According to historian Nikki Taylor, “African American women are at the heart of American history and its many subfields.”[1] This statement certainly captures the essence of Taylor’s argument in Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio, which describes the life of Margaret Garner and the sad fate of her enslaved family. Their experiences are used to analyze the pain that African American women endured in the antebellum period. Like many enslaved women, Garner had endured unthinkable traumas on the plantation she was bound to in Richwood, Kentucky. In addition to the forced labor she completed, she was also subject to verbal, physical, and sexual abuse in many forms.[2] According to Taylor, the tragic events that occurred following the Garners’ escape from slavery likely stemmed from this trauma.

Taylor does not discuss the term “stampede” as a form of slave escapes in her book. She does, however, acknowledge the obstacles and potential successes of slave escapes in general. Taylor explains that the most likely demographic to make it to freedom were younger men who traveled alone. Yet the Garner family traveled as a group of eight, with the youngest member at nine months old and the eldest in their fifties.[3] Margaret Garner’s husband, Simon Jr. (later named Robert), had the most geographic experience of the group because his slaveholder had granted him jobs away from the plantation.[4] According to Taylor, enslaved people in Kentucky were unlikely to escape relative to other areas due to the close ratio of white slaveholders to enslaved people. In Kentucky, it was more likely for enslaved people to engage in acts of resistance rather than attempt escape.[5]

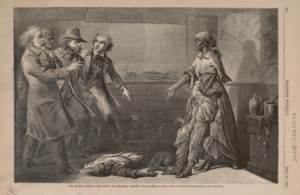

“The Modern Medea” (1867), Painting of Margaret Garner’s Actions by Thomas Satterwhite Noble (Library of Congress)

The Garners were set on freedom, however, despite the grim circumstances. They deliberated for over a month to determine their route to Ohio, which was just sixteen miles away.[6] They left the plantation at 10:00 pm on January 27, 1856, with a sled pulled by two horses. They had to cross the frozen—yet still dangerous—Ohio River, but their escape was successful. The family arrived in the free territory of Cincinnati, Ohio at 8:00 am on January 28.[7] Their relief was short-lived, however. Slaveholders quickly noticed the Garners were missing and began their pursuit. Once in Ohio, Archibald Gaines and Thomas Marshall obtained a warrant under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act to repossess the Garners as their property. When a deputized group of people arrived at the home where the Garners were staying, they decided to fight rather than return to slavery. Robert shot a deputy and tensions escalated.[8] Assuming they would not make it out, Margaret grabbed a knife and slit the throat of her two-year-old daughter. She wanted her children to die rather than remain enslaved. She attempted to kill the rest of her children, but she was stopped by the owners of the house. Later, in an interview with Reverend Horace Bushnell, Garner claimed it was better for her children “to go home to God than back to slavery.”[9] The deputies forced their way through the door to take the pistol away from Robert. In a final attempt to prevent the enslavement of her children, Margaret hit her nine-month-old daughter in the face with a shovel.[10]

The Garners’ fugitive slave trial transfixed people in Cincinnati. Crowds of Black and White anti-slavery protestors came to the courthouse each day. Groups of women also came to protest the separate murder trial involving Margaret Garner. This was significant because, according to Taylor, they were “the first documented collective and public protests by Black women on behalf of another Black woman in US history.”[11] On February 26, 1856, the court decided the Garners would be returned to their owners. In Kentucky, and an arrest warrant was issued for the Garner parents concerning their daughter’s murder. To prevent their arrest by Ohio officials, the slaveholders and their allies had the Garners sent on a steamboat to New Orleans. Yet on this journey, the boat collided with another, and Margaret’s youngest daughter was thrown from her hands into the water. Margaret appeared to be relieved that her daughter was finally free from slavery.[12]

Taylor uses the psychological concept of “soul murder” to place “physical, sexual, and mental trauma, abuse, and torture” alongside Margaret Garner’s story.[13] Overall, her book aims to utilize the trauma endured by Margaret and her family as a lens through which to analyze a mother’s murderous actions. Taylor writes that “there is a direct relationship between racist and sexist insults, sexual and physical assaults—injustice in any form—and psychological pain.”[14] Her literature seeks to make this relationship clear to her readers and give Margaret the voice she deserves. Previously, her story had been regarded as “non-narratable” by many historians and scholars, but Taylor’s work seeks to unravel the “black feminist interpretation” of Margaret’s choices.[15] According to Taylor, the spiral of psychological torture throughout Margaret’s life could only end with her tragic attempts to end her children’s enslavement.

[1] Nikki M. Taylor, Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2016), 6.

[2] Taylor, 27.

[3] Taylor, 8.

[4] Taylor, 9-10.

[5] Taylor, 10-11.

[6] Taylor, 12.

[7] Taylor, 15-17.

[8] Taylor, 20.

[9] Taylor, 74.

[10] Taylor, 21-22.

[11] Taylor, 66.

[12] Taylor, 84-87.

[13] Taylor, 3.

[14] Taylor, 3.

[15] Taylor, 5.