Category: Digital Storytelling Page 1 of 2

…(aka BMI-ster), Guide, Recruiter, Organizer, Political Activist, Firebrand, Military Leader, Crusader for Women’s Rights, Senator… and dead before the age of 34.

Now that is a life!

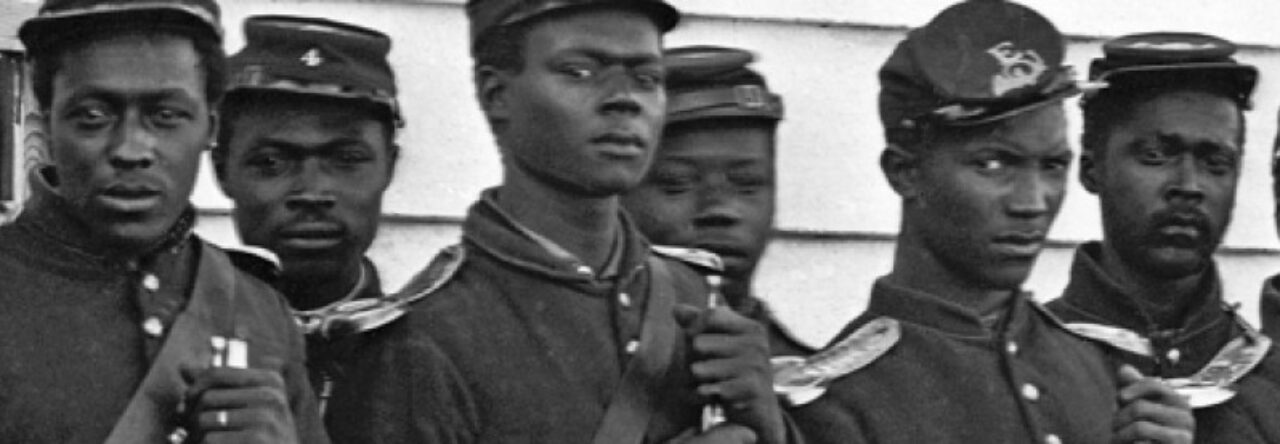

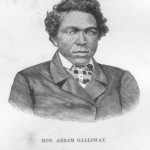

Abraham Galloway, born enslaved, freed himself and was an important figure in the Union Army during the Civil War. He was an important figure in freed and enslaved African American communities throughout his adult life. And rather than saying he worked for the Union army, it might be more accurate to say he worked with the Union army when and if it suited his needs as a leader of the African American community. (When the community was aggrieved by the actions and behaviors of the Union troops, for example, Galloway took names and kicked… but I digress.)

Illiterate, his story and his voice are hard to trace, but historian David Cecelski of North Carolina got lucky and found a trove of letters written by Mary Ann Starkey of New Bern, NC. Starkey was a close confident and fellow activist who worked with Galloway during the Civil War years.Together with his other sources, Starkey’s letters made possible Cecelski’s forthcoming book on Galloway.

I have used the information from Cecelski’s essay on Galloway in The Waterman’s Song, to make a google map of Galloway’s life. He lived large. Zoom way out right away, so that you can see the whole enchilada – North Carolina to Ontario, Ohio to Massachusetts.

I am only up to the year 1863 tonight. More tomorrow. Meanwhile, here is a preview:

In the next few years after 1963, he:

- Met with Abraham Lincoln as part of a five man delegation agitating for suffrage immediately, if not sooner

- Was elected to the North Carolina legislature as a Senator in 1868

- Worked always for the advancement of freedmen and freedwomen

- Died unexpectedly in 1870; it was estimated that 6,000 to 8,000 people attended his funeral in New Bern.*

*The population of the New Bern NC at that time was 5,000.

Galloway was the man. And then he faded from view.

Cecelski’s book on the life of Abraham Galloway, The Fire of Freedom: Abraham Galloway and the Slaves’ Civil War will be released on September 29th, 2012. ( Or you can pre-order it from Amazon, like I did, and save a few bucks.) I strongly recommend you do, too, because Galloway is a guy we are enriched by meeting.

This is the drawing of Abraham Galloway as I imagined him while I listened to David Cecelski introduce him to me, my NEH buddy Kelly Price-Steffen, (Shout out to ya, Kelly!) and the New Bedford Historical Society last summer.

This is the drawing of Abraham Galloway as I imagined him while I listened to David Cecelski introduce him to me, my NEH buddy Kelly Price-Steffen, (Shout out to ya, Kelly!) and the New Bedford Historical Society last summer.

Now I know it is not a good drawing; he defies gravity and looks like he is related to Burt Reynolds, and yet I feel it conveys the swashbuckling element I intended.

No, not Tommy Lee Jones and Johnny Cash. The Bureau of Military Information, the BMI! I am intrigued by them. Did not know anything about these sharp (no pun intended) men who were gathering intel long before the CIA made it popular.

No, not Tommy Lee Jones and Johnny Cash. The Bureau of Military Information, the BMI! I am intrigued by them. Did not know anything about these sharp (no pun intended) men who were gathering intel long before the CIA made it popular.

Figured I would find out about the BMI. First search yielded intel on how to measure my body fat. Nope. Not that BMI. I already knew from Matt’s lecture that George H. Sharpe was the lawyer/man running this stealth organization. But, then I read an excerpt on the 70 operatives employed by the BMI. I saw someone’s name, a familiar one, a person well known in Omaha, Nebraska. Grenville Dodge.

Usually known in the history textbooks as the engineer who masterminded the Transcontinental Railroad, Dodge also designed the siege of Vicksburg. But that wasn’t what caught my eye. Dodge created spy networks. Heck, he even employed two women spies, Jane Featherstone and Mary Malone. Dodge protected his well paid sleuths by always refusing to devulge their names. Well, almost always. He once yielded to U.S. Grant. It did not turn out well for the apprehended spies. Not Grant’s fault. But that’s another story.

After the Civil War, Dodge became an Iowa congressional politician and then went on to textbook railroad fame. So, why was I diverted to Dodge? Iowa borders Nebraska (where I reside) and Dodge’s house still exists for tourists (me included) to visit. Today, the main street through Omaha is Dodge Street. Nope. Not for Grenville Dodge, but for one of his relatives, Augustus Dodge.

I started looking for Men in Black and I am far from done. But, I found a Dodge instead. Not bad for an evening’s historical hunting.

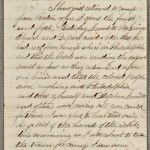

So sad listening again to the Gettysburg story of Sam Wilkeson writing beside the body of his 19 year-old son. Another 19 year-old son wrote to his father that day. Charles Douglass’s letter to his father, Frederick Douglass, reports his encounter with some Irish fellows and their differences of opinion about Meade and McClelland. (I especially like this letter because I can actually read it, unlike many letters where I have to retreat to the transcription almost at once.) Despite the racism reported and his angry, blustering reaction, I smiled reading it. He is so young… and so alive.

(His health, it turns out however, prevents him from ever serving in battle.)

Both images link to the loc page where you can view the entire letter – it is 3 pages long – or read the transcription here. (N.b. in the transcript they make mistakes, for example he is talking about Gettysburg with soldiers from Newbern N.C. – not N.Y. Why can’t I find a sound transcript? Annoying!)

My 19 year-old son is out skateboarding right now. He is not worrying about his future, or anything else. I don’t 100% appreciate his lifestyle normally – I think he should be worrying… at least a little – but today I will just go with it.

There is a story told of a visitor to the cemetery at the Old Soldier’s Home who encountered President Lincoln walking among the grave stones reciting this poem.

It has stuck with me since.

How Sleep the Brave

William Collins. 1721–1759

HOW sleep the brave, who sink to rest

By all their country’s wishes blest!

When Spring, with dewy fingers cold,

Returns to deck their hallow’d mould,

She there shall dress a sweeter sod Than Fancy’s feet have ever trod.

By fairy hands their knell is rung;

By forms unseen their dirge is sung;

There Honour comes, a pilgrim grey,

To bless the turf that wraps their clay;

And Freedom shall awhile repair

To dwell, a weeping hermit, there!

Take a teacher’s tour of Gettysburg as Matt guides you through the battle’s turning points, illustrating some of its most significant personalities and acts of heroism while sketching the bigger picture of the Gettysburg Campaign.

http://vimeo.com/48368173

http://vimeo.com/48363076

http://vimeo.com/48326791

http://vimeo.com/48326733

http://vimeo.com/48322824

I was quite impressed with Colin Macfarlane’s digital story about the black soldier Henry Spradley. It was refreshing to see this young student care about the past. He understood that finding out the story of this black soldier was important, to Colin ,Henry mattered. His gravestone had been removed and his contribution to the community,the college and his country was to be forgotten. This young man researched for hours and hours, followed clues and solved this intriging history mystery . He brought dignity back to the lost sole of Henry W. Spradley. He found a connection to the very school he was attending. Henry was a beloved custodian of Dickenson college , and a man whose funeral was so big they needed an auditorium for those whose life he had touched. thanks to Colin a whole new generation can be touched.

The idea of solving a mystery such as this would really excite my middle schoolers. I can see my students wanting to create a “movie” by using some of the rich history our town has to offer. They initially would want to be part of a movie regardless of the subject. My job is to motivate them to want to find the history and eventually love it like I do. I have been fortunate to have worked on two historical docudrama films about Kansas through Lone Chimney Films and am eager to share my knowledge with my students.

I was very impressed by the highly recommended, student film on Henry Spradley. I admire this film for two reasons. One, for the quality of the storytelling, and two, for the way in which it documents the realities and rewards of persistent research.

1. Telling a compelling story in historical context

I teach freshmen and sophomore history students in Chicago, Illinois. Each year our students, at all grade levels, are required to do a Chicago Metro History Fair project. This project takes a lot of time and effort during the first Semester, and most of the laborious work is done outside of class. In the end, students produce either a paper, exhibit, documentary, or performance. Seventy-Five percent will choose to do an exhibit and several will do papers, but only a small handful will attempt to create a documentary. Some will choose a documentary because they have experience with iMovie (or other programs). A few of them are even good at it. But where many of them struggle is making the video compelling to watch, while still being true to the historical content and overall purpose of the project.

2. The rewards of Research

Does it sound silly to say I miss my college library? I miss the feeling of having the world at my fingertips and instant access to countless databases. Research seems easy there. I think avoiding the dangers of search vs. research becomes easier with access to the right tools. I take my students to library or computer lab to show them student-friendly online databases. I harp on the jewels that can be found at local libraries, and try to set them up with a visit to the archives of the Chicago History Museum. I try to tell myself that I’m helping them “research”. I know that probably all go home and just do a simple Google “search” on their computers.

For the past few days I have been thinking ahout Catherine Clinton’s guest lecture on Harriet Tubman. In the beginning of the lecture Catherine indicated that her research proved to be challenging because Harriet Tubman didn’t leave a diary. She said much was dictated but there were minimal written records. I’ve been thinking about future historians and how they will capture our 21st century historical figures. We are innundated with communication via tweets, facebook posts, blogs & websites. Will this plethora of information make research for historians easier or more difficult?

Look at how Twitter is being used to track Obama & Romney sentiment in the upcoming presidential election. Most politicians have personal websites & use social media to connect with their consituents. I’m sure we will see lower voter turnout in the next eletion that people who actually “follow” or “like” Presidential candidates on the internet.

Finally, what is your written legacy? I know very little about my grandparents & great grandparents and often wish my ancestors left written diaries for myself and my family to read and explore. Have any of you purposefully started a blog or diary to convey personal or family history to future generations? The only thing I record are small anecdotes in cookbooks. After trying a recipe- I love to share who I made the meal for and if we liked it or not. Perhaps listening to Catherine Clinton’s assessment of how there is such minimal written information for Harriet Tubman may have sparked the same refecltion in you. What is your story and how will future generations remember you?

I’ve kept a folder on my computer for years entitled “family archives” where I’ve collected scanned news articles, obituaries, photos and census data. It’s the modern version of an old binder my father keeps of yellowed newspaper articles and handwritten notes. Back in April 2012 I think I spent a whole two days on the computer after the 1940 census data came out searching, locating, and saving every document with a family member’s name. What I haven’t done enough of is put these documents together or asked myself what kind of story they really tell. Inspired by the stories of Civil War soldiers and their families, I’ve mined several resources (family stories, the “family archives” file, local history archives through the Pittsfield Library, etc.) to tell you this personal story.

James Goggin’s (or Goggins) parents came to the United States from Macroom, County Cork, Ireland in the early 1830s. Eventually his family settled in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. It was there that he was born, raised, and eventually married Ellen Denny, probably sometime in his early 20s.

In April 1861 the Civil War began with the firing on Fort Sumter. That same month the Allen Guard organized volunteers from the hill towns of Western Massachusetts and marched to Springfield, MA to report for service.[1] James Goggins, age 24, was among them.

In April 1861 the Civil War began with the firing on Fort Sumter. That same month the Allen Guard organized volunteers from the hill towns of Western Massachusetts and marched to Springfield, MA to report for service.[1] James Goggins, age 24, was among them.

James Goggins would go on to serve two 90 day tours in the Union Army. He must have come to some injury during his first tour, since he terminated his service nearly two weeks before expiration. The cause, “disability”. What the disability was, I do not know. However, it must not have been serious since he apparently did return to the war again for a second tour of duty.

Gravestone of James “Civil War Jim” Goggins in St. Joseph Cemetary, Pittsfield, MA (Courtesy of Massachusetts Gravestone Photo Project)

James Goggins never saw battle. He never made it south of Maryland. The Allen Guard and 8th Massachusetts Regiment’s purpose in Baltimore was to protect railroad and communication lines. As a slave state, Maryland’s loyalty to the Union was questionable, particularly in those early days. Later, the 8th Regiment was sent to Annapolis and James Goggins, along with the other members of Company K, guarded the USS Constitution from “rebel mischief” [3] Family legend is that toward the end of his service he reportedly returned to Massachusetts via “Old Ironsides” when it returned to New England.

James Goggins survived the Civil War. He survived his brief “disability”. He survived the dangers of Maryland, Baltimore and Annapolis. But he did not survive to see the 1870s. He died in 1865 of lock jaw, or tetanus, in Pittsfield,MA. According to the 1870 US Census, he left behind not only his widow, Ellen Denny, but also two children: Ellen or “Nellie” (6) and James T. (4), likely born after his father’s death.

Nellie, who never married, would live to the age of 96. She was buried with her parents in 1960 (see gravestone above) James T. married and had four children of his own. Both siblings remained in Pittsfield. They must have remained close. After their mother died in 1910, Nellie lived with her brother’s family for many years (according to the 1920 and 1940 Census Records, see below).

“Civil War Jim” was my great-great-great grandfather. Most of what I knew about him before today came from stories my father told me. I knew where he was born, that he had served in the Allen Guard, rode on the Constitution, and died of lock jaw. I knew he had a son James. I wouldn’t be here if he didn’t. But before today I never knew he had a daughter, or what his wife’s name was. When I came across this image of his gravestone I was very excited, but almost immediately questioned it. My own grandparents are buried in St. Joseph Cemetery, but I’ve never seen this particular one. I knew what “Civil War Jim” died of, but I’d always imagined that he’s lived longer than 27 years.

The image I had of “Civil War Jim” in my mind was always based on a cross between what I thought a perfect Civil War soldier should be and a younger version of my grandfather (another James Goggins).

Now I feel I can put together a more intimate and realistic picture of who James Goggins was. He was 23 when he went away to war – my younger brother’s age. He left at home his young wife but no children. He must have been eager to fight since he joined immediately. Service in Maryland may have been very boring, guarding railroads and ships. I’m sure Ellen was relieved that he was away from the fighting. Was his ride on the Constitution the only time he’d been “at sea”? He barely ever knew his children. He might not have even known he would have a son when he died. Ellen was lucky enough to see her husband come home from the war but at age 24 (the age I am now) she was a widow with two young children. How different was her pain and loneliness compared to women like Anne Colwell?

[1] George Warren Nason, History and Complete Roster of the Massachusetts Regiments; Minute Men of ’61 [Boston, 1910]

[2] Record of the Massachusetts Volunteers 1861-1865. Volume 1. [Adjunct General, Boston: 1868]

[3] Christopher Marcisz, “When the Civil War Began in the Berkshires”. April 11, 2011. Times Union. [http://blog.timesunion.com/berkshires/when-the-civil-war-began-for-the-berkshires/1247/]