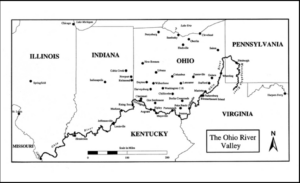

Cincinnati and Ripley, both on the Ohio River, proved to be strong anti-slavery outposts to help enslaved people escape to the North (Front Line of Freedom)

While living in Cincinnati, John Malvin, a formerly enslaved man from Kentucky, became an Underground Railroad operative. While staying in Ohio sometime between 1827 and 1831, he helped a woman by the name of Susan Hall escape. Malvin devised a plan to free her and her two daughters from a steamship on the Ohio River. Motivated by his “abhorrence of slavery,” he snuck onto the steamship and led away Hall, her daughter and three others.[1] He tricked the armed guards on the ship and stole away Hall, one of her daughters, and three other freedom seekers, eventually helping them reach Canada.

Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley by Keith P. Griffler tells the stories of Malvin and countless other African Americans from the Ohio River valley. In the book, Griffler only uses the term “stampede” once, from a Kentucky newspaper article describing large numbers of freedom seekers escaping from Northern Kentucky and flooding into African American communities in Ohio and elsewhere.[2] Griffler uses a variety of sources, including letters from Levi Coffin to various historical newspapers from around Cincinnati.

Cincinnati in 1848, seven years after a brutal clash between pro and anti-slavery forces in the city (Front Line of Freedom)

Griffler details multiple instances of African Americans defending their communities against pro-slavery vigilantes, such in the case of “Major” James Wilkerson (a nickname he was given by either anti-slavery allies). On Friday, September 3, 1841, a group of pro-slavery Kentuckians, angered by the growing African American community and by the lack of enforcement of the 1807 “Black Laws,” came to Cincinnati armed with guns and the intent to threaten the black community. Wilkerson, a formerly enslaved man whose grandfather fought at the Battle of Saratoga (1777) came out with others from the black community “armed with rifles and muskets.”[3] The Kentuckians forced them to retreat due to a “well-executed counterattack.” [4] After the violence of 1841, Cincinnati began arresting members of the African American community, where “the majority were either required to post bond, or were released upon providing a ‘certificate of nativity.’”[5]

Reverend John Rankin was a crucial part of Ripley, Ohio’s resistance to slavery (Front Line of Freedom)

Griffler also details other instances of violence. Ripley was also a hotspot of formerly enslaved African Americans who were constantly helping other freedom-seekers to escape during the 1840s. However, slave catchers were frequently surveying the area as well. One incident of a standoff occurred when Richard Rankin threatened a slave hunter with a “revolver to his head.”[6] In 1841, leading abolitionists Reverend John Rankin and Calvin Rankin fought off slave hunters.[7] Luckily, they forced the group into retreat, and continued to help enslaved people to freedom.

Front Line of Freedom ultimately highlights how multi-racial resistance to slavery was strong in places like Cincinnati or Ripley Ohio. Griffler details other notable resistance figures such as John Parker, J.C. Brown, Charles Langston, John Mason, and Frances Jane Scroggins.

Endnotes:

[1] 1. Keith P. Griffler, Front Line of Freedom African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley (The University Press of Kentucky, 2015), 39-40.

[2] Griffler, 119

[3] Griffler, 54

[4] Griffler, 54-55

[5] Griffler, 56

[6] Griffler, 83

[7] Griffler, 83