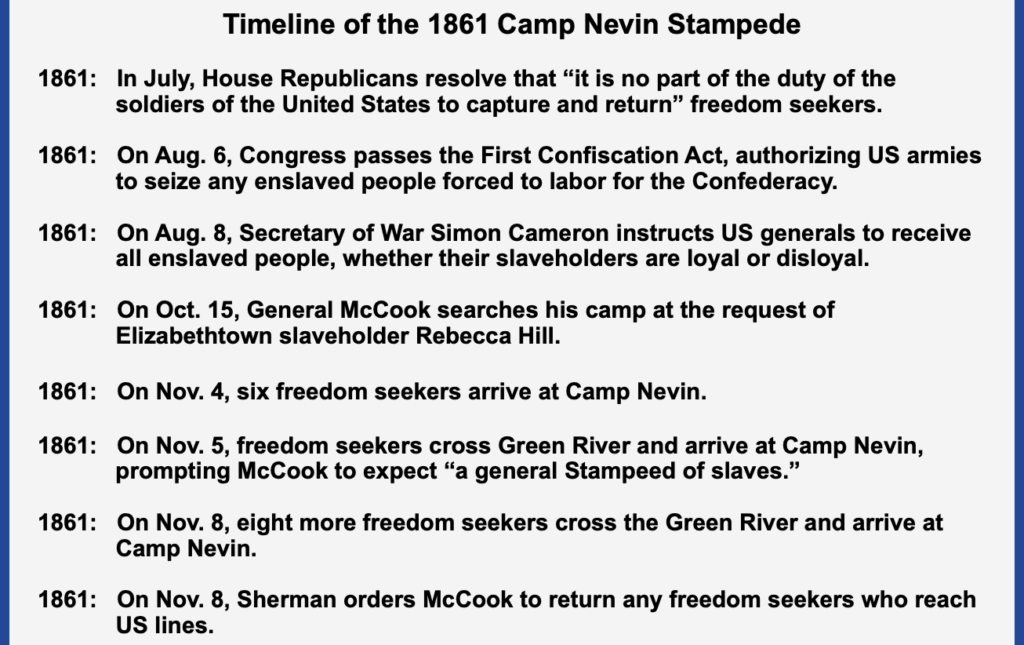

As soon as US forces entered the state, enslaved Kentuckians wasted little time running to US lines, encouraged by the federal government’s new antislavery policies. In May, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler declared enslaved people who ran to his lines at Fort Monroe, Virginia to be “contraband of war,” and refused to return them to their Confederate slaveholders. The contraband decision applied to enslaved people fleeing Confederate territory, but lawmakers in Washington soon expanded the scope of federal antislavery policies to include the border states as well. On July 9, House Republicans affirmed in a non-binding resolution that “it is no part of the duty of the soldiers of the United States to capture and return fugitive slaves.” [3] Less than a month later, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act. The law did not explicitly free anyone, but authorized US armies to seize any enslaved people forced by their slaveholders to labor for the Confederacy. It remained less clear how to distinguish which enslaved people had been forced to labor for the Confederacy. On August 8, Secretary of War Simon Cameron instructed US generals to receive all enslaved people, regardless of whether their enslavers were loyal or disloyal, while promising that the federal government would eventually compensate loyal slaveholders. [4]

But most US generals remained concerned that Kentucky might still secede and took pains not to alienate slaveholders in the state, even if that meant flouting federal antislavery policies. “It is absolutely necessary that we shall hold all the State of Kentucky,” insisted the US Army’s new general-in-chief, George B. McClellan, in early November, and “that the majority of its inhabitants shall be warmly in favor of our cause.” To that end, McClellan issued strict orders forbidding US generals from interfering with Kentucky’s “domestic institutions,” a familiar euphemism for slavery. [5]

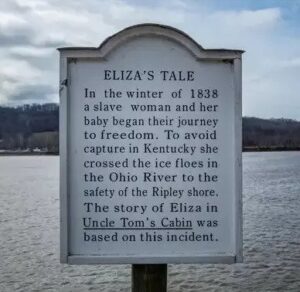

Even before McClellan’s instructions, most US generals in Kentucky were already taking care not to interfere with slavery. From his headquarters in Louisville, Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman repeatedly returned freedom seekers who reached his lines throughout October. When an enslaved man escaped from neighboring Spencer County into Sherman’s camp, Sherman saw that the man was turned over to local authorities in Louisville. [6] Several days later, two slaveholders complained to Sherman that soldiers belonging to the 19th Illinois Infantry were sheltering freedom seekers in their camp. Sherman promptly reprimanded the regiment’s commander, Col. John B. Turchin. “My orders are that all negroes shall be delivered up on claim of the owner or agent,” Sherman reiterated. As far as Sherman was concerned, “the laws of the state of Kentucky are in full force,” which meant that “negroes must be surrendered on application of their masters or agents or delivered over to the sheriff of the County.” [7]

Civil authorities at the federal, state, and local levels agreed with Sherman that the federal government’s antislavery policies did not change anything for slaveholders in a loyal state like Kentucky. State and local slave codes remained in force, as did the federal 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. When an enslaved man escaped from Louisville and crossed the Ohio River into southern Indiana, slaveholder E.L. Huffman turned to federal civil authorities in Indiana to recapture and return the freedom seeker under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. On Friday, October 11, the U.S. marshal for Indiana, D.G. Rose, captured the freedom seeker. U.S. Commissioner Reginald H. Hall, a Democrat from southern Indiana, held a brief rendition hearing and promptly remanded the man to slavery under the federal law. Louisville newspapers praised the federal civil officials who had “faithfully and fearlessly execute[d] the laws of the United States” and “defend[ed] the rights of Kentucky.” [8] In the meantime, state authorities worked to limit the war’s destabilizing impacts on slavery by discouraging US soldiers from assisting freedom seekers. The Kentucky state assembly in session at Frankfort weighed a proposal to punish any US military personnel “who shall aid, assist, encourage, or attempt to authorize a slave to escape” with a minimum one-year sentence in the state penitentiary. [9]

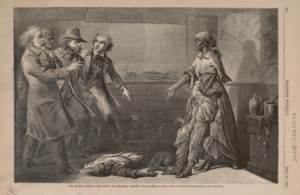

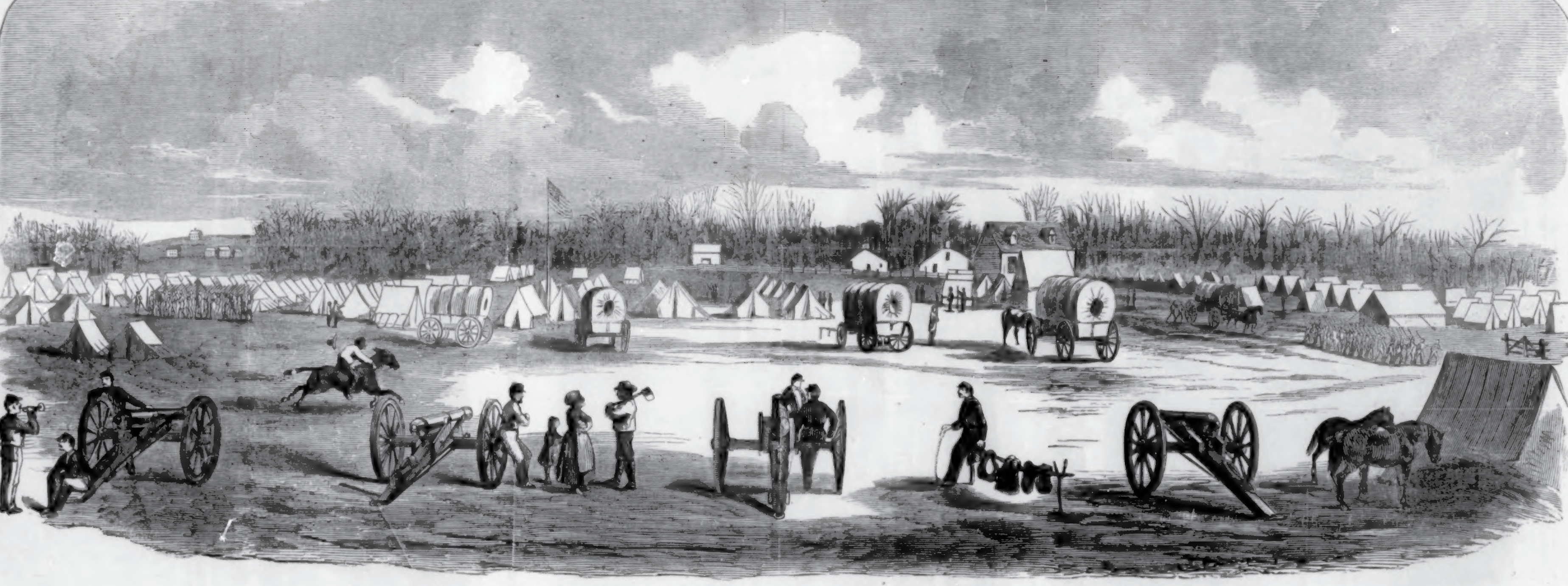

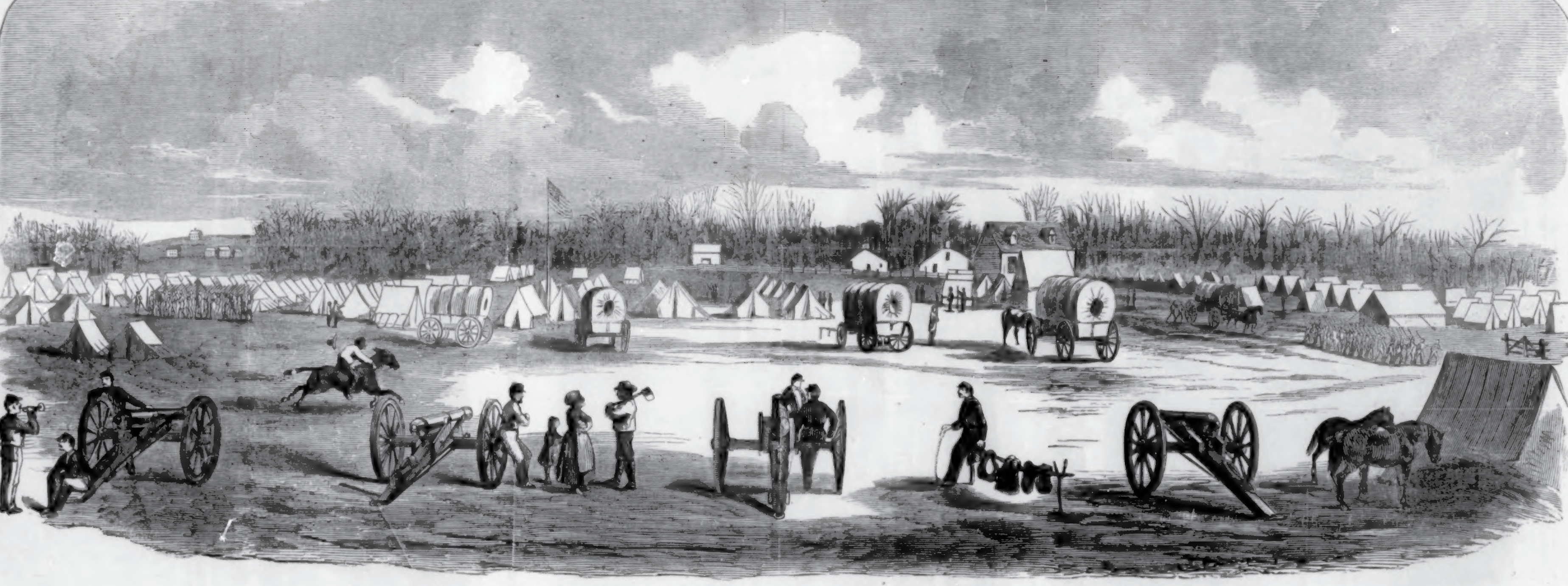

An artist for Harper’s Weekly depicted General McCook’s headquarters at Camp Nevin, located about 10 miles south of Elizabethtown, Kentucky. (House Divided Project)

From his advanced position at Camp Nevin, US general Alexander McCook followed the lead of Sherman and civil authorities by assisting slaveholders seeking to recapture freedom seekers. When slaveholder Rebecca Hill from nearby Elizabethtown showed up at McCook’s headquarters on October 15 grumbling that his soldiers were harboring an enslaved man, McCook promptly ordered his camp provost marshal, Capt. Orris Blake of the 39th Indiana Infantry, to “make diligent search for a negro boy.” [10] Had the number of freedom seekers remained relatively low and infrequent, McCook might have continued to placate disgruntled slaveholders who one-by-one appeared at his camp by simply ordering the provost marshal to conduct a sweep of the camp.

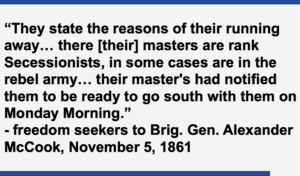

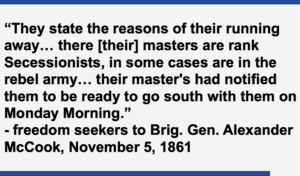

But enslaved Kentuckians had other ideas and kept running to Camp Nevin in mounting numbers throughout late October and early November 1861, carefully couching their statements to US officials in the language of the First Confiscation Act. Well aware that the recently passed law authorized US armies to seize enslaved people forced to labor for the Confederacy, freedom seekers repeatedly told US officials that their slaveholders had joined the Confederate army and forced them to transport supplies to Confederate troops or otherwise aid enemy forces. On November 4, McCook reported the arrival of six freedom seekers who informed him that their “masters have run away and joined the southern army.” [11] By the time McCook sat down to write a follow-up report to Sherman the next day, the number of freedom seekers had swelled to 10. This group had crossed the Green River on Sunday night, November 3 and covered some 50 miles to reach Camp Nevin by Tuesday, November 5. “They state the reasons of their running away,” McCook recorded, “there [their] masters are rank Secessionists, in some cases are in the rebel army,” and that “their master’s [sic] had notified them to be ready to go south with them on Monday Morning [November 4].” The freedom seekers also told McCook that many more enslaved people were preparing to escape, prompting the exasperated US general to predict that “there will be a general Stampeed of slaves from the other side of the Green River.” [12] That prophecy seemed to be fulfilled on Thursday, November 8, when another “batch of eight slaves” arrived at Camp Nevin, having escaped “from the Green River country or beyond.” At least “one or two” of those eight freedom seekers had previously escaped to Camp Nevin, only to be returned to slavery. For the time being, McCook turned all the freedom seekers over to Provost Marshal Blake, “who is as yet sorely puzzled to know what to do with them,” according to a report in the Louisville Courier. [13]

But enslaved Kentuckians had other ideas and kept running to Camp Nevin in mounting numbers throughout late October and early November 1861, carefully couching their statements to US officials in the language of the First Confiscation Act. Well aware that the recently passed law authorized US armies to seize enslaved people forced to labor for the Confederacy, freedom seekers repeatedly told US officials that their slaveholders had joined the Confederate army and forced them to transport supplies to Confederate troops or otherwise aid enemy forces. On November 4, McCook reported the arrival of six freedom seekers who informed him that their “masters have run away and joined the southern army.” [11] By the time McCook sat down to write a follow-up report to Sherman the next day, the number of freedom seekers had swelled to 10. This group had crossed the Green River on Sunday night, November 3 and covered some 50 miles to reach Camp Nevin by Tuesday, November 5. “They state the reasons of their running away,” McCook recorded, “there [their] masters are rank Secessionists, in some cases are in the rebel army,” and that “their master’s [sic] had notified them to be ready to go south with them on Monday Morning [November 4].” The freedom seekers also told McCook that many more enslaved people were preparing to escape, prompting the exasperated US general to predict that “there will be a general Stampeed of slaves from the other side of the Green River.” [12] That prophecy seemed to be fulfilled on Thursday, November 8, when another “batch of eight slaves” arrived at Camp Nevin, having escaped “from the Green River country or beyond.” At least “one or two” of those eight freedom seekers had previously escaped to Camp Nevin, only to be returned to slavery. For the time being, McCook turned all the freedom seekers over to Provost Marshal Blake, “who is as yet sorely puzzled to know what to do with them,” according to a report in the Louisville Courier. [13]  The growing trend of group escapes presented a problem for McCook, not because he secretly sympathized with slaveholders, but because the large number of freedom seekers within his camp seemed to confirm white Kentuckians’ suspicions that the US army intended to interfere with slavery. “The subject of Contraband negros is one that is looked to, by the Citizens of Kentucky of vital importance,” McCook began his November 5 report to Sherman. If the freedom seekers “be allowed to remain here,” McCook worried, “our cause in Kentucky may be injured.” Pro-secessionist Kentuckians “bolster themselves up, by making the uninformed believe that this is a war upon African slavery.” McCook had “no great desire to protect [Kentucky’s] pet institution Slavery” and made clear that he was “very far from wishing these recreant masters in possession of any of their property.” But keeping Kentucky in the Union took precedence over all else. To assure white Kentuckians that the US army’s presence did not portend general emancipation, McCook proposed “to send for their master’s and diliver the negro’s [sic] to them on the out-side of our lines.” [14]

The growing trend of group escapes presented a problem for McCook, not because he secretly sympathized with slaveholders, but because the large number of freedom seekers within his camp seemed to confirm white Kentuckians’ suspicions that the US army intended to interfere with slavery. “The subject of Contraband negros is one that is looked to, by the Citizens of Kentucky of vital importance,” McCook began his November 5 report to Sherman. If the freedom seekers “be allowed to remain here,” McCook worried, “our cause in Kentucky may be injured.” Pro-secessionist Kentuckians “bolster themselves up, by making the uninformed believe that this is a war upon African slavery.” McCook had “no great desire to protect [Kentucky’s] pet institution Slavery” and made clear that he was “very far from wishing these recreant masters in possession of any of their property.” But keeping Kentucky in the Union took precedence over all else. To assure white Kentuckians that the US army’s presence did not portend general emancipation, McCook proposed “to send for their master’s and diliver the negro’s [sic] to them on the out-side of our lines.” [14]

AFTERMATH

General Sherman agreed that the US military’s interests lay in conciliating Kentucky slaveholders. On November 8, Sherman ordered McCook to return the freedom seekers. “We have nothing to do with them [enslaved people] at all and you should not let them take refuge in Camp,” Sherman advised. “It forms a source of misrepresentation by which Union men are estranged from our Cause.” [15] The ultimate fate of the freedom seekers remains unclear. Although Sherman clearly directed McCook to return them, no record survives. Some of the freedom seekers may have eluded recapture with help from free Black servants working for the US army or enlisted men sympathetic to their plight.

For his part, General McCook seemed willing to return freedom seekers well into the spring of 1862, even after US forces had made inroads into the Confederate state of Tennessee. A Nashville, Tennessee paper praised McCook’s “courteous and gentlemanly” treatment of slaveholders, which “acquit the Federal army and its officers of conniving at the escape of slaves.” Antislavery papers did not see it that way and attacked General McCook for his conciliatory approach to slaveholders. The Liberator reprinted the Nashville paper’s glowing report on McCook under the damning headline, “How General McCook Conciliates the Rebels.” Massachusetts senator Henry Wilson read the Liberator’s searing critique on the Senate floor in May while concluding that McCook was among the “generals at the West who think they do their duty best when they serve slavery.” [16]

FURTHER READING

The correspondence between McCook and Sherman is reprinted in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation. [17] Although McCook biographer Wayne Faneburst discusses the group escapes to Camp Nevin and the negative reputation McCook gained among antislavery circles for his willingness to return freedom seekers, few scholars of wartime emancipation have taken notice of the stampede. [18]

NOTES

[1] Alexander McDowell McCook to William Tecumseh Sherman, November 5, 1861, Camp Nevin, Ky., RG 393, pt. 1, entry 3534, box 1, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, excerpted in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520.

[2] McCook to Sherman, November 5, 1861, RG 393, pt. 1, entry 3534, box 1, NARA, excerpted in Freedom, ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520.

[3] Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 1st Sess., 32; James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 112-113.

[4] Oakes, Freedom National, 122-139.

[5] George B. McClellan to Don Carlos Buell, November 7, 1861, Washington, DC, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), ser. 2, vol. 1, 776-777.

[6] Louisville, KY Courier, October 12, 1861, p3, c2.

[7] William T. Sherman to John B. Turchin, October 15, 1861, Louisville, Ky., OR, ser. 2, vol. 1, p. 774; Sherman to McCook, November 8, 1861, Louisville, Ky., excerpted in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520.

[8] “Fugitive Slave Returned from Indiana,” Louisville, KY Courier, October 15, 1861, p2, c3; “Fugitive Slave Returned,” Louisville, KY Daily Democrat, October 15, 1861, p2, c1.

[9] “Kentucky Legislature,” Louisville, KY Courier, September 30, 1861, p3, c3.

[10] Special Order No. 4, October 15, 1861, Camp Nevin, Ky., RG 393, pt. 2, entry 6465, vol. 149/246DO, NARA.

[11] McCook to Sherman, November 4, 1861, quoted in Wayne Fanebust, Major General Alexander M. McCook, USA: A Civil War Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 70.

[12] McCook to Sherman, November 5, 1861, RG 393, pt. 1, entry 3534, box 1, NARA, excerpted in Freedom, ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520.

[13] “Contrabands,” Louisville, KY Courier, November 12, 1861, p3, c1.

[14] McCook to Sherman, November 5, 1861, RG 393, pt. 1, entry 3534, box 1, NARA, excerpted in Freedom, ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520.

[15] Sherman to McCook, November 8, 1861, Louisville, Ky., excerpted in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520.

[16] “How General McCook Conciliates the Rebels,” Boston Liberator, April 11, 1862, p3, c2; Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd Sess., 1893. For other allegations that McCook was overly sympathetic to slaveholders (some of which were made by his political enemies), see Faneburst, Major General Alexander M. McCook, 70-71.

[17] McCook to Sherman, November 5, 1861, RG 393, pt. 1, entry 3534, box 1, NARA, excerpted in Freedom, ser. 1, vol. 1, 519-520; Sherman to McCook, November 8, 1861, Louisville, Ky., also excerpted in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation ser. 1, vol. 1, pp. 519-520. McCook’s letter and Sherman’s response are also reprinted in OR, ser. 2, vol. 1, 776-777.

[18] Faneburst, Major General Alexander M. McCook, 70-71.