No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war.

No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war.

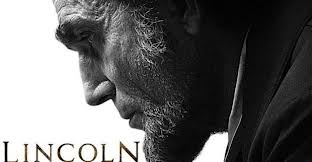

Yet this deficit of evidence also provides “Lincoln” scriptwriter Tony Kushner, director Steven Spielberg and actors such as Daniel Day-Lewis and Sally Field with freedom to offer their own interpretations. They can imagine private moments where historians are otherwise forced to remain silent or least circumspect. Two good examples of this occur in the film during Scenes 29 and 30 where President Lincoln engages in loud, back-to-back arguments with his oldest son Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and then with his wife Mary. In one episode outside a temporary wartime hospital, the president actually slaps his son in anger. This is wholly invented. There is no source for this scene, and it seems entirely implausible to most Lincoln historians, not only because both Lincolns were almost notorious as parents for not disciplining their children, but also because Robert had a reputation for being so outwardly respectful toward his parents. It seems almost impossible to believe that eldest Lincoln son would have told his father, as he does in the movie, “It’s mama you’re scared of, not me getting killed” and that his father would have then lost control and slapped him in public. And yet … it could have happened. There were tensions between father and son, and there was a quiet debate over whether or not Robert should join the Union army. Nonetheless, this is a risky use of artistic license disconnected from any serious evidence.

The second major argument depicted in the movie is more plausible, but also wholly invented. The script has Mary Lincoln telling her husband that “you’ve always blamed Robert for being born, for trapping you in a marriage that’s only ever given you grief and caused you regret!” The line implies that the Lincoln’s had a shotgun wedding of some sort, but Robert was born almost exactly nine months after their wedding day in the early 1840s. Nor is there any contemporary evidence that Mary Lincoln refused to console their youngest son Tad after his older brother Willie died, or that the president ever threatened her that “for everybody’s goddamned sake, I should have clapped you in the madhouse!” Some of that information (about the “madhouse”) derives from Elizabeth Keckley’s recollected accounts about Mary’s grief in 1862, but most of the vitriol in this exchange is imagined –again, possibly real but certainly not proven by any reliable record.

Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in early December 1864. There is no record of Elizabeth Keckley ever attending theater or opera with the Lincolns and it seems unlikely that she would have remained in the box with the presidential couple while they conversed. Yet Scene 31 has Keckley overhearing how Mary Lincoln finally reconciled herself to the decision about her son’s enlistment. She informs her husband crisply, “I believe you when you insist that amending the constitution and abolishing slavery will end this war. And since you are sending my son into the war, woe unto you if you fail to pass the amendment.” Lincoln at first demurs, claiming, “Seward doesn’t want me leaving big muddy footprints all over town.” But Mary Lincoln is unyielding. ”Seward can’t do it,” she claims. ”You must. Because if you fail to secure the necessary votes, woe unto you, sir. You will answer to me.”

Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in early December 1864. There is no record of Elizabeth Keckley ever attending theater or opera with the Lincolns and it seems unlikely that she would have remained in the box with the presidential couple while they conversed. Yet Scene 31 has Keckley overhearing how Mary Lincoln finally reconciled herself to the decision about her son’s enlistment. She informs her husband crisply, “I believe you when you insist that amending the constitution and abolishing slavery will end this war. And since you are sending my son into the war, woe unto you if you fail to pass the amendment.” Lincoln at first demurs, claiming, “Seward doesn’t want me leaving big muddy footprints all over town.” But Mary Lincoln is unyielding. ”Seward can’t do it,” she claims. ”You must. Because if you fail to secure the necessary votes, woe unto you, sir. You will answer to me.”

(This post has been excerpted from a longer essay, “Warning: Artists at Work,” that appears in “The Unofficial Guide to Spielberg’s Lincoln” which is part of the House Divided Project’s new Emancipation Digital Classroom).

In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.

In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.  Smith

Smith Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities.

Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities.  The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that

The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that  Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.

Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.