In July of 1839, Virginia slave catchers caught a man named William “Black Bill” Mitchell in Marion, Ohio. Mitchell, who had escaped from Virginia, was living in Marion since the fall of 1838, where his various talents “quickly made him a valued member of the community.”[1] Mitchell was brought before the court, where it was eventually ruled that the slave catchers were in the wrong because they were bringing Mitchell back to the wrong slaveholder. Chaos broke out immediately after the ruling, as armed slave catchers grabbed Mitchell, “waving their weapons and threatening the lives of all who tried to stop them.”[2] Some local residents chased after them and fought the slave catchers off, allowing Mitchell to escape northward to Canada. In addition, the slave catchers “were found guilty of contempt of court,” and fined accordingly.[3]

The Reverse Underground Railroad in Ohio by David Meyers and Elise Meyers Walker describes the legal, political, social, and often physical conflict between pro and anti-slavery forces in Ohio and Kentucky. While Meyers and Walker make no reference to “slave stampedes,” they document numerous accounts of group escapes by freedom-seekers and other instances of local Ohio abolitionists bringing cases to court to sue for the freedom of enslaved people escaping through Ohio. They use newspapers and other primary sources to show how freedom seekers and abolitionists worked together to fight back against slavery.

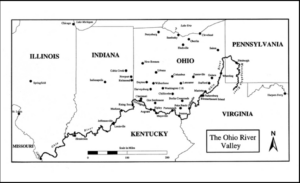

Meyers and Walker documented plenty of group escapes, like the trio of Henry, George, and Reuben, three enslaved musicians who made their escape to Canada. Throughout the late 1830s, the three were allowed by Kentucky slaveholder Dr. Jones Graham to travel with a free Black musician named Henry Williams to places like Louisville, New Orleans, and other southern cities along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The enslaved musicians routinely sent their earned money back to Graham.[4] During the winter of 1840-41, however, the three musicians saw an opportunity for freedom after meeting another enslaved man named Milton Clarke. Clarke told the trio about his plan to cross the Ohio River. [5] They crossed the river together and eventually went north to Canada. After Graham found out, he tried to go after the three enslaved musicians, but failed to recapture them.

Another example of an escape that Meyers and Walker detailed occurred when the surrounding community of abolitionists helped Lewis Williams to his freedom, with abolitionist Levi Coffin helping to plan the escape. In June of 1850, Williams managed to escape from slavery in Flemington, Kentucky. However, in October of 1853 he was caught by slave catchers near Columbus, Ohio and brought before a court after local abolitionists brought Williams’ case to attorney John Jolliffe in Cincinnati.[6] During the trial, abolitionist Levi Coffin devised a plan to help Williams escape from custody. The authors note that Coffin “arranged to temporarily replace Lewis with a man who had a similar complexion.”[7] Williams was able to sneak out through the large crowd gathered to watch the trial, and escaped out of town where he was then hidden away in the churches of Reverend William Troy, a free Black minister, and Levi Coffin, a frequent attendee at the local Congregationalist church. After hiding for a few weeks, and after a few telegrams claiming “that [Williams] had passed through the city on a train bound for Cleveland” or that he had already reached Detroit, he finally escaped northward in the back of a friendly carriage.[8]

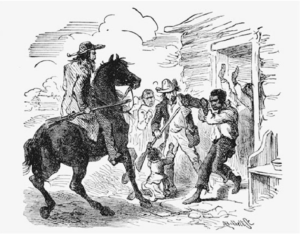

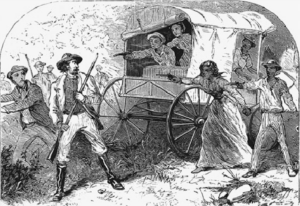

Freedom seekers in a standoff against slave catchers (Meyers and Walker)

Other notable escape tales include the stories of Matilda Lawrence, Mary Towns, and Jerry Finney. Meyers and Walker showed that when thinking of resistance to slavery, both African Americans and white abolitionists were key figures in spearheading the opposition to slavery, and often came up with clever means of escape.

Endnotes:

[1] David Meyers and Elise Meyers Walker, The Reverse Underground Railroad in Ohio (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2022), 35.

[2] Meyers and Walker, 37.

[3] Meyers and Walker, 37.

[4] Meyers and Walker, 72.

[5] Meyers and Walker, 73.

[6] Meyers and Walker, 83.

[7] Meyers and Walker, 86.

[8] Meyers and Walker, 87.