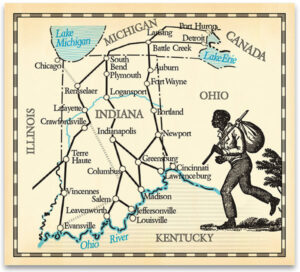

“While the lower North was uniquely southern and the upper South was uniquely northern,” writes Matthew Salafia in Slavery’s Borderland (2013), “the result was a region defined by its blend of influences.”[1] The author examines the importance of the Ohio River as a geographical, cultural, social, and political marker throughout the antebellum period and into the Civil War. Although opinions were strong and tensions were high between the North and the South in the years leading to the war, Salafia claims that the Ohio River Valley region remained committed to coexistence. Borderland residents rejected the sectionalism experienced throughout the rest of the country.[2]

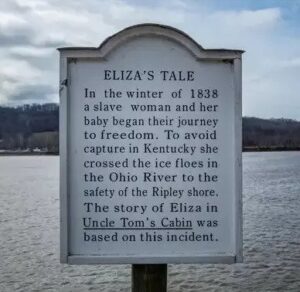

Of significance to this project, Salafia discusses the “role of location, power, and politics in the institution of slavery.”[3] He uses a historical lens to explore the differences and similarities between the wage labor and chattel slavery systems that existed simultaneously along the banks of the Ohio River. Salafia explains that between the sentiments of White abolitionists, Black abolitionists, and pro-slavery sentiments, a form of “conservative antislavery” ultimately prevailed.[4] Salafia specifically discusses the experiences of freedom seekers in his book, who had to cross “shared social boundaries between slavery and freedom.”[5] Escaped bondsmen and women often attempted to blend in with the free Black population in Ohio by shedding their identity as enslaved persons and adopting that of a wage laborer before relocating to further safety. Salafia also mentions that freedom seekers would weigh the benefits of escaping slavery against the possible limitations before attempting to flee. Those who decided not to flee likely realized that in practice, the “freedom” in the nearby borderland was often tainted by practices of forced labor that closely resembled the same system they were attempting to evade.[6]

Salafia does not use the term “stampede” in his book, but he does mention various family escape attempts. He explains that it was often difficult for enslaved individuals and their families to escape as a unit, and they only did so when they foresaw no possible alternatives. He emphasizes that “many slaves along the border escaped only after a triggering event threatened to tear them away from their community or forced them to reevaluate their enslaved condition.”[7] The borderland had additionally become more legally defined following the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.[8] T

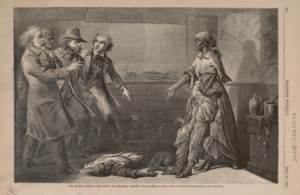

“The Modern Medea” (1867), Painting of Margaret Garner’s Actions by Thomas Noble (Library of Congress)

With specific reference to the limited number of group escapes, Salafia explains that the close bonds of family members often made their escape together difficult. “Group flight presented multiple challenges,” he writes, “making it more difficult for runaways to blend into the surroundings, find shelter, and gather food, but individual escape required fugitives to abandon their families to the yoke of bondage.”[9] Specifically, Salafia mentions George Ramsey, J.D. Green, Mary Younger, William Brown, John Moore, Henry Bibb, Charlotte, and Margaret Garner as enslaved people who had to make difficult decisions about escape and the future of their families.[10] These men and women had to consider the benefits, costs, and risks associated with escape before planning a course of action. If they were caught, some—such as Margaret Garner—were so distraught by the idea of being returned to slavery that they believed death was the better and necessary alternative.[11]

To help with slave escapes, several Black and white community members provided their homes, businesses, communication, money, and other services to men, women, and children seeking freedom. Prominent members who helped freedom seekers in free territories included Salmon P. Chase, a prominent abolitionist attorney and politician; Elijah Kite and his wife, who opened their home to Margaret Garner and her family; and the community of free African Americans in general, who provided “emotional, psychic, and sometimes physical support.”[12] Overall, Matthew Salafia uses the scope of his book to discuss the institution of slavery through the geographic consideration of the Ohio River Valley.

[1] Matthew Salafia, Slavery’s Borderland: Freedom and Bondage along the Ohio River (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 2.

[2] Salafia, 3.

[3] Salafia, 5.

[4] Salafia, 7.

[5] Salafia, 10.

[6] Salafia, 11.

[7] Salafia, 168.

[8] Salafia, 76-78.

[9] Salafia, 175.

[10] Salafia, 175-180.

[11] Salafia, 180.

[12] Salafia, 166 & 180.