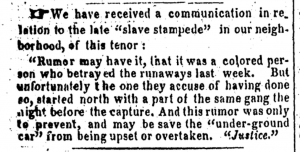

1853 || From Freemen’s Manual: A Campaign Serial of the Independent Democracy (Vol 1, Columbus, OH: 1853):

“NEGRO STAMPEDE. Slaves are running away from Missouri, at the present time, in battalions. Three belonging to Mr. R. Meek, of Weston, ran away on Wednesday of last week—two of whom were afterwards apprehended. They were making for the Plains. Fifteen made a stampede from Ray county, the week before, and took the line of their march for Iowa. Several were captured in Grundy county, but the larger number made good their escape. It would be a glorious thing for Missouri, if all her slaves should take it into their heads to run away. If she only knew it, they are one of the greatest drawbacks to her advancement and prosperity. —Alton Telegraph.” (p. 39)

“THE KIDNAPPING CLAUSE (from the New York Tribune)….Here, then, is one salient point—at the date of the Constitution there were two distinct classes of persons who might flee from servitude and be recovered; and that which was most likely to require some provision for recapture was the class that could and did owe service, though its servitude was popularly termed “involuntary.” Negroes had not then reached the point of general stampede; their fugacity gave very little trouble; but the bound servants were in the very act of a general escape. They were utterly restless.” (p. 107)

“SLAVE STAMPEDE. The Cincinnati Commercial says there was a serious negro stampede from plantations sixty miles back of the river, in Kentucky, on Saturday night. Of eleven slaves who decamped, five succeeded in crossing the Ohio, a few miles below this city, yesterday. *Their pursuers were in town last night, but learning that the fugitives had got twelve hours start, soon gave up the chase.” (p. 141)

“UNDERGROUND RAILROAD. We learn from the Fact that “still another slave stampede came off a few miles below Maysville on Wednesday night last. Five negroes—three of them very fair and delicate mulatto girls—succeeded in crossing the river.— All trace was lost a few miles back of Ripley, Brown county.” (p. 153)

1854 || From The Friend: A Religious and Literary Journal (Philadelphia, 1853):

“Slave Stampede.—The slaves in Mason county, Va., are becoming migratory in their habits. Within the last fortnight eight have made their escape to parts unknown.”—Ledger. (p. 63)

1856 || From Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States; with Remarks on Their Economy (London, 1856)

“Under this ‘Organization of Labor,’ most of the slaves work rapidly and well. In nearly all ordinary work, custom has settled the extent of the task, and it is difficult to increase it. The driver who marks it out, has to remain on the ground until it is finished, and has no interest in over-measuring it; and if it should be systematically increased very much, there is danger of a general stampede to the ‘swamp’–a danger the slave can always hold before his master’s cupidity.” (pp. 435-6)

1858 || From Salmon P. Chase Papers, Vol. 3 (edited by John Niven):

“EDITORIAL NOTE: Chase refers to a letter supposedly written in May 1858 by Col. Hugh Forbes (b. ca. 1813), a Scotch specialist in guerrilla warfare who had served with Garibaldi and with free- state forces in Kansas. According to the New York Herald, Forbes had organized a “stampede” of slaves from the border states. Included in the letter, which Forbes supposedly sent to several prominent antislavery leaders, was a notation that “Copies will be sent to Governor Chase, who found money, and Governor Fletcher, who contributed arms, and to others interested.” Cincinnati Gazette, Oct. 28, 1859; New York Herald, Oct. 27, 1859″ (3: 23n)

1859 || From New York Independent, Dec. 8, 1859 (quoted in The Independent, Vol. 74, 1913):

“John Brown failed in his scheme of a general slave stampede (he never planned an insurrection or a revolution) because in the very nature of the case this was impracticable. The slaves were not prepared for it, nor was there any feasible mode of accomplishing it. Such a movement, always doubtful and hazardous when the slaves themselves are enlisted in it, must, of course, be futile when they are not ripe for it; and to put in jeopardy the safety and the lives of a whole community in an unsolicited and necessarily hopeless attempt to benefit any portion of it, is a measure that cannot be justified by any code of ethics, natural or Christian.” (p. 126)

1859 || From Martin Delany, Blake, Or the Huts of America (1859):

“The absence of Mammy Judy, Daddy Joe, Charles, and little Tony, on the return early Monday morning of Colonel Franks and lady from the country, unmistakably proved the escape of their slaves, and the further proof of the exit of ‘squire Potter’s Andy and Beckwith’s Clara, with the remembrance of the stampede a few months previously, required no further confirmation of the fact, when the neighborhood again was excited to ferment.” (opening paragraph of Chapter 30, “The Pursuit,” p. 139)

1860 || From John Kagi, interviewed by Richard J. Hinton in James Redpath, The Public Life of Capt. John Brown (1860):

“It was not anticipated that the first movement would have any other appearance to the masters than a slave stampede, or local insurrection, at most. The planters would pursue their chattels and be defeated.” (p. 204)

At Washington City the military force was increased, and every precaution taken to keep the negroes down. A telegraphic despatch from the Capital, on the 18th — the day when John Brown was captured — thus portrays their fears and the reason for them: “It appears from intelligence received here to-day from various portions of Virginia and Maryland, that a general stampede of slaves has taken place. There must have been an understanding of some nature among them in reference to this affair, for the numerous instances — so I am Informed by the slave holders since this insurrection — they have found it almost impossible to control them.” (p. 267)

1861 || From South Carolina correspondent (NY Daily Tribune, March 19, 1861), quoted in Herbert Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts (6th ed., 1993):

“There has recently been a stampede of about 100 slaves from the interior of this State, about which but little is said, and of which, I dare say, you will see nothing in the local papers. The demoralization consequent on the political disorders of the day has extended to the slave population. There is a manifest uneasiness in this respect.”

1861 || From Debates over North Carolina Secession quoted in Samuel A’Courte Ashe, History of North Carolina: From 1783 to 1925 (Vol. 2, 1925):

It was estimated that some 15,000 troops would be needed for State defense, and that the cost would be over six and a half million dollars for the first year. This information challenged the thoughtful attention of the Convention and startled the delegates as to the expense of war. The necessity of protecting the coast was, however, apparent, and that subject early received earnest consideration. Day after day it was considered in secret session. “Indignation was expressed at the movement of troops by the Confederate Government. There was apprehension that there would be a stampede of slaves to the Federal army as soon as it appeared on the coast: but after much debate it was resolved that four regiments should be raised from the eastern counties to protect that region.” (p. 625)

1861 || From Edward Everett, “Questions of the Day,” July 4, 1861 reprinted in Orations and Speeches on Various Occasions (Vol. 2):

“How can peace exist when all the causes of dissension shall be indefinitely multiplied; when unequal revenue laws shall have led to a gigantic system of smuggling; when a general stampede of slaves shall take place along the border, with no thought of rendition, and all the thousand causes of mutual irritation shall be called into action, on a frontier of 1,500 miles not marked by natural boundaries and not subject to a common jurisdiction or a mediating power?” (p. 397)

1861 || From Gen. Alexander McCook (Nov. 5, 1861) reprinted in OR, Series 1, Vol. IV):

“The subject of contraband negroes is one that is looked to by the citizens of Kentucky of vital importance. Ten have come into my camp within as many hours, and from what they say there will be a general stampede of slaves from the other side of Green River. They have already become a source of annoyance to me, and I have great reason to believe that this annoyance will increase the longer we stay. They state the reasons of their running away their masters are rank secessionists, in some cases are in the rebel army, and that slaves of Union men are pressed into service to drive teams, &c.” (p. 337)

1876 || From Thomas Wentworth Higginson quoted in Memoir of Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe (1876)

“The next anti-slavery milestone was when, in 1858, John Brown came eastward. A keen thinker has said, that every path on earth may lead to the dwelling of a hero; and of course the track was plain enough between John Brown’s door and that of Dr. Howe. Few, if any, knew Capt. Brown’s plans in full detail; but the project of a slave stampede on a large scale was quite in Dr. Howe’s line, and he, with others, entered into it cordially.” (p. 121)

1877 || From John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms (4th ed. 1877):

“STAMPEDE. (Span, estampado, a stamping of feet.) A general scamper of animals on the Western prairies, usually caused by a fright. Mr. Kendall gives the following interesting account of one …From animals, the term is transferred to men: —The boys leaped and whooped, flung their hats in the air, chased one another in a sort of stampede, &c. — Judd’s Margaret, p. 120.

After him I went, and after me they came, and perhaps there wasn’t the awfullest stampede down three pair of stairs that ever occurred in Michigan! — Field, Western Tales.

The cause that led to the recent alarm [in Paris] was the stampede among the directors of that wonderful institution, the Credit Mobilier.—N. Y. Journal of Commerce. Oct. 12, 1857.

From information which has reached us, there would seem to have been a considerable stampede of slaves from the border valley counties of Virginia during the late Easter holidays. — (Balt.) Sun, April 9, 1858.” (pp. 652-3)

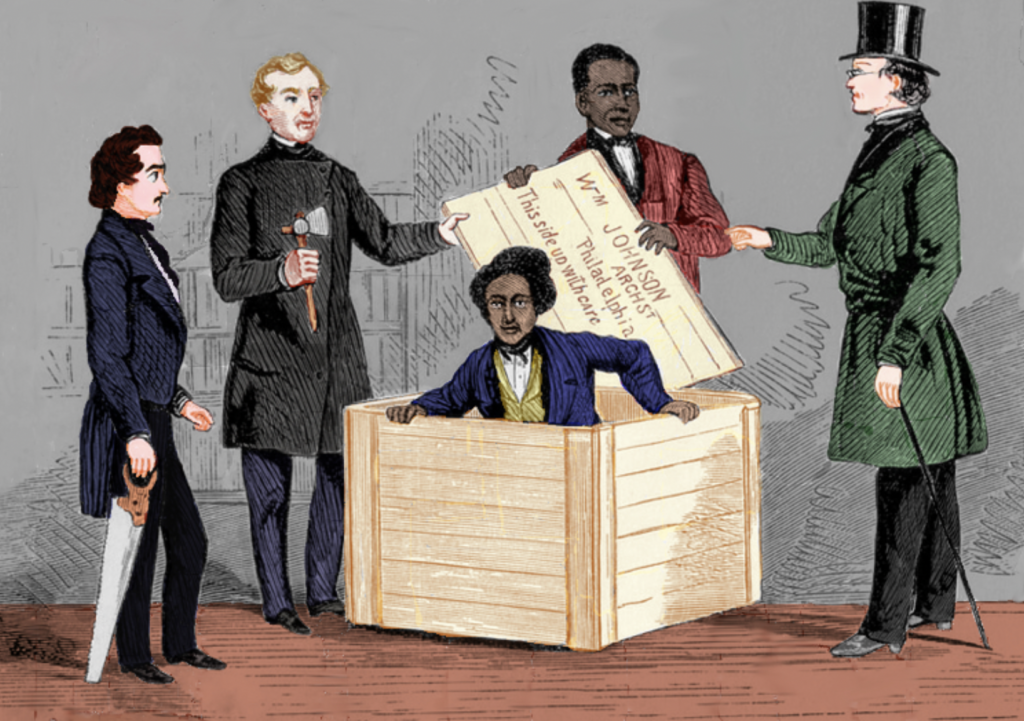

1892 || From Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892)

“In all my forty years of thought and labor to promote the freedom and welfare of my race, I never found myself more widely and painfully at variance with leading colored men of the country than when I opposed the effort to set in motion a wholesale exodus of colored people of the South to the northern states [during Reconstruction]; and yet I never took a position in which I felt myself better fortified by reason and necessity….Thousands of these poor people, traveling only so far as they had money to bear their expenses, were dropped in the extremest destitution on the levees of St. Louis, and their tales of woe were such as to move a heart much less sensitive to human suffering than mine. But while I felt for these poor deluded people, and did what I could to put a stop to their ill-advised and ill-arranged stampede, I also did what I could to assist such of them as were within my reach, who were on their way to this land of promise.” (p. 524)

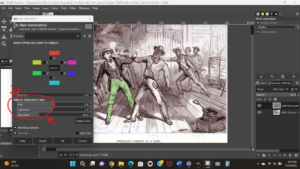

(4a. To access “Tool Options” (if it does not pop up automatically when you begin to use the Paintbrush), click on “Windows” in the menu bar at the top of the page. Hover your mouse over “Dockable Dialogues”, and you should see “Tool Options” at the top of the drop-down menu that appears. Click “Tool Options”. A window in which you can adjust opacity levels, brush size, and other metrics as you please should open.)

(4a. To access “Tool Options” (if it does not pop up automatically when you begin to use the Paintbrush), click on “Windows” in the menu bar at the top of the page. Hover your mouse over “Dockable Dialogues”, and you should see “Tool Options” at the top of the drop-down menu that appears. Click “Tool Options”. A window in which you can adjust opacity levels, brush size, and other metrics as you please should open.)

On Friday evening, January 9, 1863, Abraham Lincoln held a private meeting at the White House with two key Republican senators –

On Friday evening, January 9, 1863, Abraham Lincoln held a private meeting at the White House with two key Republican senators –